Shawinigan | |

|---|---|

| Ville de Shawinigan | |

Aerial view of Saint-Maurice River and the city | |

Coat of arms Logo | |

| Nickname: The City of Electricity | |

| Motto: Age Quod Agis (Do what you are doing) | |

Shawinigan Location in Quebec  Shawinigan Location in Canada. | |

| Coordinates: 46°34′N 72°45′W / 46.567°N 72.750°W[1] | |

| Country | Canada |

| Province | Quebec |

| Region | Mauricie |

| RCM | None |

| Settled | 1851 |

| Constituted | January 1, 2002 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Michel Angers |

| • Federal riding | Saint-Maurice—Champlain |

| • Prov. riding | Laviolette and Saint-Maurice |

| Area | |

| • City | 798.80 km2 (308.42 sq mi) |

| • Land | 729.98 km2 (281.85 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 31.77 km2 (12.27 sq mi) |

| Population (2021)[3] | |

| • City | 49,620 |

| • Density | 68/km2 (180/sq mi) |

| • Urban density | 1,225.4/km2 (3,174/sq mi) |

| • Pop 2016-2021 | |

| • Dwellings | 27,444 |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Postal code(s) | |

| Area code | 819 |

| Highways | |

| Website | www |

Shawinigan (/ʃəˈwɪnɪɡən/) is a city located on the Saint-Maurice River in the Mauricie area in Quebec, Canada. It had a population of 49,620 as of the 2021 Canadian census.

Shawinigan is also a territory equivalent to a regional county municipality (TE) and census division (CD) of Quebec, coextensive with the city of Shawinigan. Its geographical code is 36. Shawinigan is the seat of the judicial district of Saint-Maurice.[5]

The name Shawinigan has had numerous spellings over time: Chaouinigane, Oshaouinigane, Assaouinigane, Achawénégan, Chawinigame, Shawenigane, Chaouénigane. It may mean "south portage", "portage of beeches", "angular portage", or "summit" or "crest".[1] Before 1958, the city was known as Shawinigan Falls.

Shawinigan is the birthplace of former Prime Minister of Canada Jean Chrétien.

History

.svg.png.webp)

In 1651, the Jesuit priest Buteaux was the first European known to have travelled up the Saint-Maurice River to this river's first set of great falls. Afterwards, missionaries going to the Upper Saint-Maurice would rest here.[1] Before Shawinigan Falls was established, the local economy had been largely based on lumber and agriculture.

Boomtown

In the late 1890s, Shawinigan Falls drew the interest of foreign entrepreneurs such as John Joyce and John Edward Aldred of the Shawinigan Water & Power Company (SW&P), and of Hubert Biermans of the Belgo Canadian Pulp & Paper Company because of its particular geographic situation. Its falls had the potential to become a favorable location for the production of hydroelectricity.[7]

In 1899, the SW&P commissioned Montreal engineering firm Pringle and Son to design a grid plan for a new industrial town on the banks of the Saint-Maurice River, providing the ground work for what would become Downtown Shawinigan.[8]

In 1901, the place was incorporated as the Village Municipality of Shawinigan Falls and gained town (ville) status a year later in 1902. The hydro-electric generating station contributed to rapid economic growth and the town achieved several firsts in Canadian history: first production of aluminum (1901), carborundum (1908), cellophane pellets (1932).[1][9] Shawinigan Falls also became one of the first Canadian cities with electric street lighting.

Urban Growth

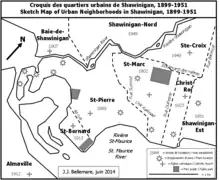

For decades, the local pulp and paper, chemical and textile industries created thousands of jobs and stimulated city growth (see Sketch Map of Urban Neighborhoods in Shawinigan, 1899-1951).

Urban development steadily increased in Downtown Shawinigan Falls. By 1921, this sector was densely filled with commercial buildings on Fourth and Fifth street, as well as Station Avenue, one-family residences along the Riverside corridor (current-day St-Maurice Drive) and multi-story tenements elsewhere.[10]

The Olmsted Brothers design firm was hired by the city to implement a beautification program. By the late 1920s, Downtown Shawinigan Falls was home to a public market, a fire station, a technical school, several church buildings and two landscaped public parks, including the Saint-Maurice Park.[11]

Many of the opulent uphill homes located in the somewhat secluded areas of Maple Street and Hemlock Avenue were occupied by more affluent people, many of whom happened to belong to the once vibrant English-speaking community, which at times comprised more than 30% of the local population.

As industrial plants began operation eastward and northward, neighbourhoods were established in Uptown Shawinigan Falls. The emergence of these new districts was defined by and intertwined with the parish structure of the Roman Catholic Church. The Saint-Marc neighbourhood, originally known as Village St-Onge, was annexed in 1902, extending the city limits to Dufresne Street. The uptown presence of the Canadian Carborundum and Alcan no. Two plants favoured the foundation the Christ-Roi neighbourhood, which was annexed in 1925 extending the city limits to St Sacrement Boulevard. The land now occupied by the section of town currently known as Shawinigan-Est was annexed in 1932.

Uptown Shawinigan Falls had its own fire station by 1922 and its own landscaped public park and swimming pool by 1940.[12]

Westside near the Shawinigan River, the existence of the pulp and paper Belgo plant attracted enough residents to form a small, yet stable independent urban community called Baie-de-Shawinigan.

Across the Saint-Maurice River, Shawinigan-Sud (then Almaville) maintained home-rule and developed as a residential hub.

Great Depression

Local prosperity was interrupted by the Great Depression in the 1930s. Many plants were forced to temporarily reduce or stop their production, which left many residents jobless. Many families needed public assistance to survive. The City Council enacted a public works program to help families.

The promenade along the Saint-Maurice River was a project to create work during the depression.

World War II

World War II put Shawinigan Falls, and many others cities in Canada, back on the path of economic recovery.

During hostilities, the windows of local power plants were painted black to prevent any possible German aerial attack.

The Shawinigan-based 81st Artillery Battery was called to active duty during World War II. Its members were trained in Ontario and the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1944 and contributed to the Allies' effort in the Normandy Landings in 1944-45, which led to the Liberation of France.[13]

In 1948, a cenotaph, known as Monument des Braves, was erected in downtown Shawinigan Falls at the intersection of Fourth Street and Promenade du Saint-Maurice (then Riverside Street) near the Saint-Maurice River, in honour of soldiers who died during that conflict as well as World War I.

Rise of the working class

By the early 1950s, the industrial growth in Shawinigan Falls was such that the city offered the steadiest employment and the highest wages in Quebec.[14] Due to this advantageous position, Shawinigan Falls became a hot bed for organized labor and bargaining power. The rise of its working class also favoured the presence of numerous independently owned taverns.

Labour unions

As its working class gained economic ground and political leverage, Shawinigan Falls became fertile ground for labour unions. The workers of the Belgo pulp and paper plant went on strike in 1955. In the 1952 provincial election, Shawinigan sent a Liberal member to the legislature. The gesture was largely considered an affront to Premier Maurice Duplessis, who responded by refusing to approve the construction of a new bridge between Shawinigan Falls and Shawinigan-Sud. The new bridge was not built until after the Liberal Party won the 1960 election. It was completed on September 2, 1962.[15]

Taverns

In the 1950s, a number of taverns provided a male-only social environment for industrial workers. They were mostly concentrated in Downtown Shawinigan Falls (Saint-Bernard and Saint-Pierre), as well as in the Saint-Marc neighbourhood, as Shawinigan-Sud remained a dry town until 1961,[16] and included the following venues:

| Name | Also Known As | Address | Neighbourhood | Current Status |

| Au Pied du Courant | 1885, avenue Saint-Marc | Saint-Marc | demolished | |

| Chez Bob | Chez Maxime | 413, avenue Mercier | Saint-Pierre | out of business |

| Chez Camille | Chez Armand, Taverne Station | 902, avenue de la Station | Saint-Pierre | demolished |

| Chez François | Taverne Bellevue, Cabaret La Vie est Belle | 2991, boulevard des Hêtres | Sainte-Croix | still in business |

| Chez Georges | Bar Le Transit | 2172, avenue Cloutier | Saint-Marc | out of business |

| Chez Jos | 482, 5e rue | Saint-Pierre | demolished | |

| Chez Léo | 820, 4e rue | Saint-Pierre | out of business | |

| Chez Maurice | Jos Bar Terrasse | 666, 5e rue | Saint-Pierre | still in business |

| Chez Paul (Bistro Bar) | 303, avenue Tamarac | Saint-Bernard | out of business | |

| Chez Paul (Taverne) | Au Gobelet | 403, avenue Tamarac | Saint-Pierre | burned down |

| Chez Rosaire | 763, rue Lambert | Saint-Marc | still in business | |

| Corvette | 822, rue Trudel | Saint-Marc | burned down in 1973 | |

| Taverne Laliberté | Taverne des Expos, Bar de l’Énergie | 1572, avenue Saint-Marc | Saint-Marc | still in business |

| Taverne Moderne | 2282, avenue Saint-Marc | Saint-Marc | still in business | |

| Taverne des Sports | Club Social | 382, 5e rue | Saint-Pierre | demolished |

In 1951, the local tavern keepers formed a business association.[17]

In 1981, the provincial government enacted a law that gave women access to most taverns. By 1986, women had already been admitted in most taverns.[18]

While a handful of local taverns evolved into bistros or restaurants, most of them did not survive the industrial decline that characterized the last third of the 20th Century.

Decline

In the 1950s, Shawinigan Falls entered a period of decline that would last for several decades. Technological improvements made industries less dependent on Shawinigan Falls' geographic location. Therefore, many employers would relocate to nearby larger cities or close down.

In 1958, it received city (cité) status, and its name was abbreviated to just Shawinigan.[1]

As a reaction to declining opportunities, many residents, many of whom were English-speakers, left the area. Shawinigan High School is the only remaining English-language school in the city following the closure of St. Patrick's (closed circa 1983). Shawinigan's last English-language newspaper, the Shawinigan Standard, ceased publication at the end of 1970.[19]

In 1963, the provincial government of Jean Lesage nationalized eleven privately owned electricity companies, including SW&P. While benefiting the population in general, the decision may have been damaging to local interests.

Emerging hospitality industry

Traditionally, Shawinigan has been home to a number of hotels and inns, including the following:

| Name | Also Known As | Address | Neighbourhood | Year Completed | Current Status |

| Cascade Inn | 695, 7e rue | Saint-Pierre | 1901 | burned down in 1986 | |

| Château de la Mauricie | Hôtel La Mauricie | 822, rue Trudel | Saint-Marc | burned down in 1973 | |

| Château Turcotte | 1000, avenue Melville | Saint-Pierre | 1858 | burned down in 1878 | |

| De Lasalle | Hôtel Central, Grand Central |

590, 3e rue | Saint-Paul, Grand-Mère | damaged by fire in 2012, out of business[20] | |

| Des Chutes | Riverside | 856, 4e rue | Saint-Pierre | burned down in 1992 | |

| Dufresne | 702, 4e rue | Saint-Pierre | 1905 | in business until 1914, later demolished | |

| Escapade | 3383, rue Garnier | Saint-Charles-Garnier | 1977 | out of business - 2017 | |

| Gouverneur | 100, promenade du Saint-Maurice | Saint-Pierre | 1998 | still in business | |

| Grand-Mère Inn | Laurentide Inn | 10, 6e avenue | Saint-Paul, Grand-Mère | 1897 | burned down in 2004, demolished in 2010[21] |

| La Rocaille | 1851, 5e avenue | Saint-Jean-Baptiste, Grand-Mère | still in business | ||

| Laviolette | 1608, avenue Saint-Marc | Saint-Marc | demolished | ||

| Royal | 693, 4e rue | Saint-Bernard | 1901 | demolished | |

| Shawinigan Hotel[22] | Hôtel Racine | 602, 5e rue | Saint-Pierre | 1903 | burned down in 1990 |

| Vendôme | New Vendôme | 943, avenue Cascade | Saint-Pierre | circa 1908 | burned down in 1958[23] |

| Windsor | 1787, avenue Champlain | Saint-Marc | 1905 | in business until the 1930s, later demolished |

In order to offset the decline of the heavy industry, leaders have promoted the expansion of the local hospitality industry. The most notable example of that initiative is the establishment of La Cité de l'Énergie, a theme park based on local industrial history, with a 115-metre-high (377 ft) observation tower. Since it opened in 1997, it has attracted thousands of visitors to the area. It currently hosts bus tours and cruises, as well as entertainment shows and interactive exhibits. Since 2012, it is also home to the Museum of Prime Minister Jean Chrétien, a venue similar to those operated by the U.S. presidential library system and which focuses on the gifts received by the former Prime Minister of Canada (1993-2003) during his official duties.[24]

Mergers

In 1998, Shawinigan merged with the Village Municipality of Baie-de-Shawinigan.[1]

On January 1, 2002, Shawinigan amalgamated with much of the Regional County Municipality of Le Centre-de-la-Mauricie. The following municipalities were part of the merger:

| Municipality | Year of Foundation [25] | Population (1996) [26] |

| Shawinigan [27] | 1901 | 18,678 |

| Grand-Mère[28] | 1898 | 14,223 |

| Shawinigan-Sud | 1912 | 11,804 |

| Saint-Georges-de-Champlain | 1915 | 3,929 |

| Lac-à-la-Tortue | 1895 | 3,169 |

| Saint-Gérard-des-Laurentides | 1924 [29] | 2,155 |

| Saint-Jean-des-Piles | 1897 | 693 |

Geography

Climate

Shawinigan has a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfb) featuring cold and snowy winters coupled with warm and humid summers. Precipitation is moderate to high year round, resulting in heavy winter snowfall, typical of Eastern Canada.

| Climate data for Shawinigan | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 10.5 (50.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

17.8 (64.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

33.9 (93.0) |

35.6 (96.1) |

36.7 (98.1) |

37.2 (99.0) |

32.8 (91.0) |

30.0 (86.0) |

19.4 (66.9) |

11.1 (52.0) |

37.2 (99.0) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −8.0 (17.6) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

1.1 (34.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

18.1 (64.6) |

22.8 (73.0) |

25.1 (77.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

17.8 (64.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

3.1 (37.6) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −13.2 (8.2) |

−10.6 (12.9) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

4.2 (39.6) |

12.0 (53.6) |

17.1 (62.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

18.3 (64.9) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.8 (44.2) |

−0.4 (31.3) |

−8.7 (16.3) |

4.5 (40.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −18.3 (−0.9) |

−16.0 (3.2) |

−9.2 (15.4) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

5.8 (42.4) |

11.3 (52.3) |

14.1 (57.4) |

13.0 (55.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−4.0 (24.8) |

−13.1 (8.4) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −47.0 (−52.6) |

−37.8 (−36.0) |

−33.9 (−29.0) |

−24.4 (−11.9) |

−7.2 (19.0) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−6.7 (19.9) |

−11.1 (12.0) |

−25.0 (−13.0) |

−42.2 (−44.0) |

−47.0 (−52.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 78.9 (3.11) |

60.1 (2.37) |

73.5 (2.89) |

81.1 (3.19) |

97.6 (3.84) |

101.6 (4.00) |

107.6 (4.24) |

103.0 (4.06) |

99.3 (3.91) |

92.5 (3.64) |

82.5 (3.25) |

91.0 (3.58) |

1,068.6 (42.07) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 17.7 (0.70) |

15.0 (0.59) |

34.5 (1.36) |

67.7 (2.67) |

97.1 (3.82) |

101.6 (4.00) |

107.6 (4.24) |

103.0 (4.06) |

99.3 (3.91) |

91.9 (3.62) |

58.5 (2.30) |

25.6 (1.01) |

819.4 (32.26) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 61.1 (24.1) |

45.2 (17.8) |

39.0 (15.4) |

13.4 (5.3) |

0.5 (0.2) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.6 (0.2) |

24.0 (9.4) |

65.4 (25.7) |

249.1 (98.1) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 12.4 | 9.1 | 10.0 | 11.2 | 12.5 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 11.9 | 11.1 | 13.1 | 143.4 |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 1.5 | 1.1 | 4.0 | 9.6 | 12.5 | 13.3 | 13.3 | 13.0 | 12.6 | 11.7 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 101.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.2 cm) | 11.4 | 8.0 | 6.0 | 2.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | 4.7 | 10.7 | 43.5 |

| Source: Environment Canada[30] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

In the 2021 Census of Population conducted by Statistics Canada, Shawinigan had a population of 49,620 living in 25,060 of its 27,444 total private dwellings, a change of 0.5% from its 2016 population of 49,349. With a land area of 729.98 km2 (281.85 sq mi), it had a population density of 68.0/km2 (176.1/sq mi) in 2021.[31]

Economy

- an Alcan aluminum plant: built in 1941 and located at 1100 Boulevard Saint-Sacrement, it took over the production of a 1901 structure which is located near the Saint-Maurice River and is currently managed by La Cité de l'Énergie. It has since shut down in 2015;[32]

- the Belgo pulp and paper plant: AbitibiBowater Inc. ceased its production on February 29, 2008;[33]

- The Laurentide Paper Company: AbitibiBowater Inc. the last major paper mill still active in Shawinigan, located in the Grand-Mère district.

- large hydroelectric complex at Shawinigan Falls: the Shawinigan 2 (1911) and Shawinigan 3 (1948) power plants, established by the Shawinigan Water & Power Company, they have been the property of Hydro-Québec since 1963 and are also located near the Saint-Maurice River.

Arts and culture

- The Classique internationale de canots de la Mauricie: a prestigious marathon canoe race, held annually since 1934.

- Grand-Mère's Fête nationale du Québec celebration: consisting of a bonfire and a live performance from local musicians, its audience arguably ranks among the largest crowds in the Mauricie area. It takes place at the Parc de la rivière Grand-Mère.[34] The tradition goes back decades ago.[35]

Attractions

- The Trou du Diable (Devil's Hole): this mysterious location consists of a swirl in the Saint-Maurice River nearby the falls. Legend has it, the Trou du Diable has no bottom, making it impossible to rescue anyone who falls into it [36]

- Parc Saint-Maurice: located in downtown Shawinigan, it was part of the city's original plan.

- the 62nd (Shawinigan) Field Artillery Regiment: a Reserve unit of the Canadian Army which was called to active duty during World War II

- La Cité de l'Énergie

- the Shawinigan Cataractes: the only QMJHL franchise to have stayed in the same city since the league's inception in 1969. They play at the Centre Gervais-Auto

- the Shawinigan-Sud Tax Centre

Sports

The Shawinigan Cataractes of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League play out of the Centre Gervais Auto in Shawinigan. It played host to the 2012 Memorial Cup hockey tournament and won the Championship, defeating the London Knights in the final.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Many of the oldest streets of Shawinigan were numbered, like the streets of Manhattan, New York. Similarly, Avenue Broadway was named after the famous Manhattan thoroughfare.

Several other streets and avenues were named to honour famous people, including:

Religion

In recent years, the church attendance of Catholics in Shawinigan has been on the decline. As a result, the Roman Catholic Diocese of Trois-Rivières has had difficulties maintaining its churches and merged a number of its parishes. The Catholic churches are:

| Church | Location | Year of foundation | Status |

| Saint-Pierre (Saint Peter) | 792, avenue Hemlock | 1901 | active |

| Saint-Marc (Saint Mark) | 1895, avenue Champlain | 1911 | active |

| Sacré-Cœur (Sacred Heart) | 17, rue de l'Église, Baie-de-Shawinigan |

1911 | active |

| Saint-Bernard (Saint Bernard) | 562, 3e Rue | 1912 | inactive closed in 2005 [37] |

| Christ-Roi (Christ the King) | 1250, rue Notre-Dame | 1938 | inactive closed in 1994 demolished in 2002 [38] |

| Sainte-Croix (Holy Cross) | 2153, rue Gignac | 1949 | inactive closed in 2004 [39] |

| Saint-Charles-Garnier (Saint Charles Garnier) | 2173, avenue De la Madone | 1949 | active |

| Immaculate Heart of Mary Mission (English-speaking community) |

773, avenue de la Station | 1949 | inactive closed in 1990 |

| L’Assomption (Assumption) | 4393, boulevard Des Hêtres | 1951 | active |

| Desserte Sainte Hélène (Saint Helena Mission) | 2350, 93e Rue | 1967 | inactive closed |

The current church building for Saint-Pierre was constructed between 1908 and 1937. The structure's stained glass was designed by Italian Canadian artist Guido Nincheri between 1930 and 1961.

Education

There are eight public schools.[40] Seven of them are under the supervision of the Commission scolaire de l'Énergie school board.

| School | Level | Location | Number of students |

| Carrefour Formation Mauricie | Vocational education | 5105, avenue Albert-Tessier | 808 |

| Centre d'éducation des adultes du Saint-Maurice | Adult education | 1092, rue Trudel | 1,353 |

| École secondaire des Chutes | Secondary | 5285, avenue Albert-Tessier | 714 |

| Immaculée-Conception (Immaculate Conception) | Elementary | 153, 8e Rue | 220 |

| Saint-Charles-Garnier (Saint Charles Garnier) | Elementary | 2265, rue Laflèche | 157 |

| Saint-Jacques (Saint James) | Elementary | 2015, rue Saint-Jacques | 220 |

| Saint-Joseph (Saint Joseph) | Elementary | 1452, rue Châteauguay | 155 |

Children who meet Charter of the French Language requirements for instruction in English can attend Shawinigan High School. Its campus is located at 1125, rue des Cèdres and is operated by the Central Québec School Board.

Shawinigan is also home of the Séminaire Sainte-Marie, a private institution that provides the secondary curriculum and of the Collège Shawinigan: a CEGEP whose main campus is located at 2263 Avenue du Collège;

Sister cities

Notable people

- Peter Blaikie, lawyer

- Michaël Bournival, National Hockey League player

- Aline Chrétien, wife of Jean Chrétien

- Jean Chrétien, former Prime Minister of Canada

- Sylvain Cossette, singer

- Antoine Dufour, acoustic guitarist

- Paul Dumont, founding father of the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League

- Louise Forestier, singer and actress

- Martin Gélinas, National Hockey League player

- Jacques Lacoursière, historian

- Carole Laure, actress

- Bryan Perro, author, known for the Amos Daragon series

- Jacques Plante, National Hockey League player

- André Pronovost, National Hockey League player

- Camil Samson, leader of the Ralliement créditiste du Québec

Photos

- Some sectors

Lac-à-la-Tortue, Turtle Lake, seaplane docked, Chemin de la Vigilance

Lac-à-la-Tortue, Turtle Lake, seaplane docked, Chemin de la Vigilance

See also

- List of regional county municipalities and equivalent territories in Quebec

- Mayors of Shawinigan

- Saint-Maurice River

- La Mauricie National Park

- Wapizagonke Lake

- Lac-à-la-Tortue, sector of Shawinigan

- Grand-Mère, sector of Shawinigan

- Île Anselme-Fay

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Shawinigan (Ville)" (in French). Commission de toponymie du Québec. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- 1 2 "Répertoire des municipalités: Geographic code 36033". www.mamh.gouv.qc.ca (in French). Ministère des Affaires municipales et de l'Habitation.

- 1 2 https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&SearchText=Shawinigan&DGUIDlist=2021A00052436033,2021S05100750&GENDERlist=1&STATISTIClist=1,4&HEADERlist=0

- ↑ Shawinigan (Population centre), Quebec 2021 Census profile

- ↑ Territorial Division Act. Revised Statutes of Quebec D-11.

- ↑ Boudreau, Mathieu (2003). "Historique d'une forme urbaine centrale: l'évolution de la Place du Marché à Shawinigan" (PDF). Université de Montréal. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 3, 2023.

- ↑ Transactions 2004: Life, Learning and the Arts Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine, The Royal Society of Canada, November 19, 2004

- ↑ Power and Planning: Industrial Towns in Québec, 1890-1950 Archived 2007-06-27 at the Wayback Machine, CCA, 1996

- ↑ Alcan célèbre le centenaire de la production d'aluminium au Canada, Alcan Inc., November 1, 2001

- ↑ René Bergeron, Encadrement clérical en contexte d’urbanisation à Shawinigan, UQTR, April 1997

- ↑ Patri-Arch, Inventaire du patrimoine bâti de la ville de Shawinigan, Corporation culturelle de Shawinigan, July 2010

- ↑ Fabien LaRochelle, Shawinigan depuis 75 ans, Shawinigan, 1976

- ↑ J.J. Bellemare, 60 ans d'artillerie en Mauricie, Shawinigan, 1996

- ↑ "Shawinigan Falls Labor Wage Rate Highest in Province". The Shawinigan Standard. D.R. Wilson. 13 October 1954.

- ↑ "Premier Lesage Inaugurated Shawinigan Bridge Sunday". The Shawinigan Standard. D.R. Wilson. 5 September 1962.

- ↑ "Prohibition Repealed at Shawinigan South". The Shawinigan Standard. D.R. Wilson. 5 July 1961.

- ↑ "Tavern Keepers form Local Association". The Shawinigan Standard. D.R. Wilson. 9 May 1951.

- ↑ Chronologie de l’histoire des femmes au Québec et rappel d’événements marquants à travers le monde Archived 2013-11-14 at the Wayback Machine, 2006-07

- ↑ Wilson, Don (22 December 1970). "Greetings of the Christmas Season: Final Edition". The Shawinigan Standard. No. 27. p. 1.

It is with sincere regret and a heavy heart that we must ring down the curtain on the Standard, in its 42nd year of publication and what for the past few months has been the only English medium in the St. Maurice Valley.

- ↑ Incendie à l'ancien Hôtel de Lasalle, Marie-Ève Lafontaine, Le Nouvelliste, December 5, 2012

- ↑ L'Auberge Grand-Mère démolie, Marie-Ève Lafontaine, Le Nouvelliste, October 25, 2010

- ↑ Télesphore Racine, hôtelier (1859-1936), Omer Lemay, Société d'histoire et de généalogie de Shawinigan, 17 November 2008 Archived 8 July 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Fire Completely Destroys 50-Year Old Vendome Hotel". The Shawinigan Standard. D.R. Wilson. 16 April 1958.

- ↑ Le «Musée du premier ministre Jean Chrétien» ouvre ses portes, Daniel Lemay, La Presse, June 16, 2012

- ↑ Rapport du mandataire du Gouvernement - La réorganisation municipale du Centre-de-la-Mauricie, 2000

- ↑ Community Profiles, Statistics Canada, 1996

- ↑ Shawinigan includes Baie-de-Shawinigan, which was established in 1907 and merged in 1998.

- ↑ Grand-Mère includes Sainte-Flore, which was established in 1862.

- ↑ The Catholic parish municipality of Saint-Gérard-des-Laurentides was established in 1922.

- ↑ "Shawinigan, Quebec". Canadian Climate Normals 1971–2000. Environment Canada. 19 January 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ "Population and dwelling counts: Canada, provinces and territories, and census subdivisions (municipalities), Quebec". Statistics Canada. February 9, 2022. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- ↑ Lueur d'espoir pour l'aluminerie Alcan de Shawinigan, Presse canadienne, November 19, 2007 Archived January 19, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Belgo: le syndicat dépose un grief pour retarder la fermeture, Bernard Lepage, L'Hebdo du Saint-Maurice, December 20, 2007

- ↑ La fête nationale en Mauricie Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Karine Parenteau, Voir, June 22, 2006

- ↑ Vandalisme dans le parc de la rivière Grand-Mère, Clin d'oeil historique, L'Hebdo du St-Maurice, February 23, 2007

- ↑ Brasserie Le Trou du Diable

- ↑ L'église Saint-Bernard amorce sa deuxième vocation, Hugo Lemay, L'Hebdo du St-Maurice, October 28, 2007

- ↑ Annexe II Liste des églises paroissiales vendues dans les diocèses catholiques du Québec, 1965-2002, Archimède, Université Laval

- ↑ Bulletin des Amis de l'orgue de Québec, No. 100 - February 2005 Archived 2008-06-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ This figure does not include schools located in recently merged entities such as Shawinigan-Sud. For more details, see the article for each former municipality.

External links

- (in French) Shawinigan official site