| Shoal Creek, Austin, Texas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Mouth | |

• location | Colorado River |

• coordinates | 30°15′55″N 97°45′05″W / 30.265147°N 97.751436°W |

| Basin size | 36,000 acres (150 km2) |

Shoal Creek is a stream and an urban watershed in Austin, Texas, United States.

Shoal Creek has its headwaters near The Domain and runs in a southerly direction, soon reaching the intersection of Texas State Highway Loop 1, locally known as "MoPac Expressway" or simply "MoPac," [note 1] and Highway 183. It continues south, partly along Shoal Creek Boulevard and Lamar Boulevard, through the western part of downtown Austin to its end at Lady Bird Lake.

Shoal Creek is the largest of Austin’s north urban watersheds, encompassing approximately 8,000 acres (12.9 square miles). About 27% of the watershed is over the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Zone.[1] Its length is approximately 11 miles. It runs parallel to and between Waller Creek to its east and Johnson Creek to its west.

The creek is notable for its links to the history of Texas and Austin, its floods, and its scenery and parks just a few minutes from the Texas Capitol.

Course and tributaries

Shoal Creek has its origin on the west side of MoPac, with two springs, one called MCC/UT Spring and the other reportedly without a name. It runs eastward from there, crossing MoPac, and then enters a culvert that runs south. It then turns into a swampy area at MoPac and 183, and goes under 183 through a culvert, and Shoal Creek Boulevard begins to follow the course of the creek on its west side.[2][3]

About a mile or more later, the creek crosses Anderson Lane and the Spicewood Springs/Foster Branch joins it from the west.[2]

Perhaps a mile farther, the creek goes to the west of Beverly S. Sheffield Northwest Park, which is an important flood control facility, and it is joined from the west by the outflow from the Great Northern Dam, which is another one of the City of Austin’s Watershed Protection Department’s flood control projects. A minor tributary runs through the park from the east. At the downstream end of the park, Shoal Creek Boulevard crosses the creek and the street now follows the creek on the east side.[2]

More than 2 miles later, north of 45th Street, the Hancock Branch, which has already been joined by the Grover Tributary, enters from the east. This is the largest tributary of Shoal Creek and drains about 2 square miles of residential areas, the Brentwood, Abercrombie and Crestview neighborhoods.[2]

When the creek reaches 38th Street, Shoal Creek Boulevard ends, and the output of two springs enters the creek: the Beth Israel Temple Spring, just north of 38th, and Seiders Springs, just south. The year-round output of these springs creates a permanent pond north of 34th Street, which is the home of terrapins and fish.[2]

The creek now heads southeast to Lamar Boulevard, which it follows on the west for the next two miles. Big Boulder Spring, just south of 29th Street, is the next permanent source of creek water. There is also a seep or spring on the other side of Lamar Boulevard that drains into the creek through a culvert.[2]

Near 14th Street the creek goes under Lamar Boulevard and runs to the east of it for the rest of its course. At about 5th Street the creek makes a nearly right-angle bend to the east. The downtown part of the creek is channeled and many downtown streets run over it on bridges. Near 4th Street, the “lost” tributary, Little Shoal Creek, joins the main stream from the east. Little Shoal Creek was completely covered over by downtown development in 1917 [4][5]

At Third Street, the creek flows under the historic Third Street Railroad Trestle.

The creek flows into Lady Bird Lake (the Colorado River) between Nueces Street and West Avenue, after running past the Central Branch of the Austin Public Library.

The difference in elevation from its source to its mouth is approximately 320 feet.[6]

History

Arrowheads and other artifacts indicate that Native Americans occupied the Shoal Creek watershed 11,400 years ago.[7] There are also stories of attacks by the native people on early settlers. One Gideon White, who lived at Seiders’ Springs before the Seiders family settled there, was killed near his home in 1842 by a band of Native Americans.[4] A Mrs. Sarah Hibbins, who had been captured by natives when crossing the Colorado River in 1836, escaped them by night and followed the channel of Shoal Creek back to the Colorado, where she obtained help. Her two children, or perhaps only one of them, were rescued but her husband had already been killed. At that time, the village that would become Austin was called Dewitt’s Colony.[7][8]

There is supposed to be a Native American burial mound “near the old McCall Spring just west of the street now called Balcones Trail.”[4] Neither the spring nor the street exist now by those names.

In 1838, a few settlers lived along the creek’s mouth in the village of Waterloo when Mirabeau B. Lamar, later the second president of the Republic of Texas, arrived there. Lamar was looking for places that would be suitable for Texas’s new capital. He shot a buffalo and admiring the area’s scenic beauty, returned to Houston. The next year, when Lamar was president, a commission appointed by him recommended Waterloo as the capital of Texas.[9] Lamar wanted the capital to be on the “frontier” and have room to expand. He considered Shoal Creek to be the frontier and the land west of it to be Comanche territory.[10]

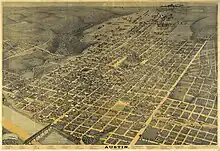

Shoal Creek was named by Edwin Waller, and its mouth roughly marked the western city limits of Austin in the original 1839 Waller Plan of the city.[4][7] In the "Bird's-Eye View" map by Augustus Koch, Shoal Creek is the large canyon on the left side.

When founded, the city issued land patents to several people, and others bought tracts of land. The Hancock (or Handcock) brothers, beginning around 1845, owned a huge tract spanning the creek, which stretched from what is now 45th street north about 2 miles to include the Allandale neighborhood. George Hancock apparently owned the southern and eastern part and John’s half was on the other side of the creek and to the north. This land was far outside the city limits at that time. John Hancock was a congressional representative. After he died, his family moved “into town” and sold the land, about 1896.[4]

In 1846, Louisa Maria White, the daughter of Gideon White, who as mentioned above was killed by Native Americans, married Edward Seiders, who was in the livery and grocery business. They took up residence in the cabin by the springs where her father had lived. The springs thereafter started to be called Seiders Springs, and the nearby oak grove was known as Seiders Oaks.[11]

In the 1850s, Governor Elisha M. Pease acquired a 365-acre tract west of downtown, including some of the Shoal Creek watershed, which he named Woodlawn Plantation. After the Civil War, General George Armstrong Custer, commanding the 2nd Wisconsin and the 7th Indiana Cavalry, was assigned to Austin in late 1865 and early 1866 as part of Reconstruction[7] and intended to use Governor Pease’s house, named Woodlawn, as his headquarters. Pease was out of the state at the time. The citizens of the city did not allow it. Custer’s men camped on the banks of Shoal Creek in the area that would become Pease Park.[4] Some of them died of cholera and were buried by the creek.[7]

Pease Park, originally twenty-four acres and part of Woodlawn Plantation, was given to the city in 1875 by former Governor Pease.[7]

Austin's first bridge was built on Pecan Street (now 6th Street) across Shoal Creek in 1865. It was a narrow iron footbridge, built by the United States Army, and could not carry wagon traffic. In 1887, a new, larger bridge across Shoal Creek was built to match the full 80-foot (24 m) width of Sixth Street and permit wagons to cross; this West Sixth Street Bridge is still in use today, and has since been added to the National Register of Historic Places.[12]

In the 1870s, Edward Seiders still owned the property around Seiders Springs but had moved back into Austin. (At that time, Seiders Springs was outside the city.) Seiders Springs had become an important recreation destination and Seiders built bath houses, picnic tables, and a dance pavilion there. He provided transportation to and from Austin for those who wanted to visit the springs.[11]

In the 1890s, there were rumors of buried treasure along the creek. Lights and digging in Pease Park at night was reported. Legend had it that Spanish gold was buried here.[13][5]

“Split Rock” was said to be used as a hiding place by outlaws, and there were also rumors of treasure buried in the vicinity. Split Rock is between 29th and 31st Streets. It was supposedly a hangout for children skipping school, who would go swimming at “Cat Hole” nearby or “Blue Hole” farther down the creek.[4] Split Rock was the subject of a painting, “Split Rock on Shoal Creek”, oil on academy board, by Hermann Lungkwitz (1813–1891).

The area to the west of the creek remained largely undeveloped into the 1920s.[4] There were no bridges crossing the creek north of 12th Street for many years, probably due to the width of the canyon there and the steepness of its sides. The 24th Street bridge was built in 1928, in less than a month by private parties, and widened in 1938. It is a Texas Historic Landmark.[7]

The city adopted a plan in 1927 that provided for ample parkland along Shoal Creek. This was prudent since the regular flooding makes it unwise to construct buildings along the creek. Nevertheless, a number of homes and businesses are within reach of the creek's floods. The entire watershed of Shoal Creek is now developed. This is labeled “urban stream syndrome” by the City of Austin on its website. “The impervious cover created with new buildings and roads prevents rainfall from soaking into the ground. Then we need to get all of this stormwater out of the way so our buildings and roads don’t flood. So we collect the water at inlets and concrete pipes and send it straight to the creek.” [14]

The City of Austin, perhaps in the 1950s, moved a "honeymoon cottage" that had belonged to O. Henry from the east side of downtown to a location along Shoal Creek near Gaston Avenue. This meant that the cottage was just down the hill from the exclusive neighborhood of Pemberton Heights. Apparently the City had plans to move the O. Henry house (now in a small park downtown) to this location as well. The honeymoon cottage burned to the ground on Dec. 23, 1956. Arson was suspected as this was the third fire in the cottage since it had been moved.[15]

In the 1950s, Janet Long Fish obtained the approval of the Austin City Council to construct a hiking trail from Pease Park to 39th Street, on her own time and using her own money. She walked the trail, leading a bulldozer, for four years.[7]

As of 2018, downtown development near the creek is proceeding quickly. Ballet Austin, at 501 West 3rd Street, once a landmark, is now surrounded by office and residential towers. The Austin Music Hall, 208 Nueces Street, was torn down and a 28-story office building, Third + Shoal, took its place. Office buildings and mixed-use towers are still being constructed. The “tallest residential tower west of the Mississippi”, The Independent, is here. The new central public library, near the mouth of the creek, is complete, and landscaping along the creek makes the waterway look more attractive.[9]

In May 2018, an elevated bank collapsed near 24th Street after heavy rains, which resulted in the closure of a segment of the just trail north of Pease Park. By January 2020, repair work stalled out due to an impasse between the city and the nearby property owners [16]

Population in the watershed was 59,011 in 2000 and is projected to be 78,759 in 2030. Impervious cover was estimated to be 52% in 2017. Austin's current codes allow up to 64% of impervious cover in the watershed.[17] Another source estimated impervious cover to be about 55% in 1996.[6]

Geology

The Shoal Creek watershed has three main types of rocks: the Georgetown Formation, the Del Rio Claystone, and the Buda Limestone.[18]

The bottommost of these, and hence the oldest, is the Georgetown Formation. It consists of alternating beds of thin, fine-grained limestone or limestone with marl. It is patchily or discontinuously distributed, with the patches separated by faulting. It varies from 13 meters (40 feet) in thickness to about 20 meters (60 feet) in different parts of Austin. The top of the Georgetown Limestone can be observed in Shoal Creek at Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard. Georgetown Limestone represents a number of open-shelf, subtidal environments of the early Cretaceous with varying faunas.[18]

The Del Rio Claystone is also more or less discontinuous in areas along Shoal Creek. The Del Rio is about 25 meters (75 feet) of dark olive to bluish-gray to yellow-brown pyritic clay containing gypsum. The clay contains illite, montmorillonite, and kaolinite. Fossils of Ilymatoqyra arietina, also known as Exogyra arietina, an extinct species of oyster from the Cretaceous, are common in this layer. Many very small species also are present, and the clay "lacks a normal bottom assemblage." This led Young et al. to conclude that it had been deposited in a lagoon with abnormal bottom conditions, which would account for the large amounts of pyrite. Upon weathering, the pyrite in the claystone reacts with water to produce sulfuric acid, which in turn reacts with calcite to produce the selenite (crystalline gypsum) found in Austin and elsewhere in Texas.[18]

The lower boundary of the Del Rio is “gradational” (not sharply defined) with the Georgetown Limestone, and the transition occurs through one to two meters (several feet). The upper boundary in the Austin area is sharply defined from ("disconformable with") the basal beach limestone of the Buda Formation.[18]

The Buda Limestone consists of 11.5 to 16 meters (35 to 50 feet) of nodular, soft and hard limestone. The bottom of this layer is a hard limestone composed of oyster shell fragments (oyster shell biosparite or grainstone). Most of the other beds are mollusk limestones, softer in the lower part and harder in the upper part.[18]

This limestone in the Austin area represents shallow subtidal and intertidal deposits. The bottom layer is a shoal or beach that spread across the Del Rio Formation and scoured it at the top. The rest of the formation is shallow subtidal storm deposits; the different beds seem to have been subjected to storms many times, and most of the fossils have been broken. However, there are fossils of burrowing animals present.[18]

The Buda Limestone can be visited at a variety of outcrops along Shoal Creek, especially along the Hike and Bike Trail. [18]

Springs are present all over Austin because porous rock (the Buda Formation, and Edwards Plateau limestone, farther west) covers thick clays/shales (for instance, the Del Rio claystone) which are more impervious to water. When the limestone over clay layers are exposed from the side, the water that percolates down through the limestone runs out on top of the clay.[19]

Big Boulder Spring shows how the local geology contributes to the formation of a spring. This spring is located on Shoal Creek just south of 29th Street. This is a gravity flow spring, with surface waters migrating down the overlying terrace deposits and Buda limestone, along vertical and horizontal fractures and faults and discharging at an opening where the fractured/faulted Buda Formation sits on top of the Del Rio Clay. Similar springs are present on the banks of Shoal Creek from the Pease Park area to near Koenig Lane.[20]

Seiders Springs is another spring near the banks of the creek. This spring may actually be two springs, obtaining their water from different sources, that are close to each other. One of the two springs is an "ebb-and-flow" spring which varies from 2 to 7 gallons per minute to between 50 and 62 gallons per minute.[21]

“The Balcones Fault is visible from the 34th street intersection, which was once a creek crossing for the early Native Americans and later one of Austin’s first public highways.” [13] Many outcrops and fault lines are visible in the Shoal Creek area. The elevation on the west side of the creek is higher than on the east, as West Austin is the beginning of the uplift of the Edwards Plateau, of which the Balcones Fault is the eastern boundary. Although the escarpment of the Balcones Fault is more likely to be gradual than sudden, there are places where it, or part of it, is well-defined.

University of Texas students discovered a fossil ichthysaurus on upper Shoal Creek near Northwest District Park during an archaeological dig. The ichthysaurus is now on display at the UT Natural History Museum.[13]

Water Chemistry

A study of samples taken up and down the watershed from September 1994 to April 1995 found that, as expected in a creek running mostly on a limestone bottom, calcium bicarbonate is present in the water. The investigators showed that there is a lower concentration of nitrate (NO3-) and other dissolved solids during “stormflow” events, compared to “base-flow” samples. Nitrate was from 0.19 to 0.75 mg/L in stormflow and 0.02 to 1.9 mg/L during base-flow. Total dissolved solids were from 16 to 187 milligrams per liter for stormflow samples, and from 213 to 499 milligrams per liter for base-flow samples.[6]

By analyzing oxygen and nitrogen isotopes, they concluded that the nitrate in stormflow samples came from the atmosphere, and from soil nitrate and ammonium fertilizer. Nitrate from base-flow samples had a different ratio of isotopes, suggesting an origin of soil nitrate, ammonium fertilizer, sewage and animal waste. The researchers decided that sewer lines in the creek corroborated this finding. Old sewer lines might leak, they said, and the excess of chlorine relative to sodium indicated sewage: a mixture of human waste and chlorinated water.[6]

They found fecal coliform bacteria, ranging from 1 to 84,000 colonies/100mL during stormflow, and less than 1 to 1,600 colonies/100mL during baseflow. The investigators compared this with fecal streptococci (stormflow: 1 to 310,000 colonies/mL; baseflow: less than 1 to 960 colonies/mL) and interpreted this to mean that the fecal bacteria came mostly from animal wastes, washed into the creek by rain.[6]

Ecology

The Shoal Creek watershed contains steep limestone slopes, thin soils, sparse vegetation and impervious cover.[6] About 30% of the watershed has tree canopy cover.[1]

Shoal Creek has ecological issues in common with most urban creeks: reduced vegetation, elevated streambank erosion, and impaired water quality. Nevertheless, the wildlife in and along the creek is varied because Austin itself is located at the intersection of four major ecological regions, and is very diverse ecologically and biologically.[22] The City of Austin now has a program of creating “grow zones”[23] in the watershed to re-establish plant life, which also benefits animal life. This creates a healthier “riparian buffer,” with benefits to the public as well.[24]

Shoal Creek is often referred to as an intermittent stream. However, there are places where it flows all year long, and pools that are present all year. When the creek appears to be dry, in reality there is water trickling through the limestone gravel that has piled up (the “shoals”). Where the creek appears to have a bed of limestone rock and there is no water trickling on the surface, a porous layer of rock underneath may have water trickling through. Numerous springs and seeps along the course of the creek contribute to a constant flow, which may be small but is always present except perhaps in years of severe drought.

Species lists

Plants

The organization iNaturalist, a joint initiative by the California Academy of Sciences and the National Geographic Society, posts online lists of species observed or collected in or near Shoal Creek. The lists have been combined here, and not all of the species are named.

Plants: Trees include Ulmus crassifolia (Cedar Elm), Quercus fusiformis (Texas live oak), Ungnadia speciosa (Mexican buckeye), Melia azedarach (Chinaberry), Acer negundo (boxelder maple), Ipomopsis rubra (standing cypress), Prosopis glandulosa (honey mesquite), Sophora secundiflora (Texas mountain laurel), Platanus occidentalis (American sycamore), Sapindus saponaria (Western soapberry), Juniperus ashei (Ashe juniper), Taxodium distichum (Bald cypress), Cercis canadensis (Eastern Redbud), Eriobotrya japonica (Loquat), Magnolia grandiflora (Southern Magnolia), Triadica sebifera (Chinese Tallow), Punica granatum (Pomegranate), Quercus stellata (Post Oak), Quercus muehlenbergii (Chinkapin Oak), Albizia julibrissin (Persian Silk Tree), Morus rubra (Red Mulberry), Ulmus americana (American Elm), Ailanthus altissima (Tree of Heaven), Morus alba (White Mulberry), Quercus phellos (Willow Oak), Cordia boissieri (Texas Wild Olive), Prunus mexicana (Mexican Plum), Quercus falcata (Southern Red Oak), Diospyros texana (Texas Persimmon), and Quercus shumardii (Shumard's Oak).[25][26][27][28]

Shrubs, bushes and small trees include Vachellia farnesiana (sweet acacia), Berberis trifoliolata (Agarita), Lantana montevidensis (creeping lantana), Parkinsonia aculeata (Mexican palo verde), Lantana camara (common lantana), Nandina domestica (Heavenly bamboo, an invasive species escaped from gardens), Ilex vomitoria (Yaupon Holly), Maclura pomifera (Osage orange), Sabal minor(Dwarf Palmetto), Ligustrum quihoui (Quihoui privet, another escaped species), and Ptelea trifoliata (common hoptree).[25][26][27][28]

Vines include Lonicera japonica (Japanese honeysuckle, not native), Campsis radicans (American trumpet vine), Passiflora lutea (Yellow Passionflower), and Parthenocissus quinquefolia (Virginia Creeper).[25][26][27][28]

Water plants include Arundo donax (giant reed or Carrizo cane) and Cyperus involucratus (Umbrella papyrus).[25][26][27][28]

Cacti include Opuntia engelmannii (Texas prickly-pear) and Cylindropuntia leptocaulis (Christmas cholla).[25][26][27][28]

The list assembled by iNaturalist includes many wildflowers, notably Rudbeckia hirta (black-eyed Susan), Gaillardia pulchella (Indian blanket), Monarda citriodora (lemon beebalm), Coreopsis tinctoria (plains coreopsis), Solanum elaeagnifolium (silverleaf nightshade), Lupinus texensis (Texas Bluebonnet), Lindheimera texana (Texas yellow star), Callirhoe involucrata (winecup mallow), Oenothera speciosa (Pinklady or pink evening primrose), Verbena halei (Texas Vervain), and Malvaviscus arboreus (Turk's cap).[25][26][27][28]

The list of plants also includes the epiphytes Tillandsia recurvata (small ballmoss) and Tillandsia usneoides (Spanish moss).[25][26][27][28]

The lists do not include any aquatic plants or algae, but the City of Austin has a list, with photos, of wetland plants in the Austin area.[29]

At the creek’s junction with Lady Bird Lake, there are numerous non-native elephant ears (Colocasia esculenta).[29]

The vegetation in the creek area is typical of Austin. Large live oaks (Quercus virginiana) provide year-round shade on the hike-and-bike trail. One group of oaks in Pease Park is festooned with Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides). Other native trees include sycamore, pecan, hackberry and juniper. Bamboo, a non-native pest, has a large stand south of 29th Street on the hike-and-bike trail. There is a program in the works to eradicate the bamboo with herbicide.[30]

Animals

Invertebrates

Crustaceans: Aquatic animals include Procambarus clarkii (Red Swamp Crayfish) and the amphipod Talitroides topitotum (Tramp Hopper).[25][26][27][28]

Armadillidium vulgare, the Common Pillbug is listed.[25][26][27][28]

Insects

Butterflies and moths: Papilio polyxenes (Black Swallowtail), Hylephila phyleus (Fiery Skipper), Agraulis vanillae (Gulf Fritillary), Libytheana carinenta (American Snout), Strymon melinus (Gray Hairstreak), Zerene cesonia (Southern Dogface), Hyphantria cunea (Fall Webworm Moth), and Petrophila jaliscalis, the "Jalisco Petrophila."[25][26][27][28] The larvae of the last species are aquatic, living within a silken web in the water. They are associated with intermittent streams.[31]

Walkingsticks: Anisomorpha ferruginea (Northern Two-striped Walkingstick)[25][26][27][28]

Hymenoptera: Polistes exclamans (Guinea Paper Wasp), Sceliphron caementarium (Black-and-yellow Mud Dauber), Apis mellifera (Western Honey Bee), Xylocopa virginica (Eastern Carpenter Bee), Pseudomyrmex gracilis (Graceful Twig Ant), Solenopsis invicta (Red Imported Fire Ant).[25][26][27][28]

Beetles: Diabrotica undecimpunctata (Spotted Cucumber Beetle), Harmonia axyridis (Asian Lady Beetle), Hippodamia convergens (Convergent Ladybeetle), Euphoria sepulcralis (Dark Flower Scarab).[25][26][27][28]

Grasshoppers: Chortophaga viridifasciata (Green-striped Grasshopper).[25][26][27][28]

Leafhoppers: Homalodisca vitripennis (Glassy-winged Sharpshooter), Oncometopia orbona (Broad-headed Sharpshooter).[25][26][27][28]

Shoal Creek has an abundance of dragonflies and damselflies. iNaturalist lists these: Libellula croceipennis (Neon Skimmer), Pachydiplax longipennis (Blue Dasher), Argia immunda (Kiowa Dancer), Argia plana (Springwater Dancer), Argia sedula (Blue-ringed Dancer), and Argia translata (Dusky Dancer).[25][26][27][28]

Other insects include Labidura riparia (Shore Earwig), Stagmomantis carolina (Carolina Mantis), Panorpa nuptialis (Orange-banded Black Scorpionfly), and Parcoblatta americana (Western Wood Cockroach).[25][26][27][28]

Arachnids: The only arachnid listed by iNaturalist is Anasaitis canosa, the Twinflagged Jumping Spider.[25][26][27][28]

Vertebrates

Fish: iNaturalist lists Herichthys cyanoguttatus (Texas Cichlid).[25][26][27][28]

The creek also has sunfish (Lepomis sp.), and Micropterus salmoides (Largemouth Bass) near its mouth. These fishermen also found Mexican tetra (Astyanax mexicanus) and the Texas cichlid.[32]

Another fisherman specifically mentions “Redbreast” (Redbreast sunfish, Lepomis auritus), and Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus). He also mentions “bass” and describes the spawning beds of the Rio Grande (Texas) Cichlid, with a picture of one that he caught. This fish is also called the “Rio Grande Perch.” [33]

A fish common from the lower to the upper reaches of Shoal Creek is the Texas mosquitofish, Gambusia affinis. The City of Austin introduces it for mosquito control and it also occurs naturally.

Amphibians: Listed by iNaturalist: Incilius nebulifer (Gulf Coast Toad) and Eleutherodactylus cystignathoides (Rio Grande Chirping Frog), Acris blanchardi (Blanchard's Cricket Frog) and Eleutherodactylus marnockii (Cliff Chirping Frog). [26][27]

“The Jollyville Plateau Salamander (Eurycea tonkawae) is found in the Spicewood Springs tributary of Shoal Creek. It is listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act."[34] The health of this species is strongly affected by the flow of the springs in which they live. There was a drought in 2011, but salamander populations increased in 2014 when rainfall resumed (referring to Bull Creek, another watershed in which this salamander is found.)[35]

A species of amphibian that is likely to be present is the Bullfrog (Lithobates [Rana] catesbeiana).

Reptiles: Listed by iNaturalist: Anolis carolinensis (Green Anole), Hemidactylus turcicus (Mediterranean House Gecko), Sceloporus olivaceus (Texas Spiny Lizard), Rena dulcis (Texas Blind Snake), Haldea striatula (Rough Earthsnake), Nerodia erythrogaster (Plain-bellied Watersnake), Thamnophis marcianus (Checkered Garter Snake), Tropidoclonion lineatum (Lined Snake), Trachemys scripta (Pond Slider), Thamnophis proximus (Western Ribbon Snake), Apalone spinifera (Spiny Softshell), Nerodia rhombifer (Diamondback Watersnake), Tantilla gracilis (Flat-headed Snake), Storeria dekayi (Dekay's Brownsnake), Scincella lateralis (Little Brown Skink), Pseudemys texana (Texas Cooter), Pantherophis obsoletus (Western Rat Snake), and Chelydra serpentina (Common Snapping Turtle).[25][26][27][28]

Birds: Listed by iNaturalist: Butorides virescens (Green Heron), Quiscalus mexicanus (Great-tailed Grackle), Mimus polyglottos (Northern Mockingbird), Egretta thula (Snowy Egret), Ardea alba (Great Egret), Cardinalis cardinalis (Northern Cardinal), Columba livia (Rock Dove, a.k.a. Pigeon), Zenaida asiatica (White-winged Dove), Cyanocitta cristata (Blue Jay), Sturnus vulgaris (European Starling), Passer domesticus (House Sparrow), Cardinalis cardinalis (Northern Cardinal), Thryothorus ludovicianus (Carolina Wren), Nyctanassa violacea (Yellow-crowned Night-Heron), Lanius ludovicianus (Loggerhead Shrike), Melanerpes carolinus (Red-bellied Woodpecker), Aix sponsa (Wood Duck), Corvus brachyrhynchos (American Crow), Myiopsitta monachus (Monk Parakeet), Bombycilla cedrorum (Cedar Waxwing), and many others.[25][26][27][28]

The Shoal Creek Nature Conservancy conducted a bird walk in 2014 and saw or heard the following species: Wood Duck, Green Heron, Red-shouldered Hawk, Red-tailed Hawk, Spotted Sandpiper, Rock Pigeon, White-winged Dove, Mourning Dove, Chimney Swift, Red-bellied Woodpecker, Great Crested Flycatcher (heard), Blue Jay, Barn Swallow, Carolina Chickadee, Tufted Titmouse, Carolina Wren, Blue-gray Gnatcatcher, Northern Mockingbird, European Starling, Cedar Waxwing, Orange-crowned Warbler, Nashville Warbler, Clay-colored Sparrow, Lincoln’s Sparrow (heard), Summer Tanager, Northern Cardinal, Great-tailed Grackle, Lesser Goldfinch, House Sparrow.[36]

Mammals:

Listed by iNaturalist: Sciurus niger (Fox squirrel), Odocoileus virginianus (White-tailed Deer), Canis latrans (Coyote), Didelphis virginiana (Virginia Opossum), Procyon lotor (Common Raccoon), Mephitis mephitis (Striped Skunk), Otospermophilus variegatus (Rock Squirrel), Oryctolagus cuniculus (European Rabbit), and Rattus norvegicus (Brown Rat).[25][26][27][28]

Flooding

The City of Austin is located in "Flash Flood Alley," an area of Texas that may be subject to intense rain caused by moisture from the Gulf of Mexico, cold fronts from the north and masses of air from the west.[37]

Since Shoal Creek runs through the downtown area of a major city, it has the potential to cause enormous damage by flooding. This is exacerbated by the flatness of downtown Austin, which is the flood plain of the Colorado River after it descends from the Edwards Plateau. As a result of erosion by the Colorado River, Shoal Creek’s large canyon does not exist south of 12th Street. The Colorado River has eroded and flattened this terrain. There is still an elevation to the west of the creek, but there is little to the east, where the center of downtown lies. Downtown, the creek runs in a channel 30 to 50 feet wide and 15 to 20 feet deep, which takes a sudden bend to the east at 4th Street. The canyon walls upstream constrain a flood but this small channel is not adequate to keep the creek from overflowing into the streets. There are 339 flood detention basins in the watershed, and 100 water quality treatment basins. They manage only about 21% of the impervious cover, however. In the 100-year floodplain, there are 274 "inundated" structures. In the 25-year floodplain, there are 127; in the 10-year floodplain, 67; and 6 in the 2-year floodplain. In all, there are 655 structures within the 100-year floodplain. Most of the watershed, 71%, was developed before the 1991 Urban Watersheds Ordinance regulations. There are 54 roadways within the 100-year floodplain with 46 inundated by the 100-year, 41 inundated by the 25-year, 35 inundated by the 10-year, and 11 by the 2-year floods.[1] [note 2]

Shoal Creek has had numerous floods throughout Austin’s history. A major one occurred in 1869. A flood in 1915 killed 23 people along Shoal Creek, and another 12 along Waller Creek.

On Memorial Day, May 24, 1981, the rain that had begun the day before started falling much more heavily after dark. Parts of the Shoal Creek watershed received 11 inches of rain in 3 hours. The water flow in the creek, normally about 90 gallons per minute, increased to 6.55 million gallons [note 3] per minute. Thirteen people lost their lives, many had to be rescued, hundreds of houses were destroyed, and Shoal Creek washed dozens of cars into its channel, many from car dealerships next to it on 5th and 6th Streets. This was called a “100-year flood.” [38]

As a result of this flooding, voters approved a drainage fee and millions of dollars in bonds in 1981, 1982, and 1984 to fund flood control and drainage improvement projects. Since the 1981 Memorial Day Flood, the City of Austin has spent over $65 million to construct detention ponds, make channel modifications, and construct other flood mitigation solutions in the Shoal Creek watershed. Millions more have been spent to purchase properties.[9]

The flood control measures did not significantly change the creek downtown. Following heavy rains, a second large Memorial Day Flood struck in 2015. (see photo) The damage was “depressingly similar” to the flood in 1981.[9]

Any larger-than-ordinary rain is too much for the capacity of the creek’s channel downtown. Two low-water crossings on 9th and 10th streets between Lamar Blvd. and West Ave. have been closed nine times between 2010 and 2016.[34]

Six hundred and fifty-seven structures are within Shoal Creek’s 100-year floodplain. This is 15% of all structures in floodplains city-wide.[34]

Ninety-six structures near the Hancock Branch and Grover Tributary are at risk during a 100-year flood. The Brentwood neighborhood was developed during the 1940s and 1950s. The drainage infrastructure that was constructed is inadequate. Undersized channels, culverts, and storm drains result in street and structure flooding on a frequent basis.[34]

"As the Hancock Tributary is directly downstream of the Brentwood neighborhood, any solution to the localized flooding in Brentwood must be carefully designed so as not to worsen flooding in this area."[34] Actually, as one can see on a map, the Hancock tributary originates in the Crestview neighborhood north of Brentwood, and flows through the Brentwood neighborhood. The Hancock Branch runs down the median of a street named Arroyo Seco (“Dry Creek”). Heavy rains will flood the entire street. The Grover Tributary joins the Hancock Branch from the east near Koenig Lane and Arroyo Seco.

Development of the neighborhood also altered the erosion patterns of Hancock Branch and Grover Tributary. Particularly, the Grover Tributary runs through underground drains through much of its length, or constructed channels as shown in the picture. The danger area along Joe Sayers Street is southwest of the place the tributaries meet. In fiscal year 2017, the city began a preliminary engineering study for a project to correct multiple defects in the drainage infrastructure in this area.[34]

Although this is serious, the City of Austin says that Lower Shoal Creek between 15th Street and Lady Bird Lake is the worst flooding problem in the city.[34]

Besides the loss of lives and property, flooding erodes the banks of the creek. On Friday, May 4, 2018, heavy rains caused part of the canyon to collapse near the 2500 block of North Lamar along the west bluff of Shoal Creek. The landslide damaged part of the Shoal Creek Trail and some homes on the bluff lost part of their backyards, which fell down the slope.[39] This occurred just 2 weeks after an official celebration, on April 20, of the completion of the City’s Shoal Creek Restoration Project.[40]

There were no injuries. The landslide damaged city parkland at Pease Park and about 300 feet of the hike-and-bike trail. It also “buckled” a city wastewater line beneath the trail. Crews put in pumps to redirect wastewater flow to a working part of the sewer system until there is a permanent solution. Mike Kelly, Austin Watershed managing engineer, said that the bluff above Shoal Creek is made of Buda limestone over an unstable Del Rio clay formation. When the clay moves beneath the limestone, it causes fractures that can eventually lead to slope failures.[39] On that day, Shoal Creek crested at about 12.37 feet around noon, according to the Lower Colorado River Authority.[39]

On April 16, 2019, after spending $1 million on a year-long study of the landslide, the City of Austin estimated that repairing the damage and stabilizing the slope would cost $8 to $16 million. The top of the slope had moved again just a few weeks before the announcement.[41]

Soon after the City released the repair estimate, floods in early May 2019 damaged more of the trail, causing it to slide into the creek. The landslide area was considered so dangerous that it was not possible to do any work to repair it.[42] In addition, a man who was bathing in the creek at 9th Street was swept away by the flood and drowned. His body was found in Lady Bird Lake.[43]

Following the flooding in May 2019, a new repair estimate was $12.5 million for design and construction costs and $7.5 million in contingency funding.[44]

In January 2020, the City of Austin announced that it was unable to reach agreement with the landowners whose backyards partially fell into the creek bed. As a result, the City was unable to acquire easements to stabilize the cliff and maintain it. The city has four goals now: to clear the debris from the creek and allow the water to flow more freely, to widen the creek in places, to replace the wastewater line that was damaged by the landslide, and to construct a new segment of the hike-and-bike trail, about 500 feet long, to replace the part that was destroyed.[45] In January, 2022, the city decided that the trail would not be repaired or replaced. Users of the trail would no longer go along Shoal Creek in the slide zone but would use the sidewalk along Lamar Boulevard, which would be improved. This sidewalk had been used as a trail detour since the slide blocked the trail.[46]

Flood control

As mentioned earlier, the 1981 Memorial Day flood was the impetus for Austin voters to approve bonds and spend millions to control flooding. In addition to rebuilding bridges, increasing the size of culverts and ditches and turning flooded properties into open space, the city built some large projects.

Great Northern Dam, between MoPac and Shoal Creek Boulevard, impounds a retention pond for all of the watershed to the west of Shoal Creek up to the Spicewood tributary. This includes rain that falls on MoPac itself and is collected in the ditches to the side of the highway. The land rises steeply west of the impoundment—this is the edge of the Balcones Fault. The dam and its impoundment are on a minor tributary of Shoal Creek that is usually dry.[47] The dam was first constructed at an unknown date. It was considered "high-hazard" and was modernized after studies between 2003 and 2008.[48][note 4]

Beverly S. Sheffield Northwest District Park was renovated by the City’s Watershed Protection Department after the 1981 flood. Its tennis courts, parking lot, a grassy field, and a baseball field, totaling approximately 10 acres, are for flood control. When the creek rises to approximately 10 feet, the water runs over a wall into the park and then drains back at a slower rate.[9]

The park is the site of an old quarry, from which came the limestone blocks for the first Texas Capitol building, constructed in 1853.[50] Since it was already an excavation, it was not hard to adapt it to retain floodwaters by building the wall in the picture and levees.

In 2014, the Watershed Protection Department, based on a study proposal made by the Army Corps of Engineers in 1991, suggested a 26-foot diameter tunnel that would run 6,000 feet from 19th Street to the lake at an estimated cost of $133 million. Its proposed inlet was to be within Pease Park. The City of Austin has used this means of flood control before. A tunnel routes flood waters in Barton Creek around the Barton Springs Pool. As of 2018, the City is completing a similar tunnel to prevent flooding on Waller Creek, and it has problems.[51]

The Pease Park Conservancy opposed the tunnel. In a 2016 press release, it urged the City Council to “only consider solutions that do no [sic] alienate any dedicated parkland” and to not waste taxpayer dollars on “studying a flood control system that will be dead on arrival and never built.”[9]

The Conservancy noted that the land was stipulated to be a park, so therefore “taking portions of the park for other divergent uses could violate the terms of that deed and be certain to subject the City to costly litigation.”[9]

Another way to control floods would be to retain the floodwaters upstream. The flood control measures at Northwest District Park and at Great Northern Dam did not prevent flooding in 2015. Greater retention capacity would be hard to create. The properties in the neighborhoods around Shoal Creek are deemed very desirable and would be costly to obtain.

Another possibility is to make areas that are floodable, i. e. designing and contouring areas such as parking lots, recreational sports fields, parks, etc. to accept periodic inundation. Downtown, it seems that this is recognized as a solution, as office buildings are built to the edge of the channel of the creek. Presumably these buildings, which have open-air cafes and mixed-use spaces on the banks of the creek, expect to be flooded from time to time. House Park, a football field near the creek at 15th Street, floods regularly.

The State of Texas owned a 75-acre tract along the creek south of 45th Street. This was sold to developers in 2014,[52] and Austin approved a development plan in 2018. The major issue brought up by the City in setting requirements for development was the creation of “affordable housing,” not flood control. This was despite some warnings that more development and impervious cover in the watershed would make flooding worse. As a result, the final plan has little or no flood control facilities: neither retention nor lowered floodable areas. However, buildings are set well away from the creek, which runs through the park that is part of the development.[53]

The development plan approved by the City did propose “No modification to the existing 100-year floodplain” and “Direct storm water runoff from impervious surfaces to a landscaped area at least equal to the total required landscape area."[54] It is not clear what effect these requirements will have.

Two other possible solutions to flooding are cisterns (smaller but more numerous than retention ponds) to take overflow water during flooding and the possibility of storing water underground in aquifers, perhaps by creating enormously deep dry wells. This would raise the issue of pollution of the aquifer, but might solve flooding and recharge the aquifer at the same time.

The City of Austin is establishing “flood cameras” to have some idea of when roads should be closed to protect people. Most of these cameras will be on rural low-water crossings, but four points along Shoal Creek are identified on the map: The ramp from Northbound 183 to MoPac, MoPac at Steck (7500 N. MoPac), Shoal Creek at Lamar and West 9th Street at North Lamar.[55] [56]

The webpage for the continuing study of these options (officially called the Shoal Creek Flood Mitigation Study, is maintained by the City of Austin, Watershed Protection Department.[57]

Pollution

Shoal Creek’s water quality is rated as fair on the City’s Environmental Integrity Index (EII).[1]

As noted above, the City of Austin, back when little attention was paid to environmental issues, laid sanitary sewer lines in the creek. The flooding on May 4, 2018, caused “buckling” in the sewer line near the 2500 block of North Lamar. It is not clear how much sewage escaped.

While chronic pollution in the creek is perhaps not a tractable problem due to its location in an urban area, the City's Watershed Protection Department attends to reports of spilled substances quickly. [58]

Construction near the creek is a potential source of pollution, and the city investigates after someone reports changes in the water. In one instance, the water was reported to be “murky.”[59]

In another case of murky water, the City filed a Class C misdemeanor complaint against a contractor. This time, the project manager and the contractor were apparently aware of problems and did not correct them. The court record says that 'crews tried a "number of ways to contain [the water] and clean it" but efforts have "continually failed."'[60]

The City’s Watershed Protection Department’s Shoal Creek Restoration Project is not only establishing “grow zones,” reducing erosion and planting vegetation, but also fighting pollution that enters the creek in storm runoff. The Department is installing rain gardens, biofiltration ponds and meadows, and vegetated swales to improve water quality.[61] In 2016, the project was expected to be complete by summer of that year.[62]

Besides sewers, construction and miscellaneous spills, there is the problem of trash.

Recreation

Shoal Creek’s Hike-and-Bike Trail is the oldest trail in Austin. It was started by Janet Fish in the late 1950s, who hired a bulldozer and operator and made a trail through Pease Park.[7][63] More of it was built by volunteers in the 1960s and improved by the City in the 1970s. Parts were rendered impassable by the flooding on May 4, 2018. At one time it was possible to walk from 38th Street to Lady Bird Lake on the trail, with the exception of one block on 31st Street where steep canyon sides and private property force a hiker to use the street. More recently, following a landslide in 2019, a portion of the trail is now closed and rerouted along existing sidewalks along North Lamar Boulevard. Besides the aforementioned block and this, it is possible to commute entirely using the trail from 38th to Lady Bird Lake, however, some portions are fairly risky for bikers, due to their narrow width and cave embankments restricting height above.

Along an upper portion of the creek, there is a dirt and gravel trail that runs along a portion of the greenbelt between Allandale Rd. and Bull Creek Rd. along Shoal Creek Blvd.

Pease Park is the site of the annual Eeyore’s Birthday Party which is traditionally held on a Saturday near the beginning of May. When the date is announced, a rain date is also announced.

The trail is used daily by walkers and bicyclists, some of whom use it to commute to jobs downtown. The plan of the Shoal Creek Conservancy is to extend the trail to the Domain, where the creek has its headwaters. There, eventually, it would connect to the Walnut Creek Trail and form a 30-mile trail loop with much of the City of Austin inside.[64][65][3]

The construction of Austin's new Central Library and the redevelopment of downtown Austin presented an opportunity to make Lower Shoal Creek (defined as the creek from 5th Street to Lady Bird Lake) into a "signature urban green space." The Task Force's report noted that near Lady Bird Lake, the creek is usually confined to its channel, and also that there is room for significant improvement in the stream's appearance. They proposed removing obsolete infrastructure, standardizing the appearance of the banks using large limestone boulders for a natural look, and planting vegetation. The Central Library was completed and opened in 2017.[37][note 5]

Notable people associated with the creek

- Mirabeau B. Lamar

- Elisha M. Pease

- Janet Fish - “In the late 1950s, she took the money she had been given to purchase a new car, hired a bulldozer operator and began creating the first Hike and Bike trail..[I]n 2006 the new pedestrian bridge across Shoal Creek at 29th street was dedicated in her name."[63]

Organizations

- City of Austin

- City of Austin, Watershed Protection Department

- Shoal Creek Conservancy[67]

- Pease Park Conservancy[68]

Notes

- ↑ This highway will be called MoPac throughout this article, because that's what people call it. Nobody calls it Loop 1, which is what the signs say. The Missouri Pacific Railroad is also called "Mopac" but more usually the "MoPac Railroad" or "MoPac tracks."

- ↑ A roadway or structure within the 2-year floodplain is also within the 100-year floodplain. It seems that the authors did not count roadways or structures more than once. The numbers are hard to reconcile.

- ↑ This is approximately the volume of 10 Olympic size swimming pools.

- ↑ The dam is called Great Northern Dam not because it is especially great or very far north, but because the railroad tracks that go between the dam and MoPac (Texas Loop 1) were once part of the International-Great Northern Railroad, which gave its name to Great Northern Boulevard. The dam is adjacent to Great Northern Boulevard and takes its name. The Great Northern Railroad was sold to the Missouri Pacific Railroad, from which comes the name MoPac.[49]

- ↑ Despite the Task Force's sanguine assurance that the creek would be confined to its channel here, the new Central Library keeps all of its books on the third floor or above.[66]

References

- 1 2 3 4 The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment, "SHOAL CREEK WATERSHED PROTECTION PLANNING SCOPING & FUNDING STRATEGIES," prepared for the Shoal Creek Conservancy, September 2016. Online at http://shoalcreekconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SCC-Meadows-Scoping-Funding-Strategies-Report-Final-with-Appendices.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Shoal Creek Conservancy, Map, Shoal Creek Conservancy, undated. Online at https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/about-shoal-creek/map/

- 1 2 Shoal Creek Conservancy, "Shoal Creek Trail: Vision to Action Plan," Shoal Creek Conservancy, 2018. Online at https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DRAFT-SC-REPORT-2018.06.21-digital.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Leila Downs Clark, The History of Shoal Creek, Bryker Woods Neighborhood Association, 1954 https://brykerwoodsaustin.wordpress.com/our-history/the-history-of-shoal-creek/

- 1 2 Don Tate II, Below Austin's Surface, Austin American-Statesman, Undated, online at http://alt.coxnewsweb.com/statesman/pdf/08/0815UndergroundFinal.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Patricia B. Ging, Roger W. Lee, and Steven R. Silva, WATER CHEMISTRY OF SHOAL CREEK AND WALLER CREEK, AUSTIN, TEXAS, AND POTENTIAL SOURCES OF NITRATE. U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY, Water-Resources Investigations Report 96-4167. Prepared in cooperation with the CITY OF AUSTIN. Austin, Texas, 1996. Online at: https://pubs.usgs.gov/wri/1996/4167/report.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Pease Park Conservancy, "Park History," Pease Park Conservancy, 2017(?). Online at https://peasepark.org/park-history

- ↑ Indian Depredations In Texas: Reliable Accounts Of Battles, Wars, Adventures, Forays, Murders, Massacres, Etc., Together With Bio- Graphical Sketches Of Many Of The Most Noted Indian Fighters And Frontiersmen Of Texas. BY J. W. WILBARGER. SECOND EDITION. AUSTIN, TEXAS: Hutchings Printing House, 1890. Online at https://archive.org/stream/indiandepredatio00wilb/indiandepredatio00wilb_djvu.txt

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jack Murphy, Watershed Urbanism: Shoal Creek’s Infrastructural Future. Mar. 30, 2017 Online at http://offcite.org/watershed-urbanism-shoal-creeks-infrastructural-future/

- ↑ Shoal Creek Conservancy, “Shoal Creek Trail: Vision to Action Plan [Draft], June 21, 2018, pg. 25. Online at https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/DRAFT-SC-REPORT-2018.06.21-digital.pdf

- 1 2 Texas A&M Forest Service, "Seiders Oaks," Texas A&M Forest Service, 2012. Online at: http://texasforestservice.tamu.edu/websites/FamousTreesOfTexas/TreeLayout.aspx?pageid=16141.

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Registration Form, West Sixth Street Bridge at Shoal Creek. Online at https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/places/pdfs/14000499.pdf

- 1 2 3 City of Austin. Creekside Story: Shoal Creek. 2012. Online at http://www.austintexas.gov/blog/shoal-creek

- ↑ City of Austin, Creekside Story: What’s the rush? Slowing stormwater down…from pipes to swales to creeks, 2015. Online at http://www.austintexas.gov/blog/what%E2%80%99s-rush-slowing-stormwater-down%E2%80%A6from-pipes-swales-creeks

- ↑ Michael Barnes, Unhappy twist: O. Henry’s Austin honeymoon cottage went up in flames: Reader remembers the fire on Gaston Avenue, Austin American-Statesman, July 07, 2018. Online at https://www.mystatesman.com/news/unhappy-twist-henry-austin-honeymoon-cottage-went-flames/u9w6ywOM98vjsOWfDSrrrN/

- ↑ "After negotiations fail, city rethinks Shoal Creek landslide repair".

- ↑ City of Austin, Watershed Protection, Analysis of Proposed Impervious Cover Entitlements for CodeNEXT, 7/3/2017. Online at https://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Planning/CodeNEXT/WPD_CodeNEXT_IC_Analysis_final.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Keith Young, Guidebook to the Geology of Travis County, Chapter 2, Rocks of the Austin Area. The Student Geology Society, University of Texas, 1977 (rendered to HTML 1996) Online at: http://www.library.utexas.edu/geo/ggtc/toc.html

- ↑ Alan J. Cherepon, P.G., P.H., Sylvia R. Pope, P.G. and Scott E. Hiers, P.G. Less Frequented Springs of the Austin Area, Texas. Austin Geological Society Spring Field Trip, February 25, 2017. 2017. Online at: ftp://ftp.ci.austin.tx.us/Forms_ERI_Environmental_Review/AGS_Guidebook2017/SpringsGB37_120716_FINALdraft.pdf

- ↑ Alan J. Cherepon, Select Springs of the Austin Area: Descriptions and Associated Hydrogeology. Volume 4 — Austin Geological Society Bulletin, 2010. Online at: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56e481e827d4bdfdac7fbe0f/t/56f87ec74c2f85720ce5e87c/1459125970502/Cherepon%2C+2010%2C+Select+Springs+of+the+Austin+Area--Descriptions+and+Associated+Hydrogeology.pdf

- ↑ Peterman, Randy, "The Flow of Seiders Springs," Shoal Creek Conservancy, November 20, 2017. Online at: https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/the-flow-of-seiders-springs/

- ↑ Vines, Robert A. (1984). Trees of central Texas. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-78058-3.

- ↑ City of Austin, Creekside Story, "Grow Zones," 2012. Online at http://www.austintexas.gov/blog/grow-zones

- ↑ City of Austin, Watershed Protection, Riparian Zone Restoration: Shoal Creek Greenbelt, 2012. Online at http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Watershed/riparian/shoalcreek-greenbelt-factsheet.pdf

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 iNaturalist, Pease Park and Shoal Creek Greenbelt Check List, 2017. Online at https://www.inaturalist.org/check_lists/121974-Pease-Park-and-Shoal-Creek-Greenbelt-Check-List

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 iNaturalist, Shoal Creek Watershed, 2017. Online at https://www.inaturalist.org/places/shoal-creek-watershed

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 iNaturalist, Pease Park and Shoal Creek Greenbelt, 2014. Online at https://www.inaturalist.org/places/pease-park-and-shoal-creek-greenbelt

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 iNaturalist, Shoal Creek 500ft buffer, 2017. Online at https://www.inaturalist.org/places/shoal-creek-500ft-buffer

- 1 2 City of Austin, Watershed Protection Department, "Central Texas Wetland Plants", undated. Online at: http://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Watershed/blog/creekside/WetlandGuideByFamily_WEB.pdf

- ↑ Shoal Creek Conservancy, "Now Underway: Bamboo Removal and Restoration Project, 2014. Online at https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/bamboo_project/

- ↑ Bugguide, "Species Petrophila jaliscalis - Hodges#4775". 2007, 2022. Online at https://bugguide.net/node/view/99067

- ↑ Matthew Bey, Adventures Fly Fishing Austin’s Shoal Creek, July 24, 2011. Online at https://www.matthewbey.com/adventures-fly-fishing-austins-shoal-creek/

- ↑ Eric Feldkamp, Filth and Fish on Shoal Creek, April 5, 2012. Online at http://diefische.org/filth-and-fish-on-shoal-creek/

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 City of Austin, Watershed Protection Department, North Urban Watersheds, Shoal Creek | Waller Creek | Johnson Creek | Lady Bird Lake, Watershed Profile - December 27, 2016. Online at (https://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Watershed/MasterPlan/WatershedProfiles_NorthUrban.pdf

- ↑ Chuck Lesniak, Environmental Officer, Watershed Protection Department, The City of Austin, State of Our Environment: Report, City of Austin, 2015. Online at http://www.austintexas.gov/watershed_protection/publications/document.cfm?id=230086

- ↑ Shoal Creek Conservancy, Shoal Creek Bird List: April 2014, 2014. Online at https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/shoal-creek-bird-list-april-2014

- 1 2 Lower Shoal Creek and New Central Library Task Force, "Lower Shoal Creek and New Central Library Planning and Design Coordination, City of Austin, January 19, 2010. Online at ftp://ftp.ci.austin.tx.us/Lower_Shoal_Creek/Shoal%20Creek%20-%20Library%20Task%20Force%20Report-Final%20Draft.pdf

- ↑ Staff, “Thunderstorms also wreaked havoc on Memorial Day 1981” Austin American-Statesman, May 25, 2015. Online at https://www.mystatesman.com/weather/thunderstorms-also-wreaked-havoc-memorial-day-1981/8F88HgOJB1nHhvTVbeR9dM/

- 1 2 3 Taylor Goldenstein, American-Statesman Staff, "Landslide along Shoal Creek leaves homeowners facing uncertainty." Austin American-Statesman, May 9, 2018. Online at https://www.mystatesman.com/news/local/landslide-along-shoal-creek-leaves-homeowners-facing-uncertainty/PHQmc0oB6JErIj1XZUlnwJ/

- ↑ City of Austin, Shoal Creek Restoration Completion Celebration, April 10, 2018. Online at http://www.austintexas.gov/blog/shoal-creek-restoration-completion-celebration

- ↑ Yoojin Cho, KXAN News, "Austin could spend $8-16M to fix Shoal Creek landslide", April 16, 2019. Online at https://www.kxan.com/news/local/austin/austin-could-spend-8-16m-to-fix-shoal-creek-landslide/1931389056

- ↑ Yoojin Cho, KXAN News, "Shoal Creek landslide area damaged even more after this week's rain", May 9, 2019. Online at https://www.kxan.com/news/local/austin/shoal-creek-landslide-area-damaged-even-more-after-this-week-s-rain/1992900924

- ↑ Matthew Prendergast, KXAN News, "Austin man found dead in Lady Bird lake identified after being swept away in flood", May 17, 2019. Online at https://www.kxan.com/news/local/austin/austin-man-found-dead-in-lady-bird-lake-identified-after-being-swept-away-in-flood/2009309124

- ↑ Tulsi Kamath, KXAN News, "Group in charge of Shoal Creek landslide repairs asks for $7.5M more from Austin city", Jun 12, 2019. Online at https://www.kxan.com/news/local/austin/group-in-charge-of-shoal-creek-landslide-repairs-asks-for-75m-more-from-austin-city/2071532707

- ↑ KXAN Staff, KXAN News, "Austin no longer plans to stabilize Shoal Creek slope from landslides", Jan 17, 2020. Online at https://www.kxan.com/news/local/austin/city-outlines-construction-projects-to-fix-shoal-creek-trail-after-landslide-2-years-ago/

- ↑ Rudy Koski, Fox 7 Austin, "New plan for 2018 slope failure on Shoal Creek reroutes, not rebuilds", January 12, 2022. Online at https://www.fox7austin.com/news/new-plan-for-2018-slope-failure-on-shoal-creek-reroutes-not-rebuilds

- ↑ City of Austin, Parks and Recreation Department, Great Northern Detention Basin Off Leash Dog Area: 6916 Great Northern Blvd. 78757, undated. Online at https://www.austintexas.gov/sites/default/files/files/Parks/GIS/Great_Northern_Detention_Basin_OLA_Kiosk.pdf

- ↑ Freese and Nichols, Great Northern Dam, undated. Online at https://www.freese.com/our-work/great-northern-dam

- ↑ George C. Werner, International-Great Northern Railroad, Texas State Historical Association, Handbook of Texas online, June 15, 2010. Modified on April 10, 2017. Online at https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/eqi04

- ↑ The Historical Marker Database, Old Quarry Site, 2016. Online at https://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=95577

- ↑ Elizabeth Findell, “Waller Creek Tunnel wasn’t built right, won’t function fully, city says”. Austin American-Statesman, March 07, 2018, online at https://www.mystatesman.com/news/local/waller-creek-tunnel-wasn-built-right-won-function-fully-city-says/iCEkGlGobGwP9bd4v5zh9N/

- ↑ JJ Velasquez, "How The Grove at Shoal Creek could impact Austin’s 2,200 acres of unzoned land". Community Impact Newspaper, Nov. 22, 2016. Online at https://communityimpact.com/austin/city-county/2016/11/22/why-the-grove-at-shoal-creek-could-have-an-impact-on-austins-2200-acres-of-unzoned-land/

- ↑ The Grove: Location: Site Plan, 2018 online at https://thegroveatx.com/site-plan/

- ↑ City of Austin, SECOND/THIRD READING SUMMARY SHEET, SECOND/THIRD READING SUMMARY SHEET, ZONING CASE NUMBER: C814-2015-0074 (The Grove at Shoal Creek Planned Unit Development), 2016. With attached memoranda and exhibits. Online at http://www.austintexas.gov/edims/document.cfm?id=266484

- ↑ ATXfloods, 2018. https://www.atxfloods.com/cameras

- ↑ Mose Buchele, New Flood Cameras Going Live At Low-Water Crossings In Austin, KUT 90.5, June 29, 2018. Online at http://kut.org/post/new-flood-cameras-going-live-low-water-crossings-austin

- ↑ City of Austin, Watershed Protection Department, Shoal Creek Flood Risk Reduction, updated April 2018. online at http://www.austintexas.gov/shoalcreekfloods

- ↑ Shoal Creek Conservancy, “Food Grease Spill in Shoal Creek Investigated” Shoal Creek Conservancy, December 19, 2016, online at https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/food-grease-spill-in-shoal-creek-december-12/

- ↑ Kevin Schwaller, "City investigates possible pollution in Shoal Creek," KXAN, Feb 15, 2016. Online at https://www.kxan.com/news/city-investigates-possible-pollution-in-shoal-creek/1049709407

- ↑ Kevin Schwaller, "Construction company charged with pollution in downtown Austin". KXAN, Jun 03, 2016. Online at https://www.kxan.com/news/construction-company-charged-with-pollution-in-downtown-austin/1049750228

- ↑ City of Austin, Watershed Protection Department, Shoal Creek Restoration: 15th-28th Streets, online at http://www.austintexas.gov/shoalcreekrestoration

- ↑ Sophia Beausoleil, "Rain caused delay in Shoal Creek Restoration; completion expected by summer," KXANMar 07, 2016. Online at https://www.kxan.com/weather/weather-news/rain-caused-delay-in-shoal-creek-restoration-should-be-finished-by-summer/1049818210

- 1 2 Austin American-Statesman, Janet Long Fish, Obituary, 2008. online at https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/statesman/obituary.aspx?n=janet-long-fish&pid=107966360&fhid=5106

- ↑ Shoal Creek Conservancy, Transforming Austin’s Oldest Hike-and-Bike Trail, [2018] online at https://shoalcreekconservancy.org/trailplan/

- ↑ Rebeca Trejo, Austin group plans to extend Shoal Creek Trail north of U.S. Highway 183, KVUE (ABC) Austin, July 3, 2018. Online at https://www.kvue.com/article/news/local/austin-group-plans-to-extend-shoal-creek-trail-north-of-us-highway-183/269-570439347

- ↑ Austin Public Library, Central Library, 2017. Online at http://austinlibrary.com/downloads/central_map_oct2017.pdf

- ↑ "The Shoal Creek Trail". Shoal Creek Conservancy. Retrieved 2023-09-07.

- ↑ "Pease Park Conservancy". Pease Park Conservancy. 2023-09-05. Retrieved 2023-09-07.