.jpg.webp)

The Seventh India Armada was assembled in 1505 on the order of King Manuel I of Portugal and placed under the command of D. Francisco de Almeida, the first Portuguese Viceroy of the Indies. The 7th Armada set out to secure the dominance of the Portuguese navy over the Indian Ocean by establishing a series of coastal fortresses at critical points – Sofala, Kilwa, Anjediva, Cannanore – and reducing cities perceived to be local threats (Kilwa, Mombasa, Onor).

Background

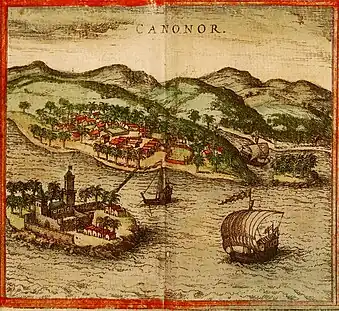

By 1504, the Portuguese crown had already sent six armadas to India. The expeditions had opened hostilities with Calicut (Calecute, Kozhikode), the principal entrepôt of the Kerala pepper trade and dominant city-state on the Malabar coast of India. To counter the power of the ruling Zamorin of Calicut, the Portuguese forged alliances and established factories in three smaller rival coastal states, Cochin (Cochim, Kochi), Cannanore (Canonor, Kannur) and Quilon (Coulão, Kollam).

When the Portuguese India Armadas were in India (August to January), the Portuguese position in India was safe – the Calicut fleet was no match against the superior Portuguese naval and cannon technology of the armada. But in the spring and summer months, when the armada was absent, the Portuguese factories were very vulnerable. The armies of the Zamorin of Calicut had nearly overrun Cochin twice in the intervening years. The Fifth Armada (1503) under Afonso de Albuquerque had erected a small timber fortress, (Fort Sant'Iago, soon to be renamed Fort Manuel), to protect the factory in Cochin. The Sixth Armada (1504), under Lopo Soares de Albergaria had dropped off a larger Portuguese garrison and a small coastal patrol to harass Calicut and protect the allied cities. But this was not nearly enough against a Zamorin that could call on an army of tens of thousands. While the Zamorin's vast army had been humiliated at the Battle of Cochin (1504), it was a close-run thing, and he might have better luck next time.

The Zamorin was quick to realize the urgency of rectifying the imbalance in naval and cannon power. To this end, he called on his old partners in the spice trade. The Venetians had already dispatched a couple of military engineers to help the Zamorin forge European cannon. The Ottomans had dispatched some shipments of firearms. But the critical missing factor was a fleet that could match the Portuguese at sea. This was something only the Mameluke sultanate of Egypt could provide. The Mameluke sultan had several Red Sea ports available (notably, Jeddah, recently expanded) where a fleet could be built. But, despite the entreaties of the Zamorin, the Venetian Republic, the Sultan of Gujarat and the overseas Arab merchant community, the Mameluke sultan had been slow to react to the Portuguese threat in the Indian Ocean. It was really only in 1503 or 1504, when his own treasury officers reported that the disruptive Portuguese activities were beginning to make a dent in the Mameluke treasury (dwindling revenues from customs dues on the spice trade and pilgrim traffic), that the Mameluke sultan was finally roused to action. Secret preparations began for the construction of a coalition fleet in the Red Sea ports, to drive the Portuguese out of the Indian Ocean.

In September/October 1504 (or perhaps 1503?), the Mameluke sultan Al-Ashraf Qansuh al-Ghawri of Egypt dispatched an embassy to Rome, angrily demanding that the pope reign in the Portuguese, threatening to mete out the same treatment on Christian pilgrims to the Holy Land as the Portuguese had been handing Muslim pilgrims to Mecca. The sultan's complaint was forwarded to Lisbon by a worried Pope Julius II. But it only served to alert King Manuel I of Portugal that the sleeping Mameluke giant had been awakened, that something large was afoot, and that the Portuguese had better secure their position in the Indian Ocean before it was too late.[1]

The Portuguese position was indeed precarious – not only in India, but also in East Africa. The Portuguese had an old reliable ally in Malindi (Melinde), but the stages up to Malindi were weak. The powerful city-state of Kilwa (Quíloa), which dominated the East African coast, was inherently hostile to the Portuguese interlopers, but had thus far restrained her hand for fear of reprisals. (Kilwa had been forced to pay tribute by Vasco da Gama in 1502). But should a serious Muslim fleet challenge the Portuguese in the Indian Ocean, Kilwa would likely take the opportunity for action. As putative overlord of the Swahili Coast, Kilwa could probably close down all the Portuguese staging points in East Africa, including the all-important Mozambique Island (the critical stop after the Cape crossing) and the attractive port of Sofala (the entrepot of the Monomatapa gold trade, which the Portuguese were trying to tap into). Mombasa (Mombaça) would only be too happy to overrun its neighbor and rival Malindi, depriving the Portuguese of their only ally in the region.

So the Almeida expedition of 1505, the 7th Armada to the Indies, had the double objective of securing the Portuguese position in India against Calicut and in East Africa against Kilwa, before the Egyptian-led coalition cobbled their naval strike force together.

Appointment of Almeida

The 7th Armada was to be an expedition like no other before: it was going to establish a Portuguese government in the Indian Ocean, a Viceroy of the Indies

This had been a long-gestating and controversial idea in the Portuguese court. When King John II of Portugal devised the plan of opening a sea-route to India, he thought primarily in terms of personal enrichment. An ambitious and centralizing monarch, John II saw wealth as a means to break the crown's dependence on the feudal nobility, and concentrate power in the king's hands. The spice trade was merely a means to build up the royal treasury. John II's successor, King Manuel I of Portugal, was a more traditional monarch, happy in the company of high nobles, with a more Medieval outlook, including an eagerness to spread religion and pursue 'holy war'.[2]

For the first few years of Manuel's reign, the India armadas had been largely handled by the 'pragmatic' party inherited from John II. They saw the India run largely as he had – a commercial venture – and tailored the missions accordingly. But the success of the early Portuguese armadas had now attracted other parties. The 'Medievalists' in the Portuguese court, notably Duarte Galvão, now wanted to give the India expeditions the glitter of a crusade, presenting it as the opening of a 'new front' in a holy war on Islam, a resumption of the old reconquista. Galvão openly romanticized about King Manuel personally conquering Jerusalem and even Mecca.[3]

The old pragmatists naturally balked at the prospect of turning their lucrative cash-making enterprise into a quixotic venture for holy glory. Court pragmatists like D. Diogo Lobo, Baron of Alvito, the powerful vedor da fazenda, fought hard to keep the India armadas from being diverted into messianic pursuits by Duarte Galvão's clique.

The decision to establish a Portuguese 'Vice-roy' of the Indies, to oversee all Portuguese establishments in the Indian Ocean, had been conceived as early as 1503. It represented something a victory for the Medievalists. In effect, it announced that the Portuguese would no longer be content to merely trade for spices, that they were going to establish a Christian state in the east, to spread religion, make alliances and launch a Holy War on the eastern flank of Islam. In Manuel & Galvão's vision, it would be a two-pronged Christian offensive that would converge on the Holy Land itself. The attack on the western flank was taken up by Manuel that very same year, with the resumption of expeditions against Morocco (Agadir, Mogador, etc.).

The establishment of a Portuguese state in India had a more practical reason: to help Portugal make formal treaties with Indian states. Portuguese India Armadas, organized by the Casa da India (the royal commercial trading house), had been visiting India yearly since Vasco da Gama's first arrival in 1498. But their powers were unclear. They had been operating largely as visiting merchant convoys, buying spices and returning home. Although the captain-majors of Portuguese India armadas claimed to be ambassadors for a distant King of Portugal, and delivered royal letters of communication, Indian potentates doubted whether these captains actually represented anyone at all. Many suspected they were simply self-aggrandizing private merchants and pirates, trying to extract favorable trade terms for themselves by falsely claiming some exalted authority, to be speaking on behalf of some foreign potentate. The treaties struck with the annual captains, different every year, and terms often changing, did not feel like proper treaties but just temporary agreements while they filled their hulls. The Zamorin of Calicut had at one point demanded to send ambassadors to the royal court of King Manuel I of Portugal, since he didn't believe the armada captains really had any authority to negotiate treaties in his name. So the establishment of a permanent Portuguese state authority in the Indian Ocean in 1505, a "Estado da India", with explicit political authority, and a permanent local governor, superior to the armada captains in India, able to control their behavior and enforce terms, was essential to win the trust of Indian rulers, and enable Portugal to negotiate and conclude binding inter-state treaties of trade and alliance.

The first designated vice-roy, the commander of the 7th armada, was decided around 1504 to be Tristão da Cunha. A powerful high noble, courtier and royal counselor of Manuel I, Cunha had sufficient pragmatic instincts to be acceptable to the older party (Cunha had participated in outfitting ships in previous armadas). However, in early 1505, Tristão da Cunha was struck by an affliction to his eyesight rendering him temporarily blind. As a result, the choice for his replacement fell upon Dom Francisco de Almeida.

D. Francisco de Almeida was a younger son of the D. Lopo de Almeida, Count of Abrantes. The Almeida family was one of the most powerful, resolute and vocal opponents of Manuel I of Portugal in these years, and the primary supporters of Manuel's main rival, D. Jorge de Lencastre. But Francisco had always been a bit of a black sheep in the Almeida family. In his youth, he entered into at least two conspiracies against King John II of Portugal (to whom the Almeidas were devoted), and was even exiled for a spell.

Francisco de Almeida's ambivalent loyalties might have been regarded by Manuel as a political opportunity. If he cultivated the cadet, Manuel might yet lure the rest of the Almeida family over to his side, or at least weaken their opposition. Francisco de Almeida, bubbling with ambition, seemed prepared to do anything to receive the appointment. In January 1505, he scandalously abandoned Lencastre's Order of Santiago to join Manuel's Order of Christ. He received his appointment letter from Manuel I shortly after, on February 27, 1505.

Manuel I designated D. Francisco de Almeida as captain-major of the 7th Armada, with the obligation to remain in India for three years. He would only be allowed to assume the title of 'Vice-Roy' upon the construction of four crown fortresses in India at Anjediva, Cannanore, Cochin and Quilon.[4]

In the prelude, Almeida outlined his plan to King Manuel I in modest terms, steering clear away from Medievalist fantasies. Almeida's plan was to only open a few critical coastal and island fortresses at strategic locations, just enough to allow the Portuguese navy to range over the length and breadth of the Indian Ocean, rather than attempt ruinous large territorial conquests. The king approved the plan and chose the locations of the fortresses himself.[5]

It is common to wonder why Vasco da Gama was overlooked for the position. Gama was available and, by royal letter, he was entitled to a say in Indies matters, so why wasn't he chosen for viceroy? In effect, he was just beaten to the prize. Like Almeida, Gama was connected to the opposition party, Santiago, etc., but had been too slow to switch over to the king's party and did not promise the king what he wanted to hear. Moreover, Almeida was of higher blood and patronizing the mighty Almeidas promised bigger political returns for the king than the lowly Gamas (even though the two families became connected after the marriage - in 1499 - of Vasco da Gama to Catarina de Ataíde, a first cousin of Francisco de Almeida). More pertinently, Gama's judgment was also questioned in whispers through the court. The 4th Armada that Vasco da Gama had commanded to India in 1502 had not been a success. He had failed to bring the Zamorin to terms and, more egregiously, the coastal patrol he left behind, under his uncle Vicente Sodré, had nearly cost the Portuguese their position in India. While the fault should be properly assigned to the Sodré brothers for dereliction of duty, there was a sense in the royal court that the patrol's failure was at least partly Gama's fault. He had insisted on the appointment of the Sodrés, he was their familiar and their superior, and could not have been wholly ignorant of their plans. Finally, Gama was a bit distracted – he was still trying to secure his hold on the granted town of Sines, and pestering the king to no end about it, with the result that Gama was not, at that moment, particularly welcome in Manuel's court.

The Fleet

The Seventh Armada was the largest Portuguese armada yet sent to India — 21 ships (or 22, if Bom Jesus is counted separately), carrying 1500 armed men with 1000 in crew and others. (The following list should not be regarded as authoritative; it is a tentative list compiled from various conflicting accounts.)

| Ship Name | Captain | Notes |

| Large ship (Nau) | ||

| 1.Bom Jesus | D. Francisco de Almeida | Uncertain if ship existed; could be nickname of S. Jerónimo |

| 1a. São Jerónimo | Rui Freire de Andrade | 400t, could be flagship instead of 1. Andrade designated to return. |

| 2. São Rafael | Fernão Soares | carrying German Hans Mayr; designated to return |

| 3. Lionarda | Diogo Correia | 400t, carrying German Baltazar Sprenger, designated to return |

| 4. Judia | Antão Gonçalves | alcaide of Sesimbra; namesake (prob. son) of Henry-era explorer designated to return |

| 5. Botafogo | João Serrão | 400t. Serrão might only be pilot, captain unknown. Serrão designated to remain in India. poss. carrying D. Álvaro de Noronha, new captain for Cochin. It is known that Serrão's brother Francisco Serrão and their cousin, the young Ferdinand Magellan went to India with this fleet, although uncertain on which ship.[6] |

| 6. Madalena | Lopo de Deus/Goes Henriques | Lopo Went as both captain and pilot. Prob. carrying D. Lourenço de Brito, future captain of Cannanore |

| 7. Flor de la Mar | João da Nova | 400t. Veteran admiral of 3rd Armada (1501), designated to take over India patrol |

| 8. São Gabriel | Vasco Gomes de Abreu | Abreu was designated for Red Sea patrol |

| 9. Concepão | Sebastião de Sousa | carrying D. Manuel Paçanha, future captain of Anjediva, flagship of 2nd squad |

| 10. Bella | Pêro Ferreira Fogaça | foundered near equator, future captain of Kilwa. |

| 11. Sant' Iago | Pêro de Anaia | 400t, future captain for Sofala, foundered in Tagus, did not depart; led separate Sofala squad later |

| Small Ships (navetas) | ||

| 12. São Miguel | Francisco de Sá/Fernão Deça | Killed at Mombasa. Passed to Rodrigo Rabello. |

| 13. Esphera | Felipe Rodrigues | |

| 14. unknown | Alonso/Fernão Bermudez | Castilian |

| 15. unknown | Lopo Sanchez | Castilian; ship lost near Quelimane. |

| Caravels | ||

| 16. unknown | Gonçalo de Paiva | scout of 1st Squad |

| 17. unknown | Antão Vaz | Sometimes confused with António do Campo (who did not sail this year). |

| 18. unknown | Gonçalo Vaz de Goes | left as patrol ship in Kilwa |

| 19. São Jorge | João Homem | Separated at Cape, rejoined at Malindi, Provoked Quilon massacre, ship passed to Nuno Vaz Pereira |

| 20. unknown | Lopo Chanoca | Separated at Cape, rejoined at Malindi |

| 21. unknown | Lucas da Fonseca/d'Affonseca | Separated at Cape, did not cross until 1506 with Sofala naus. |

There is conflict between various chroniclers over the exact composition, or the names of ships and captains. João de Barros reports 22 ships and 20 captains;[7] Castanheda says 15 carracks and 6 caravels, 20 captains; Gaspar Correia 8 large carracks (naus), 6 small ships (navetas), 6 caravels, and 21 captains; Relacão das Naos 14 carracks, 6 caravels, 22 captains.[8]

.jpg.webp)

The 11 large carracks (naus) were ships of 300-400t (or more), most designated to return. The small carracks (navetas) (150-250t) and caravels (under 100t) were designated to stay in the Indies in various patrol duties.

There is some confusion over the flagship of the fleet. Most sources suggest it was the São Jerónimo, but some claim it was the São Rafael. The confusion may be caused by the fact that Fernão Soares (São Rafael) was indeed designated to be the captain-major (capitão-mor) of the return fleet of early 1506. But, in the outward journey, it seems vice-roy Almeida was aboard the São Jerónimo. A few sources identify the flagship as Bom Jesus, but since a ship of this name is not given in most lists, that may just be a nickname for the S. Jeronimo.

Some ship names are repeated from earlier fleets: the São Jeronimo, known to be a carrack of large class (400t or more), may have been the same as the flagship of Vasco da Gama in the 4th Armada (1502). The Flor de la Mar, the renowned 400t beauty, and the Lionarda, were veterans of that same expedition.

There was significant private participation in the Seventh Armada. At least two of the ships, São Rafael and Lionarda, and very likely a third (the very flagship, São Jerónimo) were privately owned and outfitted by foreign merchants. German financiers, representatives of the powerful silver merchant families of Augsburg and Nuremberg, had begun arriving in Lisbon in 1500s, keen to enter into the Portuguese spice trade. They had been largely kept out of prior fleets, but with the crown now keen on assembling the largest armada possible for Almeida, the Germans finally secured contracts in late 1504.[9] A consortium of Welser and Vöhlin, represented by Lucas Rem (who had arrived in Lisbon in late 1503), sunk 20,000 cruzados in this expedition, another German consortium composed of Fuggers, Hochstetters, Imhofs, Gossembrods and Hirschvogels, entered with 16,000. An Italian consortium, primarily Genoese, headed by the expatriate Florentine financier Bartolomeo Marchionni, invested 29,400.[10] At least one ship, probably the Judia (alternatively, possibly the Botafago), was outfitted by native consortium headed by the Lisbon merchant Fernão de Loronha (by natural transcription error, the Judia is sometimes recorded as India).

The terms of private participation would become an item of contention. The private participants secured the crown's permission to send their own private factors to buy spices in India (rather than rely on the royal factor). But then, on January 1, 1505, after the contracts were signed and most of the money sunk, King Manuel I issued a decree requiring that henceforth all private participants, upon return, would sell their spice cargoes at fixed prices through the king's agents, rather than allow the merchants to sell it on the open market at their own discretion (that is, after paying the king's share, the Belem vintena and other applicable customs duties, some 30% of the cargo's value).[11] The private outfitters of the Seventh Armada would launch a legal suit, claiming the decree should not apply retroactively to them.

The foundering of Pêro de Anaia's Sant'Iago (sometimes referred to as the Nunciá) in the Tagus harbour upon departure, prompted the immediate assembly of another six-ship fleet that set out a month later. Although it never caught up with Almeida's fleet, it is sometimes considered part of it. Pêro de Anaia was responsible for erecting a fortress in Sofala, and then, retaining two ships for a local patrol, to send the remaining four on to India to place themselves under D. Francisco de Almeida.

| Ship Name | Captain | Notes |

| Naus | ||

| 22. uncertain | Pêro de Anaia | flagship, captain of Sofala; Ship later taken by Paio Rodrigues de Sousa to India in 1506. |

| 23. Espírito Santo | Pedro Barreto de Magalhães | 400t, found remnant of Sanchez crew at Quelimane. Designated to go to India, but ran aground on Kilwa banks. |

| 24. Santo António | João Leite | Ship taken by Pedro Barreto de Magalhães to India in 1506. |

| Caravels | ||

| 25. São João | Francisco de Anaia | Designated to patrol in Sofala. Later lost near Mozambique. |

| 26. unknown | Manuel Fernandes (de Meireles) | Factor for Sofala. Ship taken to India by Jorge Mendes Çacoto in 1506 |

| 27. São Paulo | João de Queirós | Designated to patrol in Sofala. Later lost near Mozambique. |

Finally, a third small two-ship expedition was sent out from Lisbon in September (or November) 1505, under the command of Cide Barbudo. This was on a search-and-rescue mission to seek out the fates of three ships of earlier armadas thought to have been lost in South Africa. It was then to check up on the existing fortresses of the Indian Ocean and deliver letters from King Manuel I to the viceroy Almeida with further instructions.

| Ship Name | Captain | Notes |

| 28. Julioa | Cide Barbudo | nau, went on to India in 1506. |

| 29. uncertain | Pedro Quaresma | caravel; remained behind in Sofala. |

So, overall, 29 ships left Portugal in 1505 for the Indian Ocean: 21 under Almeida, 6 under Anaia, and 2 under Barbudo.

The Mission

The mission of the 7th fleet was nothing short of permanently securing the Portuguese position in the Indian Ocean, before the imminent Egyptian-led coalition fleet set to sea. That meant doing whatever was necessary to knock out the main regional threats to Portuguese power – specifically, the city-states of Calicut (India) and Kilwa (Africa). Simultaneously, the fleet should shore up regional Portuguese allies – Cochin, Canannore and Quilon in India, and Malindi and Sofala in Africa – and establish and garrison forts at the key staging posts (e.g. Angediva) to ensure the Portuguese navy could operate across the Indian Ocean.

As noted, D. Francisco de Almeida was given commissions as captain-major of the 7th Armada upon departure, with permission to assume the title of 'Viceroy of the Indies' (and associated privileges) only upon the erection of the fortresses.

Accompanying Almeida were several other nobleman, designated to serve as captains of the fortresses to be established. As per King Manuel I's instructions (regimento), these should be, in order:[12] (1) Pêro de Anaia for the fort in Sofala, (2) Pêro Ferreira Fogaça for the fort in Kilwa, (3) Manuel Paçanha for the fort of Anjediva island and/or, if a fortuitous location could be found, a fortress to be established at the mouth of the Red Sea; (4) D. Álvaro de Noronha for the already-existing fort of Cochin, (5) D. Lourenço de Brito for a fort to be erected in Quilon (not, as it ultimately turns out, Cannanore).

The fleet also carried several figures for the central government in Cochin. The king arranged for a corps of one hundred halberdiers to serve as the vice-roy's personal guard, largely to allow Almeida to impress and match the ceremonial pomp of Indian princes. At Almeida's request, the King Manuel appointed the doctor of law Pêro Godins to serve as jurist (ouvidor) and legal adviser to Almeida. In addition to the vice-roy's private secretaries, Manuel decided (without consulting Almeida) to appoint Gaspar Pereira as an all-around secretary of state for Portuguese India ('Secretário da Índia').[13] The Secretary's exact authority and functions, however, were not clearly defined, with the result that the ambitious Pereira would try to carve out a large share of the government of Portuguese India for his office and clash frequently with Almeida.

The 6th Armada of 1504 had left Manuel Teles de Vasconcelos as captain of a small three (or four) ship India coastal patrol. The ten smaller ships (navetas and caravels) coming with the Seventh Armada were to be distributed between Africa and India. Without Almeida's knowledge, Manuel I gave João da Nova (the old Galician admiral of the 3rd armada of 1501) a secret commission to take over the Indian coastal patrol from Manuel Teles. This infringed on Almeida's assumption that, as vice-roy, he had the right to fill that appointment with his own candidate – his son, Lourenço de Almeida, who was coming along as a passenger. Vasco Gomes de Abreu had a commission to head a patrol off Cape Guardafui, with instructions prey on Arab shipping around the mouth of the Red Sea and keep an eye out for the Egyptian fleet.

The Indian patrol is instructed to sail the length of the Indian coast up to Cambay and beyond, offering peace to any ruler who desires it in return for tribute. The East African patrols operating out of Sofala and Kilwa are to prey on all Muslim shipping (except Malindi), and to seize their cargoes, esp. of gold (under the excuse of the general 'holy war' between Muslims and Christians.) Almeida is also under instructions to collect the annual tribute imposed in 1502 from Kilwa, and to attack the city if refused. He is also (unlike his predecessor) authorized to make peace with the Zamorin of Calicut, but only if sought by the Trimumpara Raja of Cochin and only on the condition that the Zamorin expel all expatriate Arabs ('Moors of Mecca'), from his cities and ports.

Part of the expedition was purely commercial, a conventional spice run. The S. Jeronimo, S. Rafael, Lionarda, Judia and/or Botafogo, were (at least in part) owned and outfitted by private merchants, the other large naus owned and outfitted by the royal Casa da India. In all, the eleven large carracks (naus) that set out with the Seventh Armada were expected to return immediately. Almeida had instructions to organize the return voyage of the merchant ships in groups of three, as they became filled with spices. Fernão Soares (São Rafael) was pre-designated as captain-major of the first return fleet.

Finally, Almeida was also instructed to begin arrange expeditions "to discover Ceylon and Pegu and Malacca, and any other places and things of those parts."[14]

The foundering of Pêro de Anaia's ship (Sant'Iago) at the mouth of the Tagus upon departure led to a slight revision of the plans. A new fleet of six ships under Anaia was quickly assembled and set out for Sofala separately, carrying material to build a fortress there. Two of those ships would remain behind on local African coastal patrol under Anaia's son Francisco de Anaia, while the remaining four were to be sent on to India for a spice run.

Finally, the end-of-year ships of Cide Barbudo and Pedro Quaresma, after conducting their search-and-rescue mission, were to check up on the fortresses and deliver letters with further instructions from the king to the fortress captains and viceroy Almeida.

Outward Voyage

March 25, 1505 – The 7th Armada sets off from Lisbon. Immediately at departure. Pêro de Anaia's ship, the Sant'Iago, founders at the mouth the Tagus, and has to be hauled back into Lisbon harbour. Rather than wait for it to be repaired, it was decided to allow Almeida to press on. A new squad of six ships will be assembled around Anaia, and depart later.[15]

April 6, 1505 7th Armada sails through Cape Verde and makes a brief stop at Porto de Ale (Senegal) to resupply.[16] Hearing of the massive India squadron, a local Wolof chieftain appears by the shore with his entourage. João da Nova is dispatched to parlay with the king and secures supplies, including fresh cattle beef, for the fleet.[17]

April 25, 1505 Departing Senegal, Almeida splits the armada into two separate squads. He assembles a fast squadron, composed of two naus, the ships of Sebastião de Sousa (Concepção) and Lopo Sanchez (unknown name), plus five caravels. Almeida appoints nobleman D. Manuel Paçanha (or Pessanha – a descendant of the famous Luso-Genoese admiral)) as admiral of the fast squadron (it is said Almeida gave Paçanha that honor on the erroneous assumption that King Manuel had secretly designated Paçanha as Almeida's successor.)[18] The other slower squadron, to be led by Almeida himself, is composed of the other 12 naus and the remaining one caravel (that of Gonçalo de Paiva, which is to serve as forward lamp and scout for the slower ships).

May 4, 1505 Around the equator, one of the ships in Almeida's squadron, the Bella (under captain Pêro Ferreira Fogaça) springs a leak and begins to founder.[19] The crew and cargo are distributed among other ships. Almeida's squadron is now reduced to 11 naus plus the caravel of Gonçalo de Paiva. The two squadrons at sea at this stage are summarized in the following table (fl = flagship, all large naus, except nta = naveta, cv = caravel)

| First Squadron (Francisco de Almeida) | Second Squadron (Manuel Paçanha) |

| 1. Rui Freire de Andrade (São Jerónimo, fl) | 1. Sebastião de Sousa (Concepcão, fl) |

| 2. Fernão Soares (São Rafael) | 2. Lopo Sanchez (nta) |

| 3. Diogo Correia (Lionarda) | 3. Antão Vaz (cv) |

| 4. Antão Gonçalves (Judia) | 4. Gonçalo Vaz de Goes (cv) |

| 5. João Serrão (Botafogo) | 5. João Homem (São Jorge , cv) |

| 6. Lopo de Deus (Madalena), | 6. Lopo Chanoca (cv) |

| 7. João da Nova (Flor de la Mar) | 7. Lucas da Fonseca (cv) |

| 8. Vasco Gomes de Abreu (São Gabriel) | |

| 9. Francisco de Sá (São Miguel, nta) | |

| 10. Felipe Rodrigues (Esphera, nta) | |

| 11. Fernão Bermudez (nta) | |

| 12. Gonçalo de Paiva (cv) | |

May 18, 1505 Pêro de Anaia sets out with six-ship fleet (3 naus, 3 caravels), which can be considered as a third squadron of the Seventh Armada. This squadron is destined for Sofala. (See Anaia's expedition to Sofala)

June 26, 1505 – Almeida's squadron doubles the Cape of Good Hope with some difficulty, meeting a violent storm on the other side, during which some ships are separated.. He proceeds into the Mozambique Channel and lands at the Primeiras islands (off Angoche), where he repairs his masts and awaits the missing ships of his squadron. During this interlude, Almeida dispatches the caravel of Gonçalo de Paiva up to the Portuguese factory on Mozambique Island to collect any letters left by any Portuguese ships returning from earlier expeditions, which might contain the latest news about the situation in India.

July 18, 1505 After a couple of weeks stay on the Primeiras, Almeida's squadron is reassembled. Of the 12 ships in his squadron, Almeida finds himself missing only two ships – João Serrão (Botafogo) and Vasco Gomes de Abreu (São Gabriel). Hearing of neither of them, nor of Gonçalo de Paiva (still on errand to Mozambique), nor, for that matter, any news of the squadron of Manuel Paçanha by July 18 Almeida decides to press on and sets sail north. Skirting past Mozambique, Almeida dispatches the naveta of Fernão Bermudez to the island to check on what has been delaying Paiva, while he proceeds with the rest of the fleet on towards Kilwa.

Manuel Paçanha's squadron is considerably less lucky in the Cape crossing. Of the seven ships, only three manage to stay together – the nau of Sebastião de Sousa (Conceipção) and the caravels of Antão Vaz and Gonçalo Vaz de Goes. The remaining four ships are scattered. Their fates, as was later discovered:

- The caravel of João Homem followed a very wide course around the Cape and stumbled upon an unknown small group of South African islands (which he promptly named 'Santa Maria da Graça', 'São Jorge' and 'São João').[20] Then, somewhere on the other side of the Cape (possibly at Mossel Bay), Homem encounters the caravel of Lopo Chanoca, and they decide to proceed together. Caught by fast currents in the Mozambique Channel, the pair are speedily swept together far up the East African coast (overtaking everybody else) to a small shoal-ridden bay just south of Malindi.[21] Their ships damaged, they decide to anchor there, and walk overland to Malindi, to get help from the other ships. But as no one is there yet, they decide to wait.[22]

- The caravel of Lopo Sanchez meets a more tragic fate. After crossing the Cape, it miscalculates the channel entry and runs aground somewhere around Cape Correntes. The ship is thoroughly shattered on the shoals. Lopo Sanchez orders the crew to rebuild the caravel, but about half the crew (some 60) refuses to obey. The 'sea lawyers' among them argue that the loss of the caravel has dissolved the authority of the captain over the crew (Sanchez's foreign (Castilian) nationality does not help his case.) The mutinous segment of the crew, some 60 sailors, decide to march overland to Sofala. But without supplies or clear directions, they have a harrowing journey. Most of them die on the way – from disease, hunger, exposure and clashes with the locals; one group is captured and thrown into a jail in Sofala; another finds its way to the outskirts of Quelimane. Nothing is known of the crew that stayed behind with Sanchez rebuilding the caravel. It is assumed they set sail again, and perished at sea.

- The caravel of Lucas da Fonseca (d'Affonseca) simply lost its bearings during the Cape crossing. No one is exactly sure where it roamed. It eventually finds its way to Mozambique Island, but too late – the rest of the Seventh Armada had already departed and the monsoon winds have reversed for the season. Fonseca's caravel will be forced to linger around Mozambique, and only cross the next year (1506), with the Sofala naus.

Capture of Kilwa, Fort Sant'Iago

July 23, 1505 – Francisco de Almeida arrives on the island-state of Kilwa (Quíloa) with only eight ships. Intent on collecting the annual tribute (imposed 1502) owed to the king of Portugal, Almeida fires his guns in salute, but, after receiving no reply for the courtesy, sends João da Nova to lead inquiries into why. Messages are shuttled back and forth between Francisco de Almeida and Kilwa's strongman ruler Emir Ibrahim (Mir Habraemo), the latter of whom seems to be doing his utmost to avoid a meeting. At length, Almeida decides to attack the city. Almeida lands 500 Portuguese soldiers in two groups, one under himself another under his son, Lourenço de Almeida on either side of the island, and march on the Emir's palace. There is little opposition – Emir Ibrahim flees the city, along with a good part of his followers.[23]

Once inside, Almeida sets about organizing the political settlement for Kilwa. As Emir Ibrahim (Mir Habraemo) was an usurper, a minister who had recently overthrown and murdered the rightful sultan al-Fudail (Alfudail, see Kilwa Sultanate), Almeida decides to impose his own ruler. His choice falls on Muhammad ibn Rukn ad Din (Arcone or Anconi), a wealthy Kilwan noble who had earlier promoted a Portuguese alliance and more recently, during the message phase, secretly entered into contact with João da Nova. Muhammad Arcone accepts the position and agrees to honor the tribute to Portugal. Almeida even produces a golden crown (intended for Cochin) to conduct a formal coronation ceremony. But Muhammad Arcone, not being of royal blood, knows it is constitutionally improper for him to assume the Kilwa Sultan's throne. As a result, he insists on appointing Muhammad ibn al-Fudail (Micante, son of the late sultan murdered by Emir Ibrahim) as his successor, claiming he, Arcone, is only holding the throne 'temporarily'.

That is good enough for Almeida. The Portuguese set about erecting a fortress in the city, which they name Fort Sant'Iago (or São Thiago, now Fort Gereza) on Kilwa island.[24] It is the first Portuguese fort in East Africa. Almeida installs a Portuguese garrison of 550 (half his men?) in Kilwa, under the command of Pêro Ferreira Fogaça (former captain of the shipwrecked Bella), with Francisco Coutinho as magistrate. Fernão Cotrim is appointed factor, with instructions to do what he can to tap into the inland gold trade.[25]

While the final details are being arranged in Kilwa, Gonçalo de Paiva and Fernão Bermudes finally arrive from their side-trip to Mozambique Island. They bring the letters left behind by Lopo Soares de Albergaria of the returning 6th Armada, with the latest news of conditions in India. It is probably from Lopo Soares's letters that Almeida learns of the recent Mombasan attack on Portuguese-allied Malindi (1503, broken up by Ravasco and Saldanha)

While in Kilwa, one of the missing ships of Almeida's squadron, João Serrão (Botafogo) arrives in Kilwa harbour. But Abreu's São Gabriel is still missing, and there is still no news of any of the ships of Manuel Paçanha's squadron.

Wary of the monsoon timing, Almeida makes up his mind to move on. He leaves behind a copy of his itinerary in Kilwa, so the missing ships can catch up with him. He also leaves behind instructions for Manuel Paçanha to leave one of his caravels in Kilwa to serve as a local patrol. The rest of the fleet leaves Kilwa on August 8.

Sack of Mombasa

August 13, 1505 – Almeida's fleet menacingly anchors before the island-city of Mombasa (Mombaça), the old rival of Portuguese-allied Malindi. The caravel of Gonçalo de Paiva, which had gone forth to sound the harbour, is fired upon by Mombasan coastal cannons (apparently salvaged from earlier Portuguese ship wrecks) [26] Return fire silences the cannons.

Almeida sends out an ultimatum to Mombasa, offering peace in return for vassalship and tribute to Portugal. This is rejected out of hand, replying that the "warriors of Mombasa are not the hens of Kilwa". Having heard of the attack on Kilwa, Mombasa had already mobilized its forces and hired large numbers of Bantu archers from the mainland, who were already deployed around the city (and more soon expected).

Almeida initiates a shore bombardment to little effect on the defended city. A Portuguese raid on the docks (led by João Serrão) and another at the central beach (led by Almeida's son Lourenço) are thrown back, yielding up the first Portuguese casualties.

Frustrated, Almeida lays out a different plan of attack. At dawn the next day, young Lourenço once leads a large force on the central beach again, while simultaneously, a smaller force in a rowboats sneaks into the dock area and sets about raiding noisily there. It looks like a repeat of previous day's attacks, and Mombasan defenders are drawn to those two points. But it is a mere feint, allowing Francisco de Almeida himself to sail around and land the bulk of his assault force in a relatively undefended part of island-city.

Unlike at Kilwa, the Mombasans put up a fierce fight in the narrow streets of the city. But eventually Almeida reaches and seizes the sultan's palace (albeit finding it empty). The fighting dissolves soon after as the Bantu archers begin to withdraw back to the mainland, and the Mombasan population tries to flee with them. Great numbers of people are cut down in flight by Portuguese musket and crossbow perched on vantage points around the sultan's palace.

In the aftermath, Almeida gives the emptied city over to the sack by the Portuguese troops. Some 200 Mombasan captives (mostly women and children) are taken as slaves by the Portuguese.[27]

Although the plunder is plentiful, the Portuguese have also taken significant casualties – at least 5 are dead, and numerous wounded. Among the slain are Francisco de Sá (or Fernão Deça), captain of the caravel São Miguel. His ship passes to the knight Rodrigo Rabello (or Botelho).

Unlike Kilwa, Almeida has no intention of holding Mombasa. But he is kept for a while in harbour by difficult winds. During this interlude, the last remaining ship of Almeida's squadron, Vasco Gomes de Abreu (São Gabriel) hobbles into Mombasa harbour, with a broken mast. Still no news of the Paçanha squadron, however.

Unable to visit Malindi himself, Almeida dispatches two captains, Fernão Soares (São Rafael) and Diogo Correia (Lionarda), to Malindi to pay his respects to the sultan and report the raid on Mombasa. They return shortly after, bringing not only fresh supplies and the Sultan of Malindi's congratulations and rewards, but, much to Almeida's surprise, also Lopo Chanoca and João Homem, captains of two of the caravels of Paçanha's squad. They report how they were swept into a bay near Malindi and made their way overland into the town, where Almeida's captains found them. Almeida orders the two caravels to be picked up from the bay and joined to his squadron for the Indian Ocean crossing.

August 27, 1505 Unwilling to wait any longer for the rest of the Paçanha squadron, Almeida sets sail on the Indian Ocean crossing with the 14 ships currently under his command.

Almeida in India

Fort São Miguel of Anjediva

September 13, 1505 – Almeida alights on the Indian coast at the island of Anjediva (Angediva, Anjadip). As per the orders received in Lisbon, Almeida immediately begins the construction of a Portuguese fortress on the island – Fort São Miguel of Angediva, principally with local stone and clay. He also erects the Church of Our Lady of Springs (Nossa Senhora das Brotas) (depending on exactly when the Cochin church was erected, this might very well be the first Roman Catholic church in Asia.)

During the construction, Almeida dispatches two caravels under João Homem to speed down the coast and visit the Portuguese factories at Cannanore, Cochin and Quilon to announce the 7th Armada's arrival in India. Another two caravels, those of Gonçalo de Paiva and Rodrigo Rabello, are dispatched on a piratical mission in the vicinity, to seize any Calicut-bound vessels.

Anjediva island lies around the frontier between the large enemy states of Muslim Bijapur and Hindu Vijayanagar. As a result, the area is a tense zone, littered with fortifications and pirates. Noticing that a new borderland fort was being erected on the mainland, Almeida dispatches a well-armed squadron under his own son, Lourenço de Almeida, to inspect it and ensure it was not going to be a threat to Anjediva.

This gesture (and news of the fate of Kilwa & Mombasa) prompts the governors of Cintacora[28] and Onor (Honnavar) to quickly dispatch emissaries to Almeida at Angediva, with gifts and promises of a truce with the Portuguese.

Late September/Early October – During the construction period, the remainder of Manuel Paçanha's Second Squadron – now reduced to two ships, Sebastião de Sousa's Concepção (carrying Paçanha) and Antão Vaz's caravel – reaches Angediva. As per the instructions Almeida left back in Kilwa, Paçanha had left his third ship, Gonçalo Vaz de Goes's caravel, on patrol in Kilwa. Naturally Paçanha is delighted to find two of his missing caravels – João Homem and Lopo Chanoca – are safely with Almeida, but there is still no news of the remaining two – Lopo Sanchez (aground near Quelimane) and Lucas da Fonseca (by now probably safely in Mozambique, but the monsoon season too late to allow him an ocean crossing)

Construction finished, Almeida appoints Manuel Paçanha as captain of Fort São Miguel of Anjediva, with a garrison of 80 troops, a galley and two brigantines (acquired locally?), under the command of João Serrão. He also leaves behind a factor Duarte Pereira.

Raid on Onor

October 16, 1505 As Almeida's fleet sets out of Angediva, he decides to take another look at Onor (Honnavar), at the mouth of the Sharavathi River. Onor was the homebase of the Hindu corsair known as Timoja (or Timaya), who had caused some trouble to earlier armadas, and whom Almeida feared might yet cause trouble for Anjediva.

Almeida believes his suspicions are confirmed when he sees a significant number of Arab ships, alongside Timoja's own, in Onor harbour. Almeida accuses Onor's rulers of breaking the proffered truce and orders an attack on the port city. Resistance is fierce, but the Portuguese manage to sack and burn the harbour and break into the city. As they approach the palace, the governor pleads for peace. Almeida, who had been wounded in the process, suspends the fighting.

In the aftermath, the corsair Timoja and the governor of Onor (a vassal of the Vijayanagara Empire)[29] agree to swear an oath of vassalage and promise not to molest the Portuguese in Anjediva.

Fort Sant'Angelo of Cannanore

October 24, 1505 – From Onor, Francisco Almeida sails south to Cannanore and visits the old Portuguese factory. With the assistance of the old factor Gonçalo Gil Barbosa, he secures permission from the Kolathiri Raja of Cannanore to build a Portuguese fort in the city.

[Timing is a bit difficult to determine. Ferguson (1907: p. 302) suggests that it was begun soon after their arrival in October 1505, but Gaspar Correia says it was only begun in May, 1506. As, according to Damião de Góis (p. 150), Almeida's regimento did not actually specify the construction of a fort in Cannanore, but rather of a fort in Quilon, it is likely permission was not sought until after the Quilon events outlined below, that is, around November 1505.]

Upon the completion of Fort Sant' Angelo of Cannanore, Almeida hands it over to the captain pre-designated originally for Quilon, D. Lourenço de Brito (a high noble, apparently a cup-bearer of King Manuel I), and a new factor Lopo Cabreira (replacing the long-serving Gonçalo Gil Barbosa) and a certain Castillian nobleman known as 'Guadalajara' as magistrate (alcaide-mor) of Cannanore.[30] Almeida leaves Brito with a garrison of 150 men and two patrol ships, the navetas of Rodrigo Rabello (São Miguel?) and Fernão Bermudez.[31]

At this point, having erected three fortresses (Kilwa, Anjediva, Cannanore), D. Francisco de Almeida formally opens the seal on his credentials and assumes the title of "Viceroy of the Indies", formally inaugurating his three-year term as the first governor of Portuguese India.

While in Cannanore, Almeida receives an embassy from Narasimha Rao (called Narsinga by the Portuguese), the ruler of Vijayanagar, the Hindu empire in south India, with a proposal for a formal alliance between the Portuguese and Vijayanagar empires (to be cemented by a royal marriage).[32] Having recently acquired a small stretch of the Malabar Coast around Bhatkal (Batecala), Narasimha Rao is probably anxious to ensure the Portuguese do not molest the importation of warhorses from Arabia and Persia, so essential for his armies.

Quilon Massacre

October 1505 – While Almeida is busy in Onor and Cannanore, the advance caravel of João Homem arrives in Quilon (Coulão, Kollam), right into the middle of a quarrel between the local Portuguese factor António de Sá and the regents of Quilon. De Sá had been fruitlessly trying to persuade the Quilon authorities to freeze out a group of Muslim spice merchants that had recently arrived from Calicut, but to no avail. Seeing Homem's caravel arrive in harbour, de Sá quickly persuades the captain to assist him in a hare-brained scheme to board the Muslim ships in harbour and cut down their masts and sails. Homem readily agrees, and this is swiftly done, much to the shock of the Quilon authorities, whose orders not to molest the ships were blatantly ignored.

As soon as Homem sets sail out of Quilon harbour to rejoin Almeida, an anti-Portuguese riot erupts in Quilon. The Portuguese in the city, including the factor and his assistants barricade themselves in a local Syrian Christian church – but the church is burned down by the mob and the Portuguese are massacred.

October 30, 1505 – Leaving Cannanore, Almeida proceeds to Cochin. But immediately upon arrival, Almeida receives the dramatic news of the Quilon massacre, and the provocative role of João Homem in the events. The furious Almeida demotes João Homem, and passes his caravel, the São Jorge, over to a new captain Nuno Vaz Pereira.[33]

Hoping to mend relations, Almeida immediately dispatches an expedition to Quilon under his 20-year-old son Lourenço de Almeida, with three naus and three caravels, under instructions to pretend as if nothing has happened, and hopefully negotiate a resolution. But seeing the approach of the Portuguese squadron, the city of Quilon rallies its defenses and prevent the Portuguese from disembarking. Lourenço limits himself to bombarding the town and burning down the (mostly Calicut-owned) merchant ships in Quilon harbour, before returning sullenly to Cochin.

Quilon, one of the three principal Portuguese factories and allies in India, is now lost to the Portuguese. It is a tremendous blow, as Quilon, by its proximity to Ceylon and points east, had the best spice markets of the three. There is a strong likelihood that the construction of Fort Sant'Angelo of Cannanore (see above) really only began now, after Quilon (the original fort destination) was no longer an option.

Coronation in Cochin

December 1505 – In the meantime, back in Cochin, Almeida reinforces Fort Manuel (erected in 1503) at Cochin, placing the garrison under D. Álvaro de Noronha, the new captain of Cochin (relieving Manuel Telles de Vasconcelos, who came with the 6th Armada in 1504). As the old factor Diogo Fernandes Correia is set to return to Lisbon, Almeida elevates Correia's long-serving assistant, Lourenço Moreno, as the new factor of Cochin.[34]

Almeida produces the golden crown dispatched by Manuel I of Portugal as a gift for his loyal ally, the Trimumpara Raja of Cochin. But the old Trimumpara seems to have since abdicated by this time, so Almeida uses the golden crown in a formal coronation ceremony of his successor, whom Barros calls Nambeadora, but probably the same person as Unni Goda Varda (Candagora) as King of Cochin, formally dissolving whatever remaining allegiance he might owe to the Zamorin of Calicut.[35]

Anaia in Sofala, Fort São Caetano

September 4, 1505, Pêro de Anaia's six-ship Sofala fleet ('Third Squadron') doubles the Cape of Good Hope, also with some difficulty. But it eventually anchors in Sofala harbour. One of his ships finds, near Quelimane, five famished half-dead survivors of Lopo Sanchez's caravel, with their tale of woe.

Pêro de Anaia secures an audience with the elderly blind sheikh Isuf of Sofala (Yçuf in Barros Çufe in Goes). Although formerly a vassal of the Kilwa Sultanate, Isuf had been trying to chart an independent course, and had already signed a commercial treaty in 1502 with Vasco da Gama (4th Armada). Anaia now requests Isuf's permission to establish a permanent Portuguese factory and fortress in the city.

News of Almeida's attacks on Kilwa and Mombasa persuade the Isuf that a similar fate might await Sofala if he shows any sign of recalcitrance, so the deal is struck. As a sign of goodwill, Isuf hands over to Anaia another twenty Portuguese survivors of the Lopo Sanchez caravel he had collected.[36]

Construction immediately proceeds on the Portuguese Fort São Caetano in Sofala. As per their credentials, Pêro de Anaia assumes command as 'captain-major' of the fort of Sofala and Manuel Fernandes (de Meireles?) as factor.

Barbudo's search-and-rescue mission

In September (or November[37]) 1505, the ships of Cide Barbudo (nau Julioa) and Pedro Quaresma (caravel of uncertain name) left Lisbon, carrying instruction letters from King Manuel I of Portugal for Anaia in Sofala and Almeida in India.

But before delivering these letters, the Barbudo and Quaresma were instructed to conduct a search and rescue operation on the South African coast. They were looking for three missing ships of the earlier armadas lost around Cape Correntes – specifically, the ships of Francisco de Albuquerque and Nicolau Coelho (both of the 5th Armada (1503)) and the ship of Pêro de Mendonça (of the 6th Armada (1504)).

The two rescue ships spent the next few months scouring the length of the South African coast, from the Cape of Good Hope to Natal. They found what seemed like the burnt hull of Pêro de Mendonça's ship near Mossel Bay, but no survivors. There were no traces of the other two ships.

Return Fleets

As viceroy, D. Francisco de Almeida is to remain in India for a three-year term; but the large ships of the 7th Armada are supposed to return to Lisbon with spice cargoes. Although the Quilon factory is now closed to them, the Portuguese ships nonetheless manage to find enough spices at Cannanore and Cochin (and from piracy) to begin returning.

Almeida has ten large naus in India – nine that came with him, and one left behind by the 6th Armada. The instructions drafted in Lisbon recommended Almeida send them back in groups of three as they become loaded.

January 2, 1506 – 1st Return Fleet – The first return fleet is ready to sail out of Cochin. Although there is some variation in the chronicles, it seems it is composed of five ships under the overall command of Fernão Soares:[38]

- 1. São Rafael – Fernão Soares

- 2. São Jerónimo – Rui Freire de Andrade

- 3. Judia – Antão Gonçalves

- 4. Concepção – Sebastião de Sousa

- 5. Botafogo – Manuel Telles de Vasconcelos

All are taken back by the same captains who brought them, with the exception of the Botafogo, which is being taken back by the relieved Cochin captain Manuel Telles (installed by 6th Armada in 1504). The Botafogo's original captain, João Serrão, stays behind in India, in command of a caravel of the Indian coastal patrol. Notice that of this fleet, two ships are German-owned (São Rafael and São Jerónimo), one is owned by Fernão de Loronha (prob. the Judia, alternatively the Botafogo), and two are owned by the crown (Concepção, and Botafogo/Judia – whichever one Loronha doesn't own).

January 21, 1506 – Second Return Fleet A couple of weeks after the first, the second return fleet set sail out of Cannanore, three ships under the overall command of Diogo Correia (Lionarda – the third German ship). This fleet is carrying back the two old factors, Gonçalo Gil Barbosa of Cannanore (originally installed in Cochin by Second Armada in 1500) and Diogo Fernandes Correia of Cochin (installed by 4th Armada in 1502 – not to be confused with the captain of the fleet).

- 6. Lionarda – captain Diogo Correia

- 7. Madalena – possibly captained by Lopo de Deus; carries ex-factor Diogo Fernandes Correia

- 8. uncertain (old 6th Armada nau) – captain also uncertain; Carrying ex-factor Gonçalo Gil Barbosa

February 1506 Third Return Fleet Finally, the third Return fleet sets out. It is composed of two ships only, carrying D. Francisco de Almeida's official report to King Manuel I and a baby Indian elephant.

- 9.São Gabriel – Vasco Gomes de Abreu

- 10. Flor de la Mar – João da Nova

According to his instructions, both Vasco Gomes de Abreu and João da Nova should have remained on patrol duty. But Almeida cancelled Abreu's appointment to patrol the Red Sea, with the justification that it was impractical until a permanent Portuguese base was established in that area. Almeida edged out João da Nova, who had a commission to take over the Indian coastal patrol, by noting that Nova's ship, the Flor de la Mar, a 400t+ behemoth, was useless as an Indian patrol ship. It wouldn't be able enter the Vembanad lagoon or any of the Kerala backwaters. Almeida offers Abreu and Nova the option to remain in India themselves and sending their ships back under other captains. Both Abreu and Nova elected to return to Lisbon.

As a result, Almeida is left with around 9 or 10 small naus/caravels on coastal patrol in India without a patrol captain. In his capacity as viceroy, Almeida appoints his own energetic son, Lourenço de Almeida, as capitão-mor do mar da India, captain-major of the seas of India.

Arrival in Lisbon

The three return fleets arrive at different times in Lisbon in 1506, with different incidents.

May 23, 1506 – First Return Fleet under Fernão Soares arrives in Lisbon, to much sensation (partly for having arrived so quickly, partly because it was primarily well-loaded private ships, generating a lot of correspondence back to Germany and Italy). One of the ships, the Botafogo under Manuel Telles, who got separated earlier, will arrive in June. Another significant note is that the return fleet of Fernão Soares is said to have charted a homeward route east of Madagascar (ilha de São Lourenço). This makes it the first time the outer route from the East Indies has been used on a return journey and possibly the first time the east coast of Madagascar was sighted and confirmed to be an island.[39]

November 15, 1506 – Second Return Fleet under Diogo Correia arrives in Lisbon. However, its third ship, the Madalena of Lopo de Deus, is delayed for repairs in Mozambique Island and will arrive only in January 1507.

December 1506 – Third return fleet arrives in Lisbon – actually, only nau São Gabriel of Vasco Gomes de Abreu, carrying Almeida's official report and the baby elephant. João da Nova's Flor de la Mar encountered problems near Zanzibar, where he is forced to stay for eight months for repairs. Nova will not return to Lisbon, but be picked up in February 1507 in Mozambique and annexed by the outbound 8th Portuguese India Armada of 1506.

Naturally, all three return fleets arrive too late to influence the outfitting of the next armada, the 8th India Armada, which set out under Tristão da Cunha in April 1506. Although scheduled to arrive in India that August, the 8th Armada will miss the monsoon winds and be forced to winter in Africa, arriving only in 1507.

Aftermath

The 7th Armada of D. Francisco de Almeida placed the Portuguese in a strong position in the Indian Ocean. The Portuguese now have five fortified strongpoints in the Indian Ocean: Kilwa and Sofala in Africa, and Anjediva, Cannanore and Cochin in India. A new Portuguese state had been erected in the Indian Ocean.

By and large, it had been a successful armada. Three new forts were erected, a couple of potential enemies knocked out (Kilwa, Mombasa), and the return fleets brought back substantial cargoes of spices.

But the seemingly smooth operation quickly developed wrinkles in 1506, as serious problems emerged in Cannanore, Anjediva, Sofala and Kilwa.

| City | Ruler | Establishment | Captain | Factor | Patrol Captain |

| 1.Sofala (Cefala) | sheikh Isuf | Fort São Caetano (est. 1505) | Pêro de Anaia (? men) | Manuel Fernandes de Meireles | Francisco de Anaia (2 caravels) |

| 2.Mozambique (Moçambique) | sheikh Zacoeja? | (factory est. 1502) | N/A | Gonçalo Baixo | N/A |

| 3. Kilwa (Quíloa) | sultan Muhammad Arcone | Fort Gereza (est. 1505) | Pêro Ferreira Fogaça (550 men) | Fernão Cotrim | Gonçalo Vaz de Goes (1 caravel) |

| 4. Malindi (Melinde) | Bauri sheikh | (factory est. 1500?) | N/A | João Machado | N/A |

| 5. Anjediva (Angediva) | N/A | Fort São Miguel (est. 1505) | Manuel Paçanha (80 men) | Duarte Pereira | João Serrão (1 galley, 2 brigantines) |

| 6. Cannanore (Canonor) | Kolathiri Raja | Fort Sant' Angelo (factory 1502, fort 1505) | D. Lourenço de Brito (150 men) | Lopo Cabreira | Rodrigo Rabello & Fernão Bermudez. (2 navetas) |

| 7. Cochin (Cochim) | Trimumpara Raja | Fort Manuel (factory 1500, fort 1503) | D. Álvaro de Noronha (? men) | Lourenço Moreno | Lourenço de Almeida (?) |

| 8. Quilon ((Coulão) | Regents for Govardhana Martanda | N/A | N/A | ||

See also

Notes

- ↑ The letter of the Mameluke sultan to the Pope is transcribed in Damião de Góis's Chronica, pp. 124–125. King Manuel I's reply to the pope, dated June 1505, is also transcribed. See also Barrros (Dec. I, Lib. 8, c. 2)

- ↑ Subrahmanyam (1997: p. 55)

- ↑ Subrahmanyam (1997: p. 55)

- ↑ Logan (1887: p. 312)

- ↑ Cunha (1875: p. 301)

- ↑ Cameron (1973: p.19)

- ↑ Barros Dec. I, Bk. VIII, c.3 p.195 Barros does not give ship names in the list (although he will refer to a few by name after). He says there were 22 ships and names 20 captains – Barros forgets Felipe Rodrigues and omits the name of Pêro de Anaia from the main list (but goes on to note that 'Pero da Nhaya' led a squadron of 6 ships to Sofala). He refers to Ruy Freire de Andrade merely as 'Ruy Freire', to Fernão Bermudez as 'Bermum Dias, fidalgo castelhano', to Francisco de Sá as 'Fernando Deça de Campo Maior' and to Lucas da Fonseca as 'd'Affonseca'. Among the other name variations, Barros uses 'Lopo de Deos' and refers to Gonçalo Vaz de Goes as 'de Boes'.

- ↑ See also Ferguson (1907: p.290-91)

- ↑ Lach (1965: p.108-09)

- ↑ Godinho (1963, vol. 3, p.58); Lach (1965: p.108-09)

- ↑ Lach (1965: p.109-10)

- ↑ This summary of the regimento is drawn principally from Damião de Góis (v.2, p.150-51)

- ↑ Castello Branco (2006: p.60)

- ↑ Ferguson (1907: p.288)

- ↑ In Barros (p.195) list of 22 ships and 20 captains, Anaia is one of the names conspicuously omitted. Barros does not mention the foundering, but merely notes that Anaia left later with his Sofala squad.

- ↑ Quintella, p.285

- ↑ Barros, p.195

- ↑ Barros p.196 does not mention Pacanha, and says only that the second squadron was placed under Sebastião de Sousa, captain of the Concepção

- ↑ Barros, p.197

- ↑ Damião de Góis (p.157)

- ↑ Chroniclers, e.g. Góis, p.157, report the name of the Kenyan bay to be 'St. Helena'.

- ↑ A nobleman first time at sea, João Homem famously ordered garlic and onions to be hung from the sides of his ship, to help himself (and the crew) differentiate starboard from port side. Homem's orders were barked 'to garlic' or 'to onions', much as red and green lights are used today.

- ↑ Theal (1907: p.248ff).

- ↑ The original name is worth noticing, given that Almeida had abandoned his old Order of Santiago that very January. But it was probably named because July 25, the day of Kilwa's capture, is also the Feast of St. James, as noted by Barros.

- ↑ Theal (1907: 247)

- ↑ Theal (1907: p.248)

- ↑ Chroniclers are eager to point out that Almeida also released 800 others he had captured, hailing it as a testament to Almeida's magnanimity, and contrast it to the cruel treatment usually meted out by other captains, esp. Gama and Albuquerque. (Theal, 1907: p.251).

- ↑ alt. 'Cincatora' or 'Cintacola', is described by Duarte Barbosa (p.78) as a port and fortresss at the mouth of the 'Agali' river (prob. Kali River, just a little north of Anjediva). As a result, Cincatora has been usually identified on the location of modern Sadashivgad. However, Cunha (1875:p.304) place it further south, at Ankola. This agrees with Varthema (p.120), who claims Cintacora was a subject of Batecala

- ↑ At least according to Ludovico di Varthema (p.121-22)

- ↑ Barros (v.2, p.344-45)

- ↑ Barros (v.2, p.344-45)

- ↑ Logan (1887: 312-3)

- ↑ Barros, p.350

- ↑ Castanheda, v.2, p.70

- ↑ Barros (v.2, p.351ff.) refers to the heir as 'Nambeadora'. But during the Battle of Cochin (1504), the heir is referred to as 'Candagora'. In his coronation comments, Barros notes that there is indeed another unnamed but more legitimate heir the Trimumpara Raja of Cochin, but that he fought for the Zamorin and was disinherited (might that be Elcanol of Edapalli?)

- ↑ Barros, vol. 2, p.366

- ↑ Barros (vol. 2, p. 360) asserts September; Ferguson (1907: p. 302) cites November 19, 1505 as the departure date.

- ↑ Exact return dates vary in the chronicles, e.g. Castanheda says November 26, etc. Here we are following the details as sorted by Ferguson (1907:295)

- ↑ Barros (v.2, p.359). The west coast of Madagascar was first sighted by Diogo Dias back in 1500; one (unreliable) chronicler (Gaspar Correia (p.418)) asserts that the outer route might have already been sailed on the outward journey of Diogo Fernandes Pereira in 1503; but Fernão Soares's sighting of the east coast is the first to get wider confirmation.

Sources

- Duarte Barbosa (c. 1518) O Livro de Duarte Barbosa [Trans. by M.L. Dames, 1918–21, An Account Of The Countries Bordering On The Indian Ocean And Their Inhabitants, 2 vols., 2005 reprint, New Delhi: Asian Education Services.]

- João de Barros (1552–59) Décadas da Ásia: Dos feitos, que os Portuguezes fizeram no descubrimento, e conquista, dos mares, e terras do Oriente.. [Dec. I, Lib 7.]

- Fernão Lopes de Castanheda (1551–1560) História do descobrimento & conquista da Índia pelos portugueses [1833 edition]

- Gaspar Correia (c. 1550s) Lendas da Índia, first pub. 1858–64, in Lisbon: Academia Real das Sciencias.

- Damião de Góis (1566–67) Crónica do Felicíssimo Rei D. Manuel

- Jerónimo Osório (1586) De rebus Emmanuelis [trans. 1752 by J. Gibbs as The History of the Portuguese during the Reign of Emmanuel London: Millar]

- Ludovico di Varthema (1510) Itinerario de Ludouico de Varthema Bolognese (1863 translation by J.W. Jones,The Travels of Ludovico di Varthema, in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508, London: Hakluyt Society. online)

Secondary:

- Campos, J.M. (1947) D. Francisco de Almeida, 1° vice-rei da Índia, Lisbon: Editorial da Marinha.

- Castello-Branco, T.M.S. de (2006) Na Rota da Pimenta. Lisbon: Presença.

- Cunha, J.G. da (1875) "An Historical and Archaeological Sketch of the Island of Angediva", Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Volume 11, p. 288-310 online

- Danvers, F.C. (1894) The Portuguese in India, being a history of the rise and decline of their eastern empire. 2 vols, London: Allen.

- Ferguson, D. (1907) "The Discovery of Ceylon by the Portuguese in 1506", Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 19, No. 59 p. 284-400 offprint

- Godinho, Vitorino Magalhães (1963) Os Descobrimentos e a economia mundial. Second (1984) edition, four volumes. Lisbon: Editorial Presença.

- Lach, Donald F. (1963) Asia in the Making of Europe: Vol. 1 – the century of discovery. 1994 edition, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Logan, W. (1887) Malabar Manual, 2004 reprint, New Delhi: Asian Education Services.

- Mathew, K.S. (1997) "Indian Naval Encounters with the Portuguese: Strengths and weaknesses", in Kurup, editor, India's Naval Traditions. New Delhi: Northern Book Centre.

- Newitt, M.D. (1995) A History of Mozambique. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Quintella, Ignaco da Costa (1839–40) Annaes da Marinha Portugueza, 2 vols, Lisbon: Academia Real das Sciencias.

- Subrahmanyam, S. (1997) The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Theal, G.M. (1898) Records of South-eastern Africa collected in various libraries & archive departments in Europe – Volume 2, London: Clowes for Gov of Cape Colony. [Engl. transl. of parts of Gaspar Correia]

- Theal, G.. M. (1902) The Beginning of South African History. London: Unwin.

- Theal, G.M. (1907) History and Ethnography of Africa South of the Zambesi – Vol. I, The Portuguese in South Africa from 1505 to 1700 London: Sonneschein.

- Whiteway, R. S. (1899) The Rise of Portuguese Power in India, 1497-1550. Westminster: Constable.

_-_Autor_desconhecido.png.webp)