| Three Departments and Six Ministries | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 三省六部 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Tam tỉnh lục bộ | ||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 三省六部 | ||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||

| Hangul | 삼성육부 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

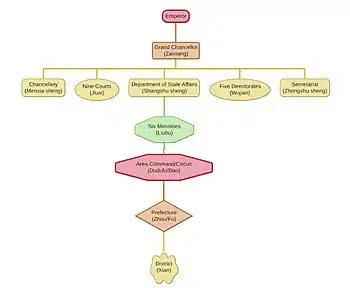

The Three Departments and Six Ministries (Chinese: 三省六部; pinyin: Sān Shěng Liù Bù) system was the primary administrative structure in imperial China from the Sui dynasty (581–618) to the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368). It was also used by Balhae (698–926) and Goryeo (918–1392) and various other kingdoms in Manchuria, Korea and Vietnam.

The Three Departments were three top-level administrative structures in imperial China. They were the Central Secretariat, responsible for drafting policy, the Chancellery, responsible for reviewing policy and advising the emperor, and the Department of State Affairs, responsible for implementing policy. The former two were loosely joined as the Secretariat-Chancellery during the late Tang dynasty, Song dynasty and in the Korean kingdom of Goryeo.

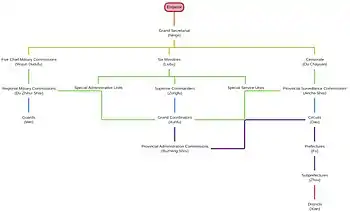

The Six Ministries (also translated as Six Boards) were direct administrative organs of the state under the authority of the Department of State Affairs. They were the Ministries of Personnel, Rites, War, Justice, Works, and Revenue. During the Yuan Dynasty, authority over the Six Ministries was transferred to the Central Secretariat.

The Three Departments were abolished by the Ming dynasty, but the Six Ministries continued under the Ming and Qing, as well as in Vietnam and Korea.

Three Departments and Six Ministries during the Tang dynasty

| Emperor (皇帝, huángdì) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chancellery (t 門下省, s 门下省, Ménxiàshěng) | Department of State Affairs (t 尚書省, s 尚书省, Shàngshūshěng) | Secretariat (t 中書省, s 中书省, Zhōngshūshěng) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ministry of Personnel (吏部, Lìbù) | Ministry of Revenue (t 戶部, s 户部, Hùbù) | Ministry of Rites (t 禮部, s 礼部, Lǐbù) | Ministry of War (兵部, Bīngbù) | Ministry of Justice (刑部, Xíngbù) | Ministry of Works (工部, Gōngbù) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Early history

Before the Three Departments and Six Ministries, the central administrative structure of the Qin and Han dynasties was the Three Lords and Nine Ministers (三公九卿, Sāngōng Jiǔqīng) system. Nonetheless, even then, offices which fulfilled the same functions as the later three departments were already in existence.

The Department of State Affairs originated in the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC) in an archival capacity. During the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BC), the department's office was instituted as a channel of communications between the Emperor's advisors and the government as a whole. By the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220), an office of advisors and reviewers had also been set up. Under the reign of Emperor Wen of Wei (r. 220–226), the Central Secretariat was formally created to draft imperial edicts and to balance out the powerful Department of State Affairs[1] The office of the Chancellery was first instituted during the Jin dynasty (266–420) and carried on throughout the Northern and Southern Dynasties period (420–589), where it often became the most powerful office in the central government.

Three Departments

Department of State Affairs

- The Department of State Affairs (尚書省, Shàngshūshěng), also known as the Imperial Secretariat, was the primary executive institution of imperial China, head of the Six Ministries, the Nine Courts, and the Three Directorates (sometimes five). The Department of State of Affairs existed in one form or another from Han dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD) until the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), but was never re-established in the following Ming dynasty.

The Department of State Affairs originated as one of the Six Chief Stewards (liushang 六尚) that were responsible for headgear, wardrobe, food, the bath, the bedchamber and for writing (shangshu 尚書, literally "presenting writings"), during the Qin dynasty. The position of Chief Steward for writing (shangshu) became more important during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BC), who tried to escape the influence of the Grand Chancellor and Censor-in-Chief(yushi dafu 御史大夫) by relying on other officials. Emperor Guangwu of Han (r. 25–57) created the Department of State Affairs with the shangshu as head of the six sections of government. It was headed by a Director (ling 令) and a Vice Director (puye 僕射), assisted by a left and right aide (cheng 丞) and 36 attendant gentlemen (shilang 侍郎), six for each section, as well as 18 clerks (lingshi 令史), three for each section. These six sections later became the Six Ministries, and their chief stewards, the Director, and Vice Director were collectively known as the eight executives (bazuo 八座). The power of the Department of State Affairs decreased in the succeeding dynasties of Cao Wei and the Jin dynasty (266–420) as some of its functions and authority were delegated to the Central Secretariat and Chancellery. The posts of Director and Vice Director also became less important as it was bestowed upon high ministers and noble family members who did not participate in the administrative activities of the department. Real paperwork became the purview of clerks, whose increasing influence frightened Emperor Wu of Liang. Emperor Wu decreed that only nobility should become clerks, but none of the nobles were willing to assign their sons to such a lowly position. Members of the department refused to cooperate with Emperor Wu and resisted any changes to administration. The Department of State Affairs in the Sixteen Kingdoms and Northern dynasties tended to work more similarly to the Southern dynasties over time but were dominated by barbarian peoples such as the Xianbei.[2]

During the Sui dynasty (581-618), the post of Director was often left vacant while two Vice Directors, Gao Jiong and Yang Su, handled affairs.[3]

During the Tang dynasty (618-907), the post of Director continued to be left vacant for the most part, and when it was filled, it was by the heir apparent like Li Shimin (r. 626–649) or Li Shi (r. 779–804). To weaken the power of the Vice Director, who was de facto head of the institution, the position was divided into left and right Vice Directors, with the former being the senior. At times the Vice Directors were comparable in power with the Grand Chancellor and sometimes even superseded him. However, by the mid-Tang period the Grand Chancellors had regained their predominance, and Vice Directors of the department were required to have special designations to participate in policy making discussions. Thereafter the department became a purely executive institution. The six sections of government were formally divided into the Six Ministries, each headed by a Minister (shangshu). The six divisions were replicated at the local prefectural level, and each directly reported to their respective ministries in the central government. In addition to the Six Ministires, the Department of State Affairs was also in charge of the Nine Courts and Three Directorates. The Department of State Affairs was one of the largest employers in the government and provided income and posts for many officials. The institution lasted until the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and was never re-established in the following Ming dynasty.[4]

Six Ministries

The Six Ministries (六部 Liù Bù), also known as the "Six Boards," were government agencies directed by the Department of State Affairs and formally institutionalized during the Cao Wei and Jin dynasty (266–420) periods. Each ministry was headed by a Minister or Secretary (Chinese: 尚書; pinyin: shàngshū; Manchu: ![]() ) who was assisted by two Vice-Ministers or Secretaries (Chinese: 侍郎; pinyin: shìláng; Manchu:

) who was assisted by two Vice-Ministers or Secretaries (Chinese: 侍郎; pinyin: shìláng; Manchu: ![]() ). Each ministry was divided into four bureaus (si si 四司) responsible for local administration, each headed by a director (langzhong 郎中), who was assisted by a vice director (yuanwailang 員外郎). The Six Ministries structure was purely administrative. Sometimes they shared administrative duties with parallel structures such as the Three Bureaus and the Bureau of Military Affairs. The Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) transferred authority over the Six Ministries to the Central Secretariat. The succeeding Ming dynasty (1368–1644) abolished the Central Secretariat entirely and put the Six Ministries under the direct control of the emperor. In 1901 and 1906, the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) added new ministries to the structure, making the term "Six Ministries" obsolete.[5]

). Each ministry was divided into four bureaus (si si 四司) responsible for local administration, each headed by a director (langzhong 郎中), who was assisted by a vice director (yuanwailang 員外郎). The Six Ministries structure was purely administrative. Sometimes they shared administrative duties with parallel structures such as the Three Bureaus and the Bureau of Military Affairs. The Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) transferred authority over the Six Ministries to the Central Secretariat. The succeeding Ming dynasty (1368–1644) abolished the Central Secretariat entirely and put the Six Ministries under the direct control of the emperor. In 1901 and 1906, the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) added new ministries to the structure, making the term "Six Ministries" obsolete.[5]

- The Ministry of Personnel or Civil Appointments (吏部, Lìbù) was in charge of appointments, merit ratings, promotions, and demotions of officials, as well as granting of honorific titles.[6]

- The Ministry of Revenue or Finance (戶部, Hùbù) was in charge of gathering census data, collecting taxes and handling state revenues, while there were two offices of currency that were subordinate to it.[7]

- The Ministry of Rites (禮部, Lǐbù) was in charge of state ceremonies, rituals and sacrifices; it also oversaw registers for Buddhist and Daoist priesthoods and even the reception of envoys from tributary states;[8] it also dealt with China's foreign relations prior to the establishment of the Zongli Yamen in 1861. It also managed the imperial examinations.

- The Ministry of War or Defense (兵部, Bīngbù) was in charge of the appointments, promotions and demotions of military officers, the maintenance of military installations, equipment and weapons, as well as the courier system.[9] In times of war, high-ranking officials in the Ministry also served as strategists and advisers to frontline commanders. Sometimes, they even served as frontline commanders themselves.

- The Ministry of Justice or Punishments (刑部, Xíngbù) was in charge of judicial and penal processes, but had no supervisory role over the Censorate or the Grand Court of Revision.[10]

- The Ministry of Works or Public Works (工部, Gōngbù) was in charge of government construction projects, hiring of artisans and laborers for temporary service, manufacturing government equipment, the maintenance of roads and canals, standardisation of weights and measures, and the gathering of resources from the countryside.[10]

Nine Courts

The Nine Courts throughout most of history were:

| Court | Minister |

|---|---|

| Court of Imperial Sacrifices (太常寺) | Minister of Ceremonies (太常) |

| Court of Imperial Entertainments (光祿寺) | Minister of the Household (光祿勳) |

| Court of the Imperial Clan (宗正寺 or 宗人府) | Minister of the Imperial Clan (宗正) |

| Court of the Imperial Stud (太僕寺) | Minister Coachman (太僕) |

| Court of the Imperial Treasury (太府寺) | Minister Steward (少府) |

| Court of the Imperial Regalia (衛尉寺) | Minister of the Guards (衛尉) |

| Court of State Ceremonial (鴻臚寺) | Minister Herald (大鴻臚) |

| Court of the National Granaries (司農寺) | Minister of Finance (大司農) |

| Court of Judicature and Revision (大理寺) | Minister of Justice (廷尉/大理) |

Three/Five Directorates

The Three Directorates, or sometimes five, were originally the Directorates of Waterways, Imperial Manufactories, and Palace Buildings. In the Sui dynasty, the Directorate of Armaments or Palace Domestic Service was sometimes counted as one. The Sui and Tang dynasties also added the Directorate of Education to the list. The Directorate of Astronomy was added during the Song dynasty.

| Directorate | Transliteration | Chinese |

|---|---|---|

| Directorate of Waterways | dushuijian | 都水監 |

| Directorate for Imperial Manufactories | shaofujian | 少府監 |

| Directorate for Palace Buildings | jiangzuojian | 將作監 |

| Directorate for Armaments | junqijian | 軍器監 |

| Directorate of Palace Domestic Service | changqiujian | 長秋監 |

| Directorate of Education | guozijian | 國子監 |

| Directorate of Astronomy | sitianjian | 司天監 |

Central Secretariat

- The Central Secretariat (中書省, Zhōngshūshěng), also known as the Palace Secretariat or simply the Secretariat, was the main policy-formulating agency that was responsible for proposing and drafting all imperial decrees, but its actual function varied at different times.

The Central Secretariat originated during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (r. 141-87 BC) to handle documents. The chief steward for writing (shangshu 尚書), aided by eunuch secretary-receptionists (zhongshu yezhe 中書謁者)), forwarded documents to the inner palace. This organization was headed by a Secretariat Director (zhongshu ling 中書令) assisted by a Vice Director (zhongshu puye 中書仆射). These two posts came to assert significant political influence on the court, causing eunuchs to be forbidden from holding these posts by the end of the Western Han dynasty. This institution continued after the end of the Han dynasty into Cao Wei and it was Emperor Wen of Wei who formally created the Central Secretariat, headed by a Secretariat Supervisor (zhongshu jian 中書監) and a Director (zhongshu ling 中書令). Although lower in rank than the Department of State Affairs, the personnel of the Central Secretariat worked closer to the emperor and were responsible for drafting edits, and therefore their content. Under the Wei, the Central Secretariat was also in charge of the palace library, but this responsibility was terminated during the Jin dynasty (266–420). In the Northern and Southern dynasties, the personnel ranged from princes and high ranking family members to professional writers. The position and responsibilities of the Central Secretariat varied greatly in this period, sometimes even being put in charge of judicial and entertainment matters.[11]

The Central Secretariat was known by a variety of names during the Sui dynasty and Tang dynasty. The Sui called it neishisheng (內史省) or neishusheng (內書省). Emperor Gaozong of Tang (r. 618–626) called it the "Western Terrace" (xitai 西臺), Wu Zetian (regent 684–690, ruler 690–704) called it the "Phoenix Tower" (fengge 鳳閣), and Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (r. 712–755) named it the "Department of the Purple Mystery" (ziweisheng 紫微省). During the Sui-Tang period, the duty of the Central Secretariat was to read incoming material to the throne, answer questions from the emperor, and to draft imperial edicts. The Sui and Tang added posts for compilation of the imperial diary and proof-reading documents. In the Sui dynasty, the Central Secretariat Director was sometimes the same person as the Grand Chancellor (zaixiang 宰相). In the Tang, the Director was also master of court assemblies, and often where Grand Chancellors started their careers. The Central Secretariat Director took part in conferences with the emperor alongside the directors of the Department of State Affairs and the Chancellery. In the latter half of the Tang dynasty, the title of Director of the Central Secretariat was given to jiedushi (military commissioners) to give them a higher status, which deprived the title of its real value. The Hanlin Academy gained prominence as its academicians (xueshi 學士) began processing and drafting documents in place of the Central Secretariat, which allowed emperors to issue edicts without prior consultation with Secretariat staff.[12]

During the early Song dynasty (960–1279), the Central Secretariat was formally demoted and its function reduced to processing less important documents like memorials, resubmitted documents, or lists of examinations. The Central Secretariat no longer had a Director and its office was merged with that of the Chancellery, called Secretariat-Chancellery (zhongshu menxia 中書門下, shortened zhongshu 中書) or Administration Chamber (zhengshitang). Drafting documents became the function of a new Document Drafting Office (sherenyuan 舍人院). A reform during the Yuanfeng reign-period (1078-1085) restored the Central Secretariat to its former functions and the Document Drafting Office was renamed the Secretariat Rear Section (zhongshu housheng 中書後省). However the title of Director remained an honorific while real leadership of the Central Secretariat went to the Right Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs (shangshu you puye 尚書右仆射, or youcheng 右丞), who also held the title of Court Gentleman of the Central Secretariat (zhongshu shilang 中書侍郎). Another Court Gentleman of the Central Secretariat managed the institution and participated in court consultations. The Rear Section was managed by a Secretariat Drafter (zhongshu sheren). The Left Vice Director (zuo puye 左仆射, or zuocheng 左丞) held the titles of Court Gentleman of the Chancellery (menxia shilang 門下侍郎) and Grand Chancellor concurrently. Policy decisions were made by the Grand Chancellor before the edicts and documents were drafted and issued. In the Southern Song period (1127-1279), the Central Secretariat was merged with the Chancellery again. The Right Vice Director became Grand Chancellor of the Right while the Court Gentleman of the Central Secretariat became Vice Grand Chancellor.[13]

The Khitan dominated Liao dynasty (907–1125) had an institution similar in function to the Central Secretariat of the early Tang dynasty, called the Department of Administration (zhengshisheng 政事省). The posts of Director, Vice Director, and the drafters, were mostly held by Chinese.[14]

The Jurchen dominated Jin dynasty (1115–1234) had a Central Secretariat that functioned similarly to the Song institution, but the paperwork was done by academicians rather than professional drafters. The Right Chancellor of the Central Secretariat (shangshu you chengxiang 尚書右丞相) was subordinate to the Grand Chancellor. Emperor Wanyan Liang (r. 1149–1160) abolished the institution.[15]

The Mongol dominated Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) made the Central Secretariat the central administrative office and abolished the Department of State Affairs in 1292 (revived 1309–1311). The post of Director was held by an imperial prince or left vacant, however real work went to the right and left Grand Chancellors. Under the Grand Chancellors were four managers of governmental affairs (pingzhang zhengshi 平章政事) and a right and left aide (you cheng 右丞, zuo cheng 左丞), who were collectively known as state counsellors (zaizhi 宰執). Below the state counsellors there were four consultants (canyi zhongshusheng shi 參議中書省事) responsible for paperwork and took part in decisions. The Central Secretariat controlled the Six Ministries and was thus functionally the heart of the government. The regions of what are now Shandong, Shanxi, Hebei and Inner Mongolia were directly subordinate to the Central Secretariat.[16]

In the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the Hongwu Emperor became suspicious of the chancellor Hu Weiyong and executed him in 1380. The Central Secretariat was also abolished and its functions delegated to the Hanlin Academy and Grand Secretariat.[17]

Chancellery

- The Chancellery (門下省, Ménxiàshěng) advised the Emperor and the Central Secretariat, and reviewed edicts and commands. As the least important of the three departments, it was discontinued after the Song dynasty. After Hu Weiyong's incident in the early Ming dynasty, the Three Departments and Six Ministries structure was formally replaced by the Six Ministries structure.

The Chancellery was originally the Court of Attendants in the Han dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD), which oversaw all palace attendants. It was not until the Cao Wei and Jin dynasty (266–420) era that the institution of Chancellery was formalized. The Chancellery was led by a Director (menxia shizhong 門下侍中), with assistance from a gentleman attendant at the palace gate (Huangmen shilang 黃門侍郎 or jishi Huangmen shilang 給事黃門侍郎), later called Vice Director (menxia shilang 門下侍郎). They were responsible for advising the emperor and providing consultation prior to the issuing of edicts. During the Southern dynasties period, the Chancellery became responsible for the imperial coaches, medicine, provisions and the stables. During the Sui dynasty (581-618), it also became responsible for the city gates, the imperial seals, the wardrobe and the palace administration. These new external duties were reduced in the Tang dynasty (618-907) to just the city gates, the insignia, and the Institute for the Advancement of Literature. The Tang assigned several lower-ranking officials to the Chancellery to make records for the imperial diary.[18]

The Tang called the Chancellery, headed by the Grand Chancellor, a number of different names such as the Eastern Terrace (Dongtai 東臺) or the Phoenix Terrace (Luantai 鸞臺). In cases where the Vice Directors of the Chancellery or Central Secretariat were officiating as Grand Chancellor, a supervising secretary (jishizhong), took over their work in the Chancellery. The position of supervising secretary originated in the Department of State Affairs, from where they were transferred to the Chancellery in the early Tang period. They were responsible for studying the drafts of memorials and implementing corrections before they were presented to the emperor.[19]

The Chancellery began to decline in significance during the mid-Tang period as it competed in political power with the Central Secretariat. Ultimately control over the flow and content of court documents shifted over to the Central Secretariat. By the 9th century, the Chancellery was only responsible for the imperial seals, court ceremonies and the imperial altars. Some of its officials took care of lists of state examinees and household registers of state officials, while others were assigned to resubmit documents. Many of the associated titles were purely honorifics.[20]

The Chancellery only continued to exist in name during the Song dynasty (960–1279) while its functions were carried out by the Central Secretariat and the Department of State Affairs. For example, the Left Vice Director of the Department of State Affairs was concurrently Director of the Chancellery. The Chancellery was reorganized into several different sections: personnel, revenue, military, rites, justice, works, the secretary's office, the office for ministerial routine memorandums, and finally the proclamations archive. In 1129, the Chancellery was merged with the Central Secretariat and became the Secretariat-Chancellery (zhongshu menxia 中書門下, shortened zhongshu 中書) or Administration Chamber (zhengshitang).[21]

The Chancellery was also used in the Liao dynasty and the Jurchen Jin dynasty. In the Jin dynasty, it was abolished in 1156. The Mongol-led Yuan dynasty decided not to revive the institution.[22]

Other Departments

Aside from the "Three Departments", there were three others equal in status to them, but they are rarely involved in the administration of the state.

- The Department of the Palace (殿中省, Diànzhōngshěng) was responsible for the upkeep of the imperial household and the palace grounds.

- The Department of Secret Books (祕書省, Mìshūshěng) was responsible for keeping the imperial library.

- The Department of Service (內侍省, Nèishìshěng) was responsible for staffing the palace with eunuchs.

See also

- Political systems of Imperial China

- Grand Secretariat, the highest institution in the Ming dynasty

- Censorate, the central supervisory agency in Imperial China

- Three Lords and Nine Ministers, forerunner to the Three Departments and Six Ministries

- Six Ministries of Joseon, a similar 13th-century Korean political structure

- Six Ministries of the Nguyễn dynasty

- Five Yuans of the Republic of China

- Six branches of the Government of the People's Republic of China

- Ministries of the People's Republic of China

References

Citations

- ↑ Lu 2008, p. 235.

- ↑ "shangshusheng 尚書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "shangshusheng 尚書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "shangshusheng 尚書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "liubu 六部 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ Hucker 1958, p. 32.

- ↑ Hucker 1958, p. 33.

- ↑ Hucker 1958, pp. 33–35.

- ↑ Hucker 1958, p. 35.

- 1 2 Hucker 1958, p. 36.

- ↑ "zhongshusheng 中書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "zhongshusheng 中書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "zhongshusheng 中書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "zhongshusheng 中書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "zhongshusheng 中書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "zhongshusheng 中書省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "neige 内閣 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "menxiasheng 門下省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "menxiasheng 門下省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "menxiasheng 門下省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "menxiasheng 門下省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

- ↑ "menxiasheng 門下省 (www.chinaknowledge.de)".

Sources

- Twitchett, Dennis, ed. (1979). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China, 589–906 AD, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-0-521-21446-9.

- Hucker, Charles O. (December 1958). "Governmental Organization of the Ming Dynasty". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 21: 1–66. doi:10.2307/2718619. JSTOR 2718619.

- Li, Konghuai (2007). History of Administrative Systems in Ancient China (in Chinese). Joint Publishing (H.K.) Co., Ltd. ISBN 978-962-04-2654-4.

- Lu, Simian (2008). The General History of China (in Chinese). New World Publishing. ISBN 978-7-80228-569-9.

- Mote, Frederick W. (2003) [1999]. Imperial China: 900–1800 (HUP paperback ed.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01212-7.

- Wang, Yü-Ch'üan (June 1949). "An Outline of the Central Government of the Former Han Dynasty". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. Harvard-Yenching Institute. 12 (1/2): 134–187. doi:10.2307/2718206. JSTOR 2718206.