Azerbaijani: Şəmkir minarəsi | |

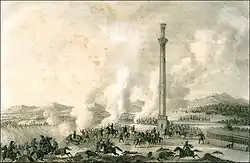

The tower by Frédéric Dubois de Montpéreux | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Material | brick |

| Height | 61 metres (200 ft) |

| Completion date | 11th century |

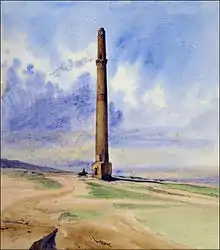

The Shamkir minaret,[1] or the Shamkir tower, also known as the “Shamkhor pillar”,[2] is a tower or minaret located near Shamkir (now a city in Azerbaijan). The view of the tower built at the end of the 11th century[3][4] is known from the detailed written description of N. Florovsky,[5] who visited the medieval settlement of Shamkir in the first half of the 19th century, as well as from the paintings of such artists as Grigory Gagarin and Dubois de Montpereux.[6]

Tower details

The monument attracted the attention of many travelers and was repeatedly mentioned and even described.[2] The earliest reference of the monument is found in Abulfeda (the beginning of the 14th century), noting that the minaret is very high and outstanding. Referring to thestylistic features of its architecture, Mikael Useynov and Leonid Brittanytsky dated the minaret since the 12th to the beginning of the 13th century.[2][7] G. Gamba, in the description of his travel across the Caucasus, compared the tower with Trajans Column in Rome and noted that the mullahs used the tower to call Muslims to prayer.[8] Eduard Eichwald saw the minaret in 1826, but when Boris Dorn visited the area of the Shamkir settlement in 1861 found only its ruins and reported about its destruction to the ground.[2] The minaret is known for the complementary drawings of Dubois de Montpereux[6] and Grigory Gagarin. However, these drawings do not give the idea of its past surroundings. Therefore, the account of Arseny Sukhanov, who passed through Shamkir in the 1650s, is especially interesting.[2] He wrote that he "passed through the empty city, it was great, made of brick and a stone from the soil, but inside there was another; both with damaged walls, but only the high minaret made of brick was intact; there was a brick bridge across the river; a great river, divided into five rivers; along the river bank; having crossed that river, on the shore we spent the night against the empty hail of that”.[9]

The tower was mentioned by the American Protestant missionary Eli Smith:[10]

The east wind, even after the fog of the morning had subsided, had seemed all day surcharged with noxious vapours; and before reaching the Shamkhor column, I felt the signs of the approaching fever. We stopped a moment to examine that antiquities. It is built of brick, has spiral stairs within to its top, and is said to be 180 feet in height. On a stone at the base there is an inscription in Arabic script, while another encircles in the upper part, where there is also a surrounded gallery with a door that opens from within. Its origin is unknown, but, apparently, it was built as a mosque’s minaret. The other ruins of the place are the foundations of a large caravanserai, and several small Muslim tombs.[11]

The representation of the monument given by N. Frolovskys is detailed described in his "Review of the Russian Possessions in the Caucasus published in 1836, considering that “the most noteworthy of all the monuments there (meaning the Elisavetpol area) is the Shamkhor Pillar, built among the plains on the left bank of the Shamkhor river, 25 versts from the city, and open to the gaze of almost 30 versts. It is surrounded by the ruins of a fortress and other buildings, which were led round by a square wall that stretched a hundred fathoms from north to south, and sixty fathoms across. The time of the pillars construction is unknown, however, an unaccountable story attributes it to Alexander the Great. The base of the column represents a cubic figure and has seven arshins in diameter and six and a quarter in height; on this basis, another pedestal of the same figure is arranged containing six arshins in width, five arshins in height. A round column rises on it, which has a diameter at the base of five, and at the top up to four arshins, eighteen fathoms in height, with a base of up to twenty-two fathoms. The upper part of it is surrounded by a quadrangular cornice, each side enclose 5 yards; under the cornice there is an inscription, believed to be in the Kufic language. Above this cornice, there is still a round column, six fathoms high, which has already collapsed at the top; its diameter at the base is not more than one fathom. The entire pillar has a height of up to 28 yards. In the middle of the column there is a spiral staircase consisting of 124, large and almost destroyed, steps, which are very difficult to climb. In the upper part, under the cornice, there was also a staircase, judging by the indentations in the wall, into which the steps were probably fortified. The pillar is built of bricks on dry matter mixed with sand and small stones; the work is extremely durable and beautiful; the cement is so strong that it has completely merged with the brick. It is impossible without regret to see that time is already beginning, in many places, to destroy this beautiful monument of antiquity, and even the inclination of the pillar is quite noticeable [“It is doubtful that this column served as an observatory, as Gamba believes (Voyages dans la Russie meridionale etc.), and very likely that it was nothing more than a minaret, from the top of which Muslims were called to prayer“]”[2][5][7]

Architecture

The minarets design is common. The base is a prismatic volume with an inlet opening. The wedge-shaped bevels create a transition to an octahedral space, on which the slightly thinning tower of the minaret rises. The interpretation of the balcony for the muezzin is interesting. Gagarins drawing captures large articulations of the supporting stalactite cornice, under which there is an inscription ribbon. Above the balcony there is of an elongated proportions a small lancet opening.[7]

The top of the minaret represents the starting material for the restoration of approximately same time minarets in Karabaglar and Nakhichevan.[2] The minaret is completed with a kind of "lantern" with a light end-to-end arcade. The combination of the "lantern" with a developed balcony is somewhat unusual[7] for a muezzin and therefore rare.[2] Such a "flashlight" is common in the minarets of the neighbouring countries. It is not found in the minarets of Shirvan, and for the muezzin it was intended a balcony with a circular detour. The figure also shows the difference in the patterns of the brickwork of the tower up to its top. In addition, a wide decorative strip stands out on the tower cut by slit-like openings, approximately at the height of its upper third.[2]

Kufic tower inscription

In 1970, when laying a gas pipeline in the Shamkir region, the Azerbaijan SSR, a Kufic inscription was discovered on the site of the Shamkir town. It is shedding light on its purpose and date of construction.[12] The Arabic-language inscription on this stone slab, which is nowadays in the Museum of History of Azerbaijan, says that the tower was built at the expense of the Sheikh al-Saleh ibn Afshin in 493 AH (1099/1100).

Bismillah, with the help of Almighty Allah, at his request, under his protective means of Sheikh al-Saleh ibn Afshin, was ordered to build this watchtower in the series of defensive structures in the year four hundred ninety-three.

The Azerbaijani historian Meshadikhanum Neymat examined the text of the inscription and came to the conclusion that the Shamkir minaret was one of those structures that were designated for coverage, that is, the defence of the city. It served as a watchtower. Neymat noted that the inscription also shows that the minaret was built not in the 12-13th centuries, as the researchers of the monument's history construction assumed, but at the end of the 11th century.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ "Şəmkir qulləsi" (in Azerbaijani). shamkir-archeo.com. Archived from the original on July 13, 2021. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Бретаницкий, Леонид (1966). Зодчество Азербайджана XII-XV вв. и его место в архитектуре Переднего Востока. Moscow: Наука. pp. 90–92.

- ↑ Valikhanli, Naila (2016). Azərbaycan VII-XII əsrlərdə: tarix, mənbələr, şərhlər / Azerbaijan in VII-XII centuries: history, sources, comments (PDF). Baku: Azərbaycan Milli Elmlər Akademiyası Milli Azərbaycan Tarixi Muzeyi. p. 163.

- ↑ "Şəmkir qülləsinin kitabəsi" (in Azerbaijani). azhistorymuseum.az. Archived from the original on June 16, 2013. Retrieved July 13, 2021.

- 1 2 Florovsky, N. (1836). Елисаветпольский край // Обозрение российских владений за Кавказом. Елисаветпольский округ. Saint Petersburg: Типография департамента внешней торговли. pp. 363–364.

- 1 2 Montperreux, Dubois de (1840). Voyage Autour Du Caucase, Chez Les Tcherkesses Et Les Abkhases, En Colchide, En Géorgie, En Arménie Et En Crimée. Vol. 4. Paris: Librairie De Gide. p. 147.

- 1 2 3 4 Useynov, Mikayil (1963). История архитектуры Азербайджана / History of architecture of Azerbaijan. Baku: Гос. издат. литературы по строительству, архитектуре и строительным материалам. pp. 74–75.

- ↑ Jean François, Gamba (1826). Voyages dans la Russie meridionale. Vol. II. Paris. pp. 245–246. Archived from the original on 2021-07-13.

- ↑ Арсения Суханова, Проскинитарий (1889). Православно-палестинский сборник, 1889. Vol. VII. Saint Petersburg: Православно-палестинский сборник. p. 103.

- ↑ Ritter, Carl (1843). Die Erdkunde Asien, Kleinasien, Arabien. Berlin. p. 765.

- ↑ Eli Smith; H G O Dwight; Josiah Conder (1834). Missionary researches in Armenia: including a journey through Asia Minor, and into Georgia and Persia, with a visit to the Nestorian and Chaldean Christians of Oormiah and Salmas. London: George Wightmann. p. 171.

- 1 2 Meshadihanum Nejmat (1991). Корпус эпиграфических памятников Азербайджана / Corpus of epigraphic monuments of Azerbaijan (PDF). Baku. ISBN 5-8066-0322-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-11-15.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)