| Scrotum | |

|---|---|

Human scrotum in a relaxed state (left) and a tense state (right) | |

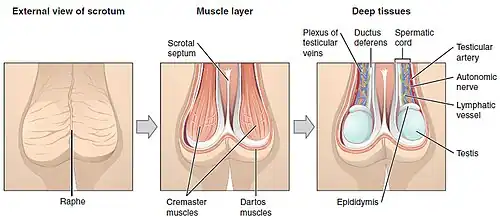

Diagram of the scrotum. On the left side the cavity of the tunica vaginalis has been opened; on the right side only the layers superficial to the cremaster muscle have been removed. | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Labioscrotal swelling |

| System | Reproductive system |

| Artery | Anterior scrotal artery, posterior scrotal artery |

| Vein | Testicular vein |

| Nerve | Posterior scrotal nerves, anterior scrotal nerves, genital branch of genitofemoral nerve, perineal branches of posterior femoral cutaneous nerve |

| Lymph | Superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | scrotum |

| MeSH | D012611 |

| TA98 | A09.4.03.001 A09.4.03.004 |

| TA2 | 3693 |

| FMA | 18252 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

In most terrestrial mammals, the scrotum (pl.: scrotums or scrota; possibly from Latin scortum, meaning "hide" or "skin")[1][2] or scrotal sac is a part of the external male genitalia located at the base of the penis that consists of a suspended dual-chambered sac of skin and smooth muscle. The scrotum contains the external spermatic fascia, testicles, epididymis, and ductus deferens. It is a distention of the perineum and carries some abdominal tissues into its cavity including the testicular artery, testicular vein, and pampiniform plexus. The perineal raphe is a small, vertical, slightly raised ridge of scrotal skin under which is found the scrotal septum. It appears as a thin longitudinal line that runs front to back over the entire scrotum. In humans, the scrotum becomes covered with pubic hair at puberty. The scrotum will usually tighten during penile erection and when exposed to cold temperatures. One testis is typically lower than the other to avoid compression in the event of an impact.[3]

The scrotum is biologically homologous to the labia majora in females.

Structure

Nerve supply

| Nerve | Surface[4] |

|---|---|

| Genital branch of genitofemoral nerve | anterolateral |

| Anterior scrotal nerves (from ilioinguinal nerve) | anterior |

| Posterior scrotal nerves (from perineal nerve) | posterior |

| perineal branches of posterior femoral cutaneous nerve | inferior |

Blood supply

| Blood vessels[5] | |

|---|---|

| Anterior scrotal artery | originates from the deep external pudendal artery[6] |

| Posterior scrotal artery | |

| Testicular artery | |

Skin and glands

The skin on the scrotum is more highly pigmented in comparison to the rest of the body. The septum is a connective tissue membrane dividing the scrotum into two cavities.[7]

Lymphatic system

The scrotum lymph initially drains into the superficial inguinal lymph nodes, this then drains into the deep inguinal lymph nodes. The deep inguinal lymph nodes channel into the common iliac which ultimately releases lymph into the cisterna chyli.

| Lymphatic vessels[8] | |

|---|---|

| Superficial inguinal lymph nodes | |

| Popliteal lymph nodes | |

Asymmetry

One testis is typically lower than the other, which is believed to function to avoid compression in the event of impact; in humans, the left testis is typically lower than the right.[3] An alternative view is that testis descent asymmetry evolved to enable more effective cooling of the testicles.[9]

Internal structure

Additional tissues and organs reside inside the scrotum and are described in more detail in the following articles:

- Appendix of epididymidis

- Cavity of tunical albuginea

- Cremaster muscle

- Dartos fascia

- Efferent ductules

- Epididymis

- Leydig cell

- Lobule of testes

- Paradidymis

- Rete testes

- Scrotal septum

- Seminiferous tubule

- Sertoli cell

- Spermatic cord

- Testes

- Tunica albuginea of testis

- Tunica vaginalis parietal layer

- Tunica vaginalis visceral layer

- Tunica vasculosa testis

- Vas deferens

Development

Genital homology between sexes

Male sex hormones are secreted by the testes later in embryonic life to cause the development of secondary sex organs. The scrotum is developmentally homologous to the labia majora. The raphe does not exist in females. Reproductive organs and tissues develop in females and males begin during the fifth week after fertilization. The genital ridge grows behind the peritoneal membrane. By the sixth week, string-like tissues called primary sex cords form within the enlarging genital ridge. Externally, a swelling called the genital tubercule appears over the cloacal membrane.

Up until the eighth week after fertilization, the reproductive organs do not appear to be different between the male and female and are called in-differentiated. Testosterone secretion starts during week eight, reaches peak levels during week 13 and eventually declines to very low levels by the end of the second trimester. The testosterone causes the masculinization of the labioscrotal folds into the scrotum. The scrotal raphe is formed when the embryonic, urethral groove closes by week 12.[10]

Scrotal growth and puberty

Though the testes and scrotum form early in embryonic life, sexual maturation begins upon entering puberty. The increased secretion of testosterone causes the darkening of the skin and development of pubic hair on the scrotum.[11]

Function

The scrotum regulates the temperature of the testicles and maintains it at 35 degrees Celsius (95 degrees Fahrenheit), i.e. two or three degrees below the body temperature of 37 degrees Celsius (99 degrees Fahrenheit). Higher temperatures affect spermatogenesis.[12] Temperature control is accomplished by the smooth muscles of the scrotum moving the testicles either closer to or further away from the abdomen dependent upon the ambient temperature. This is accomplished by the cremaster muscle in the abdomen and the dartos fascia (muscular tissue under the skin that makes the scrotum appear wrinkly).[11]

Having the scrotum and testicles situated outside the abdominal cavity may provide additional advantages. The external scrotum is not affected by abdominal pressure. This may prevent the emptying of the testes before the sperm were matured sufficiently for fertilization.[12] Another advantage is it protects the testes from jolts and compressions associated with an active lifestyle. The scrotum may provide some friction during intercourse, helping to enhance the activity.[13]

Other animals

A scrotum is present in many land mammals with the exception of those with internal testicles (elephants and marsupial moles), while the testicles remain in the body cavity in all other vertebrates, including cloacal animals.[14] Unlike placental mammals, some male marsupials have a scrotum that is anterior to the penis,[15][16][17][18] which is not homologous to the scrotum of placental mammals,[19] although there are several marsupial species without an external scrotum.[20]

The external scrotum is also absent in fusiform marine mammals, such as whales and seals,[21] as well as in some lineages of land mammals, such as the afrotherians, xenarthrans, and numerous families of bats, rodents, and insectivores.[22][23]

Clinical significance

A study has indicated that use of a laptop computer positioned on the lap can negatively affect sperm production.[24][25]

Diseases and conditions

The scrotum and its contents can develop many diseases and can incur injuries. These include:

- Candidiasis (yeast infection)

- sebaceous cyst

- epidermal cyst

- hydrocele

- hematocele

- Molluscum contagiosum

- spermatocele

- Paget's disease of the scrotum[26]

- varicocele

- inguinal hernia

- epididymo-orchitis

- testicular torsion

- genital warts

- testicular cancer

- dermatitis

- undescended testes

- Chyloderma

- mumps

- scabies

- herpes

- pubic lice

- Chancroid (Haemophilus ducreyi)

- Chlamydia (Chlamydia trachomatis)

- Gonorrhea (Neisseria gonorrhoeae)

- Granuloma inguinale or (Klebsiella granulomatis)

- Syphilis (Treponema pallidum)

- scrotum eczema

- scrotal psoriasis disease

- Riboflavin deficiency

- Chimney sweeps' carcinoma

See also

- Retroperitoneal lymph node dissection

- Scrotal infusion, a temporary form of body modification

- Testicular self-examination

Bibliography

- Books

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1237 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 1237 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Van De Graaff, Kent M.; Fox, Stuart Ira (1989). Concepts of Human Anatomy and Physiology. Dubuque, Iowa: William C. Brown Publishers. ISBN 978-0697056757.

- Elson, Lawrence; Kapit, Wynn (1977). The Anatomy Coloring Book. New York, New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0064539142.

- "Gross Anatomy Image". Medical Gross Anatomy Atlas Images. University of Michigan Medical School. 1997. Retrieved 2015-02-23.

- Berkow, Robert (1977). The Merck Manual of Medical Information; Home Edition. Whitehouse Station, New Jersey: Merck Research Laboratories. ISBN 978-0911910872.

References

- ↑ van Driel, Mels (2010). Manhood: The Rise and Fall of the Penis. Reaktion Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-86189-708-4. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- ↑ Spiegl, Fritz (1996). Fritz Spiegl's Sick Notes: An Alphabetical Browsing-Book of Derivatives, Abbreviations, Mnemonics and Slang for Amusement and Edification of Medics, Nurses, Patients and Hypochondriacs. Taylor & Francis. p. 142. ISBN 978-1-85070-627-4. Retrieved October 14, 2023.

- 1 2 Bogaert, Anthony F. (1997). "Genital asymmetry in men" (PDF). Human Reproduction. 12 (1): 68–72. doi:10.1093/humrep/12.1.68. PMID 9043905. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-05-28. Retrieved 2015-06-29.

- ↑ Moore, Keith; Anne Agur (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy, Third Edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8.

- ↑ Elson & Kapit 1977.

- ↑ antthigh at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- ↑ "Scrotum". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- ↑ "VIII. The Lymphatic System. 5. The Lymphatics of the Lower Extremity. Gray, Henry. 1918. Anatomy of the Human Body". Retrieved 2015-02-24.

- ↑ Gallup, Gordon G.; Finn, Mary M.; Sammis, Becky (2009). "On the Origin of Descended Scrotal Testicles: The Activation Hypothesis". Evolutionary Psychology. 7 (4): 147470490900700. doi:10.1177/147470490900700402.

- ↑ Van De Graaff & Fox 1989, pp. 927–931.

- 1 2 Van De Graaff & Fox 1989, p. 935.

- 1 2 Van De Graaff & Fox 1989, p. 936.

- ↑ Jones, Richard (2013). Human Reproductive Biology. Academic Press. p. 74. ISBN 9780123821850.

The rear-entry position of mating may allow the scrotum to stimulate the clitoris and, in this way, may produce an orgasm ...

- ↑ "Science : Bumpy lifestyle led to external testes - 17 August 1996 - New Scientist". New Scientist. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- ↑ Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe; Marilyn Renfree (30 January 1987). Reproductive Physiology of Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33792-2.

- ↑ Libbie Henrietta Hyman (15 September 1992). Hyman's Comparative Vertebrate Anatomy. University of Chicago Press. pp. 583–. ISBN 978-0-226-87013-7.

- ↑ Menna Jones; Chris R. Dickman; Michael Archer (2003). Predators with Pouches: The Biology of Carnivorous Marsupials. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-06634-2.

- ↑ Norman Saunders; Lyn Hinds (1997). Marsupial Biology: Recent Research, New Perspectives. UNSW Press. ISBN 978-0-86840-311-3.

- ↑ Patricia J. Armati; Chris R. Dickman; Ian D. Hume (17 August 2006). Marsupials. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45742-2.

- ↑ C. Hugh Tyndale-Biscoe (2005). Life of Marsupials. Csiro Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-06257-3.

- ↑ William F. Perrin; Bernd Würsig; J.G.M. Thewissen (26 February 2009). Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-08-091993-5.

- ↑ "Scrotum". National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 6 January 2011.

- ↑ Lovegrove, B. G. (2014). "Cool sperm: Why some placental mammals have a scrotum". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 27 (5): 801–814. doi:10.1111/jeb.12373. PMID 24735476. S2CID 24332311.

- ↑ "Laptops may damage male fertility". BBC News. 2004-12-09. Retrieved 2012-01-30.

- ↑ Sheynkin, Yefim; et al. (February 2005). "Increase in scrotal temperature in laptop computer users". Hum. Reprod. 20 (2): 452–455. doi:10.1093/humrep/deh616. PMID 15591087.

- ↑ "Paget's disease of the scrotum Symptoms, Diagnosis, Treatments and Causes". RightDiagnosis.com. Retrieved 2015-02-24.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)