| Part of a series on the |

| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

|

The Tang dynasty (618–907) of ancient China witnessed many advancements in Chinese science and technology, with various developments in woodblock printing, timekeeping, mechanical engineering, medicine, and structural engineering.

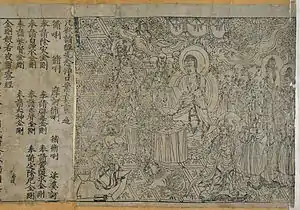

Woodblock printing

The popularization of woodblock printing during the Tang dynasty made the written word available to greater audiences. As a result of the much wider distribution and circulation of reading materials, the general populace were for the first time able to purchase affordable copies of texts, which correspondingly led to greater literacy.[1] While the immediate effects of woodblock printing did not create a drastic change in Chinese society, in the long term, the accumulated effects of increased literacy enlarged the talent pool to encompass civilians of broader social-economic circumstances and backgrounds, who would be seen entering the imperial examinations and passing them by the later Song dynasty.[2][3][4] The extent of woodblock printing is attested to by one of the world's oldest surviving printed documents, a miniature Buddhist dharani sutra unearthed at Xi'an in 1974, dating roughly from 650 to 670.[5] A copy of the Diamond Sutra found at Dunhuang is the earliest surviving full-length book printed at regular size, complete with illustrations embedded within the text and dated precisely to 868.[6][7] Among the earliest documents to be printed were Buddhist texts as well as calendars, the latter essential for calculating and marking which days were auspicious and which days were not.[8] The commercial success and profitability of woodblock printing was attested to by one British observer at the end of the nineteenth century, who noted that even before the arrival of western printing methods, the price of books and printed materials in China had already reached an astoundingly low price compared to what could be found in his home country. Of this, he said:

We have an extensive penny literature at home, but the English cottager cannot buy anything like the amount of printed matter for his penny that the Chinaman can for even less. A penny Prayer-book, admittedly sold at a loss, cannot compete in mass of matter with many of the books to be bought for a few cash in China. When it is considered, too, that a block has been laboriously cut for each leaf, the cheapness of the result is only accounted for by the wideness of sale.[9]

Although Bi Sheng later invented the movable type system in the eleventh century, Tang dynasty style woodblock printing would remain the dominant mode of printing in China until a newer model of printing press from Europe became used in East Asia.[10] However, the decisive breakthrough in China was not the Gutenberg letterpress, but lithography, a nineteenth-century technological marvel almost wholly forgotten in Europe.[11]

Playing cards

Playing cards may have been invented during the Tang dynasty around the ninth century AD as a result of the usage of woodblock printing technology.[12][13][14][15][16] The first possible reference to card games comes from a ninth-century text known as the Collection of Miscellanea at Duyang, written by Tang dynasty writer Su E. It describes Princess Tongchang, daughter of Emperor Yizong of Tang, playing the "leaf game" in 868 with members of the clan of Wei Baoheng, the family of the princess' husband.[14][17][18]: 131 The first known book on the "leaf" game was called the Yezi Gexi and allegedly written by a Tang woman. It received commentary by writers of subsequent dynasties.[19] The Song dynasty (960–1279) scholar Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) asserts that the "leaf" game existed at least since the mid-Tang dynasty and associated its invention with the development of printed sheets as a writing medium.[19][14] However, Ouyang also claims that the "leaves" were pages of a book used in a board game played with dice, and that the rules of the game were lost by 1067.[20]

Other games revolving around alcoholic drinking involved using playing cards of a sort from the Tang dynasty onward. However, these cards did not contain suits or numbers. Instead, they were printed with instructions or forfeits for whoever drew them.[20]

The earliest dated instance of a card game involving cards with suits and numerals occurred on 17 July 1294 when two gamblers, Yan Sengzhu and Zheng Pig-Dog, were arrested for playing with zi pai. Authorities impounded nine of their cards along with wood blocks for printing them.[20]

William Henry Wilkinson suggests that the first cards may have been actual paper currency which doubled as both the tools of gaming and the stakes being played for,[13] similar to trading card games. Using paper money was inconvenient and risky so they were substituted by play money known as "money cards". One of the earliest games in which we know the rules is Madiao, a trick-taking game, which dates to the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Fifteenth-century scholar Lu Rong described it is as being played with 38 "money cards" divided into four suits: 9 in coins, 9 in strings of coins (which may have been misinterpreted as sticks from crude drawings), 9 in myriads (of coins or of strings), and 11 in tens of myriads (a myriad is 10,000). The two latter suits had Water Margin characters instead of pips on them [18]: 132 with Chinese characters to mark their rank and suit. The suit of coins is in reverse order with 9 of coins being the lowest going up to 1 of coins as the high card.[21]

Clockworks and timekeeping

Technology during the Tang period was built also upon the precedents of the past. The mechanical gear systems of Zhang Heng (78–139) and Ma Jun (fl. 3rd century) gave the Tang engineer, astronomer, and monk Yi Xing (683–727) inspiration when he invented the world's first clockwork escapement mechanism in 725.[22] This was used alongside a clepsydra clock and waterwheel to power a rotating armillary sphere in representation of astronomical observation.[23] Yi Xing's device also had a mechanically timed bell that was struck automatically every year, and a drum that was struck automatically every quarter-hour; essentially, a striking clock.[24] Yi Xing's astronomical clock and water-powered armillary sphere became well known throughout the country, since students attempting to pass the imperial examinations by 730 had to write an essay on the device as an exam requirement.[25] However, the most common type of public and palace timekeeping device was the inflow clepsydra. Its design was improved c. 610 by the Sui-dynasty engineers Geng Xun and Yuwen Kai. They provided a steelyard balance that allowed seasonal adjustment in the pressure head of the compensating tank and could then control the rate of flow for different lengths of day and night.[26]

Mechanical delights and automatons

There were many other mechanical inventions during the Tang era. This included a 0.91 m (3 ft) tall mechanical wine server of the early eighth century that was in the shape of an artificial mountain, carved out of iron and rested on a lacquered-wooden tortoise frame.[27] This intricate device used a hydraulic pump that siphoned wine out of metal dragon-headed faucets, as well as tilting bowls that were timed to dip wine down, by force of gravity when filled, into an artificial lake that had intricate iron leaves popping up as trays for placing party treats.[27] Furthermore, as the historian Charles Benn describes it:

Midway up the southern side of the mountain was a dragon...the beast opened its mouth and spit brew into a goblet seated on a large [iron] lotus leaf beneath. When the cup was 80% full, the dragon ceased spewing ale, and a guest immediately seized the goblet. If he was slow in draining the cup and returning it to the leaf, the door of a pavilion at the top of the mountain opened and a mechanical wine server, dressed in a cap and gown, emerged with a wooden bat in his hand. As soon as the guest returned the goblet, the dragon refilled it, the wine server withdrew, and the doors of the pavilion closed...A pump siphoned the ale that flowed into the ale pool through a hidden hole and returned the brew to the reservoir [holding more than 16 quarts/15 liters of wine] inside the mountain.

— [27]

Although the use of a teasing mechanical puppet in this wine-serving device was certainly ingenious, the use of mechanical puppets in China date back to the Qin dynasty (221–207 BC)[29] while Ma Jun in the third century had an entire mechanical puppet theater operated by the rotation of a waterwheel.[29] There was also an automatic wine-server known in the ancient Greco-Roman world, a design of Heron of Alexandria that employed an urn with an inner valve and a lever device similar to the one described above. There are many stories of automatons used in the Tang, including general Yang Wulian's wooden statue of a monk who stretched his hands out to collect contributions; when the amount of coins reached a certain weight, the mechanical figure moved his arms to deposit them in a satchel.[30] This weight-and-lever mechanism was exactly like Heron's penny slot machine.[31] Other devices included one by Wang Ju, whose "wooden otter" could allegedly catch fish; Needham suspects a spring trap of some kind was employed here.[30]

Medicine

The Chinese of the Tang era were also very interested in the benefits of officially classifying all of the medicines used in pharmacology. In 657, Emperor Gaozong of Tang (r. 649–683) commissioned the literary project of publishing an official materia medica, complete with text and illustrated drawings for 833 different medicinal substances taken from different stones, minerals, metals, plants, herbs, animals, vegetables, fruits, and cereal crops.[32] In addition to compiling pharmacopeias, the Tang fostered learning in medicine by upholding imperial medical colleges, state examinations for doctors, and publishing forensic manuals for physicians.[33] Authors of medicine in the Tang include Zhen Qian (d. 643) and Sun Simiao (581–682), the former who first identified in writing that patients with diabetes had an excess of sugar in their urine, and the latter who was the first to recognize that diabetic patients should avoid consuming alcohol and starchy foods.[34] As written by Zhen Qian and others in the Tang, the thyroid glands of sheep and pigs were successfully used to treat goiters; thyroid extracts were not used to treat patients with goiter in the West until 1890.[35]

Structural engineering

In the realm of technical Chinese architecture, there were also government standard building codes, outlined in the early Tang book of the Yingshan Ling (National Building Law).[37] Fragments of this book have survived in the Tang Lü (The Tang Code),[38] while the Song architectural manual of the Yingzao Fashi (State Building Standards) in 1103 is the oldest existing technical treatise on Chinese architecture that has survived in full.[37] During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (712–756) there were 34,850 registered craftsmen serving the state, managed by the Agency of Palace Buildings (Jingzuo Jian).[38]

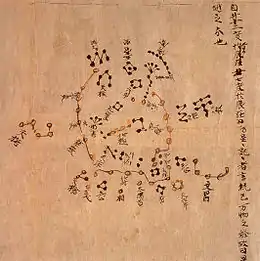

Cartography

In the realm of cartography, there were further advances beyond the map-makers of the Han dynasty. When the Tang chancellor Pei Ju (547–627) was working for the Sui dynasty as a Commercial Commissioner in 605, he created a well-known gridded map with a graduated scale in the tradition of Pei Xiu (224–271).[39][40] The Tang chancellor Xu Jingzong (592–672) was also known for his map of China drawn in the year 658.[40] In the year 785 the Emperor Dezong had the geographer and cartographer Jia Dan (730–805) complete a map of China and her former colonies in Central Asia.[40] Upon its completion in 801, the map was 9.1 m (30 ft) in length and 10 m (33 ft) in height, mapped out on a grid scale of one inch equaling one hundred li (Chinese unit of measuring distance).[40] A Chinese map of 1137 is similar in complexity to the one made by Jia Dan, carved on a stone stele with a grid scale of 100 li.[41] However, the only type of map that has survived from the Tang period are star charts. Despite this, the earliest extant terrain maps of China come from the ancient State of Qin; maps from the fourth century BC that were excavated in 1986.[42]

Alchemy, gas cylinders, and air conditioning

The Chinese of the Tang period employed complex chemical formulas for an array of different purposes, often found through experiments of alchemy. These included a waterproof and dust-repelling cream or varnish for clothes and weapons, fireproof cement for glass and porcelain wares, a waterproof cream applied to silk clothes of underwater divers, a cream designated for polishing bronze mirrors, and many other useful formulas.[43] The vitrified, translucent ceramic known as porcelain was invented in China during the Tang, although many types of glazed ceramics preceded it.[44][45]

Ever since the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), the Chinese had drilled deep boreholes to transport natural gas from bamboo pipelines to stoves where cast iron evaporation pans boiled brine to extract salt.[46] During the Tang dynasty, a gazetteer of Sichuan province stated that at one of these 182 m (600 ft) 'fire wells', men collected natural gas into portable bamboo tubes which could be carried around for dozens of km (mi) and still produce a flame.[47] These were essentially the first gas cylinders; Robert Temple assumes some sort of tap was used for this device.[47]

The inventor Ding Huan (fl. 180 AD) of the Han dynasty invented a rotary fan for air conditioning, with seven wheels 3 m (10 ft) in diameter and manually powered.[48] In 747, Emperor Xuanzong had a "Cool Hall" built in the imperial palace, which the Tang Yulin (唐語林) describes as having water-powered fan wheels for air conditioning as well as rising jet streams of water from fountains.[49] During the subsequent Song dynasty, written sources mentioned the air conditioning rotary fan as even more widely used.[50]

Citations

- ↑ Graff 2002, p. 19.

- ↑ Ebrey, Walthall & Palais 2006, p. 159.

- ↑ Fairbank & Goldman 2006, p. 94.

- ↑ Ebrey 1999, p. 147.

- ↑ Pan 1997, pp. 979–980.

- ↑ Temple 1986, p. 112.

- ↑ Needham 1986d, p. 151.

- ↑ Ebrey 1999, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Barrett 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Needham 1986d, p. 227.

- ↑ Barrett 2008, p. 13.

- ↑ Needham 1986d, pp. 131–132.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, W.H. (1895). "Chinese Origin of Playing Cards" (PDF). American Anthropologist. VIII (1): 61–78. doi:10.1525/aa.1895.8.1.02a00070.

- 1 2 3 Lo, A. (2009). "The game of leaves: An inquiry into the origin of Chinese playing cards". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 63 (3): 389–406. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00008466.

- ↑ Needham 2004, p. 328 "it is also now rather well-established that dominoes and playing-cards were originally Chinese developments from dice."

- ↑ Needham 2004, p. 334 "Numbered dice, anciently widespread, were on a related line of development which gave rise to dominoes and playing-cards (+9th-century China)."

- ↑ Zhou, Songfang (1997). "On the Story of Late Tang Poet Li He". Journal of the Graduates Sun Yat-sen University. 18 (3): 31–35.

- 1 2 Needham, Joseph and Tsien Tsuen-hsuin. (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press., reprinted Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.(1986)

- 1 2 Needham 2004, p. 132

- 1 2 3 Parlett, David, "The Chinese "Leaf" Game", March 2015.

- ↑ Money-suited playing cards at The Mahjong Tile Set

- ↑ Needham 1986a, p. 319.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, pp. 473–475.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, pp. 473–474.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, p. 475.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, p. 480.

- 1 2 3 Benn 2002, p. 144.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, p. 160.

- 1 2 Needham 1986b, p. 158.

- 1 2 Needham 1986b, p. 163.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, p. 163 footnote c.

- ↑ Benn 2002, p. 235.

- ↑ Adshead 2004, p. 83.

- ↑ Temple 1986, pp. 132–133.

- ↑ Temple 1986, pp. 134–135.

- ↑ Xi 1981, p. 464.

- 1 2 Guo 1998, p. 1.

- 1 2 Guo 1998, p. 3.

- ↑ Needham 1986a, pp. 538–540.

- 1 2 3 4 Needham 1986a, p. 543.

- ↑ Needham 1986a, p. Plate LXXXI.

- ↑ Hsu 1993, p. 90.

- ↑ Needham 1986e, p. 452.

- ↑ Adshead 2004, p. 80.

- ↑ Wood 1999, p. 49.

- ↑ Temple 1986, pp. 78–79.

- 1 2 Temple 1986, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, pp. 99, 151, 233.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, pp. 134, 151.

- ↑ Needham 1986b, p. 151.

Sources

- Adshead, S. A. M. (2004), T'ang China: The Rise of the East in World History, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-4039-3456-7 (hardback).

- Barrett, Timothy Hugh (2008), The Woman Who Discovered Printing, Great Britain: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-12728-7 (alk. paper)

- Benn, Charles (2002), China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-517665-0

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley; Walthall, Anne; Palais, James B. (2006), East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 978-0-618-13384-0

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1999), The Cambridge Illustrated History of China, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-66991-7 (paperback)

- Fairbank, John King; Goldman, Merle (2006) [1992], China: A New History (2nd enlarged ed.), Cambridge: MA; London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-01828-0

- Graff, David A. (2002), Medieval Chinese Warfare, 300-900, Warfare and History, London: Routledge, ISBN 978-0415239554

- Guo, Qinghua (1998), "Yingzao Fashi: Twelfth-Century Chinese Building Manual", Architectural History, 41: 1–13, doi:10.2307/1568644, JSTOR 1568644

- Hsu, Mei-ling (1993), "The Qin Maps: A Clue to Later Chinese Cartographic Development", Imago Mundi, 45 (1): 90–100, doi:10.1080/03085699308592766

- Needham, Joseph (1986a), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 3, Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, Taipei: Caves Books

- Needham, Joseph (1986b), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Engineering, Part 2, Mechanical Engineering, Taipei: Caves Books

- Needham, Joseph (1986d), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing, Taipei: Caves Books

- Needham, Joseph (1986e), Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts, Taipei: Caves Books

- Needham, Joseph (2004), Kenneth Girdwood Robinson (ed.), Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 7, The Social Background, Part 2, General Conclusions and Reflections, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-08732-5

- Pan, Jixing (1997), "On the Origin of Printing in the Light of New Archaeological Discoveries", Chinese Science Bulletin, 42 (12): 976–981, doi:10.1007/BF02882611, ISSN 1001-6538

- Temple, Robert (1986), The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention, with a foreword by Joseph Needham, New York: Simon and Schuster, ISBN 978-0-671-62028-8

- Wood, Nigel (1999), Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 978-0-8122-3476-3

- Xi, Zezong (1981), "Chinese Studies in the History of Astronomy, 1949-1979", Isis, 72 (3): 456–470, doi:10.1086/352793