Sarah Wentworth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Sarah Morton Cox 1805 Sydney, Australia |

| Died | 1880 (aged 74–75) England |

| Resting place | Ocklynge Cemetery, Eastbourne, Sussex |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 10 |

Sarah Morton Wentworth (née Cox; 1805–1880) was an Australian currency lass and apprentice. She brought the first breach of promise suit in Australia, during which she was represented by barrister and statesman William Wentworth, her future husband.

Life

Sarah Cox was born in 1805 to convict parents Frances Morton and Francis Cox, the latter a blacksmith. Her parents had completed their sentences by the time of her birth. Francis Cox and Morton never married as the former had a family in England. They lived in Sydney Cove.[1]

By the time of Payne's marriage proposal, Cox was living at the home of a Mrs. Foster, a milliner for whom she worked as an apprentice. She would later work at a butcher's shop set up by her partner William Wentworth.[2]

Breach of promise suit

In 1825, Cox brought a breach of promise lawsuit against Captain John Payne, who had withdrawn his marriage proposal. Hers was the first breach of promise case to be tried in Australia. She was represented by barrister and statesman William Wentworth. Payne, who vowed to Cox "that his eyes might drop out of his head if he did not fulfil his promise of marriage," cheated on her with a wealthier widow by the name of Mrs. Leverton, following which Cox sent him a volley of invective-filled letters. Payne was found guilty and ordered to pay £100 in damages.[1][3]

Relationship with William Wentworth

Cox and Wentworth became romantically involved whilst she was being represented by him. That year, Wentworth began leasing the 295-acre Petersham Estate and from mid 1825 the two lived there together. In 1825, Cox and Wentworth named their first daughter Thomasine in honour of Sir Thomas Brisbane, former Governor of New South Wales (Thomasine was born only 6 months after her court case against Payne). Cox and Wentworth moved into Vaucluse House a few years later, where Cox lived a comfortable but secluded life.[2][1]

On 26 October 1829 at St Philip's Church Hill, Sydney, Cox married William Wentworth.[1] Three days prior to their marriage, a love poem to Sarah authored by William appeared in The Australian:

- For I must love thee, love thee on,

- Till life's remotest latest minute;

- And when the light of life is gone,—

- Thou'll find its lamp—had thee within it.[2]

William Wentworth would in 1830 father a child out of wedlock with Jamima Eagar, the estranged wife of Edward Eagar.[2]

Carol Liston, biographer of Sarah Wentworth, noted that her commissioning of various domestic duties was fundamental to William Wentworth's and their children's success.[1]

Societal treatment

Wentworth was long ill-treated owing to her convict heritage and the circumstances of her involvement with William Wentworth.[1] Finally, however, she was accepted by high society. She became acquainted with the Sir John Young and Lady Young whilst Sir Young was Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands on Corfu whilst the Wentworths were in Europe. Upon returning to Sydney, she was regularly invited to Government House. She wrote that "all the nice families ... call on us." A ball was held for the Wentworth family at Roslyn Hall in modern-day Kings Cross in September 1862 featuring the Vice-Regal couple and other distinguished guests, by which point only Sarah Wentworth's son-in-low Thomas Fisher looked down upon the family.[2]

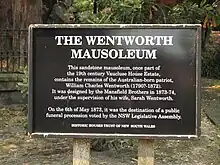

Wentworth Mausoleum

Sarah Wentworth was instrumental in the design of the heritage-listed Wentworth Mausoleum. The vault, according to newspaper descriptions, was constructed as Sarah had desired, and she commissioned the chapel built above it.[4]

As early as 1831, following the death of Sarah Wentworth's father Francis Cox, William Wentworth intended to have land consecrated and to build a family vault at Vaucluse. This did not eventuate in his lifetime but Wentworth had informed his family that he wished to be buried near a rocky outcrop on the hill above Parsley Bay. The site was visible from the front verandah of the house and overlooked both the harbour and the estate.[4]

After William Wentworth's death at the family's rented estate, Merly House, near Wimborne, Dorset, England in March 1872, Sarah Wentworth sent her son-in-law Thomas Fisher a sketch of the location and instructions that a vault was to be hewn out of a large single rock on the slope but "left in its natural state outside". Sarah informed Fisher that she would travel to Brussels to order marble for the vault and would also bring "some Iron gates and railing to enclose it". The vault was to be large - Eliza wrote: 'it was Papa's wish to have my grandfather, my Uncle & Willie & Bell & poor Nellie & we should all like to be there when our time comes.[4]

Sarah accepted the New South Wales Government's proposal to accord her husband the honours of a public funeral. The funeral service for William Charles Wentworth was held at St Andrew's Cathedral, Sydney, on 6 May 1873. The only women admitted to the congregation of 2,000 were female members of Wentworth's family.[4]

Sarah commissioned the architects Mansfield Brothers to design a chapel to be constructed over the vault. The chapel's Gothic Revival design seemingly was intended to complement the Vaucluse estate's other Gothic style buildings. By November 1873 the chapel was still incomplete: "Men are working, but as Miss W said they are drunk and away oftener than at work". The stone and iron palisade fence was erected by early March 1874.[4]

The brass plaque commemorating Sarah Eleanor may have been responsible for the long-held belief that her mother, Sarah Wentworth, was buried in the mausoleum. Despite her desire for the family to "all rest together in our native place", Sarah was buried in July 1880 in Ocklynge Cemetery at Eastbourne, Sussex.[4]

Family

Andrew Tink notes that Wentworth relied on "persuasion rather than force" in getting her children to act.[2] The Wentworths had seven daughters and three sons:

- Thomasine Wentworth (1825–1913)

- William Charles Wentworth (1827–1859)

- Fanny Katherine Wentworth (1829–1893)

- Fitzwilliam Wentworth (1833–1915) married Mary Jane Hill, daughter of George Hill

- William Charles Wentworth III (1871–1949) married Florence Denise Griffiths, daughter of George Neville Griffiths

- William Charles Wentworth IV (1907–2003) (known as Bill Wentworth, Liberal member of Parliament 1949–77, inaugural Minister in charge of Aboriginal Affairs under the Prime Minister)

- Diana Wentworth Wentworth married Mungo Ballardie MacCallum (1913–99)

- Mungo Wentworth MacCallum (1941–2020)

- William Charles Wentworth III (1871–1949) married Florence Denise Griffiths, daughter of George Neville Griffiths

- Sarah Eleanor Wentworth (1835–1857)

- Eliza Sophia Wentworth (1838–1898)

- Isabella Christiana (Christina) Wentworth (1840–1856)

- Laura Wentworth (1842–1887) married Henry William Keays-Young in 1872.

- Edith Wentworth (1845–1891) married Rev. Sir Charles Gordon-Cumming-Dunbar, 9th Baronet in 1872.

- D'Arcy Bland Wentworth (1848–1922).

Legacy

Writing about her lawsuit, Alecia Simmons in The Sydney Morning Herald in 2008 described then-Sarah Cox as "a fiercely independent 18-year-old".[3] She was nineteen at the time.[1]

A biography was written about Sarah Wentworth by Carol Listen in 1988. Referencing this, Grace Carroll writes:

Although William Charles Wentworth continues to be heralded as a significant figure in Australian history, Sarah's story has not been forgotten. Liston's 1988 biography, Sarah Wentworth: Mistress of Vaucluse, made a significant contribution to revealing Sarah's prominent position in her family and home, suggesting that she may well have been the strong and refined woman represented in Simonetti's bust. As a result, visitors to Vaucluse House today learn of the woman who played a vital role in establishing the House and the Wentworth family legacy. Her story brings to life the lot of a colonial woman whose experiences were both extraordinary, yet representative of that of many 'currency lasses.'[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Carroll, Grace (8 December 2015). "The Wentworths – Hidden in Plain Sight". Portrait magazine. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Tink, Andrew (2009). William Charles Wentworth : Australia's greatest native son. Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-192-5.

- 1 2 Simmonds, Alecia (21 June 2008). "For same-sex couples, the law must embrace love". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 17 September 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Wentworth Mausoleum and site". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Department of Planning & Environment. H00622. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.

Text is licensed by State of New South Wales (Department of Planning and Environment) under CC-BY 4.0 licence.