| B-2 Spirit | |

|---|---|

| |

| A U.S. Air Force B-2 Spirit flying over the Pacific Ocean in 2016 | |

| Role | Stealth strategic heavy bomber |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Northrop Corporation Northrop Grumman |

| First flight | 17 July 1989 |

| Introduction | 1 January 1997 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Produced | 1987–2000 |

| Number built | 21[1][2] |

The Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit, also known as the Stealth Bomber, is an American heavy strategic bomber, featuring low-observable stealth technology designed to penetrate dense anti-aircraft defenses. A subsonic flying wing with a crew of two, the plane was designed by Northrop (later Northrop Grumman) and produced from 1987 to 2000.[1][3] The bomber can drop conventional and thermonuclear weapons,[4] such as up to eighty 500-pound class (230 kg) Mk 82 JDAM GPS-guided bombs, or sixteen 2,400-pound (1,100 kg) B83 nuclear bombs. The B-2 is the only acknowledged in-service aircraft that can carry large air-to-surface standoff weapons in a stealth configuration.

Development began under the Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) project during the Carter administration, which cancelled the Mach 2-capable B-1A bomber in part because the ATB showed such promise. But development difficulties delayed progress and drove up costs. Ultimately, the program produced 21 B-2s at an average cost of $2.13 billion ((~$3.88 billion in 2022), including development, engineering, testing, production, and procurement.[5] Building each aircraft cost an average of US$737 million,[5] while total procurement costs (including production, spare parts, equipment, retrofitting, and software support) averaged $929 million (~$1.07 billion in 2022) per plane.[5]

The project's considerable capital and operating costs made it controversial in the U.S. Congress even before the winding down of the Cold War dramatically reduced the desire for a stealth aircraft designed to strike deep in Soviet territory. Consequently, in the late 1980s and 1990s lawmakers shrank the planned purchase of 132 bombers to 21.

As of 2015, twenty B-2s were in service with the United States Air Force,[4] one having been destroyed in a 2008 crash.[6] The Air Force plans to operate them until 2032, when the Northrop Grumman B-21 Raider is to replace them.[7]

The B-2 can perform attack missions at altitudes of up to 50,000 feet (15,000 m); it has an unrefueled range of more than 6,000 nautical miles (6,900 mi; 11,000 km) and can fly more than 10,000 nautical miles (12,000 mi; 19,000 km) with one midair refueling. It entered service in 1997 as the second aircraft designed with advanced stealth technology, after the Lockheed F-117 Nighthawk attack aircraft. Primarily designed as a nuclear bomber, the B-2 was first used in combat to drop conventional, non-nuclear ordnance in the Kosovo War in 1999. It was later used in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya.[8]

Development

Origins

By the mid-1970s, military aircraft designers had learned of a new method to avoid missiles and interceptors, known today as "stealth". The concept was to build an aircraft with an airframe that deflected or absorbed radar signals so that little was reflected back to the radar unit. An aircraft having radar stealth characteristics would be able to fly nearly undetected and could be attacked only by weapons and systems not relying on radar. Although other detection measures existed, such as human observation, infrared scanners, as well as acoustic locators, their relatively short detection range or poorly-developed technology allowed most aircraft to fly undetected, or at least untracked, especially at night.[9]

In 1974, DARPA requested information from U.S. aviation firms about the largest radar cross-section of an aircraft that would remain effectively invisible to radars.[10] Initially, Northrop and McDonnell Douglas were selected for further development. Lockheed had experience in this field with the development of the Lockheed A-12 and SR-71, which included several stealthy features, notably its canted vertical stabilizers, the use of composite materials in key locations, and the overall surface finish in radar-absorbing paint. A key improvement was the introduction of computer models used to predict the radar reflections from flat surfaces where collected data drove the design of a "faceted" aircraft. Development of the first such designs started in 1975 with the Have Blue, a model Lockheed built to test the concept.[11]

Plans were well advanced by the summer of 1975, when DARPA started the Experimental Survivability Testbed project. Northrop and Lockheed were awarded contracts in the first round of testing. Lockheed received the sole award for the second test round in April 1976 leading to the Have Blue program and eventually the F-117 stealth attack aircraft.[12] Northrop also had a classified technology demonstration aircraft, the Tacit Blue in development in 1979 at Area 51. It developed stealth technology, LO (low observables), fly-by-wire, curved surfaces, composite materials, electronic intelligence, and Battlefield Surveillance Aircraft Experimental. The stealth technology developed from the program was later incorporated into other operational aircraft designs, including the B-2 stealth bomber.[13]

ATB program

By 1976, these programs had progressed to a position in which a long-range strategic stealth bomber appeared viable. President Jimmy Carter became aware of these developments during 1977, and it appears to have been one of the major reasons the B-1 was canceled.[14] Further studies were ordered in early 1978, by which point the Have Blue platform had flown and proven the concepts. During the 1980 presidential election campaign in 1979, Ronald Reagan repeatedly stated that Carter was weak on defense and used the B-1 as a prime example. In response, on 22 August 1980 the Carter administration publicly disclosed that the United States Department of Defense was working to develop stealth aircraft, including a bomber.[15]

The Advanced Technology Bomber (ATB) program began in 1979.[16] Full development of the black project followed, funded under the code name "Aurora".[17] After the evaluations of the companies' proposals, the ATB competition was narrowed to the Northrop/Boeing and Lockheed/Rockwell teams with each receiving a study contract for further work.[16] Both teams used flying wing designs.[17] The Northrop proposal was code named "Senior Ice", and the Lockheed proposal code named "Senior Peg".[18] Northrop had prior experience developing the YB-35 and YB-49 flying wing aircraft.[19] The Northrop design was larger while the Lockheed design included a small tail.[17] In 1979, designer Hal Markarian produced a sketch of the aircraft that bore considerable similarities to the final design.[20] The USAF originally planned to procure 165 ATB bombers.[1]

The Northrop team's ATB design was selected over the Lockheed/Rockwell design on 20 October 1981.[16][21] The Northrop design received the designation B-2 and the name "Spirit". The bomber's design was changed in the mid-1980s when the mission profile was changed from high-altitude to low-altitude, terrain-following. The redesign delayed the B-2's first flight by two years and added about US$1 billion to the program's cost.[15] An estimated US$23 billion was secretly spent for research and development on the B-2 by 1989.[22] MIT engineers and scientists helped assess the mission effectiveness of the aircraft under a five-year classified contract during the 1980s.[23] Northrop was the B-2's prime contractor; major subcontractors included Boeing, Hughes Aircraft (now Raytheon), GE, and Vought Aircraft.[8]

Secrecy and espionage

During its design and development, the Northrop B-2 program was a black project; all program personnel needed a secret clearance.[24] Still, it was less closely held than the Lockheed F-117 program; more people in the federal government knew about the B-2, and more information about the project was available. Both during development and in service, considerable effort has been devoted to maintaining the security of the B-2's design and technologies. Staff working on the B-2 in most, if not all, capacities need a level of special-access clearance and undergo extensive background checks carried out by a special branch of the USAF.[25]

A former Ford automobile assembly plant in Pico Rivera, California, was acquired and heavily rebuilt; the plant's employees were sworn to secrecy. To avoid suspicion, components were typically purchased through front companies, military officials would visit out of uniform, and staff members were routinely subjected to polygraph examinations. Nearly all information on the program was kept from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and members of Congress until the mid-1980s.[26]

The B-2 was first publicly displayed on 22 November 1988 at United States Air Force Plant 42 in Palmdale, California, where it was assembled. This viewing was heavily restricted, and guests were not allowed to see the rear of the B-2. However, Aviation Week editors found that there were no airspace restrictions above the presentation area and took aerial photographs of the aircraft's secret rear section[27] with suppressed engine exhausts.[28] The B-2's (s/n 82-1066 / AV-1) first public flight was on 17 July 1989 from Palmdale to Edwards Air Force Base.[27]

In 1984, Northrop employee Thomas Patrick Cavanagh was arrested for attempting to sell classified information from the Pico Rivera factory to the Soviet Union.[29] Cavanagh was sentenced to life in prison in 1985 but released on parole in 2001.[30] In October 2005, Noshir Gowadia, a design engineer who worked on the B-2's propulsion system, was arrested for selling classified information to China.[31] Gowadia was convicted and sentenced to 32 years in prison.[32]

Program costs and procurement

A procurement of 132 aircraft was planned in the mid-1980s but was later reduced to 75.[33] By the early 1990s the Soviet Union dissolved, effectively eliminating the Spirit's primary Cold War mission. Under budgetary pressures and Congressional opposition, in his 1992 State of the Union address, President George H. W. Bush announced B-2 production would be limited to 20 aircraft.[34] In 1996, however, the Clinton administration, though originally committed to ending production of the bombers at 20 aircraft, authorized the conversion of a 21st bomber, a prototype test model, to Block 30 fully operational status at a cost of nearly $500 million (~$866 million in 2022).[35] In 1995, Northrop made a proposal to the USAF to build 20 additional aircraft with a flyaway cost of $566 million each.[36]

The program was the subject of public controversy for its cost to American taxpayers. In 1996, the GAO disclosed that the USAF's B-2 bombers "will be, by far, the most costly bombers to operate on a per aircraft basis", costing over three times as much as the B-1B (US$9.6 million annually) and over four times as much as the B-52H (US$6.8 million annually). In September 1997, each hour of B-2 flight necessitated 119 hours of maintenance. Comparable maintenance needs for the B-52 and the B-1B are 53 and 60 hours, respectively, for each hour of flight. A key reason for this cost is the provision of air-conditioned hangars large enough for the bomber's 172 ft (52 m) wingspan, which are needed to maintain the aircraft's stealth properties, particularly its "low-observable" stealth skins.[37][38] Maintenance costs are about $3.4 million per month for each aircraft.[39] An August 1995 GAO report disclosed that the B-2 had trouble operating in heavy rain, as rain could damage the aircraft's stealth coating, causing procurement delays until an adequate protective coating could be found. In addition, the B-2's terrain-following/terrain-avoidance radar had difficulty distinguishing rain from other obstacles, rendering the subsystem inoperable during rain.[40] However a subsequent report in October 1996 noted that the USAF had made some progress in resolving the issues with the radar via software fixes and hoped to have these fixes undergoing tests by the spring of 1997.[41]

The total "military construction" cost related to the program was projected to be US$553.6 million in 1997 dollars. The cost to procure each B-2 was US$737 million in 1997 dollars (equivalent to US$1254 million in 2021[42]), based only on a fleet cost of US$15.48 billion.[5] The procurement cost per aircraft, as detailed in GAO reports, which include spare parts and software support, was $929 million per aircraft in 1997 dollars.[5]

The total program cost projected through 2004 was US$44.75 billion in 1997 dollars (equivalent to US$76 billion in 2021[42]). This includes development, procurement, facilities, construction, and spare parts. The total program cost averaged US$2.13 billion per aircraft.[5] The B-2 may cost up to $135,000 per flight hour to operate in 2010, which is about twice that of the B-52 and B-1.[43][44]

Opposition

In its consideration of the fiscal year 1990 defense budget, the House Armed Services Committee trimmed $800 million from the B-2 research and development budget, while at the same time staving off a motion to end the project. Opposition in committee and in Congress was mostly broad and bipartisan, with Congressmen Ron Dellums (D-CA), John Kasich (R-OH), and John G. Rowland (R-CT) authorizing the motion to end the project—as well as others in the Senate, including Jim Exon (D-NE) and John McCain (R-AZ) also opposing the project.[45] Dellums and Kasich, in particular, worked together from 1989 through the early 1990s to limit production to 21 aircraft and were ultimately successful.[46]

The escalating cost of the B-2 program and evidence of flaws in the aircraft's ability to elude detection by radar[45] were among factors that drove opposition to continue the program. At the peak production period specified in 1989, the schedule called for spending US$7 billion to $8 billion per year in 1989 dollars, something Committee Chair Les Aspin (D-WI) said "won't fly financially".[47] In 1990, the Department of Defense accused Northrop of using faulty components in the flight control system; it was also found that redesign work was required to reduce the risk of damage to engine fan blades by bird ingestion.[48]

In time, several prominent members of Congress began to oppose the program's expansion, including Senator John Kerry (D-MA), who cast votes against the B-2 in 1989, 1991, and 1992. By 1992, Bush had called for the cancellation of the B-2 and promised to cut military spending by 30% in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union.[49] In October 1995, former Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force, General Mike Ryan, and former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General John Shalikashvili, strongly recommended against Congressional action to fund the purchase of any additional B-2s, arguing that to do so would require unacceptable cuts in existing conventional and nuclear-capable aircraft,[50] and that the military had greater priorities in spending a limited budget.[51]

Some B-2 advocates argued that procuring twenty additional aircraft would save money because B-2s would be able to deeply penetrate anti-aircraft defenses and use low-cost, short-range attack weapons rather than expensive standoff weapons. However, in 1995, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and its Director of National Security Analysis found that additional B-2s would reduce the cost of expended munitions by less than US$2 billion in 1995 dollars during the first two weeks of a conflict, in which the USAF predicted bombers would make their greatest contribution; this was a small fraction of the US$26.8 billion (in 1995 dollars) life cycle cost that the CBO projected for an additional 20 B-2s.[52]

In 1997, as Ranking Member of the House Armed Services Committee and National Security Committee, Congressman Ron Dellums (D-CA), a long-time opponent of the bomber, cited five independent studies and offered an amendment to that year's defense authorization bill to cap production of the bombers to the existing 21 aircraft; the amendment was narrowly defeated.[53] Nonetheless, Congress did not approve funding for additional B-2s.

Further developments

Several upgrade packages have been applied to the B-2. In July 2008, the B-2's onboard computing architecture was extensively redesigned; it now incorporates a new integrated processing unit that communicates with systems throughout the aircraft via a newly installed fiber optic network; a new version of the operational flight program software was also developed, with legacy code converted from the JOVIAL programming language to standard C.[54][55] Updates were also made to the weapon control systems to enable strikes upon moving targets, such as ground vehicles.[56]

On 29 December 2008, USAF officials awarded a US$468 million contract to Northrop Grumman to modernize the B-2 fleet's radars.[57] Changing the radar's frequency was required as the United States Department of Commerce had sold that radio spectrum to another operator.[58] In July 2009, it was reported that the B-2 had successfully passed a major USAF audit.[59] In 2010, it was made public that the Air Force Research Laboratory had developed a new material to be used on the part of the wing trailing edge subject to engine exhaust, replacing existing material that quickly degraded.[60]

In July 2010, political analyst Rebecca Grant speculated that when the B-2 becomes unable to reliably penetrate enemy defenses, the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II may take on its strike/interdiction mission, carrying B61 nuclear bombs as a tactical bomber.[61] However, in March 2012, The Pentagon announced that a $2 billion, 10-year-long modernization of the B-2 fleet was to begin. The main area of improvement would be replacement of outdated avionics and equipment.[62] Continued modernization efforts likely have continued in secret, as alluded to by a B-2 commander from Whiteman Air Force Base in April 2021, possibly indicating offensive weapons capability against threatening air defenses and aircraft. He stated:

without getting into specifics, and without getting into things that we frankly just don't discuss in open channels, I will tell you that our current bomber fleet, and this is all of them, we use some pretty innovative ways to integrate modern weapons capabilities to have us both maintain and increase our survivability. And for the B-2 specifically, the expansion of some of our strike capabilities allow us to increase our survivability beyond the fighter escort realm. Now the B-2 fleet is continuing to do that technological advancement, and that's enabled us to expand our strike capabilities, as well. Although we've been around for over 30 years there's a lot of life left in this platform and up until the B-21 as well on the scene and doing its job, this aircraft will continue to be at the forefront of our country and our nation's defense... and with these, and continued innovative upgrades, and weapons system capabilities we will continue to do that until the last jet flies off the ramp into retirement.[63]

It was reported in 2011 that The Pentagon was evaluating an unmanned stealth bomber, characterized as a "mini-B-2", as a potential replacement in the near future.[64] In 2012, USAF Chief of Staff General Norton Schwartz stated the B-2's 1980s-era stealth technologies would make it less survivable in future contested airspaces, so the USAF is to proceed with the Next-Generation Bomber despite overall budget cuts.[65] In 2012 projections, it was estimated that the Next-Generation Bomber would have an overall cost of $55 billion.[66]

In 2013, the USAF contracted for the Defensive Management System Modernization program to replace the antenna system and other electronics to increase the B-2's frequency awareness.[67] The Common Very Low Frequency Receiver upgrade allows the B-2s to use the same very low frequency transmissions as the Ohio-class submarines so as to continue in the nuclear mission until the Mobile User Objective System is fielded. In 2014, the USAF outlined a series of upgrades including nuclear warfighting, a new integrated processing unit, the ability to carry cruise missiles, and threat warning improvements.[68]

In 1998, a Congressional panel advised the USAF to refocus resources away from continued B-2 production and instead begin development of a new bomber, either a new build or a variant of the B-2. In its 1999 bomber roadmap the USAF eschewed the panel's recommendations, believing its current bomber fleet could be maintained until the 2030s. The service believed that development could begin in 2013, in time to replace aging B-2s, B-1s and B-52s around 2037.[69][70]

Although the USAF previously planned to operate the B-2 until 2058, the FY 2019 budget moved up its retirement to "no later than 2032". It also moved the retirement of the B-1 to 2036 while extending the B-52's service life into the 2050s, because the B-52 has lower maintenance costs, versatile conventional payload, and the ability to carry nuclear cruise missiles (which the B-1 is treaty-prohibited from doing). The decision to retire the B-2 early was made because the small fleet of 20 is considered too expensive per plane to retain, with its position as a stealth bomber being taken over with the introduction of the B-21 Raider starting in the mid-2020s.[7]

Design

Overview

The B-2 Spirit was developed to take over the USAF's vital penetration missions, allowing it to travel deep into enemy territory to deploy ordnance, which could include nuclear weapons.[71] The B-2 is a flying wing aircraft, meaning that it has no fuselage or tail.[71] It has significant advantages over previous bombers due to its blend of low-observable technologies with high aerodynamic efficiency and a large payload. Low observability provides greater freedom of action at high altitudes, thus increasing both range and field of view for onboard sensors. The USAF reports its range as approximately 6,000 nautical miles (6,900 mi; 11,000 km).[8][72] At cruising altitude, the B-2 refuels every six hours, taking on up to 50 short tons (45,000 kg) of fuel at a time.[73]

The development and construction of the B-2 required pioneering use of computer-aided design and manufacturing technologies due to its complex flight characteristics and design requirements to maintain very low visibility to multiple means of detection.[71][74] The B-2 bears a resemblance to earlier Northrop aircraft; the YB-35 and YB-49 were both flying wing bombers that had been canceled in development in the early 1950s,[75] allegedly for political reasons.[76] The resemblance goes as far as B-2 and YB-49 having the same wingspan.[77][78] The YB-49 also had a small radar cross-section.[79][80]

Approximately 80 pilots fly the B-2.[73] Each aircraft has a crew of two, a pilot in the left seat and mission commander in the right,[8] and has provisions for a third crew member if needed.[81] For comparison, the B-1B has a crew of four and the B-52 has a crew of five.[8] The B-2 is highly automated, and one crew member can sleep in a camp bed, use a toilet, or prepare a hot meal while the other monitors the aircraft, unlike most two-seat aircraft. Extensive sleep cycle and fatigue research was conducted to improve crew performance on long sorties.[73][82][83] Advanced training is conducted at the USAF Weapons School.[84]

Armaments and equipment

In the envisaged Cold War scenario, the B-2 was to perform deep-penetrating nuclear strike missions, making use of its stealthy capabilities to avoid detection and interception throughout the missions.[85] There are two internal bomb bays in which munitions are stored either on a rotary launcher or two bomb-racks; the carriage of the weapons loadouts internally results in less radar visibility than external mounting of munitions.[86][87] The B-2 is capable of carrying 40,000 lb (18,000 kg) of ordnance.[8] Nuclear ordnance includes the B61 and B83 nuclear bombs; the AGM-129 ACM cruise missile was also intended for use on the B-2 platform.[87][88]

In light of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it was decided to equip the B-2 for conventional precision attacks as well as for the strategic role of nuclear-strike.[85][89] The B-2 features a sophisticated GPS-Aided Targeting System (GATS) that uses the aircraft's APQ-181 synthetic aperture radar to map out targets prior to the deployment of GPS-aided bombs (GAMs), later superseded by the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM). In the B-2's original configuration, up to 16 GAMs or JDAMs could be deployed;[90] An upgrade program in 2004 raised the maximum carrier capacity to 80 JDAMs.[91]

The B-2 has various conventional weapons in its arsenal, including Mark 82 and Mark 84 bombs, CBU-87 Combined Effects Munitions, GATOR mines, and the CBU-97 Sensor Fuzed Weapon.[92] In July 2009, Northrop Grumman reported the B-2 was compatible with the equipment necessary to deploy the 30,000 lb (14,000 kg) Massive Ordnance Penetrator (MOP), which is intended to attack reinforced bunkers; up to two MOPs could be equipped in the B-2's bomb bays with one per bay,[93] the B-2 is the only platform compatible with the MOP as of 2012.[62] As of 2011, the AGM-158 JASSM cruise missile is an upcoming standoff munition to be deployed on the B-2 and other platforms.[94] This is to be followed by the Long Range Standoff Weapon, which may give the B-2 standoff nuclear capability for the first time.[95]

Avionics and systems

To make the B-2 more effective than previous bombers, many advanced and modern avionics systems were integrated into its design; these have been modified and improved following a switch to conventional warfare missions. One system is the low probability of intercept AN/APQ-181 multi-mode radar, a fully digital navigation system that is integrated with terrain-following radar and Global Positioning System (GPS) guidance, NAS-26 astro-inertial navigation system (first such system tested on the Northrop SM-62 Snark cruise missile)[96] and a Defensive Management System (DMS) to inform the flight crew of possible threats.[91] The onboard DMS is capable of automatically assessing the detection capabilities of identified threats and indicated targets.[97] The DMS will be upgraded by 2021 to detect radar emissions from air defenses to allow changes to the auto-router's mission planning information while in-flight so it can receive new data quickly to plan a route that minimizes exposure to dangers.[98]

For safety and fault-detection purposes, an on-board test system is linked with the majority of avionics on the B-2 to continuously monitor the performance and status of thousands of components and consumables; it also provides post-mission servicing instructions for ground crews.[99] In 2008, many of the 136[100] standalone distributed computers on board the B-2, including the primary flight management computer, were being replaced by a single integrated system.[101] The avionics are controlled by 13 EMP-resistant MIL-STD-1750A computers, which are interconnected through 26 MIL-STD-1553B-busses; other system elements are connected via optical fiber.[102]

In addition to periodic software upgrades and the introduction of new radar-absorbent materials across the fleet, the B-2 has had several major upgrades to its avionics and combat systems. For battlefield communications, both Link-16 and a high frequency satellite link have been installed, compatibility with various new munitions has been undertaken, and the AN/APQ-181 radar's operational frequency was shifted to avoid interference with other operators' equipment.[91] The arrays of the upgraded radar features were entirely replaced to make the AN/APQ-181 into an active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar.[103] Due to the B-2's composite structure, it is required to stay 40 miles (64 km) away from thunderstorms, to avoid static discharge and lightning strikes.[84]

Flight controls

To address the inherent flight instability of a flying wing aircraft, the B-2 uses a complex quadruplex computer-controlled fly-by-wire flight control system that can automatically manipulate flight surfaces and settings without direct pilot inputs to maintain aircraft stability.[104] The flight computer receives information on external conditions such as the aircraft's current air speed and angle of attack via pitot-static sensing plates, as opposed to traditional pitot tubes which would impair the aircraft's stealth capabilities.[105] The flight actuation system incorporates both hydraulic and electrical servoactuated components, and it was designed with a high level of redundancy and fault-diagnostic capabilities.[106]

Northrop had investigated several means of applying directional control that would infringe on the aircraft's radar profile as little as possible, eventually settling on a combination of split brake-rudders and differential thrust.[97] Engine thrust became a key element of the B-2's aerodynamic design process early on; thrust not only affects drag and lift but pitching and rolling motions as well.[107] Four pairs of control surfaces are located along the wing's trailing edge; while most surfaces are used throughout the aircraft's flight envelope, the inner elevons are normally only in use at slow speeds, such as landing.[108] To avoid potential contact damage during takeoff and to provide a nose-down pitching attitude, all of the elevons remain drooped during takeoff until a high enough airspeed has been attained.[108]

Stealth

The B-2's low-observable, or "stealth", characteristics enable the undetected penetration of sophisticated anti-aircraft defenses and to attack even heavily defended targets. This stealth comes from a combination of reduced acoustic, infrared, visual and radar signatures (multi-spectral camouflage) to evade the various detection systems that could be used to detect and be used to direct attacks against an aircraft. The B-2's stealth enables the reduction of supporting aircraft that are required to provide air cover, Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses and electronic countermeasures, making the bomber a "force multiplier". As of September 2013, there have been no instances of a missile being launched at a B-2.[73]

To reduce optical visibility during daylight flights, the B-2 is painted in an anti-reflective paint.[87] The undersides are dark because it flies at high altitudes (50,000 ft (15,000 m)), and at that altitude a dark grey painting blends well into the sky. It is speculated to have an upward-facing light sensor which alerts the pilot to increase or reduce altitude to match the changing illuminance of the sky.[109] The original design had tanks for a contrail-inhibiting chemical, but this was replaced in production aircraft by a contrail sensor that alerts the crew when they should change altitude.[110] The B-2 is vulnerable to visual interception at ranges of 20 nmi (23 mi; 37 km) or less.[73] The B-2 is stored in a $5 million specialised air-conditioned hangar to maintain its stealth coating. Every seven years, this coating is carefully washed away with crystallised wheat starch so that the B-2's surfaces can be inspected for any dents or scratches.[111]

Radar

Reportedly, the B-2 has a radar cross-section (RCS) of about 0.1 m2 (1.1 sq ft).[112] The bomber does not always fly stealthily; when nearing air defenses pilots "stealth up" the B-2, a maneuver whose details are secret. The aircraft is stealthy, except briefly when the bomb bay opens. The B-2's clean, low-drag flying wing configuration not only provides exceptional range but is also beneficial to reducing its radar profile.[71][113] The flying wing design most closely resembles a so-called infinite flat plate (as vertical control surfaces dramatically increase RCS), the perfect stealth shape, as it would lack angles to reflect back radar waves (initially, the shape of the Northrop ATB concept was flatter; it gradually increased in volume according to specific military requirements).[114] Without vertical surfaces to reflect radar laterally, side aspect radar cross section is also reduced.[115] Radars operating at a lower frequency band (S or L band) are able to detect and track certain stealth aircraft that have multiple control surfaces, like canards or vertical stabilizers, where the frequency wavelength can exceed a certain threshold and cause a resonant effect.[116]

RCS reduction as a result of shape had already been observed on the Royal Air Force's Avro Vulcan strategic bomber,[117] and the USAF's F-117 Nighthawk. The F-117 used flat surfaces (faceting technique) for controlling radar returns as during its development (see Lockheed Have Blue) in the early 1970s, technology only allowed for the simulation of radar reflections on simple, flat surfaces; computing advances in the 1980s made it possible to simulate radar returns on more complex curved surfaces.[118] The B-2 is composed of many curved and rounded surfaces across its exposed airframe to deflect radar beams. This technique, known as continuous curvature, was made possible by advances in computational fluid dynamics, and first tested on the Northrop Tacit Blue.[119][114]

Infrared

Some analysts claim infra-red search and track systems (IRSTs) can be deployed against stealth aircraft, because any aircraft surface heats up due to air friction and with a two channel IRST is a CO2 (4.3 µm absorption maxima) detection possible, through difference comparing between the low and high channel.[120][121]

Burying engines deep inside the fuselage also minimizes the thermal visibility or infrared signature of the exhaust.[87][122] At the engine intake, cold air from the boundary layer below the main inlet enters the fuselage (boundary layer suction, first tested on the Northrop X-21) and is mixed with hot exhaust air just before the nozzles (similar to the Ryan AQM-91 Firefly). According to the Stefan–Boltzmann law, this results in less energy (thermal radiation in the infrared spectrum) being released and thus a reduced heat signature. The resulting cooler air is conducted over a surface composed of heat resistant carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer and titanium alloy elements, which disperse the air laterally, to accelerate its cooling.[102] The B-2 lacks afterburners as the hot exhaust would increase the infrared signature; breaking the sound barrier would produce an obvious sonic boom as well as aerodynamic heating of the aircraft skin which would also increase the infrared signature.

Materials

According to the Huygens–Fresnel principle, even a very flat plate would still reflect radar waves, though much less than when a signal is bouncing at a right angle. Additional reduction in its radar signature was achieved by the use of various radar-absorbent materials (RAM) to absorb and neutralize radar beams. The majority of the B-2 is made out of a carbon-graphite composite material that is stronger than steel, lighter than aluminum, and absorbs a significant amount of radar energy.[75]

The B-2 is assembled with unusually tight engineering tolerances to avoid leaks as they could increase its radar signature.[82] Innovations such as alternate high frequency material (AHFM) and automated material application methods were also incorporated to improve the aircraft's radar-absorbent properties and reduce maintenance requirements.[87][123] In early 2004, Northrop Grumman began applying a newly developed AHFM to operational B-2s.[124] To protect the operational integrity of its sophisticated radar absorbent material and coatings, each B-2 is kept inside a climate-controlled hangar (Extra Large Deployable Aircraft Hangar System) large enough to accommodate its 172-foot (52 m) wingspan.[125]

Shelter system

B-2s are supported by portable, environmentally-controlled hangars called B-2 Shelter Systems (B2SS).[126] The hangars are built by American Spaceframe Fabricators Inc. and cost approximately US$5 million apiece.[126] The need for specialized hangars arose in 1998 when it was found that B-2s passing through Andersen Air Force Base did not have the climate-controlled environment maintenance operations required.[126] In 2003, the B2SS program was managed by the Combat Support System Program Office at Eglin Air Force Base. B2SS hangars are known to have been deployed to Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia and RAF Fairford.[126]

Operational history

1990s

The first operational aircraft, christened Spirit of Missouri, was delivered to Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, where the fleet is based, on 17 December 1993.[127] The B-2 reached initial operational capability (IOC) on 1 January 1997.[128] Depot maintenance for the B-2 is accomplished by USAF contractor support and managed at Oklahoma City Air Logistics Center at Tinker Air Force Base.[8] Originally designed to deliver nuclear weapons, modern usage has shifted towards a flexible role with conventional and nuclear capability.[87]

The B-2's combat debut was in 1999, during the Kosovo War. It was responsible for destroying 33% of selected Serbian bombing targets in the first eight weeks of U.S. involvement in the War.[8] During this war, six B-2s flew non-stop to Yugoslavia from their home base in Missouri and back, totaling 30 hours. Although the bombers accounted 50 sorties out of a total of 34,000 NATO sorties, they dropped 11 percent of all bombs.[129] The B-2 was the first aircraft to deploy GPS satellite-guided JDAM "smart bombs" in combat use in Kosovo.[130] The use of JDAMs and precision-guided munitions effectively replaced the controversial tactic of carpet-bombing, which had been harshly criticized due to it causing indiscriminate civilian casualties in prior conflicts, such as the 1991 Gulf War.[131] On 7 May 1999, a B-2 dropped five JDAMs on the Chinese Embassy, killing several staff.[132] By then, the B-2 had dropped 500 bombs in Yugoslavia.[133]

2000s

The B-2 saw service in Afghanistan, striking ground targets in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. With aerial refueling support, the B-2 flew one of its longest missions to date from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri to Afghanistan and back.[8] B-2s would be stationed in the Middle East as a part of a US military buildup in the region from 2003.[134]

The B-2's combat use preceded a USAF declaration of "full operational capability" in December 2003.[8] The Pentagon's Operational Test and Evaluation 2003 Annual Report noted that the B-2's serviceability for Fiscal Year 2003 was still inadequate, mainly due to the maintainability of the B-2's low observable coatings. The evaluation also noted that the Defensive Avionics suite had shortcomings with "pop-up threats".[8][135]

During the Iraq War, B-2s operated from Diego Garcia and an undisclosed "forward operating location". Other sorties in Iraq have launched from Whiteman AFB.[8] As of September 2013 the longest combat mission has been 44.3 hours.[73] "Forward operating locations" have been previously designated as Andersen Air Force Base in Guam and RAF Fairford in the United Kingdom, where new climate controlled hangars have been constructed. B-2s have conducted 27 sorties from Whiteman AFB and 22 sorties from a forward operating location, releasing more than 1,500,000 pounds (680,000 kg) of munitions,[8] including 583 JDAM "smart bombs" in 2003.[91]

2010s

In response to organizational issues and high-profile mistakes made within the USAF,[136][137] all of the B-2s, along with the nuclear-capable B-52s and the USAF's intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs), were transferred to the newly formed Air Force Global Strike Command on 1 February 2010.[138][139]

In March 2011, B-2s were the first U.S. aircraft into action in Operation Odyssey Dawn, the UN mandated enforcement of the Libyan no-fly zone. Three B-2s dropped 40 bombs on a Libyan airfield in support of the UN no-fly zone.[140] The B-2s flew directly from the U.S. mainland across the Atlantic Ocean to Libya; a B-2 was refueled by allied tanker aircraft four times during each round trip mission.[141][142]

In August 2011, The New Yorker reported that prior to the May 2011 U.S. Special Operations raid into Abbottabad, Pakistan that resulted in the death of Osama bin Laden, U.S. officials had considered an airstrike by one or more B-2s as an alternative; the use of a bunker busting bomb was rejected due to potential damage to nearby civilian buildings.[143] There were also concerns an airstrike would make it difficult to positively identify Bin Laden's remains, making it hard to confirm his death.[144]

On 28 March 2013, two B-2s flew a round trip of 13,000 miles (21,000 km) from Whiteman Air Force base in Missouri to South Korea, dropping dummy ordnance on the Jik Do target range. The mission, part of the annual South Korean–United States military exercises, was the first time that B-2s overflew the Korean peninsula. Tensions between the Koreas were high; North Korea protested against the B-2's participation and made threats of retaliatory nuclear strikes against South Korea and the United States.[145][146]

On 18 January 2017, two B-2s attacked an ISIS training camp 19 miles (30 km) southwest of Sirte, Libya, killing around 85 militants. The B-2s together dropped 108 500-pound (230 kg) precision-guided Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) bombs. These strikes were followed by an MQ-9 Reaper unmanned aerial vehicle firing Hellfire missiles. Each B-2 flew a 33-hour, round-trip mission from Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri with four or five (accounts differ) refuelings during the trip.[147][148]

Operators

United States Air Force (20 aircraft in active inventory)

- 509th Bomb Wing – Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri (19 B-2s)

- 13th Bomb Squadron 2005–present

- 325th Bomb Squadron 1998–2005

- 393rd Bomb Squadron 1993–present

- 394th Combat Training Squadron 1996–2018

- Air Combat Command

- 53d Wing – Eglin Air Force Base, Florida

- 72nd Test and Evaluation Squadron (Whiteman AFB, Missouri) 1998–present

- 325th Weapons Squadron – Whiteman AFB, Missouri 2005–present

- 715th Weapons Squadron 2003–2005

- Air National Guard

- 131st Bomb Wing (Associate) – Whiteman AFB, Missouri 2009–present

- 412th Test Wing – Edwards Air Force Base, California (has one B-2)

- 419th Flight Test Squadron 1997–present

- 420th Flight Test Squadron 1992–1997

- Air Force Systems Command

- 6510th Test Wing – Edwards AFB, California 1989–1992

- 6520th Flight Test Squadron

Accidents and incidents

On 23 February 2008, B-2 "AV-12" Spirit of Kansas crashed on the runway shortly after takeoff from Andersen Air Force Base in Guam.[149] Spirit of Kansas had been operated by the 393rd Bomb Squadron, 509th Bomb Wing, Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri, and had logged 5,176 flight hours. The two-person crew ejected safely from the aircraft. The aircraft was destroyed, a hull loss valued at US$1.4 billion.[150][151] After the accident, the USAF took the B-2 fleet off operational status for 53 days, returning on 15 April 2008.[152] The cause of the crash was later determined to be moisture in the aircraft's Port Transducer Units during air data calibration, which distorted the information being sent to the bomber's air data system. As a result, the flight control computers calculated an inaccurate airspeed, and a negative angle of attack, causing the aircraft to pitch upward 30 degrees during takeoff.[153] This was the first crash of a B-2 and the only loss as of 2024.

In February 2010, a serious incident involving a B-2 occurred at Andersen Air Force Base in Guam. The aircraft involved was AV-11 Spirit of Washington. The aircraft was severely damaged by fire while on the ground and underwent 18 months of repairs to enable it to fly back to the mainland U.S. for more comprehensive repairs.[154][155] Spirit of Washington was repaired and returned to service in December 2013.[156][157] At the time of the accident, the USAF had no training to deal with tailpipe fires on the B-2s.[158]

On the night of 13–14 September 2021, the B-2 Spirit of Georgia made an emergency landing at Whiteman AFB. The aircraft landed and went off the runway into the grass and came to rest on its left side.[159] The cause was later determined to be faulty landing gear springs and "microcracking" in hydraulic connections on the aircraft. The lock link springs in the left landing gear had likely not been replaced in at least a decade, and produced about 11% less tension than specified. The "microcracking" reduced hydraulic support to the landing gear. These problems allowed the landing gear to fold upon landing. The accident resulted in a minimum of $10.1 million in repair damages, but the final repair cost was still being determined in March 2022.[160][161]

On 10 December 2022, an in-flight malfunction aboard a B-2 forced an emergency landing at Whiteman AFB.[162] No personnel, including the flight crew, sustained injuries during the incident; there was a post-crash fire that was quickly put out.[163] Subsequently, all B-2s were grounded.[164] On 18 May 2023, Air Force officials lifted the grounding without disclosing any details about what caused the incident, or what steps had been taken return the aircraft to operation.[165]

Aircraft on display

No operational B-2s have been retired by the Air Force to be put on display. B-2s have made occasional appearances on ground display at various air shows.

B-2 test article (s/n AT-1000), the second of two built without engines or instruments and used for static testing, was placed on display in 2004 at the National Museum of the United States Air Force near Dayton, Ohio.[166] The test article passed all structural testing requirements before the airframe failed.[166] The museum's restoration team spent over a year reassembling the fractured airframe. The display airframe is marked to resemble Spirit of Ohio (S/N 82-1070), the B-2 used to test the design's ability to withstand extreme heat and cold.[166] The exhibit features Spirit of Ohio's nose wheel door, with its Fire and Ice artwork, which was painted and signed by the technicians who performed the temperature testing.[166] The restored test aircraft is on display in the museum's "Cold War Gallery".[167]

Specifications (B-2A Block 30)

Data from USAF Fact Sheet,[8] Pace,[168] Spick,[72] Northrop Grumman[notes 1][169]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2: pilot (left seat) and mission commander (right seat)

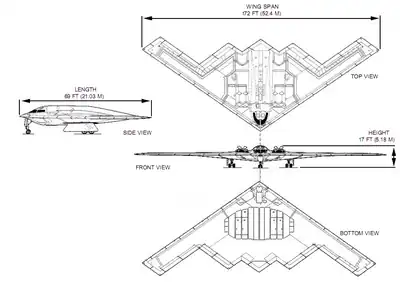

- Length: 69 ft 0 in (21.0 m)

- Wingspan: 172 ft 0 in (52.4 m)

- Height: 17 ft 0 in (5.18 m)

- Wing area: 5,140 sq ft (478 m2)

- Empty weight: 158,000 lb (71,700 kg)

- Gross weight: 336,500 lb (152,200 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 376,000 lb (170,600 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 167,000 pounds (75,750 kg)

- Powerplant: 4 × General Electric F118-GE-100 non-afterburning turbofans, 17,300 lbf (77 kN) thrust each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 630 mph (1,010 km/h, 550 kn) at 40,000 ft (12,000 m) altitude / Mach 0.95 at sea level[168]

- Cruise speed: 560 mph (900 km/h, 487 kn) at 40,000 ft (12,000 m) altitude

- Range: 6,900 mi (11,000 km, 6,000 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 50,000 ft (15,200 m)

- Wing loading: 67.3 lb/sq ft (329 kg/m2)

- Thrust/weight: 0.205

Armament

- 2 internal bays for ordnance and payload with an official limit of 40,000 lb (18,000 kg); maximum estimated limit is 50,000 lb (23,000 kg)[72]

- 80× 500 lb (230 kg) class bombs (Mk-82, GBU-38) mounted on Bomb Rack Assembly (BRA)

- 36× 750 lb (340 kg) CBU class bombs on BRA

- 16× 2,000 lb (910 kg) class bombs (Mk-84, GBU-31) mounted on Rotary Launcher Assembly (RLA)

- 16× B61 or B83 nuclear bombs on RLA (strategic mission)

- Standoff weapon: AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW) and AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM)[170][171]

- 2× GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator[172]

Individual aircraft

| Air Vehicle No. | Block No.[173] | USAF s/n | Formal name | Time in service, status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AV-1 | Test/30 | 82-1066 | Spirit of America | 14 July 2000 – Active[174] |

| AV-2 | Test/30 | 82-1067 | Spirit of Arizona | 4 December 1997 – Active |

| AV-3 | Test/30 | 82-1068 | Spirit of New York | 10 October 1997 – Active |

| AV-4 | Test/30 | 82-1069 | Spirit of Indiana | 22 May 1999 – Active |

| AV-5 | Test/20 | 82-1070 | Spirit of Ohio | 18 July 1997 – Active |

| AV-6 | Test/30 | 82-1071 | Spirit of Mississippi | 23 May 1997 – Active |

| AV-7 | 10 | 88-0328 | Spirit of Texas | 21 August 1994 – Active |

| AV-8 | 10 | 88-0329 | Spirit of Missouri | 31 March 1994 – Active |

| AV-9 | 10 | 88-0330 | Spirit of California | 17 August 1994 – Active |

| AV-10 | 10 | 88-0331 | Spirit of South Carolina | 30 December 1994 – Active |

| AV-11 | 10 | 88-0332 | Spirit of Washington | 29 October 1994 – Severely damaged by fire in February 2010,[154] repaired[156] |

| AV-12 | 10 | 89-0127 | Spirit of Kansas | 17 February 1995 – 23 February 2008, crashed[149] |

| AV-13 | 10 | 89-0128 | Spirit of Nebraska | 28 June 1995 – Active |

| AV-14 | 10 | 89-0129 | Spirit of Georgia | 14 November 1995 – Suffered damage to the wing following a landing gear collapse in September 2021.[175] Undergoing repairs at Plant 42[176] |

| AV-15 | 10 | 90-0040 | Spirit of Alaska | 24 January 1996 – Active |

| AV-16 | 10 | 90-0041 | Spirit of Hawaii | 10 January 1996 – Suffered damage to the wing following an emergency landing in December 2022 (cause is still under investigation by the Air Force).[177] |

| AV-17 | 20 | 92-0700 | Spirit of Florida | 3 July 1996 – Active |

| AV-18 | 20 | 93-1085 | Spirit of Oklahoma | 15 May 1996 – Active, Flight Test |

| AV-19 | 20 | 93-1086 | Spirit of Kitty Hawk | 30 August 1996 – Active |

| AV-20 | 30 | 93-1087 | Spirit of Pennsylvania | 5 August 1997 – Active |

| AV-21 | 30 | 93-1088 | Spirit of Louisiana | 11 November 1997 – Active |

| AV-22 through AV-165 | Cancelled | |||

Notable appearances in media

See also

Related lists

- List of active United States military aircraft

- List of bomber aircraft

- List of flying wing aircraft

- List of aerospace megaprojects

Notes

- ↑ Maximum takeoff weight is classified; listed figure is based on statement from manufacturer that aircraft's payload capacity is at least 40,000 lb.

References

- 1 2 3 "Northrop B-2A Spirit fact sheet." Archived 28 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Mehuron, Tamar A., Assoc. Editor. "2009 USAF Almanac, Fact and Figures." Archived 13 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, May 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Thornborough, A.M.; Stealth, Aircraft Illustrated special, Ian Allan (1991).

- 1 2 "B-2 Spirit". United States Air Force. Archived from the original on 25 June 2023. Retrieved 14 July 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "B-2 Bomber: Cost and Operational Issues Letter Report, GAO/NSIAD-97-181." Archived 22 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine United States General Accounting Office (GAO), 14 August 1997. Retrieved 13 December 2018.

- ↑ Rolfsen, Bruce. "Moisture confused sensors in B-2 crash." Air Force Times, 9 June 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- 1 2 admin (9 February 2018). "USAF to Retire B-1, B-2 in Early 2030s as B-21 Comes On-Line". Air & Space Forces Magazine. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "B-2 Spirit Fact Sheet." Archived 26 January 2017 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Air Force. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Rao, G.A. and S.P. Mahulikar. "Integrated review of stealth technology and its role in airpower". Aeronautical Journal, v. 106 (1066), 2002, pp. 629–641.

- ↑ Crickmore and Crickmore 2003, p. 9.

- ↑ "Stealth Aircraft." Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, 2003. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ Griffin & Kinnu 2007, pp. 14–15

- ↑ [the integrator, Northrop Grumman (newspaper), Volume 8, No. 12, 30 June 2006, page 8 article author: Carol Ilten].

- ↑ Withington 2006, p. 7

- 1 2 Goodall 1992,

- 1 2 3 Pace 1999, pp. 20–27

- 1 2 3 Rich & Janos 1996

- ↑ "Northrop B-2A Spirit". joebaugher.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2018. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- ↑ Donald 2003, p. 13

- ↑ Sweetman 1991, pp. 21, 30.

- ↑ Spick 2000, p. 339

- ↑ Van Voorst, Bruce. "The Stealth Takes Wing." Time, 31 July 1989. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Griffin & Kinnu 2007, pp. ii–v

- ↑ YouTube. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2015 – via YouTube.

- ↑ Vartaebedian, Ralph. "Defense worker loses job over his ties to India". Archived 7 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times, 16 February 1993.

- ↑ Atkinson, Rick. "Unraveling Stealth's 'Black World';Questions of Cost and Mission Arise Amid Debate Over Secrecy Series: Project Senior C.J.; The Story Behind The B-2 Bomber Series Number: 2/3." The Washington Post, 9 October 1989.

- 1 2 Pace 1999, pp. 29–36.

- ↑ Norris, Guy (2 December 2022). "The Story Behind Aviation Week's B-2 Rollout Photo Scoop". aviationweek.com.

- ↑ AP. "Stealth bomber classified documents missing." Archived 15 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 24 June 1987. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "Thomas Patrick Cavanaugh". Locate a Federal Inmate. Federal Bureau of Prisons. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2023.

- ↑ "Press Release." FBI Honolulu. Retrieved:: 1 December 2010.

- ↑ Foster, Peter. "Engineer jailed for selling US stealth bomber technology to China." Archived 3 July 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Telegram, 24 January 2011.

- ↑ Pace 1999, pp. 75–76

- ↑ "President George H. Bush's State of the Union Address." c-span.org, 28 January 1992. Retrieved 13 September 2009. Archived 24 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Graham, Bradley. "US to add one B-2 plane to 20 plane fleet." The Washington Post, 22 March 1996, p. A20.

- ↑ Eden 2004, pp. 350–353.

- ↑ Capaccio, Tony. "The B-2's Stealthy Skins Need Tender, Lengthy Care." Defense Week, 27 May 1997, p. 1.

- ↑ US General Accounting Office September 1996, pp. 53, 56.

- ↑ "The Gold Plated Hangar Queen Survives." Archived 17 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine Strategyworld.com, 14 June 2010. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ↑ Murphy, Robert D., Michael J. Hazard, Jeffrey T. Hunter, and James F. Dinwiddie. B-2 Bomber: Status of Cost, Development, and Production. No. GAO/NSIAD-95-164. GENERAL ACCOUNTING OFFICE WASHINGTON DC NATIONAL SECURITY AND INTERNATIONAL A FFAIRS DIV, August 1995, p.16, 20

- ↑ US General Accounting Office, October 1996, p.4, 23/

- 1 2 Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 30 November 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- ↑ Axe, David. "Why Can't the Air Force Build an Affordable Plane?" Archived 23 April 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Atlantic, 26 March 2012. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ↑ Trimble, Stephen (26 August 2011). "US Air Force combat fleet's true operational costs revealed". The DEW Line. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 1 July 2012.

- 1 2 Schmitt, Eric. "Key Senate Backer of Stealth Bomber Sees It in Jeopardy." Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 14 September 1991. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ Torry, Jack; Wehrman, Jessica (6 July 2015). "Kasich still touts opposition to stealth bomber". Columbus Dispatch. Archived from the original on 25 October 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ↑ Sorenson 1995, p. 168

- ↑ "Moisture in sensors led to stealth bomber crash, Air Force report says." Kansas City Star, 5 June 2008.

- ↑ "Zell Miller's Attack on Kerry: A Little Out Of Date." Archived 14 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine FactCheck.org, 4 October 2004. Retrieved 26 October 2004.

- ↑ Bender, Brian and John Robinson. "More Stealth Bombers Mean Less Combat Power". Defense Daily, 5 August 1997, p. 206.

- ↑ US General Accounting Office September 1996, p. 70.

- ↑ US General Accounting Office September 1996, p. 72.

- ↑ "Debate on Dellums Amendment to 1998 Defense Authorization Act." Archived 9 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine fas.org, 23 June 1997.

- ↑ McKinney, Brooks. "Air Force Completes Preliminary Design Review of New B-2 Bomber Computer Architecture." Archived 21 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine Northrop Grumman, 7 July 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ "Semantic Designs Aligns with Northrop Grumman to Modernize B-2 Spirit Bomber Software Systems" Archived 9 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine. Semantic Designs. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ↑ McKinney, Brooks. "Northrop Grumman Adding Mobile Targets to B-2 Bomber Capabilities." Archived 12 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine Northrop Grumman, 7 February 2008. Retrieved 29 October 2009.

- ↑ "B-2 radar modernization program contract awarded." US Air Force, 30 December 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Warwick, Graham. "USAF Awards B-2 Radar Upgrade Production." Aviation Week, 30 December 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Jennings, Gareth. "B-2 passes modernisation milestones." Archived 31 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine Janes, 24 July 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "New Composite to Improve B-2 Durability." Defense-Update, 19 November 2010. Archived 28 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Grant, Rebecca. "Nukes for NATO." Archived 7 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, July 2010.

- 1 2 Kelley, Michael. "The Air Force Announced It's Upgrading The One Plane It Needs To Bomb Iran." Archived 12 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine Business Insider, 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Mitchell Institute Aerospace Advantage Podcast "Flying and Fighting in the B-2: America’s Stealth Bomber" Archived 4 August 2021 at the Wayback Machine Mitchell Institute, 11 April 2021. Retrieved 12 April 2021.

- ↑ "Pentagon Wants Unmanned Stealth Bomber to Replace B-2." Archived 14 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Los Angeles Times via uasvision.com, 24 March 2011.

- ↑ Schogol, Jeff. |topnews|text|FRONTPAGE "Schwartz Defends Cost of USAF's Next-Gen Bomber" . Defense News. 29 February 2012.

- ↑ Less, Eloise. "Questions about whether the US needs another $55 billion worth of bombers." Archived 12 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine Business Insider, 27 March 2012.

- ↑ "Bolstering Spirits in the Year of the B-2". af.mil. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Osborn, Kris (25 June 2014). "B-2 Bomber Set to Receive Massive Upgrade". dodbuzz.com. Monster. Archived from the original on 23 February 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ↑ Tirpak, John A. "The Bomber Roadmap" Archived 29 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Air Force Magazine, June 1999. Retrieved 30 December 2015 (PDF version Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine)

- ↑ Grant, Rebecca. "Return of the Bomber, The Future of Long-Range Strike", p. 11, 17, 29. Air Force Association, February 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Croddy and Wirtz 2005, pp. 341–342.

- 1 2 3 Spick 2000, pp. 340–341

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Chiles, James R. (September 2013). "The Stealth Bomber Elite". Air & Space. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ↑ Sweetman 2005, pp. 73–74

- 1 2 Boyne 2002, p. 466

- ↑ Fitzsimons 1978, p. 2282

- ↑ Noland, David. "Bombers: Northrop B-2 Archived 25 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine" Infoplease, 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "The B-2 Spirit stealth bomber Archived 25 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine" Military Heat, 2007. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "B-49 – United States Nuclear Forces". Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- ↑ Heppenheimer, T. A. (September 1986). "Stalth – First glimpses of the invisible aircraft now under construction". Popular Science. p. 76. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 27 October 2020.

- ↑ "B-2 Spirit Stealth Bomber Facts" (PDF). Northrop Grumman. 14 March 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- 1 2 Tirpak, John A. (April 1996). "With the First B-2 Squadron". Air Force Magazine. 79 (4). Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- ↑ Kenagy, David N., Christopher T. Bird, Christopher M. Webber and Joseph R. Fischer. "Dextroamphetamine Use During B-2 Combat Mission." Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, Volume 75, Number 5, May 2004, pp. 381–386.

- 1 2 Langewiesche, William (July 2018). "An Extraordinarily Expensive Way to Fight ISIS". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018.

- 1 2 Tucker 2010, p. 39

- ↑ Moir & Seabridge 2008, p. 398

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Tucker 2010, p. 177

- ↑ Richardson 2001, pp. 120–121

- ↑ Rip & Hasik 2002, p. 201

- ↑ Rip & Hasik 2002, pp. 242–246

- 1 2 3 4 "Air Force programs: B-2." Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Project On Government Oversight (POGO), 16 April 2004. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Evans 2004, p. 13

- ↑ Mayer, Daryl. "Northrop Grumman and USAF Verify Proper Fit of 30,000 lb Penetrator Weapon on B-2 Bomber." Archived 21 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine defpro.com, 22 July 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "AGM-158 JASSM Cruise Missiles: FY 2011 Orders." Archived 2 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Defense Industry Daily, 14 May 2011.

- ↑ Kristensen, Hans M. (22 April 2013). "B-2 Stealth Bomber To Carry New Nuclear Cruise Missile". FAS Strategic Security Blog. Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 22 April 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Sweetman, Bill (1999). Inside the Stealth Bomber. Zenith Imprint. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-61060-689-9. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- 1 2 Sweetman 2005, p. 73

- ↑ Air Force Upgrades B-2 Stealth Bomber as Modern Air Defenses Advance Archived 26 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine – Military.com, 24 April 2015

- ↑ Siuru 1993, p. 118

- ↑ Air Warfare. ABC-CLIO. 2002. p. 466. ISBN 978-1-57607-345-2. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ Page, Lewis. "Upgrade drags Stealth Bomber IT systems into the 90s." Archived 10 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Register, 11 July 2008.

- 1 2 Jane's Aircraft Upgrades 2003, p. 1711f

- ↑ "AN/APQ-181 Radar System." Archived 24 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine Raytheon. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ↑ Moir & Seabridge 2008, p. 397

- ↑ Moir & Seabridge 2008, pp. 256–258

- ↑ "Flight Control Actuation System Integrator for the B-2 Spirit." Archived 22 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine Moog. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ↑ Chudoba 2001, p. 76

- 1 2 Chudoba 2001, pp. 201–202

- ↑ Sweetman, Bill (1999). Inside the Stealth Bomber. Zenith Imprint. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-61060-689-9. Archived from the original on 15 February 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ Gosnell, Mariana. "Why contrails hang around." Archived 12 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Air & Space magazine, 1 July 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Sebastien Roblin (11 November 2018). "Why the Air Force Only Has 20 B-2 Spirit Stealth Bombers". National Interest. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 5 November 2020.

- ↑ Richardson 2001, p. 57

- ↑ Siuru 1993, pp. 114–115

- 1 2 "B-2: The Spirit of Innovation" (PDF). Northrop Grumman Corporation. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 April 2023. Retrieved 15 October 2023.

- ↑ Osborn, Kris (15 November 2018). "America's New B-21 Stealth Bomber vs. Russia's S-300 or S-400: Who Wins?". nationalinterest.org. Archived from the original on 15 November 2018. Retrieved 16 November 2018.

- ↑ Majumdar, Dave (8 November 2018). "How Russia Could Someday Shootdown an F-22, F-35 or B-2 Stealth Bomber". nationalinterest.org. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ↑ Dawson 1957, p. 3.

- ↑ Rich 1994, p. 21

- ↑ Christopher Lavers (2012). Reeds Vol 14: Stealth Warship Technology. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4081-7553-8. Archived from the original on 5 February 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ Radar, Cordless. "RAND Report Page 37". Flight International. Archived from the original on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 16 December 2010.

- ↑ "VI – STEALTH AIRCRAFT: EAGLES AMONG SPARROWS?". Federation of American Scientist. Archived from the original on 13 February 2008. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ↑ Croddy and Wirtz 2005, p. 342.

- ↑ Lewis, Paul. "B-2 to receive maintenance boost." Archived 16 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine Flight International, 5 March 2002.

- ↑ Hart, Jim. "Northrop Grumman Applies New Coating to Operational B-2." Archived 9 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine "Northrop Grumman Integrated Systems", 19 April 2004.

- ↑ Fulghum, D.A. "First F-22 large-scale, air combat exercise wins praise and triggers surprise" (online title), "Away Game". Aviation Week & Space Technology, 8 January 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 Specht, Wayne (16 January 2003). "Portable B-2 bomber shelters are built ... in parts (officially) unknown". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 25 June 2018. Retrieved 24 June 2018.

- ↑ Pace 1999, p. 66

- ↑ Pace 1999, p. 73

- ↑ Ho, David (30 June 1999). "Air Force Says Bomber Performed Well". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ↑ Hansen, Staff Sgt. Ryan. "JDAM continues to be warfighter's weapon of choice." US Air Force, 17 March 2006. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Tucker 2010, pp. 177–178

- ↑ Rip & Hasik 2002, p. 398

- ↑ Diamond, John (7 May 1999). "B-2s Turn Out Not To Be Solo Flyers". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ↑ "Pressure mounts as stealth bombers deployed". The Age, 28 February 2003.

- ↑ Tucker 2010, p. 178

- ↑ McNeil, Kirsten. "Air Force Reorganizes Nuclear Commands." Archived 2 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine armscontrol.org, December 2012.

- ↑ "US plans separate nuclear command." Archived 26 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 25 October 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "Air Force Global Strike Command officials assume B-52, B-2 mission." United States Air Force, 2 February 2010.

- ↑ Chavanne, Bettina H. "USAF Creates Global Strike Command." Archived 11 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Week, 24 October 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ Martin, David. "Crisis in Libya: U.S. bombs Qaddafi's airfields." Archived 21 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine CBS News, 20 March 2011.

- ↑ Tirpak, John A. "Bombers Over Libya." Archived 30 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine Air Force Magazine, July 2011.

- ↑ Marcus, Jonathan. "Libya military operation: Who should command?" Archived 29 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, 21 March 2011.

- ↑ Schmidle, Nicholas. "Getting Bin Laden." Archived 13 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine The New Yorker, 8 August 2011.

- ↑ "US had planned air strike to level Osama's Abbottabad hideout: Americas, News – India Today". India Today. Archived from the original on 15 August 2022. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ US flies stealth bombers over South Korea Archived 3 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine Agence France-Presse, 28 April 2013.

- ↑ U.S. flies B-2 stealth bombers to S. Korea in "extended deterrence mission" aimed at North Archived 28 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine CBS News, 28 March 2013.

- ↑ Tomlinson, Lucas (19 January 2017). "B-2 bombers kill nearly 100 ISIS terrorists in Libya". Fox News. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- ↑ Langewiesche, William (July–August 2018). "An Extraordinarily Expensive Way to Fight ISIS". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- 1 2 "B-2 Crashes on Takeoff From Guam." Aviation Week, 23 February 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2009.

- ↑ "Air Force: Sensor moisture caused 1st B-2 crash." Archived 4 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine USA Today, 5 June 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2009.

- ↑ "B-2 crash video." Archived 4 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine YouTube. Retrieved 23 July 2009.

- ↑ Linch, Airman 1st Class Stephen. "B-2s return to flight after safety pause." US Air Force, 21 April 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- ↑ "B-2 accident report released." Archived 5 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine US Air Force, 6 June 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

- 1 2 jeremigio. "B-2 Fire at AAFB Back in February of 2010 Was 'Horrific,' Not 'Minor'." Archived 22 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine pncguam.com, 31 August 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ↑ Mayer, Daryl. "Program office brings home 'wounded warrior'." Archived 20 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine wpafb.af.mil. Retrieved: 5 January 2012.

- 1 2 Candy Knight. ""Spirit of Washington" rises from the ashes". Whiteman.af.mil. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

- ↑ Hennigan, W. J., "The $105M resurrection of a B-2 stealth bomber", Los Angeles Times, 22 March 2014

- ↑ Hemmerdinger, Jon (27 March 2014). "USAF updates firefighter training and equipment following B-2 tailpipe fire". FlightGlobal. Archived from the original on 14 December 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ "B-2 Spirit sitting wing down after landing mishap". The War Zone. September 2021. Archived from the original on 14 August 2022.

- ↑ RIEDEL, ALEXANDER (18 March 2022). "Faulty landing gear springs led to B-2 bomber crash last year, report finds". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on 12 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ↑ Cocke, Robert P.M. (12 January 2022). "United States Air Force / Abbreviated Aircraft Accident Investigation / B-2A, T/N 89-0129 / Whiteman Air Force Base, Missouri / 14 September 2021" (PDF). United States Air Force Judge Advocate General's Corps. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ↑ Helfrich, Emma (12 December 2022). "Runway At Whiteman AFB Remains Closed After B-2 Bomber Accident". The Drive. Archived from the original on 13 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ↑ Epstein, Jake. "A B-2 stealth bomber's emergency landing sparked a fire and damaged the plane, but the crew walked away unharmed". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 17 December 2022.

- ↑ "B-2 nuke bomber fleet is temporarily grounded due to safety issue | CNN Politics". CNN. 21 December 2022. Archived from the original on 22 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- ↑ Gordon, Chris (18 May 2023). "B-2 Safety Pause Lifted, Flights Set to Resume Within Days". Air And Space Forces Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 22 May 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 "Factsheet: Northrop B-2 Spirit." Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 24 August 2011.

- ↑ "Cold War Gallery." Archived 15 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine National Museum of the United States Air Force. Retrieved: 24 August 2011.

- 1 2 Pace 1999, Appendix A

- ↑ "B-2 Technical Details". Northrop Grumman. Retrieved 27 October 2023.

- ↑ Dan Petty. "The US Navy – Fact File: AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW)". Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ "JASSM". Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- ↑ "New Video Of B-2 Bomber Dropping Mother Of All Bunker Busters Sends Ominous Message". The War Zone. 17 May 2019. Archived from the original on 29 May 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ↑ All 21 copies brought to Block 30 standard.

- ↑ "Air Force names final B-2 bomber 'Spirit of America" Archived 9 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine. fas.org, 14 July 2000. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ↑ Losey, Stephen (17 March 2022). "Old, weak landing gear springs led to a B-2's $10M skid off the runway". Sightline Media Group. Defense News. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ Trevithick, Joseph (22 September 2022). "Damaged B-2 Returns To Palmdale For Repairs A Year After Landing Mishap". The War Zone. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ↑ Cohen, Rachel (12 December 2022). "B-2 stealth bomber damaged in Missouri emergency landing". Air Force Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2023. Retrieved 15 December 2022.

- ↑ Pace 1999, Appendix

- ↑ "B-2." Archived 9 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine fas.org. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

Bibliography

- "Air Force, Options to Retire or Restructure the Force Would Reduce Planned Spending, NSIAD-96-192." US General Accounting Office, September 1996.

- Boyne, Walter J. (2002), Air Warfare: an International Encyclopedia: A-L, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-345-2

- Chudoba, Bernd (2001), Stability and Control of Conventional and Unconventional Aircraft Configurations: A Generic Approach, Stoughton, Wisconsin: Books on Demand, ISBN 978-3-83112-982-9

- Crickmore, Paul and Alison J. Crickmore, "Nighthawk F-117 Stealth Fighter". North Branch, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint, 2003. ISBN 0-76031-512-4.

- Croddy, Eric and James J. Wirtz. Weapons of Mass Destruction: An Encyclopedia of Worldwide Policy, Technology, and History, Volume 2. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 1-85109-490-3.

- Dawson, T.W.G., G.F. Kitchen and G.B. Glider. Measurements of the Radar Echoing Area of the Vulcan by the Optical Simulation Method. Farnborough, Hants, UK: Royal Aircraft Establishment, September 1957 National Archive Catalogue file, AVIA 6/20895

- Donald, David, ed. (2003), Black Jets: The Development and Operation of America's Most Secret Warplanes, Norwalk, Connecticut: AIRtime, ISBN 978-1-880588-67-3

- Donald, David (2004), The Pocket Guide to Military Aircraft: And the World's Airforces, London: Octopus Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-681-03185-2

- Eden, Paul. "Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit". Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. New York: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- Evans, Nicholas D. (2004), Military Gadgets: How Advanced Technology is Transforming Today's Battlefield – and Tomorrow's, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: FT Press, ISBN 978-0-1314-4021-0

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. (1978), Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons and Warfare, vol. 21, London: Phoebus, ISBN 978-0-8393-6175-6

- Goodall, James C. "The Northrop B-2A Stealth Bomber." America's Stealth Fighters and Bombers: B-2, F-117, YF-22, and YF-23. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing Company, 1992. ISBN 0-87938-609-6.

- Griffin, John; Kinnu, James (2007), B-2 Systems Engineering Case Study (PDF), Dayton, Ohio: Air Force Center for Systems Engineering, Air Force Institute of Technology, Wright Patterson Air Force Base, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2009

- Moir, Ian; Seabridge, Allan G. (2008), Aircraft Systems: Mechanical, Electrical and Avionics Subsystems Integration, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-4700-5996-8

- Pace, Steve (1999), B-2 Spirit: The Most Capable War Machine on the Planet, New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-134433-3

- Pelletier, Alain J. "Towards the Ideal Aircraft: The Life and Times of the Flying Wing, Part Two". Air Enthusiast, No. 65, September–October 1996, pp. 8–19. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Richardson, Doug (2001), Stealth Warplanes, London: Salamander Books Ltd, ISBN 978-0-7603-1051-9

- Rich, Ben R.; Janos, Leo (1996), Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years of Lockheed, Boston: Little, Brown & Company, ISBN 978-0-3167-4300-6

- Rich, Ben (1994), Skunk Works, New York: Back Bay Books, ISBN 978-0-316-74330-3

- Rip, Michael Russell; Hasik, James M. (2002), The Precision Revolution: Gps and the Future of Aerial Warfare, Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, ISBN 978-1-5575-0973-4

- Siuru, William D. (1993), Future Flight: The Next Generation of Aircraft Technology, New York: McGraw-Hill Professional, ISBN 978-0-8306-4376-9

- Sorenson, David, S. (1995), The Politics of Strategic Aircraft Modernization, New York: Greenwood, ISBN 978-0-275-95258-7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Spick, Mike (2000), B-2 Spirit, The Great Book of Modern Warplanes, St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI, ISBN 978-0-7603-0893-6

- Sweetman, Bill (2005), Lockheed Stealth, North Branch, Minnesota: Zenith Imprint, ISBN 978-0-7603-1940-6

- Sweetman, Bill. "Inside the stealth bomber". Zenith Imprint, 1999. ISBN 1610606892.

- Tucker, Spencer C (2010), The Encyclopedia of Middle East Wars: The United States in the Persian Gulf, Afghanistan, and Iraq Conflicts, Volume 1, Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-8510-9947-4

- Withington, Thomas (2006), B-1B Lancer Units in Combat, Botley Oxford, UK: Osprey, ISBN 978-1-8417-6992-9

Further reading

- Richardson, Doug. Northrop B-2 Spirit (Classic Warplanes). New York: Smithmark Publishers Inc., 1991. ISBN 0-8317-1404-2.

- Sweetman, Bill. Inside the Stealth Bomber. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 1999. ISBN 0-7603-0627-3.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. "Northrop B-2 Spirit". Modern Military Aircraft (Aviation Factfile). Rochester, Kent, UK: Grange Books plc, 2004. ISBN 1-84013-640-5.

- The World's Great Stealth and Reconnaissance Aircraft. New York: Smithmark, 1991. ISBN 0-8317-9558-1.

External links

- B-2 Spirit fact sheet and gallery on U.S. Air Force site

- B-2 Spirit page on Northrop Grumman site Archived 3 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- B-2 Stealth Bomber article on How It Works Daily

- B-2 Spirit News Articles