Scythians | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 9th-8th century BC–c. 3rd century BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

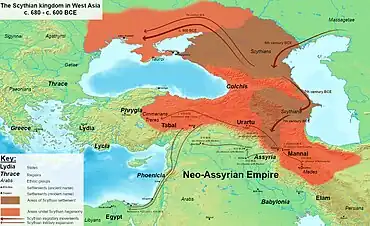

Maximum extent of the Scythian kingdom in West Asia (680-600 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Maximum extent of the Scythian kingdom in the Pontic steppe (600-c. 200 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Central Asia (9th-7th centuries BC) West Asia (7th–6th centuries BC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kamianka (from c. 6th century BC - c. 200 BC) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Scythian Akkadian (in West Asia) Thracian (in Pontic Steppe) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Scythian religion

Ancient Mesopotamian religion (in West Asia) Thracian religion (in Pontic Steppe) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Scythians | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• unknown-679 BC | Išpakaia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• 679-c. 659/8 BC | Bartatua | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 659/8-625 BC | Madyes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 610 BC | Spargapeithes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 600 BC | Lykos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 575 BC | Gnouros | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 550 BC | Saulius | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 530-510 BC | Idanthyrsus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 430 BC | Scyles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 490-460 BC | Ariapeithes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 460-450 BC | Octamasadas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 360s-339 BC | Ateas | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• c. 310 BC | Agaros | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dependency of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (from c. 672 to c. 625 BC) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age:

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Scythian migration from Central Asia to Caucasian Steppe | c. 9th-8th century BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Scythian alliance with the Neo-Assyrian Empire | c. 672 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Scythian conquest of Media | c. 652 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Scythian defeat of Cimmerians | c. 630s BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Median revolt against Scythians | c. 625 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 620 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 614-612 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Expulsion of Scythians from West Asia by Medes | c. 600 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 513 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• War with Macedonia | 340-339 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| c. 4th century BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

• Sarmatian invasion of Scythia | c. 3rd century BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Ukraine, Russia, Moldova, Romania, Belarus, Bulgaria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

The Scythians (/ˈsɪθiən/ or /ˈsɪðiən/) or Scyths (/ˈsɪθ/, but note Scytho- (/ˈsaɪθʊ/) in composition) and sometimes also referred to as the Pontic Scythians,[3][4] were an ancient Eastern Iranic[5] equestrian nomadic people who had migrated during the 9th to 8th centuries BC from Central Asia to the Pontic Steppe in modern-day Ukraine and Southern Russia, where they remained established from the 7th century BC until the 3rd century BC.

Skilled in mounted warfare,[6] the Scythians replaced the Agathyrsi and the Cimmerians as the dominant power on the western Eurasian Steppe in the 8th century BC.[7] In the 7th century BC, the Scythians crossed the Caucasus Mountains and frequently raided West Asia along with the Cimmerians.[7][8]

After being expelled from West Asia by the Medes, the Scythians retreated back into the Pontic Steppe and were gradually conquered by the Sarmatians.[9] In the late 2nd century BC, the capital of the largely Hellenized Scythians at Scythian Neapolis in the Crimea was captured by Mithridates VI and their territories incorporated into the Bosporan Kingdom.[10]

By the 3rd century AD, the Sarmatians and last remnants of the Scythians were overwhelmed by the Goths, and by the early Middle Ages, the Scythians and the Sarmatians had been largely assimilated and absorbed by early Slavs.[11][12] The Scythians were instrumental in the ethnogenesis of the Ossetians, who are believed to be descended from the Alans.[13]

After the Scythians' disappearance, authors of the ancient, mediaeval, and early modern periods used the name "Scythian" to refer to various populations of the steppes unrelated to them.[14]

The Scythians played an important part in the Silk Road, a vast trade network connecting Greece, Persia, India and China, perhaps contributing to the prosperity of those civilisations.[15] Settled metalworkers made portable decorative objects for the Scythians, forming a history of Scythian metalworking. These objects survive mainly in metal, forming a distinctive Scythian art.[16]

Names

Etymology

The English name Scythians or Scyths is derived from the Ancient Greek name Skuthēs (Σκυθης) and Skuthoi (Σκυθοι), derived from the Scythian endonym Skuδatā, meaning "archers."[1][17][2][18] Due to a sound change from /δ/ to /l/ in the Scythian language, evolved into the form *Skulatā.[1][2] This designation was recorded in Greek as Skōlotoi (Σκωλοτοι), which, according to Herodotus of Halicarnassus, was the self-designation of the tribe of the Royal Scythians.[18]

The Assyrians rendered the name of the Scythians as Iškuzaya (𒅖𒆪𒍝𒀀𒀀), māt Iškuzaya (𒆳𒅖𒆪𒍝𒀀𒀀), and awīlū Iškuzaya (𒇽𒅖𒆪𒍝𒀀𒀀),[19][20] or ālu Asguzaya (𒌷𒊍𒄖𒍝𒀀𒀀), māt Askuzaya (𒆳𒊍𒆪𒍝𒀀𒀀), and māt Ašguzaya (𒆳𒀾𒄖𒍝𒀀𒀀).[19][21]

The ancient Persians meanwhile called the Scythians "Sakā who live beyond the (Black) Sea" (𐎿𐎣𐎠 𐏐 𐎫𐎹𐎡𐎹 𐏐 𐎱𐎼𐎭𐎼𐎹, romanized: Sakā tayaiy paradraya) in Old Persian and simply Sakā (Ancient Egyptian: 𓋴𓎝𓎡𓈉, romanized: sk; 𓐠𓎼𓈉, romanized: sꜣg) in Ancient Egyptian, from which was derived the Graeco-Roman name Sacae (Ancient Greek: Σακαι; Latin: Sacae).[22][23]

Modern terminology

The Scythians were part of the wider Scytho-Siberian world, stretching across the Eurasian Steppes[18][24] of Kazakhstan, the Russian steppes of the Siberian, Ural, Volga and Southern regions, and eastern Ukraine.[25] In a broader sense, Scythians has also been used to designate all early Eurasian nomads,[24] although the validity of such terminology is controversial,[18] and other terms such as "Early nomadic" have been deemed preferable.[26]

Although the Scythians, Saka and Cimmerians were closely related nomadic Iranic peoples, and the ancient Babylonians, ancient Persians and ancient Greeks respectively used the names "Cimmerian," "Saka," and "Scythian" for all the steppe nomads, and early modern historians such as Edward Gibbon used the term Scythian to refer to a variety of nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples across the Eurasian Steppe,[27]

.png.webp)

- the name "Scythian" in contemporary modern scholarship generally refers to the nomadic Iranic people who from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC dominated the steppe and forest-steppe zones to the north of the Black Sea, Crimea, the Kuban valley, as well as the Taman and Kerch peninsulas,[32][23]

- while the name "Saka" is used specifically for their eastern members who inhabited the northern and eastern Eurasian Steppe and the Tarim Basin;[23][33][34][35]

- and while the Cimmerians were often described by contemporaries as culturally Scythian, they formed a different tribe from the Scythians proper, to whom the Cimmerians were related, and who also displaced and replaced the Cimmerians in the Pontic Steppe.[36]

The Scythians share several cultural similarities with other populations living to their east, in particular similar weapons, horse gear and Scythian art, which has been referred to as the Scythian triad.[18][26] Cultures sharing these characteristics have often been referred to as Scythian cultures, and its peoples called Scythians.[24][37] Peoples associated with Scythian cultures include not only the Scythians themselves, who were a distinct ethnic group,[38] but also Cimmerians, Massagetae, Saka, Sarmatians and various obscure peoples of the East European Forest Steppe,[18][24] such as early Slavs, Balts and Finno-Ugric peoples.[39][40]

Within this broad definition of the term Scythian, the westernmost Scythians have often been distinguished from other groups through the terms Classical Scythians, Western Scythians, European Scythians or Pontic Scythians.[24] Nevertheless, the archaeologist Maurits Nanning van Loon in 1966 instead used the term Western Scythians to designate the Cimmerians and referred to the Scythians proper as the Eastern Scythians.[41]

Scythologist Askold Ivantchik notes with dismay that the term "Scythian" has been used within both a broad and a narrow context, leading to a good deal of confusion. He reserves the term "Scythian" for the Iranic people dominating the Pontic Steppe from the 7th century BC to the 3rd century BC.[18] Nicola Di Cosmo writes that the broad concept of "Scythian" to describe the early nomadic populations of the Eurasian Steppe is "too broad to be viable," and that the term "early nomadic" is preferable.[26]

Location

Early phase in the western steppes

The earliest Scythian groups and Scythian culture are thought to have emerged with the Early Sakas from eastern Eurasia in the early 1st millennium BC.[42] After migrating out of Central Asia and into the western steppes, the Scythians first settled and established their kingdom in the area between the Araxes, the Caucasus Mountains and the Lake Maeotis.[43][44][45][46][47]

In West Asia

In West Asia, the Scythians initially settled in the area between the Araxes and Kura rivers before further expanding into the region to the south of the Kuros river in what is present-day Azerbaijan, where they settled around what is today Mingəçevir, Gəncə and the Muğan plain, and Transcaucasia remained their centre of operations in West Asia until the early 6th century BC,[48][49][50] although this presence in West Asia remained an extension of the Scythian kingdom of the steppes,[18] and the Scythian kings' headquarters were instead located in the Ciscaucasian steppes.[45][46]

During the peak of the Scythians' power in West Asia after they had conquered Media, Mannai and Urartu and defeated the Cimmerians, the Scythian kingdom's possessions in the region consisted of a large area extending from the Halys river in Anatolia in the west to the Caspian Sea and the western borders of Media in the east, and from Transcaucasia in the north to the northern borders of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the south.[51][52][53]

In the Pontic steppe

The territory of the Scythian kingdom of the Pontic steppe extended from the Don river in the east to the Danube river in the west, and covered the territory of the treeless steppe immediately north of the Black Sea's coastline, which was inhabited by nomadic pastoralists, as well as the fertile black-earth forest-steppe area to the north of the treeless steppe, which was inhabited by an agricultural population,[55][47][56][57] and the northern border of this Scythian kingdom were the dedicuous woodlands.[58]

Several rivers flowed southwards across this region and emptied themselves into the Black Sea, of which the largest one was the Borysthenes (Dnipro), which was the richest river in Scythia, with most of the fish living in it, and the best pastures and most fertile lands being located on its banks, while its water was the cleanest; due to this, Graeco-Roman authors compared it to the Nile in Egypt. Other important rivers of Scythia were the:[58][59]

- Istros (Danube),

- Tyras (Dnister),

- Hypanis (Southern Buh),

- Panticapes (Inhulets),

- Hypacyris,

- Gerrhus,

- and Tanais (Don).

The region within the Scythian Pontic realm which was covered with forests was named by the Greeks as the country of Hylaea (Ancient Greek: Υλαια, romanized: Hulaia, lit. 'the Woodland'), and consisted of the region of the lower Dnipro river along the territory of what is modern-day Kherson.[60][61]

Earlier ancient West Asian and Greek sources also included Ciscaucasia within the confines of Scythia. However, Ciscaucasia was no longer part of Scythia by the 5th century BC, and the Don river formed its easternmost limit.[62]

Little Scythia

After the 3rd century BC, Scythian territory because restricted to two small states, each called "Little Scythia," respectively located in Dobruja and Crimea:

- in Dobruja, the Scythian kingdom's territory stretched from Tyras, or even Pontic Olbia in the north, to Odessus in the south;[63]

- in Crimea, the Scythian kingdom covered a limited a territory which included the steppes and foothills of Crimea from contemporary Taurida, the lower Dnieper River, and the lower Southern Bug rivers.[47]

History

Because the Scythians did not use writing and they did not leave much material remains due to their nomadic lifestyle, most of the information regarding them has been pieced from the accounts of outsiders such as the Assyrians, Persians, and Greeks, as well as from archaeological study of their burial mounds.[65]

Origins

Based on initial archaeological evidence, it was generally agreed that the Scythians originated in the region of the Volga-Ural steppes of western Central Asia, possibly around the 9th century BC,[63] as a section of the population of the Srubnaya culture[47][66] containing a significant element originating from the Siberian Andronovo culture.[67] The population of the Srubnaya culture was among the first truly nomadic pastoralist groups, who themselves emerged in the Central Asian and Siberian steppes during the 9th century BC as a result of the cold and dry climate then prevailing in these regions.[58]

Based on more recent archaeological evidence, eastern Central Asia and the Altaian region is now favored as initial place of origin of the Scythian material culture, which later would have been mediated westwards, paired with at least some demic-diffusion via Saka-like groups. The Saka themself arose from admixture between earlier Eastern Iranian peoples with local Siberian groups. As such, the emergence of Scythian cultures is not a direct continuation of the Bronze Age Srubnaya culture, but a later development.[68]

Genetic evidence has suggested that Western Scythians may have been closely related to the Srubnaya culture, however, this does not imply direct continuity from Srubnaya, and the Western Scythians themselves derived ancestry from other populations as well.[24][69][70]

Early history

During the 9th to 8th centuries BC, a significant movement of the nomadic peoples of the Eurasian Steppe started when another nomadic Iranic tribe closely related to the Scythians from eastern Central Asia, either the Massagetae[45] or the Issedones,[71] migrated westwards, forcing the early Scythians to the west across the Araxes river,[72] following which some Scythian tribes had migrated westwards into the steppe adjacent to the shores of the Black Sea, which they occupied along with the Cimmerians, who were also a nomadic Iranic people closely related to the Scythians.[47]

Arrowheads from the 1st kurgan of the Arzhan burials suggests that the typical Scythian socketed arrows made of copper alloy might have originated during this period.[73][74]

Over the course of the 8th and 7th centuries BC, the Scythians migrated into the Caucasian and Caspian Steppes in several waves, becoming the dominant population of the region,[45] where they assimilated most of the Cimmerians and conquered their territory,[47] with this absorption of the Cimmerians by the Scythians being facilitated by their similar ethnic backgrounds and lifestyles,[75] after which the Scythians settled in the area between the Araxes, the Caucasus, and the Lake Maeotis.[72][44][47][45][46]

Archaeologically, the westwards migration of the Early Scythians from Central Asia into the Caspian Steppe constituted the latest of the two to three waves of expansion of the Srubnaya culture to the west of the Volga. The last and third wave corresponding to the Scythian migration has been dated to the 9th century BC.[76] The Scythians were already skilled at goldsmithing at these early dates.[77]

Materially, the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk culture with which the Cimmerians are associated showed strong influences originating from the east in Central Asia and Siberia (more specifically from the Karasuk, Arzhan, and Altai cultures), as well as from the Kuban culture of the Caucasus which contributed to its development,[45] thus making it difficult to distinguish from the Late Srubnaya culture of the early Scythians who became dominant in the Pontic steppe and replaced the Cimmerians in the Caucasian steppe, with both the Cimmerians and the Scythians being part of the larger Chernagorovsk-Arzhan cultural complex,[78] and both Scythians and the Cimmerians used Novocherkassk objects when the Scythians initially arrived into the Caucasian and Pontic steppes.[75] The transition from the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk culture to the Scythian culture appears to have itself been a continuous process,[78] and the Cimmerians cannot be distinguished from the Scythians during the period of transition from the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk culture to the Scythian culture.[79]

During this early migratory period, some groups of Scythians settled in Ciscaucasia and the Caucasus Mountains' foothills to the east of the Kuban river, where they settled among the native populations of this region, and did not migrate to the south into West Asia.[80]

Arrival into West Asia

.jpg.webp)

Under Scythian pressure, the displaced Cimmerians migrated to the south along the coast of the Black Sea and reached Anatolia, and the Scythians in turn later expanded to the south, following the coast of the Caspian Sea and arrived in the Ciscaucasian steppes, from where they settled in the area between the Araxes and Kura rivers before further expanding into the region to the south of the Kuros river in what is present-day Azerbaijan, where they settled around what is today Mingəçevir, Gəncə and the Muğan plain, and turned eastern Transcaucasia into their centre of operations in West Asia until the early 6th century BC,[48][49][50][47][80][51][81] with this presence in West Asia being an extension of the Scythian kingdom of the steppes.[18]

The earliest Scythians had belonged to the Srubnaya culture, and, archaeologically, the Scythian movement into Transcaucasia is attested in the form of a migration of a section of the Srubnaya culture, called the Srubnaya-Khvalynsk culture, to the south till the northern foothills of the Caucasus Mountains, and then further south along the western coast of the Caspian Sea into Transcaucasia and Iran.[67][47][82]

Although the Early Scythians initially belonged to a pre-Scythian archaeological culture of Central Asian origin,[83][18] their original Srubnaya culture, which contained significant admixture from the Andronovo culture, evolved into the Scythian culture from coming in contact with the peoples of Transcaucasia and the Urartians,[67] and further contacts with the civilisation of West Asia, and especially with that of Mesopotamia, would also have an important influence on the formation of Scythian culture.[45][46] The Scythians were still a Bronze Age society until the late 8th century BC, and it was only when they expanded into West Asia that they became acquainted with iron smelting and forging.[84]

During this period, the Scythian kings' headquarters were located in the Ciscaucasian steppes, and this presence in Transcaucasia influenced Scythian culture: the akīnakēs sword and socketed bronze arrowheads with three edges, which, although they are considered as typically "Scythian weapons," were in fact of Transcaucasian origin and had been adopted by the Scythians during their stay in the Caucasus.[85][80] Alternatively, the typical Scythian arrowheads might have originated in Siberia during the 9th century BC[73][74] and was introduced into West Asia by the Scythians.[73]

Arrival in the Pontic steppe

From their base in the Caucasian Steppe, during the period of the 8th to 7th centuries BC itself, the Scythians conquered the Pontic and Crimean Steppes to the north of the Black Sea up to the Danube river, which formed the western boundary of Scythian territory onwards,[63][45][63][86][87] with this process of Scythian takeover of the Pontic Steppe becoming fully complete by the 7th century BC.[88]

Archaeologically, the expansion of the Scythians into the Pontic Steppe is attested through the westward movement of the Srubnaya-Khvalynsk culture into Ukraine contemporaneous with its movement to the south along the coast of the Caspian Sea. The Srubnaya-Khvalynsk culture in Ukraine is referred to in scholarship as the "Late Srubnaya" culture.[82]

The westward migration of the Scythians was accompanied by the introduction into the north Pontic region of articles originating in the Siberian Karasuk culture, such as distinctive swords and daggers, and which were characteristic of Early Scythian archaeological culture, consisting of cast bronze cauldrons, daggers, swords, and horse harnesses,[46][89] which had themselves been influenced by Chinese art, with, for example, the "cruciform tubes" used to fix strap-crossings being of types which had initially been modelled by Shang artisans.[90]

The Scythian migration into the Pontic Steppe destroyed earlier cultures, with the settlements of the Sabatynivka culture in the Dnipro valley being largely destroyed around c. 800 BC, and the centre of Cimmerian bronze production ceasing to exist during the 8th to 7th centuries BC, around the time which the Chernogorovka-Novocherkassk culture was also disturbed. The migration of the Scythians affected the steppe and forest steppe areas of south-east Europe and forced several other populations of the region, especially many smaller groups, to migrate towards more remote regions,[63] including some North Caucasian groups who retreated to the west and settled in Transylvania and the Hungarian Plain where they introduced Novocherkassk culture type swords, daggers, horse harnesses, and other objects:[91] among these displaced smaller populations from the Caucasus were the Sigynnae, who were displaced westward into the eastern part of the Pannonian Basin.[92][93][45]

Among the many peoples displaced by the Scythian expansion were also the Gelonians and the Agathyrsi, the latter of whom were another nomadic Iranic people related to the Scythians as well as one of the oldest Iranic population[94] to have dominated the Pontic Steppe. The Agathyrsi were pushed westwards by the Scythians, away from the steppes and from their original home around Lake Maeotis,[45][94] after which the relations between the two populations remained hostile.[45] Within the Pontic steppe, some of the Scythian tribes intermarried with the already present native sedentary Thracian populations to form new tribes such as the Nomadic Scythians and the Alazones.[76]

In many parts of the north Pontic region under their rule, the Scythians established themselves as a ruling class over already present sedentary populations, including Thracians in the western regions, Maeotians on the eastern shore of Lake Maeotis, and later the Greeks on the north coast of the Black Sea.[18][95]

Between 650 and 625 BC, the Pontic Scythians came into contact with the Greeks, who were starting to create colonies in the areas under Scythian rule, including on the island of Borysthenes, near Taganrog on Lake Maeotis, as well as more places, including Panticapaeum, Pontic Olbia, and Phanagoria and Hermonassa on the Taman peninsula; the Greeks carried out thriving commercial ties with the sedentary peoples of the forest steppe who lived to the north of the Scythians, with the large rivers of eastern Europe which flowed into the Black Sea forming the main access routes to these northern markets. This process put the Scythians into permanent contact with the Greeks, and the relations between the latter and the Greek colonies remained peaceful, although the Scythians might have destroyed Panticapaeum at some point in the middle of the 6th century BC.[18][96] The territory around Pontic Olbia was under the direct rule of that city and was inhabited only by Greeks.[97]

Using the Pontic steppe as their base, the Scythians over the course of the 7th to 6th centuries BC often raided into the adjacent regions, with Central Europe being a frequent target of their raids, and Scythian incursions reaching Podolia, Transylvania, and the Hungarian Plain, due to which, beginning in this period, and from the end of the 7th century onwards, new objects, including weapons and horse-equipment, originating from the steppes and remains associated with the early Scythians started appearing within Central Europe, especially in the Thracian and Hungarian plains, and in the regions corresponding to present-day Bessarabia, Transylvania, Hungary, and Slovakia. Multiple fortified settlements of the Lusatian culture were destroyed by Scythian attacks during this period, with the Scythian onslaught causing the destruction of the Lusatian culture itself. Attacks by the Scythians were directed at southern Germania, and, from there, until as far as Gaul, and possibly even the Iberian Peninsula; these activities of the Scythians were not unlike those of the Huns and the Avars during the Migration Period and of the Mongols in the mediaeval era, and they were recorded in Etruscan bronze figurines depicting mounted Scythian archers as well as in Scythian influences in Celtic art.[45][63][99] Among the sites in Central Europe attacked by the Scythians was that of Smolenice-Molpír, where Scythian-type arrows were found at this fortified hillfort's access points at the gate and the south-west side of the acropolis[100]

The Scythians attacked, sacked and destroyed many of the wealthy and important Iron Age settlements[101] located to the north and south of the Moravian Gate and belonging to the eastern group of the Hallstatt culture, including that of Smolenice-Molpír,[100] leading to the adoption of the Scythian-type "Animal Style" art and mounted archery by the population of these regions in the subsequent period.[101][102] It was also at this time that the Scythians introduced metalwork types which followed Shang Chinese models into Western Eurasia, where they were adopted by the Hallstatt culture.[90]

As part of the Scythians' expansion into Europe, one section of the Scythian Sindi tribe migrated during the 7th to 6th centuries BC from the region of the Lake Maeotis towards the west, through Transylvania into the eastern Pannonian basin, where they settled alongside the Sigynnae and soon lost contact with the Scythians of the Pontic steppe.[45][99] Another section of the Sindi established themselves on the Taman peninsula, where they formed a ruling class over the indigenous Maeotians, the latter of whom were of native Caucasian origin.[46][96]

Presence in West Asia

During the earliest phase of their presence in West Asia, the Scythians under their king Išpakaia were allied with the Cimmerians,[47] and the two groups, in alliance with the Medes, who were an Iranic people of West Asia to whom the Scythians and Cimmerians were distantly related, as well as the Mannaeans, were threatening the eastern frontier of the kingdom of Urartu during the reign of its king Argishti II, who reigned from 714 to 680 BC.[105] Argishti II's successor, Rusa II, built several fortresses in the east of Urartu's territory, including that of Teishebaini, to monitor and repel attacks by the Cimmerians, the Mannaeans, the Medes, and the Scythians.[106]

The first mention of the Scythians in the records of the then superpower of West Asia, the Neo-Assyrian Empire, is from between 680/679 and 678/677 BC,[18] when their king Išpakaia joined an alliance with the Mannaeans[107] and the Cimmerians in an attack on the Neo-Assyrian Empire. During this time, the Scythians under Išpakaia, allied to Rusa II of Urartu, were raiding far in the south till the Assyrian province of Zamua. These allied forces were defeated by the Assyrian king Esarhaddon.[108][50]

The Mannaeans, in alliance with an eastern group of the Cimmerians who had migrated into the Iranic plateau and with the Scythians (the latter of whom attacked the borderlands of Assyria from across the territory of the kingdom of Ḫubuškia), were able to expand their territories at the expense of Assyria and capture the fortresses of Šarru-iqbi and Dūr-Ellil. Negotiations between the Assyrians and the Cimmerians appeared to have followed, according to which the Cimmerians promised not to interfere in the relations between Assyria and Mannai, although a Babylonian diviner in Assyrian service warned Esarhaddon not to trust either the Mannaeans or the Cimmerians and advised him to spy on both of them.[50] In 676 BC, Esarhaddon responded by carrying out a military campaign against Mannai during which he killed Išpakaia.[50] Išpakaia was succeeded by Bartatua, who might have been his son.[108]

In the later mid-670s BC, in alliance with the eastern Cimmerians, the Scythians were menacing the Assyrian provinces of Parsumaš and Bīt Ḫamban, and these joint Cimmerian-Scythian forces together were threatening communication between the Assyrian Empire and its vassal of Ḫubuškia.[109] The Mannaeans, eastern Cimmerians, and Medes soon joined a grand coalition headed by the Median chieftain Kashtariti.[110]

Bartatua and the alliance with Assyria

Išpakaia was succeeded by Bartatua, who might have been his son,[108] and with whom they had already started negotiations immediately after Išpakaia's death[50] and they had been able to defeat Kashtariti in the meantime in 674 BC, after which his coalition disintegrated.[108]

In 672 BC[18] Bartatua himself sought a rapprochement with the Assyrians and asked for the hand of Esarhaddon's daughter Šērūʾa-ēṭirat in marriage, which is attested in Esarhaddon's questions to the oracle of the Sun-god Šamaš. Whether this marriage did happen is not recorded in the Assyrian texts, but the close alliance between the Scythians and Assyria under the reigns of Bartatua and his son and successor Madyes suggests that the Assyrian priests did approve of this marriage between a daughter of an Assyrian king and a nomadic lord, which had never happened before in Assyrian history; thus, the Scythians were separated from the Medes and were brought into a marital alliance with Assyria, and Šērūʾa-ēṭirat was likely the mother of Bartatua's son Madyes.[50][47][108][106][111][112][73]

Bartatua's marriage to Šērūʾa-ēṭirat required that he would pledge allegiance to Assyria as a vassal, and in accordance to Assyrian law, the territories ruled by him would be his fief granted by the Assyrian king, which made the Scythian presence in West Asia a nominal extension of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and Bartatua himself an Assyrian viceroy. Under this arrangement, the power of the Scythians in West Asia heavily depended on their cooperation with the Assyrian Empire; henceforth, the Scythians remained allies of the Assyrian Empire,[46] with Bartatua helping the Assyrians by defeating the state of Mannai and imposing Scythian hegemony over it.[113] Around this time, the Urartian king Rusa II might also have enlisted Scythian troops to guard his western borderlands.[106]

The marital alliance between the Scythian king and the Assyrian ruling dynasty, as well as the proximity of the Scythians with the Assyrian-influenced Mannai and Urartu, thus placed the Scythians under the strong influence of Assyrian culture,[46] and contact with the civilisation of West Asia would have an important influence on the formation of Scythian culture.[45] Among the concepts initially foreign to the Scythians which they had adopted from the Mesopotamian and Transcaucasian peoples was that of the divine origin of royal power, as well as the practice of performing human sacrifices during royal funerals, and the Scythian kings henceforth imitated the style of rulership of the West Asian kings.[114][47]

West Asian influence on Scythians

The Scythians adopted many elements of the cultures of the populations of Urartu and Transcaucasia, especially of more effective weapons: the akīnakēs sword and socketed bronze arrowheads with three edges, which, although they are considered as typically "Scythian weapons," were in fact of Transcaucasian origin and had been adopted by the Scythians during their stay in the Caucasus.[85][80]

The art typical of the Scythians proper originated between 650 and 600 BC for the needs of the Royal Scythians at the time when they ruled over large swathes of West Asia, with the objects of the Ziwiye hoard being the first example of this art. Later examples of this West Asian-influenced art from the 6th century BC were found in western Ciscaucasia, as well as in the Melhuniv kurhan in what is presently Ukraine and in the Witaszkowo kurgan in what is modern-day Poland. This art style was initially restricted to the Scythian upper classes, and the Scythian lower classes in both West Asia and the Pontic steppe had not yet adopted it, with the latter group's bone cheek-pieces and bronze buckles being plain and without decorations, while the Pontic groups were still using Srubnaya- and Andronovo-type geometric patterns.[115]

Within the Scythian religion, the goddess Artimpasa and the Snake-Legged Goddess were significantly influenced by the Mesopotamian and Syro-Canaanite religions, and respectively absorbed elements from Astarte-Ishtar-Aphrodite for Artimpasa and from Atargatis-Derceto for the Snake-Legged Goddess.[116]

Conquest of Mannai

Over the course of 660 to 659 BC, Esarhaddon's son and successor to the Assyrian throne, Ashurbanipal, sent his general Nabû-šar-uṣur to carry out a military campaign against Mannai. After trying in vain to stop the Assyrian advance, the Mannaean king Aḫsēri was overthrown by a popular rebellion and was killed along with most of his dynasty by the revolting populace, after which his surviving son Ualli requested help from Assyria, which was provided through the intermediary of Ashurbanipal's relative, the Scythian king Bartatua, after which the Scythians extended their hegemony to Mannai itself.[113][108]

Around this same time, Bartatua's Scythians were also able to take over a significant section of the south-eastern territories of the state of Urartu.[108]

Madyes

Bartatua was succeeded by his son with Šērūʾa-ēṭirat, Madyes, who soon expanded the Scythian hegemony to the state of Urartu.[117][47][46]

Conquest of Media

When, following a period of Assyrian decline over the course of the 650s BC, Esarhaddon's other son, Šamaš-šuma-ukin, who had succeeded him as the king of Babylon, revolted against his brother Ashurbanipal in 652 BC, the Medes supported him, and Madyes helped Ashurbanipal suppress the revolt externally by invading the Medes. The Median king Phraortes was killed in battle, either against the Assyrians or against Madyes himself, who then imposed Scythian hegemony over the Medes for twenty-eight years on behalf of the Assyrians, thus starting a period which Greek authors called called the “Scythian rule over Asia,”[117][51][47][46] with Media, Mannai, and Urartu all continuing to exist as kingdoms under Scythian suzerainty.[117]

During this period, the Medes adopted Scythian archery techniques and equipment due to their superiority over those of the West Asian peoples,[50] and the trade of silk to western Eurasia might have started at this time through the intermediary of the Scythians during their stay in West Asia, with the earliest presence of silk in this part of the world having been found in a Urartian fortress, presumably imported from China through the intermediary of the Scythians.[106]

Defeat of the Cimmerians

During the 7th century BC, the bulk of Cimmerians were operating in Anatolia, where they constituted a threat against the Scythians’ Assyrian allies, who since 669 BC were ruled by Madyes's uncle, that is Esarhaddon's son and Šērūʾa-ēṭirat's brother, Ashurbanipal. Assyrian records in 657 BC might have referred to a threat against or a conquest of the western possessions of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in Syria,[118][119] and these Cimmerian aggressions worried Ashurbanipal about the security of his empire's north-west border.[120]

By 657 BC the Assyrian divinatory records were calling the Cimmerian king Tugdammi by the title of šar-kiššati ("King of the Universe"), which could normally belong only to the Neo-Assyrian King: thus, Tugdammi's successes against Assyria meant that he had become recognised in ancient West Asia as equally powerful as Ashurbanipal, and the kingship over the Universe, which rightfully belonged to the Assyrian king, had been usurped by the Cimmerians and had to be won back by Assyria. This situation continued throughout the rest of the 650s BC and the early 640s BC.[118]

In 644 BC, the Cimmerians, led by Tugdammi, attacked the kingdom of Lydia, defeated the Lydians and captured the Lydian capital, Sardis; the Lydian king Gyges died during this attack.[121][120][122] After sacking Sardis, Tugdammi led the Cimmerians into invading the Greek city-states of Ionia and Aeolis on the western coast of Anatolia.[118]

After this attack on Lydia and the Asian Greek cities, around 640 BC the Cimmerians moved to Cilicia on the north-west border of the Neo-Assyrian empire, where, after Tugdammi faced a revolt against himself, he allied with Assyria and acknowledged Assyrian overlordship, and sent tribute to Ashurbanipal, to whom he swore an oath. Tugdammi soon broke this oath and attacked the Neo-Assyrian Empire again, but he fell ill and died in 640 BC, and was succeeded by his son Sandakšatru.[121][120]

In 637 BC, the Thracian Treres tribe who had migrated across the Thracian Bosporus and invaded Anatolia,[123] under their king Kōbos and in alliance with Sandakšatru's Cimmerians and the Lycians, attacked Lydia during the seventh year of the reign of Gyges's son Ardys.[121] They defeated the Lydians and captured their capital of Sardis except for its citadel, and Ardys might have been killed in this attack.[124] Ardys's son and successor, Sadyattes, might possibly also have been killed in another Cimmerian attack on Lydia in 635 BC.[124]

Soon after 635 BC, with Assyrian approval[125] and in alliance with the Lydians,[126] the Scythians under Madyes entered Anatolia, expelled the Treres from Asia Minor, and defeated the Cimmerians so that they no longer constituted a threat again, following which the Scythians extended their domination to Central Anatolia.[51][121]

This final defeat of the Cimmerians was carried out by the joint forces of Madyes, whom Strabo credits with expelling the Treres and Cimmerians from Asia Minor, and of the son of Sadyattes and the great-grandson of Gyges, the Lydian king Alyattes, whom Herodotus of Halicarnassus and Polyaenus claim finally defeated the Cimmerians.[118][127] In Polyaenus' account of the defeat of the Cimmerians, he claimed that Alyattes used "war dogs" to expel them from Asia Minor, with the term "war dogs" being a Greek folkloric reinterpretation of young Scythian warriors who, following the Indo-European passage rite of the kóryos, would ritually take on the role of wolf- or dog-warriors.[128]

Scythian power in West Asia thus reached its peak under Madyes, with the territories ruled by the Scythians extending from the Halys river in Anatolia in the west to the Caspian Sea and the eastern borders of Media in the east, and from Transcaucasia in the north to the northern borders of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in the south.[52][51][53]

A Scythian group might have left Media and migrated into the region between the Don and Volga rivers, near the Sea of Azov in the North Caucasus, during this period in the 7th century BC, after which they merged with Maeotians who had a matriarchal culture and formed the Sauromatian tribe.[45]

Decline

Revolt of Media

By the 620s BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire began unravelling after the death of Ashurbanipal in 631 BC: in addition to internal instability within Assyria itself, Babylon revolted against the Assyrians in 626 BC under the leadership of Nabopolassar;[113] and the next year, in 625 BC, Cyaxares, the son of Phraortes and his successor to the Median kingship, overthrew the Scythian yoke over the Medes by inviting the Scythian rulers to a banquet and then murdering them all, including Madyes, after getting them drunk.[129][130][131][47][108]

Raid till Egypt

Shortly after Madyes's assassination, some time between 623 and 616 BC, the Scythians took advantage of the power vacuum created by the crumbling of the power of their former Assyrian allies and overran the Levant.[18][132]

This Scythian raid into the Levant reached as far south as Palestine, and was foretold by the Judahite prophets Jeremiah and Zephaniah as a pending "disaster from the north," which they believed would result in the destruction of Jerusalem,[108] but Jeremiah was discredited and in consequence temporarily stopped prophetising and lost favour with the Judahite king Josiah when the Scythian raid did not affect Jerusalem and or Judah.[108][133]

The Scythian expedition instead reached up to the borders of Egypt, where their advance was stopped by the marshes of the Nile Delta,[18][132] after which the pharaoh Psamtik I met them and convinced them to turn back by offering them gifts.[51][134]

The Scythians retreated by passing through the Philistine city of Ascalon largely without any incident, although some stragglers looted the temple of ʿAštart in the city,[135] which was considered to be the most ancient of all temples to that goddess, as a result of which the perpetrators of this sacrilege and their descendants were allegedly cursed by ʿAštart with a “female disease,” due to which they became a class of transvestite diviners called the Anarya (meaning “unmanly” in Scythian[18]).[51]

War against Assyria

According to Babylonian records, around 615 BC the Scythians were operating as allies of Cyaxares and the Medes in their war against Assyria, with the Scythians' abandonment of their alliance with Assyria to instead side with the Babylonians and the Medes being a critical factor in worsening the position of the Neo-Assyrian Empire,[136] and the Scythians participated in the Medo-Babylonian conquests of Aššur in 614 BC, Nineveh in 612 BC, and Ḫarran in 610 BC, which permanently destroyed the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[137][52][130]

The presence of Scythian-style arrowheads at locations where the Neo-Babylonian Empire is known to have conducted military campaigns, and which are associated with the destruction layers of these campaigns, suggests that certain contingents composed of Scythians or of Medes who had adopted Scythian archery techniques might have recruited by the Neo-Babylonian army during this war.[138]

These contingents participated in the battle of Carchemish in 605 BC,[138] while clay figurines depicting Scythian riders, as well as an Ionian shield and a Neo-Hittite battle-axe similar to those found in Scythian remains in the Pontic steppe, suggest that actual Scythian mercenaries had also participated at the final Neo-Babylonian victory over the Egyptians at Carchemish.[74]

The Scythian or Scythian-style contingents also participated in the Neo-Babylonian campaigns in the southern Levant, including in the Babylonian annexation of the kingdom of Judah in 586 BC.[138]

Expulsion from West Asia

_marble_with_red_paint_and_gold_leaf.jpg.webp)

The rise of the Medes and their empire allowed them to finally expel the Scythians from West Asia in the c. 600s BC,[139] after which, beginning in the later 7th and lasting throughout much of the 6th century BC, the majority of the Scythians migrated from Ciscaucasia into the Pontic Steppe, which became the centre of Scythian power.[114][108][45]

The inroads of the Cimmerians and the Scythians into West Asia over the course of the 8th to 6th centuries BC had destabilised the political balance which had prevailed in the region between the states of Assyria, Urartu, Mannaea and Elam on one side and the mountaineer and tribal peoples on the other, resulting in the destruction of these former kingdoms and their replacement by new powers, including the kingdoms of the Medes and of the Lydians.[50]

Some splinter Scythian groups nevertheless remained in West Asia, in the southeast Caucasus, and settled in Transcaucasia, especially the area corresponding to modern-day Azerbaijan[45] in eastern Transcaucasia,[46] due to which the area where they lived, and which corresponded to the core regions of the former West Asian Scythian realm, was called Sakašayana, meaning "land inhabited by the Saka (i.e. Scythians)," by the Medes after they had annexed this region to their empire.[140] The Median name for this territory was later recorded by Titus Livius under the form of Sacassani, and as Sakasēnē by Ptolemy, while the country was called the “Land of the Skythēnoi” by Xenophon.[80]

One such splinter group joined the Medes and participated in the Median conquest of Urartu, with Scythian arrowheads having been found in the destruction layers of the Urartian fortresses of Argištiḫinili and Teišebani, which were conquered by the Medes around c. 600 BC.[141][108] One group formed a kingdom in what is now Azerbaijan under Median overlordship, but eventually hostilities broke out between some of them and Cyaxares, due to which they left Transcaucasia and fled to Lydia.[142]

By the middle of the 6th century BC, the Scythians who had remained in West Asia had completely assimilated culturally and politically into Median society and no longer existed as a distinct group.[143]

Meanwhile, other Transcaucasian Scythian splinter groups later retreated northwards to join the West Asian Scythians who had already previously moved into the Kuban Steppe.[80]

Pontic Scythian kingdom

Early phase

After their expulsion from West Asia, and beginning in the later 7th and lasting throughout much of the 6th century BC, the majority of the Scythians, including the Royal Scythians, migrated into the Kuban Steppe in Ciscaucasia around 600 BC,[96] and from Ciscaucasia into the Pontic Steppe, which became the centre of Scythian power,[45] Although Herodotus of Halicarnassus claimed that the Scythians retreated into the northern Pontic region through Crimea, archaeological evidence instead suggests that the Royal Scythians migrated northwards into western Ciscaucasia,[145] and from there into the country of those Scythians who had previously established themselves in the Pontic steppe.[96][47]

Some of the Scythian groups who had settled in the eastern Pontic steppe to the east of the Dnipro river were displaced by the arrival of the Royal Scythians from West Asia, and they moved north into the region of the forest-steppe zone,[146] outside of the Pontic Scythian kingdom itself. These groups formed the tribes of the Androphagi, Budini, and Melanchlaeni.[145]

During this early phase of the Pontic Scythian kingdom, the hold of the Royal Scythians on the western part of the steppe located to the west of the Dnipro was light, and they were largely satisfied with the tribute they levied on the sedentary agriculturist population of the region. Meanwhile, the tribe of the Aroteres, which consisted of a settled Thracian population over which ruled an Iranic Scythian ruling class, imported Greek pottery, jewellery and weapons in exchange of agricultural products, and in turn offered them in tribute to their Scythian overlords.[147][97] However, the country of the Alazones tribe appears to have become poorer during this time, in the early 6th century BC, when many of the rebuilt pre-Scythian settlements in their territory were destroyed by the Royal Scythians arriving from West Asia.[56]

In Crimea, the Royal Scythians took over most of the territory up to the Cimmerian Bosporus in the east.[148] In western Ciscaucasia, where the Scythians were not large in number enough to spread throughout the region, they instead took over the steppe to the south of the Kuban river's middle course, where they reared large herds of horses.[96]

It was at this time[90] that the Scythians brought the knowledge of working iron which they had acquired in West Asia with them and introduced it into the Pontic Steppe, whose peoples were still Bronze Age societies until then.[84] Some West Asian blacksmiths might also have accompanied the Scythians during their nortwards retreat and become employed by Scythian kings, after which the practice of ironworking soon spread to the neighbouring populations.[84]

During this period, the tribe of the Royal Scythians would primarily bury their dead at the edges of the territories they occupied, especially in the western Cisaucasian region, instead of within the steppe region that was the centre of their kingdom; due to this, several Scythian kurgan nekropoleis were located in Ciscaucasia, with some of them being significantly wealthy and belonging to aristocrats or royalty, and the Royal Scythians' burials in the Kuban Steppe were the most lavish of all Scythian funerary monuments during the Early Scythian period.[149][18] [96] During the early 6th century BC, the some groups of Transcaucasian Scythians migrating northwards would arrive into the Pontic Steppe to reinforce the Royal Scythians who had already arrived there.[96]

Meanwhile, the Median, Lydian, Egyptian, and Neo-Babylonian empires that the Scythians had interacted with during their stay in West Asia were replaced at this time by the Persian Achaemenid Empire founded by the Persian Cyrus II. The Persians were an Iranic people just like the Scythians and the Medes, and, during the early phase of the Achaemenid empire, their society still preserved many archaic Iranic aspects which they had in common with the Scythians.[150] The formation of the Achaemenid empire appears to have pressured the Scythians into remaining to the north of the Black Sea.[139]

Soon after, during the Early Scythian period itself, the centre of power of the Royal Scythians shifted from the eastern Pontic steppe to the north-west, in the country of the Aroteres tribe, where was located the main industrial centre of Scythia:[147] and which corresponded to the country of Gerrhos, which was located in the eastern part of the country of the Aroteres, on the boundary of the steppe and the forest-steppe. During this period, the Royal Scythians buried their dead in the country of Gerrhos.[151]

At this time, there were close links between the new political centre of Scythia in Gerrhos and the Greek colony of Pontic Olbia, and members of the royal family often visited this city.[152]

During this period, the Scythians were ruled by a succession of kings whose names were recorded by Herodotus of Halicarnassus:[18]

- Spargapeithes

- Lykos, son of Spargapeithes

- Gnouros, son of Lykos

- Saulios, son of Gnouros

- Idanthyrsus, son of Saulios

At the time of Idanthyrsus, and possibly later, the Scythians were ruled by a triple monarchy, with Skōpasis and Taxakis ruling alongside Idanthyrsus.[18]

Scopasis was himself the king of the Sauromatians, who maintained peaceful relations with the Scythians, with a long road starting in Scythia and continuing towards the eastern regions of Asia existing thanks to these friendly relations.[153]

The Persian invasion

In 513 BC, the king Darius I of the Persian Achaemenid Empire carried out a campaign against the Pontic Scythians. In response, the Scythian king Idanthyrsus summoned the kings of the peoples surrounding his kingdom to a meeting to decide how to deal with the Persian invasion. The kings of the Budini, Gelonians, and Sarmatians agreed to help the Scythians against the Persian attack, while the kings of the Agathyrsi, Androphagi, Melanchlaeni, Neuri, and Tauri refused to support the Scythians.[155]

When the armies of the Scythians fled to the territories of their neighbours in front of the advancing Persian army, the Agathyrsi refused to provide refuge to the Scythians, which forced them to retreat back into their own territory.[156]

Darius's invasion was resisted by Idanthyrsus, Skōpasis, and Taxakis, with the Scythians refusing to fight an open battle against the well-organised Achaemenid army, and instead resorting to partisan warfare and goading the Persian army deep into Scythian territory. The Persian army might have crossed the Don river and reached the territory of the Sauromatians, where Darius built fortifications, but resumed their pursuit when the Scythian forces returned. The results of this campaign were also unclear, with the Persian inscriptions themselves referring to the Sakā tayaiy paradraya (the "Saka who dwell beyond the (Black) Sea"), that is to the Scythians, as having been conquered by Darius, while Greek authors instead claimed that Darius' campaign failed and from then onwards developed a tradition of idealising the Scythians as being invincible thanks to their nomadic lifestyle.[157][47][18]

Although the Scythians and the Persians were both Iranic peoples related to each other, the Greeks tended to perceive the Scythians as being "savage" nomads whom they associated with the Thracians, while they saw the Persians as a "civilised" sedentary people whom they associated with the Assyrians and Babylonians. Therefore, the ancient Greeks saw the Persian invasion of Scythia as a clash between "savagery" represented by the Scythians and "civilisation" represented by the Persians.[150]

Early decline

Over the course of the late 6th century BC, the Scythians had progressively lost their territories in the Kuban region to another nomadic Iranic people, the Sauromatians, beginning with the territory to the east of the Laba river, and then the whole Kuban territory. By the end of the 6th century BC, the Scythians had lost their territories in the Kuban Steppe and had been forced to retreat into the Pontic Steppe, except for its westernmost part which included the Taman peninsula, where the Scythian Sindi tribe formed a ruling class over the native Maeotians, due to which this country was named Sindica. By the 5th century BC, Sindica was the only place in the Caucasus where the Scythian culture survived.[96][158]

Expansion

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

After losing their territories in the Kuban Steppe in the late 6th century BC, the Scythians had been forced to fully retreat into the Pontic Steppe, and the Royal Scythians' centre of power within Scythia shifted to the south, in the region of the bend of the Dnipro, where the site of Kamianka became the principal industrial centre of Scythia, with the sedentary population of the city being largely metal-workers who smelted bog iron ores into iron that was made into tools, simple ornaments and weapons for the agricultural population of the Dnipro valley and of other regions of Scythia, and the city itself was the most prominent supplier of iron and bronze products to the nomadic Scythians; the city of Kamianka also became the capital of the Scythian kings, whose headquarters were located in the further fortified acropolis of the city. At the same time, a wave of Sauromatian nomads from the lower Volga steppe in the east immigrated into Scythia over the course of 550 and 500 BC and were absorbed by the Pontic Scythians with whom they mingled. A large number of settlements in the valleys of the steppe rivers were destroyed as a result of these various migratory movements.[159][160][161][47][46][18]

The retreat of the Scythians from the Kuban Steppe and the arrival of the Sauromatian immigrants into the Pontic steppe over the course of the late 6th to early 5th centuries BC caused significant material changes in the Scythian culture soon after the Persian campaign, changes which are not attributable to a normal autochthonous evolution. Some of the changes were derived from the Sauromatian culture of the Volga steppe, while others originated among the Kuban Scythians, thus resulting in the sudden appearance within the lower Dnipro region of a fully formed Scythian culture with no local forerunners, and which included a notable increase in the number of Scythian funerary monuments.[96][18]

The Scythians underwent tribal unification and political consolidation in reaction to the Persian invasion, and[18] the names of kings who ruled over the Scythians the 5th century BC are known, although it is unknown whether these kings were ruling only the western regions of Scythia located between the Danube and Pontic Olbia or over all the Scythians:[18]

- Ariapeithes

- Scyles, the son of Ariapeithes by a Greek woman from Histria

- Octamasadas, the son of Ariapeithes by the daughter of the Thracian Odrysian king Teres I. Octamasadas deposed Scyles and replaced him on the throne

The Scythians also became more active and aggressive around this time, possibly as a result of the arrival of the new Sauromatian nomadic elements from the east, or out of necessity to resist Persian expansionism. This change manifested itself through the consolidation of the dominant position of the Royal Scythians over the other tribes within Scythia and through the Royal Scythians' hold on the western part of their realm to the west of the Dnipro, where lived the agriculturist populations, becoming heavier and more oppressive, and the Scythians may also have gained access to the Wallachian and Moldavian plains at this time, although Oltenia and parts of Moldavia were instead occupied by the Agathyrsi. Another result of the changes within Scythia during this period was increased Scythian expansionism:[18][63][162] one of the target areas of Scythian expansionism was Thrace, where the Scythians seem to have established a permanent presence to the south of the Danube at an early point, with the Greek cities of Kallatis and Dionysupolis in the area corresponding to the present-day Dobruja both being surrounded by Scythian territory; and, in 496 or 495 BC, the Scythians raided the Thracian territories far to the south of the Danube till the Thracian Chersonese on the Hellespont, as an attempt to secure themselves from Persian encroachment.[47][63][18]

The emergence of the Thracian Odrysian kingdom during the 5th century BC soon blocked the Scythian advances in Thrace, and the Scythians established friendly contacts with the Odrysians, with the Danube river being set as the common border between the two kingdoms, and a daughter of the Odrysian founder king Tērēs I marrying the Scythian king Ariapeithes; these friendly relations also saw the Scythians and Thracians adopting aspects of each other's art and lifestyles.[47][63][18]

However, at some point in the 5th century BC, the Agathyrsian king Spargapeithes treacherously killed the Scythian king Ariapeithes.[155][163]

In the north and north-west, Scythian expansionism manifested itself through the destruction of the fortified settlements of the forest steppe and the subjugation of its population.[18]

In the south, the Scythians tried to impose their rule over the Greek colonies on the northern shores of the Black Sea: the Greek settlement of Kremnoi at Taganrog on the lower reaches of the Don river river, which was the only Greek colony in that area, had already been destroyed by the Scythians between 550 and 525 BC, and, owing to the Scythians' necessity to continue commerce with the Greeks, was replaced by a Scythian settlement at Yelizavetovskaya which became the principal trade station between the Greeks and the Scythians in this region.[18]

Although the relations between the Scythians and the Greek cities of the northern Pontic region had until then been largely peaceful and the cities previously had no defensive walls and possessed unfortified rural settlements in the area, new hostile relations developed between these two parties, and during the 490s BC fortifications were built in many Pontic Greek cities, whose khōrai were abandoned or destroyed, while burials of men killed by Scythian-type arrowheads appeared in their nekropoleis.[18] Between 450 and 400 BC, Kerkinitis was paying tribute to the Scythians.[18] The Scythians were eventually able to successfully impose their rule over the Greek colonies in the north-western Pontic shores and in western Crimea, including Niconium, Tyras, Pontic Olbia, and Kerkinitis,[63][18][97] and the close relations between Pontic Olbia and the Scythian political centre ended at this time.[152]

The hold of the Scythians over the western part of the Pontic region thus became firmer during the 5th century BC, with the Scythian king Scyles having a residence in the Greek city of Pontic Olbia which he would visit each year, while the city itself experienced a significant influx of Scythian inhabitants during this period, and the presence of coins of Scyles issued at Niconium in the Dnister valley attesting of his control over this latter city. This, in turn, allowed the Scythians to participate in indirect relations with the city of Athens in Greece proper, which had established contacts in Crimea.[63][18] The destruction of the Greek cities' khōrai and rural settlements however also meant that they lost their grain-producing hinterlands, with the result being that the Scythians instituted an economic policy under their control whereby the sedentary peoples of the forest steppe to their north became the primary producers of grain, which was then transported through the Southern Buh and Dnipro rivers to the Greek cities to their south such as Tyras, Niconium and Pontic Olbia, from where the cities exported it to mainland Greece at a profit for themselves.[18]

.jpg.webp)

The Scythians were less successful at conquering the Greek cities in the region of the Cimmerian Bosporus, where, although they were initially able to take over Nymphaeum, the other cities built or strengthened city walls, banded together into an alliance under the leadership of Panticapaeum, and successfully defended themselves, after which they united into the Bosporan Kingdom.[18]

At the same time, the Scythians sent a diplomatic mission to Sparta in Greece proper with the goal of establishing a military alliance against the Achaemenid Empire. Ancient Greek authors claim that the Spartans started drinking undiluted wine, which they called the "Scythian fashion" of drinking wine because of these contacts.[164]

After Scyles, coins minted in Pontic Olbia were minted in the name of Eminakos, who was either a governor of the city for Scyles's brother and successor, Octamasadas, or a successor of Octamasadas. Around the same time, there were inner conflicts within the Scythian kingdom, and a new wave of Sauromatian immigrants arrived into Scythia around c. 400 BC, which destabilised it and ended Scythian military activity against the Greek cities of the Pontic shore. Scythian control of the Greek cities ended sometime between 425 and 400 BC, and the cities started reconstituting their khōrai, and Pontic Olbia regained control over the territory it occupied during the Archaic period and expanded it, while Tyras and Niconium also restored their hinterlands. The Scythians lost control of Nymphaeum, which became part of the Bosporan Kingdom that had itself been expanding its territories within the Asian side of the Cimmerian Bosporus. With the arrival of a new wave of Sauromatian immigrants, the Royal Scythians and their allied tribes moved to the western parts of Scythia and expanded into the areas to the south of the Danube corresponding to modern Bessarabia and Bulgaria, and they established themselves in the Dobruja region. One of the Scythian kings who ruled during the later 5th century BC was buried in a sumptuously furnished kurgan located at Agighiol during the early 4th century BC.[18][165]

Golden Age

The Scythian kingdom of the Pontic steppe reached its peak in the 4th century BC, at the same time when the Greek cities of the coast were prospering, and the relations between the two were mostly peaceful; some Scythians had already started becoming sedentary farmers and building fortified and unfortified settlements around the lower reaches of the Dnipro river since the late 5th century BC, and this process intensified throughout the 4th century BC, with the nomadic Scythians settling in multiple villages in the left bank of the Dnister estuary and in small settlements on the lower banks of the Dnipro and of the small steppe rivers which were favourable for agriculture; at the same time, the Scythians sold furs, fish, and grain to the Greeks in exchange of wine, olive oil, and luxury goods,[166] while there was high demand for the Scythians' exports done through the Greek colonies, such as trade goods, grain, slaves, and fish,[166][167] due to which the relations between the Pontic and Aegean regions, and most especially with Athens, were thriving; the importation of Greek products by the forest steppe peoples had instead decreased since the 5th century BC, and the Scythians captured territories from them in the area around what is presently Boryspil during this time.[47] Although the Greek cities of the coast extended their territories considerably, this did not infringe on the Scythians, who still possessed abundant pastures and whose settlements were still thriving, with archaeological evidence suggesting that the population of Crimea, most of whom were Scythians, during this time increased by 600%.[63][18]

The rule of the Spartocid dynasty in the Bosporan Kingdom was also favourable for the Scythians under the rules of Leukon I, Spartocus II and Paerisades I, with Leucon employing Scythians in his army, and the Bosporan nobility had contacts with the Scythians, which might have included matrimonial relations between Scythian and Bosporan royalty.[63][18] By the 4th century BC, the Bosporan kingdom became the main supplier of grains to Greece partly because of the Peloponnesian War that ragied in the latter region, which intensified the grains trade between the Scythians and the Greeks, with the Scythians becoming the principal middlemen in the supply of grains to the Bosporan kingdom: while most of the grains that the Scythians sold to the Greeks was produced by the agricultural populations in the northern forest steppe, the Scythians themselves were also trying to produce more grains within Scythia itself, which was a driving force behind the sedentarisation of many of the hitherto nomadic Scythians; the process of Scythian sedentarisation thus was most intense in the regions adjacent to the Bosporan cities in eastern Crimea.[47]

.jpg.webp)

The Scythian royalty and aristocracy obtained enormous profits from this grains trade, and this period saw Scythian culture not only thriving, with most known Scythian monuments dating from then, but also rapidly undergoing significant Hellenisation. The city of the Kamianka site remained the political, industrial and commercial capital of Scythian during the 4th and early 3rd centuries BC, during which time the Scythians founded a new settlement at Yelizavetovskaya which functioned as the main administrative, commercial and industrial centre of the lower Don river and northern Lake Maeotis areas and was also the residence of local Scythian lords. The main burial centre of the Scythians during this period was located in the Nikopol and Zaporizhzhia region on the lower Dnipro, where were located the Solokha, Chortomlyk, Krasnokutsk and Oleksandropil kurgans. Rich burials, such as, for example, the Chortomlyk mohyla, attest of the wealth acquired from the grains trade by the Scythian aristocracy of the 4th century BC, who were progressively buried with more, relatives, retainers, and grave goods such as gold and silver objects, including Greek-manufactured toreutics and jewellery; the Scythian commoners however did not obtain any revenue from this trade, and luxury items are absent from their burials. Despite the pressure of some smaller and isolated Sarmatian groups in the east, the period remained largely and unusually peaceful and the Scythian hegemony in the Pontic steppe remained undisturbed, with the Scythian nomads continuing to form the bulk of the northern Pontic region's population.[47][63][18]

The most famous Scythian king of the 4th century BC was Ateas, who was the successor and possibly the son of the Scythian king buried at Agighiol, and whose rule started around the 360s BC. By this period, Scythian tribes had already settled permanently on the lands to the south of the Danube, where the people of Ateas lived with their families and their livestock, and possibly in Ludogorie as well, and at this time both Crimea and the Dobruja region started being called "Little Scythia" (Ancient Greek: Μικρα Σκυθια; Latin: Scythia Minor). Although Ateas had united the Scythian tribes under his rule into a rudimentary state and he still ruled over the traditional territories of the Scythian kingdom of the Pontic steppe until at least Crimea, around 350 BC he had also permanently seized some of the lands on the right bank of the Danube from the Thracian Getae, and it appears that he was largely based in the region to the south of the Danube. Under Ateas, the Greek cities to the south of the Danube had also come under Scythian hegemony, including Kallatis, over which he held control and where he probably issued his coins; further attesting of the power that the Scythians held to the south of the Danube in his time, Ateas's main activities which were centred in Thrace and south-west Scythia, such as his wars against the Thracian Triballi and the Dacian Histriani and his threat of conquest against Byzantium, which might be another possible location for where Ateas minted his coins. Ateas initially allied with Philip II of Macedonia, but eventually this alliance fell apart and war broke out between Scythia and Macedonia over the course of 340 to 339 BC, ending with the death of Ateas, at about 90 years old, and the capture of the Scythians' camp and the 20,000 women and children and more than 2,000 pedigree horses living there.[165][47][63][18]

The Scythians appear to have lost some territories on both sides of the Danube due to Ateas's defeat and death, with the Getae moving to the north across the Danube and settling in the lands between the Dnipro and the Prut rivers, although. These changes did not affect Scythian power: the Scythians still continued to nomadise and bury their dead in rich kurgans in the areas to the north-west of the Black Sea between the Dnipro and the Prut; the Scythian capital of the Kamianka site continued to exist as prosperously and extensively as it had before the defeat of Ateas; and the Scythian aristocracy continued burying their dead in barrow tombs which were as sumptuous as those of Ateas's time. In 331 or 330 BC, the Scythians were able to defeat an invasion force of 30,000 men led against them and the Getae by Alexander III's lieutenant Zopyrion and which had managed to attain and besiege Pontic Olbia, with Zopyrion himself getting killed. [63][47][18]

Decline and end

During the end of the 4th century BC, the Scythians were militarily defeated by a king of Macedonia again, this time by Lysimachus in and 313 BC. After this, the Scythians experienced another military defeat when their king Agaros participated in the Bosporan Civil War in 309 BC on the side of Satyros II, son of Paerisades I. After Satyros II was defeated and killed, his son Paerisades fled to Agaros's realm.[45][63][18]

The aftermath of the Scythian conflict with Macedon also coincided with climatic changes and economic crises caused by overgrazed pastures, producing an unfavorable period for the Scythians, and, following their setbacks against the Macedonians, the Scythians came under pressure from the Celts, the Thracian Getae, and the Germanic Bastarnae from the west; at this same time, beginning in the late 4th century BC, another related nomadic Iranic people, the Sarmatians, moved from the east into the Pontic steppe, where their smaller yet more active groups overwhelmed the more numerous yet sedentary Scythians and took over the Scythians' pastures. This deprived the Scythians of their most important resource, causing the collapse of Scythian power and as a consequence Scythian culture suddenly disappeared from the north of the Pontic sea in the early 3rd century BC.[45][63][18]

During the 3rd century BC, the Celts and Bastarnae displaced the Balkan Scythians. The Protogenes inscription, written sometime between 220 and 200 BC, records that the Scythians and the Sarmatian Thisamatae and Saudaratae tribes sought shelter from the allied forces of the Celts and the Germanic Sciri. Due to the Sarmatian, Getic, Celtic, and Germanic encroachments, the Scythian kingdom came to an end and the Scythian kurgans disappeared from the Pontic region,[45][18] replaced as the dominant power of the Pontic steppe by the Sarmatians, while "Sarmatia Europea" (European Sarmatia) replaced "Scythia" as the name for the region.[63]

Little Scythia

_(29608182661).jpg.webp)

Around 200 BC, after their final defeat by the Sarmatian Roxolani, the remnants of the Scythians left their centre at Kamianka and fled to the Scythia Minors in Crimea and in Dobrugea, as well as in nearby regions, their population living in limited, fortified enclaves. The settlements of those Scythians remaining on the Pontic were located in the lower reaches of the Dnieper river. These Scythians were no longer nomadic, having become sedentary, Hellenised farmers, and by the second century BC, these were the only places the Scythians could still be found.[45]

By 50 to 150 AD, most of the Scythians had been assimilated by the Sarmatians.[18] The remaining Scythians of Crimea, who had mixed with the Tauri and the Sarmatians, were conquered in the 3rd century AD by the Goths and other Germanic tribes who were then migrating from the north into the Pontic steppe, and who destroyed Scythian Neapolis.[168]

In subsequent centuries, remaining Scythians and Sarmatians were largely assimilated by early Slavs.[12] The Scythians and Sarmatians played an instrumental role in the ethnogenesis of the Ossetians, who are considered direct descendants of the Alans.[13]

Legacy

The Graeco-Roman peoples were profoundly fascinated by the Scythians. This fascination endured in Europe even after both the disappearance of the Scythians and the end of Graeco-Roman culture, and continued throughout Classical and Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, lasting till the 18th century in the Modern Period.[169]

Antiquity

The ancient Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus wrote legendary accounts of the arrival of the Scythians into the lands of the Cimmerians, accounts for which evidence is lacking:[170][171]

- in one story, Herodotus claimed that the approach of the Scythians led to a civil war among the Cimmerians because the "royal tribe" of the Cimmerians wanted to remain in their lands and defend themselves from the invaders while the rest of the population wanted to leave. This conflict allegedly resulted in the death of the royal tribe, whose bodies were buried near the Dnister river.[172]

- in another account, Herodotus claimed that that the Scythians chased the Cimmerians out of their lands and forced them to migrate to the south into West Asia.[170][171]

By the 5th century BC, the image of the Scythians in Athens had become the quintessential stereotype used for Barbarians, that is for non-Greeks.[173] Following the Greeks' caricatural representation of foreigners as being unmoderated drinkers, they moreso associated the Scythians with drunkenness.[174]

Later Graeco-Roman tradition transformed the Scythian prince Anacharsis into a legendary figure as a kind of "noble savage" who represented "Barbarian wisdom," due to which the ancient Greeks included him as one of the Seven Sages of Greece.[175] Consequently, Anarcharsis became a popular figure in Greek literature,[18] and many legends arose about him, including claims that he had been a friend of Solon.[175] Eventually, Anacharsis completely became an ideal "man of nature" or "noble savage" figure in Greek literature, as well as favourite figure of the Cynics, who ascribed to him a 3rd-century BC work titled the Letters of Anacharsis.[18]

The 4th century BC Greek historian, Ephorus of Cyme, used the perception of Anacharsis as a personification of "Barbarian wisdom" to create an idealised image of the Scythians being as an "invincible" people, which became a tradition of Greek literature.[18] Ephorus created a fictitious account of a legendary Scythian king, named Idanthyrsos or Iandysos, who, 1500 years before the reign of the mythical first Assyrian king Ninus and 3000 years before the first Olympiad, allegedly defeated the equally legendary pharaoh Sesostris and became the ruler of all Asia. This story was a continuation of Ephorus of Cyme's idealisation of the Scythians as an "invincible" people, and was drawn from Herodotus of Halicarnassus's accounts of the Scythian invasion of Asia and the campaign of Darius in Scythia.[176]

In the 4th century BC, the Athenian politician Aeschines referred to the Scythian ancestry of his opponent Demosthenes to attempt discrediting him.[174]

The Ancient Greeks included the Scythians in their mythology, with Herodorus of Heraclea making a mythical Scythian named Teutarus into a herdsman who served Amphitryon and taught archery to Heracles. Herodorus also portrayed the Titan Prometheus as a Scythian king, and, by extension, described Prometheus's son Deucalion as a Scythian as well.[177]

The ancient Israelites called the Scythians ʾAškūz (אשכוז), and this name, corrupted to ʾAškənāz (אשכנז), appears in the Hebrew Bible, where ʾAškənāz is closely linked to Gōmer (גֹּמֶר), that is to the Cimmerians.[50]

The richness of Scythian burials was already well known in Antiquity, and, by the time the power of the Scythians came to an end in the 3rd century BC, the robbing of Scythian graves started[178] and was initially carried out by Scythians themselves.[179]

The Romans confused the peoples whom they perceived as archetypical "Barbarians," namely the Scythians and the Celts, into a single grouping whom they called the "Celto-Scythians" (Latin: Celtoscythae) and supposedly living from Gaul in the west to the Pontic steppe in the east.[180]