| First Sasun Resistance | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Location of the 1894 and 1904 Sasun uprisings | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Hunchak Party | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

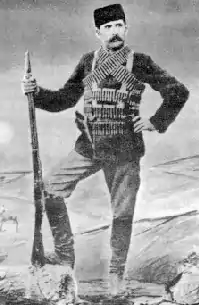

Mihran Damadian Hampartsoum Boyadjian Hrayr Dzhoghk | Abdul Hamid II | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 8,000[1] | 10,000[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 20,000 rebel and civilians[1] | 550[1] | ||||||

The Sasun rebellion of 1894, also known as the First Sasun resistance (Armenian: Սասնո առաջին ապստամբութիւն), was the conflict between Ottoman Empire's Hamidiye forces and the Armenian fedayi belonging to the Armenian national movement's Hunchakian party in the Sasun region.

Background

The Social Democrat Hunchakian Party was an Armenian national movement active in the region. In 1894, Sultan Abdul Hamid II began to target the Armenian people in a precursor of the Hamidian massacres. This persecution strengthened devolution sentiment among Armenians.[2][3]

In Sasun Armenians were organized by Hunchak activists, such as Mihran Damadian, Hampartsoum Boyadjian (Medzn Mourad) and Hrayr Dzhoghk.

In his unpublished memoir, the missionary Royal M. Cole, who was based in Bitlis, recounted how Tahsin Paşa used a general atmosphere of suspicion to exaggerate the situation in the mountains and secure an imperial order for the destruction that occurred in late summer of 1894. Cole suggested that if Tahsin and the Ottoman State had bothered to investigate, they might have found only a small number of well-armed Armenians desperate to organize self-defense bands among the mountaineers. When Zeki Paşa, the commander of the Fourth Army stationed in Erzincan, arrived in Sasun in early September, he strongly criticized Tahsin Paşa for overstating the threat posed by the Sasun mountaineers to the Ottoman government. According to Cole, Zeki Paşa fiercely attacked Tahsin Paşa for calling up so many troops and causing such a massacre on such a flimsy pretext. Zeki Paşa believed that the poor and weak-looking Armenians he saw were not a real threat to the government, and he criticized Tahsin Paşa for leaving without facing him.[4]

Conflict

Sasun was the location for the first notable battle in the Armenian resistance movement. The Armenians of Sasun confronted the Ottoman army and Kurdish irregulars at Sasun, succumbing to superior numbers.[5]

Foreign news agents protested vehemently against the Sasun even.; British prime minister William Ewart Gladstone called Hamid "the Great Criminal" or "the Red Sultan". The rest of the Great Powers also protested and demanded the execution of Ottoman Sultan Hamid's promised reforms. An investigation committee composed of French, British, and Russian representatives were sent to the region in order to examine the event.[5]

Aftermath

In May 1895, the aforementioned foreign powers prepared a set of reforms. However, they were never carried out, because they were not actively imposed on the Ottoman Empire. The Russian Empire's policies vis-à-vis the Armenian question had changed. In fact, the Russian foreign minister Alexei Lobanov-Rostovsky supported Ottoman integrity. Moreover, he was so anti-Armenian that he wanted an "Armenia without Armenians". On the other hand, Britain had gained considerable influence and power in former Ottoman Egypt and Cyprus, and for Gladstone, good relations with the Ottomans were less important than before. Meanwhile, the Ottomans had found a new European ally, Germany's Bismarck. The Ottoman Empire thus felt free to commit further massacres, in 1896.[5]

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 A Crime of Silence: The Armenian Genocide , p 133

- ↑ "The Rise of Nationalism and the Collapse of the Ottoman Empire". Archived from the original on 2020-10-30.

- ↑ Ter Minassian, Anahide (2012). Nationalism and Socialism in the Armenian Revolutionary Movement (1887-1912). İletişim Yayınları.

- ↑ Miller, Owen. Rethinking the Violence in the Sasun Mountains (1893-1894. p. 31.

- 1 2 3 Kurdoghlian, Mihran (1996). Hayots Badmoutioun, Volume III (in Armenian). Athens, Greece: Hradaragoutioun Azkayin Ousoumnagan Khorhourti. pp. 42–44.