| Second Chinese Character Simplification Scheme (Draft) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 第二次汉字简化方案(草案) | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 第二次漢字簡化方案(草案) | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Second round of simplified Chinese characters (abbr. in Chinese) | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 二简字 (二𫈉字) | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 二簡字 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The second round of Chinese character simplification, according to the official document, Second Chinese Character Simplification Scheme (Draft) ("Second Scheme" or "Second Round" for short) to introduce a second round of simplified Chinese characters, was an aborted orthography reform promulgated on 20 December 1977 by the People's Republic of China (PRC). It was intended to replace the existing (first-round) simplified Chinese characters that were already in use. The complete proposal contained two lists. The first list consisting of 248 characters that were to be simplified, and the second list consisting of 605 characters for evaluation and discussion. Of these, 21 from the first list and 40 from the second served as components of other characters, amplifying the impact on written Chinese.

Following widespread confusion and opposition, the second round of simplification was officially rescinded on 24 June 1986 by the State Council. Since then, the PRC has used the first-round simplified characters as its official script. Rather than ruling out further simplification, however, the retraction declared that further reform of the Chinese characters should be done with caution. Today, some second-round simplified characters, while considered nonstandard, continue to survive in informal usage. The issue of whether and how simplification should proceed remains a matter of debate.

_published_in_May_1977.pdf.jpg.webp)

History

The traditional relationship between written Chinese and vernacular Chinese has been compared to that of Latin with the Romance languages in the Renaissance era.[1] The modern simplification movement grew out of efforts to make the written language more accessible, which culminated in the replacement of Classical Chinese (wenyan) with Vernacular Chinese (baihua) in the early 20th century.[2] The fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911 and subsequent loss of prestige associated with classical writing helped facilitate this shift, but a series of further reforms aided by the efforts of reformers such as Qian Xuantong were ultimately thwarted by conservative elements in the new government and the intellectual class.[3][4]

Continuing the work of previous reformers, in 1956 the People's Republic of China promulgated the Scheme of Simplified Chinese Characters, later referred to as the "First Round" or "First Scheme." The plan was adjusted slightly in the following years, eventually stabilizing in 1964 with a definitive list of character simplifications. These are the simplified Chinese characters that are used today in Mainland China and Singapore.[5] Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau did not adopt the simplifications, and the characters used in those places are known as traditional Chinese characters.[6]

Also released in 1964 was a directive for further simplification in order to improve literacy, with the goal of eventually reducing the number of strokes in commonly used characters to ten or fewer. This was to take place gradually, with consideration for both "ease of production [writing] and ease of recognition [reading]." In 1975, a second round of simplifications, the Second Scheme, was submitted by the Script Reform Committee of China to the State Council for approval. Like the First Scheme, it contained two lists, where the first table (comprising 248 characters) was for immediate use, and the second table (comprising 605 characters) for evaluation and discussion.[8] Of these, 21 from the first list and 40 from the second also served as components of other characters, which caused the Second Scheme to modify some 4,500 characters.[9] On 20 December 1977, major newspapers such as the People's Daily and the Guangming Daily published the second-round simplifications along with editorials and articles strongly endorsing the changes. Both newspapers began to use the characters from the first list on the following day.[10]

The Second Scheme was received extremely poorly, and as early as mid-1978, the Ministry of Education and the Central Propaganda Department were asking publishers of textbooks, newspapers and other works to stop using the second-round simplifications. Second-round simplifications were taught inconsistently in the education system, and people used characters at various stages of official or unofficial simplification. Confusion and disagreement ensued.[11]

The Second Scheme was officially retracted by the State Council on 24 June 1986. The State Council's retraction also emphasized that Chinese character reform should henceforth proceed with caution, and that the forms of Chinese characters should be kept stable.[12] Later that year, a final version of the 1964 list was published with minor changes, and no further changes have been made since.[5]

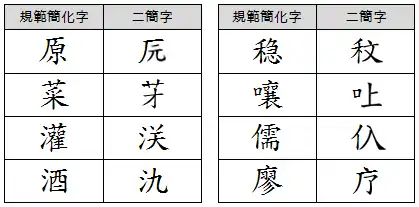

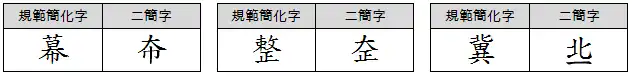

Methods of simplification

The second round of simplification continued to use the methods used in the first round. For example:

In some characters, the phonetic component of the character was replaced with a simpler one, while the radical was unchanged. For example:

In some characters, entire components were replaced by ones that are similar in shape:

- 幕 → 𫯜 (⿱大巾)

- 整 → 𰋞 (⿱大正)

- 迎 → 迊

- 答 → 荅

- 撤 → 𢪃 (⿰扌切)

- 阎 → 闫

In some characters, components that are complicated are replaced with a simpler one not similar in shape but sometimes similar in sound:

- 鞋 → 𰆻 (⿰又圭)

- 短 → 𰦓 (⿰矢卜)

- 道 → 辺

- 嚷 → 𠮵 (⿰口上)

In some characters, the radical is simply dropped, leaving only the phonetic. This results in mergers between previously distinct characters:

- 稀 → 希

- 彩 → 采

- 帮 → 邦

- 蝌蚪 → 科斗

- 蚯蚓 → 丘引

- 豫 → 予

In some characters, entire components are dropped:

- 糖 → 𰪩 (⿰米广)

- 停 → 仃

- 餐 → 歺

- 雪 → 𫜹

- 宣 → 㝉

- 囊 → 𰀉 (⿻一中)

Some characters are simply replaced by a similar-sounding one (a rebus or phonetic loan). This also results in mergers between previously distinct characters:

- 萧 → 肖

- 蛋 → 旦

- 泰 → 太

- 雄 → 厷

- 鳜 → 桂

- 籍 → 笈

- 芭/粑/笆 → 巴

- 蝴/糊/猢 → 胡

- 衩/扠/杈/汊 → 叉

Reasons for failure

The Second Scheme broke with a millennia-long cycle of variant forms coming into unofficial use and eventually being accepted (90 percent of the changes made in the First Scheme existed in mass use, many for centuries[13]) in that it introduced new, unfamiliar character forms.[14][15] The sheer number of characters it changed — the distinction between simplifications intended for immediate use and those for review was not maintained in practice — and its release in the shadow of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1978) have been cited among the chief reasons for its failure.[9][16][17][18] As a result of the Cultural Revolution, trained experts were expelled and the Second Scheme was compiled by the committee and its staffers without outside consultation, which may also have been a factor.[13]

The exact circumstances surrounding the creation and release of the Second Scheme remain shrouded in mystery due to the still-classified nature of many documents and the politically sensitive nature of the issue. However, the Second Scheme is known to have encompassed only about 100 characters before its expansion to over 850.[19] A two-year delay from 1975 to 1977 was officially blamed on Zhang Chunqiao, a member of the Gang of Four; however, there is little historical evidence to support this.[20] Against the political backdrop of the Cultural Revolution, a special section known as the "748 Project" was formed with an emphasis on non-experts, under whose supervision the lists grew significantly. The bulk of the work is believed to have been performed by staffers without proper oversight.[18][21]

The Second Scheme's subsequent rejection by the public has been cited as a case study in a failed attempt to artificially control the direction of a language's evolution.[22] Indeed, it was not embraced by the linguistic community in China upon its release;[23] despite heavy promotion by official publications, Rohsenow observes that "in the case of some of the character forms constructed by the staff members themselves" the public at large found proposed changes "laughable."[24]

Political issues aside, Chen objects to the notion that all characters should be reduced to ten or fewer strokes. He argues that a technical shortcoming of the Second Scheme was that the characters it reformed occur less often in writing than those of the First Scheme. As such it provided less benefit to writers while putting an unnecessary burden on readers in making the characters more difficult to distinguish.[25] Citing several studies, Hannas similarly argues against the lack of differentiation and utility: "it was meaningless to lower the stroke count for its own sake." Thus, he believes simplification and character limitation (reduction of the number of characters)[26] both amount to a "zero-sum game" — simplification in one area of use causing complication in another — and concludes that "the 'complex' characters in Japanese and Chinese, with their greater redundancy and internal consistency, may have been the better bargain."[27]

Effects

While the stated goal of further language reform was not changed, the 1986 conference which retracted the Second Scheme emphasized that future reforms should proceed with caution.[28] It also "explicitly precluded any possibility of developing Hanyu Pinyin as an independent writing system (wénzì)."[29] The focus of language planning policy in China following the conference shifted from simplification and reform to standardization and regulation of existing characters,[30] and the topic of further simplification has since been described as "untouchable" in the field.[31] However, the possibility of future changes remains,[32] and the difficulties the Chinese writing system presents for information technology have renewed the Romanization debate.[33][34]

Today, second round characters are officially regarded as incorrect. However, some have survived in informal contexts; this is because some people who were in school between 1977 and 1986 received their education in second-round characters. For example, eggs at markets are often advertised as "鸡旦" rather than "鸡蛋," parking venues may be marked "仃车" rather than "停车," and street side restaurants as "歺厅" rather than "餐厅." Another example is handwritten license plates from Hebei and Henan provinces, which often use 丠 and 予 as opposed to 冀 and 豫 to represent those provinces.

In three cases, the second round split one family name into two. The first round of simplification had already changed the common surnames 蕭 (Xiāo; 30th most common in 1982) and 閻 (Yán; 50th) into 萧 and 阎. The second round adjusted these further and combined them with other characters previously much less common as surnames: 肖 and 闫. Similarly, 傅 (Fù; 36th) was changed to 付. Following the retraction of the second round, many people still kept the new forms as their surnames so that the three family names are now written six or seven different ways.

Technical information

Most systems of Chinese character encoding, including Unicode and GB 18030, provide full support for the first list of second-round characters,[35] and only partial support for the second list, with many such characters unencoded or yet to be standardized. Mojikyo supports the characters on the first list. Also, the font "SongUni-PUA" is composed primarily of the second-round characters.

Example text

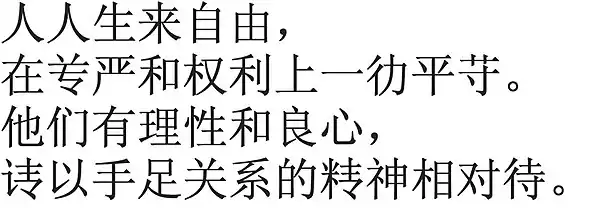

From Article 1 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Second Round Simplified Chinese:

- First-round Simplified Chinese script: 人人生来自由,在尊严和权利上一律平等。他们有理性和良心,请以手足关系的精神相对待。

- Traditional Chinese script: 人人生來自由,在尊嚴和權利上一律平等。他們有理性和良心,請以手足關係的精神相對待。

Notes

- ↑ Hannas (1997), p. 248.

- ↑ Chen (1999), p. 70-75.

- ↑ Chen (1999), p. 150-153.

- ↑ Rohsenow (2004), p. 22.

- 1 2 See Chen 1999, pp. 154–155 for information on Singapore. Note that, while Singapore adopted the First Scheme, it did not follow suit with the Second Scheme.

- ↑ Chen (1999), p. 162-163.

- ↑ Ramsey 1989, pp. 146–147. "The publication of the 1964 list was meant to clarify what the limits [of character simplification] were. These limits again became obscure, however, with the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Character simplification had been represented all along as a kind of Marxist, proletarian process; as a consequence, coining and using new characters became a popular way to show that one's writing was being done in right spirit. Wall slogans, signs, and mimeographed literature of all kinds began to be embellished with abbreviations never seen before. Within a short time the Committee on Language Reform had turned to the task of collecting characters 'simplified by the masses'..." (emphasis added)

- ↑ Chen (1999), p. 155-160.

- 1 2 Hannas (1997), p. 22-24.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 62.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 62-64.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 51.

- 1 2 Chen (1999), p. 155-156.

- ↑ Hannas (1997), p. 223-224.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 67-68.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 66-69.

- ↑ Chen (1999), p. 160.

- 1 2 Rohsenow (2004), p. 29.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 54.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 58.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 54-62.

- ↑ Hodge & Louie (1998), p. 63-64.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 63.

- ↑ Rohsenow (2004), p. 28-29.

- ↑ Chen (1999), p. 160-162.

- ↑ Hannas (1997), p. 215.

- ↑ Hannas (1997), p. 226-229.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 64.

- ↑ Rohsenow (2004), p. 30.

- ↑ Rohsenow (2004), p. 32.

- ↑ Zhao & Baldauf (2007), p. 299-300.

- ↑ See Zhao & Baldauf 2007, pp. 299–312 (chapter 7, section 3) "Crackling the Hard Nut: Dealing with the Rescinded Second Scheme and Banned Traditional Characters".

- ↑ Hannas (1997), p. 25.

- ↑ See Zhao & Baldauf 2007, pp. 288–299 (chapter 7, section 2) "Romanization - Old Questions, New Challenge". Also see Chen 1999, p. 164 (chapter 10) "Phonetization of Chinese".

- ↑ Alexander, Zapryagaev (2019-09-30). "IRGN2414" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-02-03.

References

- Chen, Ping (1999). Modern Chinese: History and Sociolinguistics (4th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64572-0.

- DeFrancis, John (1984). The Chinese Language: Fact and Fantasy. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1068-9.

- Hannas, William C. (1997). Asia's Orthographic Dilemma. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1892-0.

- Hodge, Bob; Louie, Kam (1998). The Politics of Chinese Language and Culture: The Art of Reading Dragons. Culture and communication in Asia. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-17266-0.

- Ramsey, S. Robert (1989). The Languages of China. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- Rohsenow, John S. (2004). "Fifty Years of Script and Language Reform in the PRC". In Minglang Zhou; Hongkai Sun (eds.). Language Policy in the People's Republic of China: Theory and Practice Since 1949. Language policy. Vol. 4. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4020-8038-8.

- Zhao, Shouhui; Baldauf, Richard B. Jr. (2007). Planning Chinese Characters: Reaction, Evolution or Revolution?. Language policy. Vol. 9. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-48574-4.

External links

- Andrew West, Proposal to Encode Obsolete Simplified Chinese Characters (PDF version), section 4: Second Stage Simplified Characters (1977)

- BabelStone Fonts : BabelStone Erjian