| Septet in E♭ major | |

|---|---|

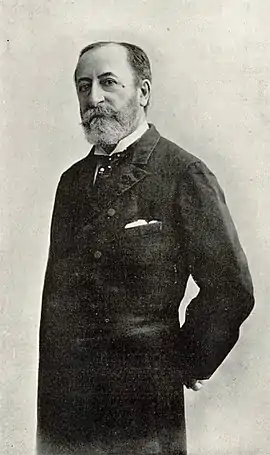

| by Camille Saint-Saëns | |

.jpg.webp) Title page of the autograph, with a drawing of a trumpet in the center. The note on the right bottom, added by Lemoine, tells the work's compositional history.[n 1] | |

| Key | E♭ major |

| Opus | 65 |

| Composed | 1879–80 |

| Dedication | Émile Lemoine |

| Published | March 1881 (Durand) |

| Movements | 4 |

| Scoring |

|

| Premiere | |

| Date | 6 January 1880 (Préambule) 28 December 1880 (complete work) |

| Location | Paris |

The Septet in E♭ major, Op. 65, was written by Camille Saint-Saëns between 1879 and 1880 for the unusual combination of trumpet, two violins, viola, cello, double bass and piano.[1] Like the suites Opp. 16, 49, 90, the septet is a neoclassical work that revives 17th-century French dance forms, reflecting Saint-Saëns's interest in the largely forgotten French musical traditions of the 17th century.[2]

History

The septet is dedicated to Émile Lemoine, a mathematician who in 1861 founded the chamber music society La Trompette. Saint-Saëns and other well known musicians such as Louis Diémer, Martin Pierre Marsick, and Isidor Philipp would often perform at the concerts of the society, which took place at Salle Érard and later in the hall of the Horticultural Society.[1] For many years, Lemoine had asked Saint-Saëns to compose a special piece with the trumpet to justify the name of the society, and jokingly he would respond that he could create a work for guitar and thirteen trombones. Saint-Saëns eventually relented, and in 1879 presented to Lemoine a piece titled Préambule as a Christmas present, later promising to complete the work with the Préambule as the first movement.[3]

The complete septet was successfully premiered on 28 December 1880. The string quartet was doubled at the premiere – in Saint-Saëns' opinion, it made a stronger impact that way. The work was first published in March 1881 with Durand.[4]

Structure

| External audio | |

|---|---|

| Performed by Thomas Stevens, Julie Rosenfeld, Ani Kavafian, Toby Hoffman, Carter Brey, Jack Kulowitsch and André Previn | |

The work consists of four movements, each around four minutes in length.[3]

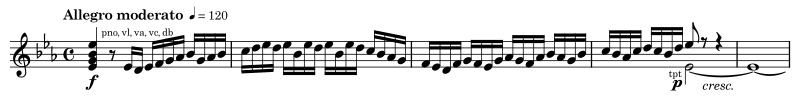

- Préambule (Allegro moderato, E♭ major)

- The pompous opening with a flourish of unison scales leads to the trumpet's entrance on a sustained E♭.[5] The piano part, in the style of a virtuoso concerto, looks somewhat out of place. A march-like fugue establishes order, treating the theme in a manner similar to Schumann's Piano Quintet. Throughout the movement, romantic elements manage to break through baroque motoricism.[6]

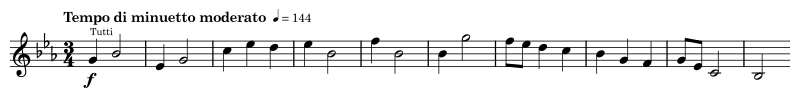

- Menuet (Tempo di minuetto moderato, E♭ major)

- The minuet uses "baroque clichés" even more strikingly than the first movement. Influences of Lully and Handel are mixed with romantic elements. The central trio features an elegant melody;[6] Keller calls it a "gem of light lyricism in which the piano embroiders the strings' melody with a filigree of decoration."[5]

- Intermède (Andante, C minor)

- The Intermède (interlude), initially titled Marche funèbre,[1] is the work's only fully romantic movement: a minor-key cantilena over a Bolero-style rhythm.[6] The main theme is first introduced in the cello, and then played in succession by the viola, the violins, and the trumpet, while the piano provides a rhythmic ostinato; Keller calls the effect "rather Schumannesque".[5]

- Gavotte et Finale (Allegro non troppo, E♭ major)

Legacy

Hugo Wolf, who attended a performance of the septet in Vienna on 1 January 1887, wrote: "What was most engaging about this piece, distinguished by its skillful exploitation of the trumpet, was its brevity. A bit longer, and it would be a bore. This shrewd moderation and pithiness is admirable, and absolutely not to be underestimated. How many a German composer might envy Saint-Saëns this virtue!"[5] Of Saint-Saëns's works, it was the septet that he reportedly liked most.[7]

In October 1907, Saint-Saëns confessed to Lemoine: "When I think how much you pestered me to make me produce, against my better judgment, this piece that I did not want to write and which has become one of my great successes, I never understood why."[n 2]

The septet was performed at Saint-Saëns' last public appearance as a pianist, shortly before his death, on the occasion of a celebration that Académie des Beaux-Arts members threw for him.[5]

James Keller writes that the septet "stands as a curiosity of instrumentation that balances its forces with far greater success than one might anticipate. Portions of this appealing and entertaining work rank high on the scale of musical humor."[5] Jeremy Nicholas has called the septet a neglected masterpiece, alongside the Piano Quartet and the First Violin Sonata.[8]

Arrangements

Numerous arrangements of the septet were made, including one for piano trio by Saint-Saëns himself (November 1881), and the Menuet and Gavotte for two pianos (August 1881). His pupil Gabriel Fauré arranged the work for piano duet (October 1881). Albert Périlhou made a concert transcription of the Gavotte (April 1886).[1]

References

Notes

- ↑ "Here is the history of this piece. For many years I had been pestering my friend Saint-Saëns by asking him to compose, for our trumpet evenings, a serious work in which there is a trumpet mixed with the string instruments and the piano that we usually had; he first joked to me about this strange combination of instruments, saying that he would compose a piece for guitar and thirteen trombones. In 1879 he gave me (on December 29th), probably as a Christmas gift, a piece for trumpet, piano, string quartet and double bass entitled Préambule and I played it on 6 January 1880 at our first concert. Saint-Saëns probably liked the performance because he told me on leaving the Conservatory: 'You will have your complete piece, the Préambule will be the first movement'. He kept his word and the complete septet [...] was performed for the first time on 28 December 1880 (the beginning of our evenings of the season). [...] The artists were: [...] The septet can of course be played with only one instrument for each part of the strings, but (in the opinion of the composer) it is more effective if the quartet is doubled! It is very beautiful with an orchestra, I heard it like that with the Concerts Colonne. Paris, 2 April 1894, E. Lemoine. ("Voici l'historique de ce morceau. Depuis de longues années je tracassais mon ami Saint-Saëns en lui demandant de me composer, pour nos soirées de la trompette, une œuvre sérieuse où il y ait une trompette mêlée aux instruments à cordes et au piano que nous avions ordinairement; il me plaisanta d'abord sur cette combinaison bizarre d'instruments répondant qu'il ferait avant un morceau pour guitare et treize trombones etc. En 1879 ilme remit (le 29 Décembre), sans doute pour mes étrennes, un morceau pour trompette, piano, quatuor et contrebasse intitulé Préambule et je le fis jouer le 6 Janvier 1880 à notre première soirée. L'essai plut sans doute à Saint-Saëns car il me dit en sortant: 'Tu auras ton morceau complet, le Préambule en sera le 1° mouvement.' Il a tenu parole et le septuor complet [...] a été joué pour la première fois le 28 Décembre 1880 (Début de nos soirées de la saison). [...] Les artistes étaient: [...] Ce septuor peut naturellement se jouer avec un seul instrument pour chaque partie des cordes mais il fait (de l'avis de l'auteur), meilleur effet si le quatuor est doublé! Il est très beau avec l'orchestre, je l'ai entendu ainsi aux Concerts Colonne. Paris le 2 avril 1894, E. Lemoine.")[1]

- ↑ "Quand je pense combien tu m'as tourmenté pour me faire faire malgré moi ce morceau que je ne voulais pas faire et qui est devenu un de mes grands succès, je n'ai jamais compris pourquoi."[3]

Sources

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ratner, Sabina Teller (2002). Camille Saint-Saëns, 1835–1922: A Thematic Catalogue of his Complete Works, Volume 1: The Instrumental Works. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 174–178. ISBN 978-0-19-816320-6.

- ↑ Fallon, Daniel M.; Harding, James; Ratner, Sabina Teller (2001). "Saint-Saëns, (Charles) Camille". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- 1 2 3 Ratner, Sabina Teller (2005). Notes to Hyperion CD Saint-Saëns Chamber Music. London: Hyperion Records. OCLC 61134605.

- ↑ Jost, Peter (2015). Camille Saint-Saëns, Septet E flat major op. 65 – Preface. Munich: G. Henle Verlag. pp. IV–V. ISMN 979-0-2018-0584-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Keller, James (2011). Chamber Music: A Listener's Guide. Oxford University Press. pp. 386–387. ISBN 978-0-19-538253-2. OCLC 551723673.

- 1 2 3 4 Böhmer, Karl. "Camille Saint-Saens, Septett, op. 65". Villa Musica (in German). Retrieved 18 January 2021.

- ↑ Newman, Ernest (1907). Hugo Wolf (2013 new ed.). Dover Publications. p. 39.

- ↑ Nicholas, Jeremy. "Camille Saint-Saëns". BBC Music Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

External links

- Septet (Saint-Saëns): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Septet on YouTube, performed by members of the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne Orchesterakademie