| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Other names

Selenium(IV) oxide Selenous anhydride | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.358 |

| EC Number |

|

PubChem CID |

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

| UN number | 3283 |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| SeO2 | |

| Molar mass | 110.96 g/mol |

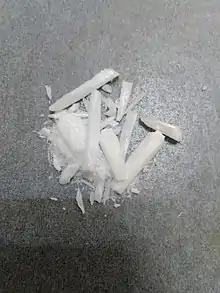

| Appearance | White crystals, turn slightly pink with trace decomposition[1] |

| Odor | rotten radishes |

| Density | 3.954 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | 340 °C (644 °F; 613 K) (sealed tube) |

| Boiling point | 350 °C (662 °F; 623 K) subl. |

| 38.4 g/100 mL (20 °C) 39.5 g/100 ml (25 °C) 82.5 g/100 mL (65 °C) | |

| Solubility | soluble in benzene |

| Solubility in ethanol | 6.7 g/100 mL (15 °C) |

| Solubility in acetone | 4.4 g/100 mL (15 °C) |

| Solubility in acetic acid | 1.11 g/100 mL (14 °C) |

| Solubility in methanol | 10.16 g/100 mL (12 °C) |

| Vapor pressure | 1.65 kPa (70 °C) |

| Acidity (pKa) | 2.62; 8.32 |

| −27.2·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD) |

> 1.76 |

| Structure | |

| see text | |

| trigonal (Se) | |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards |

Toxic by ingestion and inhalation[2] |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H301, H331, H373, H410 | |

| P260, P261, P264, P270, P271, P273, P301+P310, P304+P340, P311, P314, P321, P330, P391, P403+P233, P405, P501 | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LCLo (lowest published) |

5890 mg/m3 (rabbit, 20 min) 6590 mg/m3 (goat, 10 min) 6590 mg/m3 (sheep, 10 min)[3] |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | ICSC 0946 |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions |

Selenium disulfide |

Other cations |

Sulfur dioxide Tellurium dioxide |

| Selenium trioxide | |

Related compounds |

Selenous acid |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Selenium dioxide is the chemical compound with the formula SeO2. This colorless solid is one of the most frequently encountered compounds of selenium.

Properties

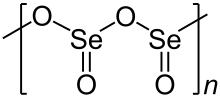

Solid SeO2 is a one-dimensional polymer, the chain consisting of alternating selenium and oxygen atoms. Each Se atom is pyramidal and bears a terminal oxide group. The bridging Se-O bond lengths are 179 pm and the terminal Se-O distance is 162 pm.[4] The relative stereochemistry at Se alternates along the polymer chain (syndiotactic). In the gas phase selenium dioxide is present as dimers and other oligomeric species, at higher temperatures it is monomeric.[5] The monomeric form adopts a bent structure very similar to that of sulfur dioxide with a bond length of 161 pm.[5] The dimeric form has been isolated in a low temperature argon matrix and vibrational spectra indicate that it has a centrosymmetric chair form.[4] Dissolution of SeO2 in selenium oxydichloride give the trimer [Se(O)O]3.[5] Monomeric SeO2 is a polar molecule, with the dipole moment of 2.62 D [6] pointed from the midpoint of the two oxygen atoms to the selenium atom.

The solid sublimes readily. At very low concentrations the vapour has a revolting odour, resembling decayed horseradishes. At higher concentrations the vapour has an odour resembling horseradish sauce and can burn the nose and throat on inhalation. Whereas SO2 tends to be molecular and SeO2 is a one-dimensional chain, TeO2 is a cross-linked polymer.[4]

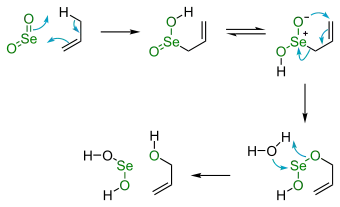

SeO2 is considered an acidic oxide: it dissolves in water to form selenous acid.[5] Often the terms selenous acid and selenium dioxide are used interchangeably. It reacts with base to form selenite salts containing the SeO2−

3 anion. For example, reaction with sodium hydroxide produces sodium selenite:

- SeO2 + 2 NaOH → Na2SeO3 + H2O

Preparation

Selenium dioxide is prepared by oxidation of selenium by burning in air or by reaction with nitric acid or hydrogen peroxide, but perhaps the most convenient preparation is by the dehydration of selenous acid.

- 2 H2O2 + Se → SeO2 + 2 H2O

- 3 Se + 4 HNO3 + H2O → 3 H2SeO3 + 4 NO

- H2SeO3 ⇌ SeO2 + H2O

Occurrence

The natural form of selenium dioxide, downeyite, is a very rare mineral. It is only found at a small number of burning coal banks, where it forms around vents created from escaping gasses.[7]

Uses

Organic synthesis

SeO2 is an important reagent in organic synthesis. Oxidation of paraldehyde (acetaldehyde trimer) with SeO2 gives glyoxal[8] and the oxidation of cyclohexanone gives 1,2-cyclohexanedione.[9] The selenium starting material is reduced to selenium, and precipitates as a red amorphous solid which can easily be filtered off.[9] This type of reaction is called a Riley oxidation. It is also renowned as a reagent for "allylic" oxidation,[10] a reaction that entails the following conversion

This can be described more generally as;

- R2C=CR'-CHR"2 + [O] → R2C=CR'-C(OH)R"2

where R, R', R" may be alkyl or aryl substituents.

Selenium dioxide can also be used to synthesize 1,2,3-selenadiazoles from acylated hydrazone derivatives.[11]

As a colorant

Selenium dioxide imparts a red colour to glass. It is used in small quantities to counteract the colour due to iron impurities and so to create (apparently) colourless glass. In larger quantities, it gives a deep ruby red colour.

Selenium dioxide is the active ingredient in some cold-bluing solutions.

It was also used as a toner in photographic developing.

Safety

Selenium is an essential element, but ingestion of more than 5 mg/day leads to nonspecific symptoms.[12]

References

- ↑ "Safety data sheet: Selenium dioxide" (PDF). integrachem.com. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ↑ "Selenium dioxide safety and hazards". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ↑ "Selenium compounds (as Se)". Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health Concentrations (IDLH). National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH).

- 1 2 3 Handbook of Chalcogen Chemistry: New Perspectives in Sulfur, Selenium and Tellurium, Franceso A. Devillanova, Royal Society of Chemistry, 2007, ISBN 9780854043668

- 1 2 3 4 Holleman, Arnold Frederik; Wiberg, Egon (2001), Wiberg, Nils (ed.), Inorganic Chemistry, translated by Eagleson, Mary; Brewer, William, San Diego/Berlin: Academic Press/De Gruyter, ISBN 0-12-352651-5

- ↑ Takeo, Harutoshi; Hirota, Eizi; Morino, Yonezo (1972). "Third-order potential constants and dipole moment of SeO2 by microwave spectroscopy". Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy. 41 (2): 420–422. Bibcode:1972JMoSp..41..420T. doi:10.1016/0022-2852(72)90216-0. ISSN 0022-2852.

- ↑ Finkelman, Robert B.; Mrose, Mary E. (1977). "Downeyite, the first verified natural occurrence of SeO2" (PDF). American Mineralogist. 62: 316–320.

- ↑ Ronzio, A. R.; Waugh, T. D. (1955). "Glyoxal Bisulfite". Organic Syntheses.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, vol. 3, p. 438 - 1 2 Hach, C. C. Banks, C. V.; Diehl, H. (1963). "1,2-Cyclohexanedione Dioxime". Organic Syntheses.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, vol. 4, p. 229 - ↑ Coxon, J. M.; Dansted, E.; Hartshorn, M. P. (1988). "Allylic Oxidation with Hydrogen Peroxide–Selenium Dioxide: trans-Pinocarveol". Organic Syntheses.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, vol. 6, p. 946 - ↑ Lalezari, Iraj; Shafiee, Abbas; Yalpani, Mohamed (1969). "A novel synthesis of selenium heterocycles: substituted 1,2,3-selenadiazoles". Tetrahedron Letters. 10 (58): 5105–5106. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)88895-X.

- ↑ Bernd E. Langner "Selenium and Selenium Compounds" in Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_525