| Šērūʾa-ēṭirat | |

|---|---|

| Princess of Assyria | |

| Queen consort of the Scythians (?) | |

| Spouse | Bartatua (?) |

| Issue | Madyes (?) |

| Akkadian | (Šērūʾa-ēṭirat or Šeruʾa-eṭirat) |

| Dynasty | Sargonid dynasty |

| Father | Esarhaddon |

| Mother | Ešarra-ḫammat (?) |

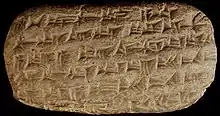

Šērūʾa-ēṭirat (Akkadian: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Šērūʾa-ēṭirat[1] or Šeruʾa-eṭirat,[2] meaning "Šerua is the one who saves"),[3][4] called Saritrah (Demotic:

Šērūʾa-ēṭirat[1] or Šeruʾa-eṭirat,[2] meaning "Šerua is the one who saves"),[3][4] called Saritrah (Demotic: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , sꜣrytꜣr)[5] in later Aramaic texts, was an ancient Assyrian princess of the Sargonid dynasty, the eldest daughter of Esarhaddon and the older sister of his son and successor Ashurbanipal. She is the only one of Esarhaddon's daughters to be known by name and inscriptions listing the royal children suggest that she outranked several of her brothers, such as her younger brother Aššur-mukin-paleʾa, but ranked below the crown princes Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin. Her importance could be explained by her possibly being the oldest of all Esarhaddon's children.

, sꜣrytꜣr)[5] in later Aramaic texts, was an ancient Assyrian princess of the Sargonid dynasty, the eldest daughter of Esarhaddon and the older sister of his son and successor Ashurbanipal. She is the only one of Esarhaddon's daughters to be known by name and inscriptions listing the royal children suggest that she outranked several of her brothers, such as her younger brother Aššur-mukin-paleʾa, but ranked below the crown princes Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin. Her importance could be explained by her possibly being the oldest of all Esarhaddon's children.

Šērūʾa-ēṭirat lived into Ashurbanipal's reign, although her eventual fate is unknown; she may have been married to the Scythian king Bartatua and have become the mother of his successor Madyes; a later Aramaic story has her play a central role in attempting to broker peace between Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin on the eve of their civil war in 652 BCE and disappearing after Ashurbanipal kills his brother.

Biography

Esarhaddon, who reigned as king of Assyria from 681 to 669 BCE, had several daughters, but Šērūʾa-ēṭirat is the only one known by name. Her name frequently appears in contemporary inscriptions.[1] At least one other daughter, though unnamed, is known from lists of the royal children and Šērūʾa-ēṭirat is explicitly designated as the "eldest daughter", meaning there would have been other princesses.[6] Because lists of the royal children are inconsistent in order, it is difficult to determine the age of Šērūʾa-ēṭirat relative to her male siblings.[7] She is usually listed after the crown princes Ashurbanipal (who was set to inherit Assyria) and Shamash-shum-ukin (who was set to inherit Babylon) but ahead of the younger brothers Aššur-mukin-paleʾa and Aššur-etel-šamê-erṣeti-muballissu. As such, she seems to have ranked third among the royal children, despite there being more than two sons.[8] She was older than Ashurbanipal and one theory in regards to her high status is that she might have been the oldest of Esarhaddon's children.[7]

Šērūʾa-ēṭirat's name is listed among the names of her brothers in a document concerning the foods and potential gifts of the New Year's celebration and she is also named in a grant by Ashurbanipal. She also appears in a medical report on the royal family from 669 BCE.[9] She is known to have performed sacrifices to the god Nabu together with the male children and to have been present at events and ceremonial banquets alongside her male siblings.[6] She also appears in a text from the reign of Esarhaddon or Ashurbanipal wherein Nabu-nadin-shumi, the chief exorcist in Babylonia, writes to the princess to say that he is praying for her father and for her.[9]

Marriage to Bartatua

Esarhaddon's questions to the oracle of the Sun-god Shamash mention that Bartatua, a Scythian king who sought a rapprochement with the Assyrians, in 672 BCE asked for the hand of a daughter of Esarhaddon in marriage.[10] Šērūʾa-ēṭirat may have married Bartatua, though the marriage itself is not recorded in the Assyrian texts. The close alliance between the Scythians and Assyria under the reigns of Bartatua and his son and successor Madyes suggests that the Assyrian priests did approve of this marriage between a daughter of an Assyrian king and a nomadic lord, which had never happened before in Assyrian history; the Scythians were thus brought into a marital alliance with Assyria, and Šērūʾa-ēṭirat may have been the mother of Bartatua's son Madyes.[11][12][13][14][15]

Bartatua's marriage to Šērūʾa-ēṭirat required would have required that he pledge allegiance to Assyria as a vassal, and in accordance to Assyrian law, the territories ruled by him would be his fief granted by the Assyrian king, which made the Scythian presence in Western Asia a nominal extension of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.[10] Under this arrangement, the power of the Scythians in Western Asia heavily depended on their cooperation with the Assyrian Empire, due to which the Scythians henceforth remained allies of the Assyrian Empire until it started unravelling after the death of Esarhaddon's successor Ashurbanipal.[16]

Letter to Libbāli-šarrat

Although Šērūʾa-ēṭirat is mentioned in several royal inscriptions, she is most known for her letter to her sister-in-law Libbāli-šarrat, wife of her brother, the crown prince Ashurbanipal, written around c. 670 BCE. In this letter, Šērūʾa-ēṭirat she respectfully reprimands Libbāli-šarrat for not studying and also reminds her that though Libbāli-šarrat is to become the future queen, Šērūʾa-ēṭirat still outranks her as she is the king's daughter (a title that would have been rendered as marat šarri, "daughter of the king", in Akkadian) whilst Libbāli-šarrat is only the king's daughter-in-law.[1][7][8] Translated into English, Šērūʾa-ēṭirat's letter reads:[17]

Word of the king's daughter to Libbāli-šarrat.

Why don't you write your tablet and do your homework? For if you don't, they will say: "Is this the sister of Šērūʾa-ēṭirat, the eldest daughter of the Succession Palace of Aššur-etel-ilani-mukinni,[n 1] the great king, mighty king, king of the world, king of Assyria?"

Yet you are only a daughter-in-law — the lady of the house of Ashurbanipal, the great crown prince designate of Esarhaddon, king of Assyria.[17]

The opening of the letter ("word of the king's daughter") is striking. The opening "this is the word of the king" was usually only used by the king himself. The letter suggests that shame would be brought on the royal house if Libbāli-šarrat was unable to read and write.[2] Some scholars have interpreted the letter as a sign that there was sometimes social tension between the denizens of the ancient Assyrian royal palace.[9]

Later years

The title of Šērūʾa-ēṭirat after Esarhaddon's death was ahat šarri ("sister of the king").,[19] although the role she played in the court of her brother Ashurbanipal once Esarhaddon was dead and her eventual fate are both unknown.[7]

Legacy

A later Aramaic story based on the civil war between her brothers Ashurbanipal and Shamash-shum-ukin (652–648 BCE) gives Saritrah (Šērūʾa-ēṭirat) a central role in the negotiations before the civil war started around 652 BCE.[7][9] In the story, Šērūʾa-ēṭirat attempts to broker peace between Sarbanabal (Ashurbanipal) and Sarmuge (Samash-shum-ukin).[9] When this fails and Sarbanabal kills Sarmuge, Saritrah disappears, possibly into exile.[20]

If Šērūʾa-ēṭirat's married Bartatua she was likely the mother of his successor Madyes, who brought Scythian power in Western Asia to its peak.[10] After the Neo-Assyrian Empire started unravelling following Ashurbanipal's death, Madyes was assassinated by the Median king Cyaxares, who expelled the Scythians from Western Asia.[21][22]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 Teppo 2007, p. 394.

- 1 2 Novotny & Singletary 2009, p. 168.

- ↑ "Šeruʾa-eṭerat [1] (PN)". Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus. University of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ Roth 1958, p. 403.

- ↑ Nims & Steiner 1985.

- 1 2 Kertai 2013, p. 119.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Novotny & Singletary 2009, pp. 172–173.

- 1 2 Melville 2004, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Teppo 2007, p. 395.

- 1 2 3 Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 564-565.

- ↑ Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, pp. 566–567: "Bartatua was probably well aware of the precarious position of Esarhaddon in 674, and must have considered himself powerful enough to ask in marriage the hand of the Assyrian princess, Shernʾa-etert, Esarhaddon's daughter. Esarhaddon apparently did not resent her marriage to a barbarian, but his fear was that ‘the sacrifice’ might be in vain. ... History does not explicitly tell us whether Bartatua actually married the Assyrian royal princess, but this seems to ensue from the firm Assyro-Scythian alliance and the loyal support of Assyria by the Scythians nearly to the end of that kingdom."

- ↑ Barnett 1991.

- ↑ Diakonoff 1985, pp. 89–109: "Protothyes asked for the hand of Esarhaddon's daughter, and the question put to the oracle is about the expediency of a favourable reply. ... The Assyrian priests apparently sanctioned the unprecedented marriage of a daughter of an Assyrian king to a nomad chief, seeing that subsequent events are best interpreted on the assumption that both Protothyes and his son Madyes became and remained loyal allies of Assyria during almost half a century."

- ↑ Bukharin 2011: "С одной стороны, Мадий, вероятно, полуассириец, даже будучи «этническим» полускифом (его предшественник и, вероятно, отец, ‒ царь скифов Прототий, женой которого была дочь ассирийского царя Ассархаддона)" [On the one hand, Madyes is probably a half-Assyrian, even being an “ethnic” half-Scythian (his predecessor and, probably, father, is the king of the Scythians Protothyes, whose wife was the daughter of the Assyrian king Essarhaddon)]

- ↑ Ivantchik 2018: "In approximately 672 BCE the Scythian king Partatua (Protothýēs of Hdt., 1.103) asked for the hand of the daughter of the Assyrian king Esarhaddon, promising to conclude a treaty of alliance with Assyria. It is probable that this marriage took place and the alliance also came into being (SAA IV, no. 20; Ivantchik, 1993, pp. 93-94; 205-9)."

- ↑ Sulimirski & Taylor 1991, p. 564-567.

- 1 2 Barjamovic 2011, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Halton & Svärd 2017, p. 150.

- ↑ Melville 2004, p. 38.

- ↑ Lipiński 2006, p. 183.

- ↑ Diakonoff 1985, p. 119.

- ↑ Diakonoff 1993.

Sources

- Barjamovic, Gojko (2011). "Pride, Pomp and Circumstance". Royal Courts in Dynastic States and Empires: A Global Perspective. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-20622-9.

- Barnett, R. D. (1991). "Urartu". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E. (eds.). The Prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 356–365. ISBN 978-1-139-05428-7.

- Bukharin, Mikhail Dmitrievich [in Russian] (2013). "Колаксай и его братья (античная традиция о происхождении царской власти у скифов" [Kolaxais and his Brothers (Classical Tradition on the Origin of the Royal Power of the Scythians)]. Аристей: вестник классической филологии и античной истории (in Russian). 8: 20–80. Retrieved 2022-07-27.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1985). "Media". In Gershevitch, Ilya (ed.). The Median and Achaemenian Periods. The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 2. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 978-0-521-20091-2.

- Diakonoff, I. M. (1993). "CYAXARES". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York City, United States: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation; Brill Publishers. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Halton, Charles; Svärd, Saana (2017). Women's Writing of Ancient Mesopotamia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107052055.

- Ivantchik, Askold (1993). "SCYTHIANS". Encyclopædia Iranica. New York City, United States: Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation; Brill Publishers. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Kertai, David (2013). "The Queens of the Neo-Assyrian Empire". Altorientalische Forschungen. 40 (1): 108–124. doi:10.1524/aof.2013.0006. S2CID 163392326.

- Lipiński, Edward (2006). On the Skirts of Canaan in the Iron Age: Historical and Topographical Researches. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Vol. 153. Leuven, Belgium: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-9-042-91798-9.

- Melville, Sarah C. (2004). "Neo-Assyrian Royal Women and Male Identity: Status as a Social Tool". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 124 (1): 37–57. doi:10.2307/4132152. JSTOR 4132152.

- Nims, Charles F.; Steiner, Richard C. (1985). "Ashurbanipal and Shamash-Shum-Ukin : A Tale of Two Brothers from the Aramaic Text in Demotic Script: Part 1". Revue Biblique. 91 (1): 60–81. JSTOR 44088732.

- Novotny, Jamie; Singletary, Jennifer (2009). "Family Ties: Assurbanipal's Family Revisited". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 106: 167–177.

- Roth, Martha T. (1958). The Assyrian Dictionary of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, Volume 4 (E). University of Chicago Press.

- Teppo, Saana (2007). "Agency and the Neo-Assyrian Women of the Palace". Studia Orientalia Electronica. 101: 381–420.

- Sulimirski, Tadeusz; Taylor, T. F. (1991). "The Scythians". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. The Cambridge Ancient History. Vol. 3. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 547–590. ISBN 978-1-139-05429-4.