Shūmei Ōkawa | |

|---|---|

大川 周明 | |

Shūmei Ōkawa, c. 1936 | |

| Born | 6 December 1886 Sakata, Yamagata, Japan |

| Died | 24 December 1957 (aged 71) Tokyo, Japan |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Education | Tokyo Imperial University, 1911, Ph.D. 1926 |

| Occupation(s) | Educator, political philosopher, Islamic scholar, historian |

| Employers |

|

| Known for |

|

| Criminal charges |

|

| Parent | Shūkei Ōkawa (d. 1914) |

| Notes | |

Shūmei Ōkawa (大川 周明, Ōkawa Shūmei, 6 December 1886 – 24 December 1957) was a Japanese nationalist and Pan-Asianist writer, known for his publications on Japanese history, philosophy of religion, Indian philosophy, and colonialism.

Background

Ōkawa was born in Sakata, Yamagata, Japan in 1886. He graduated from Tokyo Imperial University in 1911, where he had studied Vedic literature and classical Indian philosophy. After graduation, Ōkawa worked for the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff doing translation work. He had a sound knowledge of German, French, English, Sanskrit and Pali.[3]

He briefly flirted with socialism in his college years, but in the summer of 1913 he read a copy of Sir Henry Cotton's New India, or India in transition (1886, revised 1905) which dealt with the contemporary political situation. After reading this book, Ōkawa abandoned "complete cosmopolitanism" (sekaijin) for Pan-Asianism. Later that year articles by Anagarika Dharmapala and Maulavi Barkatullah appeared in the magazine Michi, published by Dōkai, a religious organization in which Ōkawa was later to play a prominent part. While he studied, he briefly housed the Indian independence leader Rash Behari Bose.

After years of study of foreign philosophies, he became increasingly convinced that the solution to Japan's pressing social and political problems lay in an alliance with Asian independence movements, a revival of pre-modern Japanese philosophy, and a renewed emphasis on the kokutai principles.[4]

In 1918, Ōkawa went to work for the South Manchurian Railway Company, under its East Asian Research Bureau. Together with Ikki Kita he founded the nationalist discussion group and political club Yūzonsha. In the 1920s, he became an instructor of history and colonial policy at Takushoku University, where he was also active in the creation of anti-capitalist and nationalist student groups.[5] Meanwhile, he introduced Rudolf Steiner's theory of social threefolding to Japan. He developed a friendship with Aikido founder Morihei Ueshiba during this time period.

In 1922, he published Fukkô Ajia no Shomondai in 1922. Ōkawa hailed the movements started by Mahatma Gandhi in India and Mustafa Kemal in Turkey as new types of Asian revival.[6]

In 1926, Ōkawa published his most influential work: Japan and the Way of the Japanese (Nihon oyobi Nihonjin no michi), which was so popular that it was reprinted 46 times by the end of World War II. Ōkawa also became involved in a number of attempted coups d'état by the Japanese military in the early 1930s, including the March Incident, for which he was sentenced to five years in prison in 1935.[7] Released after only two years, he briefly re-joined the South Manchurian Railway Company before accepting a post as a professor at Hosei University in 1939. He continued to publish numerous books and articles, helping popularize the idea that a "clash of civilizations" between the East and West was inevitable, and that Japan was destined to assume the mantle of liberator and protector of Asia against the United States and other Western nations.[8]

Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal

After World War II, the Allies prosecuted Ōkawa as a class-A war criminal.[9] Of the twenty-eight people indicted with this charge, he was the only one not a military officer or government official. The Allies described him to the press as the "Japanese Goebbels" and said he had long agitated for a war between Japan and the West. In pre-trial hearings, Ōkawa said that he had merely translated and commented on Vladimir Solovyov's geopolitical philosophy in 1924, and that in fact Pan-Asianism did not advocate for war.[10]

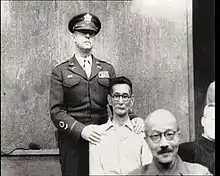

During the trial, Ōkawa behaved erratically, including dressing in pajamas, sitting barefoot, and slapping the head of former prime minister Hideki Tōjō while shouting in German "Inder! Kommen Sie!" (Come, Indian!). Ōkawa maintained since the beginning of the trial that the court was a farce and not even worthy of being called a legal court. He also at one point shouted "This is act one of the comedy!". U.S. Army psychiatrist Daniel Jaffe examined him and reported that he was unfit to stand trial. The presiding judge Sir William Webb concluded that he was mentally ill and dropped the case against him. Some thought he was feigning madness.[11] Of the remaining defendants, seven were hanged and the rest imprisoned.[12][11]

After the war

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Japan |

|---|

|

Ōkawa was transferred from jail to a US Army hospital in Japan, which confirmed his mental illness caused by syphilis. Later, he was transferred to Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital, a mental hospital, where he completed the third Japanese translation of the entire Quran.[13] He was released from hospital in 1948, shortly after the end of the trial. He spent the final years of his life writing a memoir, Anraku no Mon, reflecting on how he found peace in the mental hospital.

In October 1957, Prime Minister of India Jawaharlal Nehru requested an audience with him during a brief visit to Japan. The invitation was hand-delivered to Ōkawa's house by an Indian Embassy official, who found that Ōkawa was already on his deathbed and was unable to leave the house. He died on 24 December 1957.[14]

Major publications

- Some issues in re-emerging Asia (復興亜細亜の諸問題), 1922

- A study of the Japanese spirit (日本精神研究), 1924

- A study of chartered colonisation companies (特許植民会社制度研究), 1927

- National History (国史読本), 1931

- 2600 years of the Japanese history (日本二千六百年史), 1939

- History of Anglo-American Aggression in East Asia (米英東亜侵略史), 1941

- Best-seller in Japan during WW2

- Introduction to Islam (回教概論), 1942

- Quran (Japanese translation), 1950

Notes

- ↑ "Okawa Shumei". Merriam Webster's Biographical Dictionary (fee, via Fairfax County Public Library). Springfield, MA: Gale. Merriam-Webster. 1995. GALE|K1681157864. Retrieved 20 January 2014. Biography in Context.

- ↑ Yoshimi, Takeuchi, Profile of Asian Minded Man x: Okawa Shumei (PDF), archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007, retrieved 20 January 2014

- ↑ Wakabayashi, Modern Japanese Thought, p. 226

- ↑ Samuels, Securing Japan: Tokyo's Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia, p. 18

- ↑ Calvocoressi, The Penguin History of the Second World War p. 657

- ↑ Aydin, C. (2007). The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought. Columbia studies in international and global history. Columbia University Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-231-13778-2. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- ↑ Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan, p. 572

- ↑ Wakabayashi, Modern Japanese Thought, pp. 226–227

- ↑ 15 March 1946 Tavenner Papers & IMTFE Official Records Files on Defendants; Okawa, Oshima 1946 University of Virginia Law Library

- ↑ Japan’s Pan-Asianism and the Legitimacy of Imperial World Order, 1931–1945

- 1 2 Halzack, Sarah (17 January 2014). "A Curious Madness: An American Combat Psychiatrist, a Japanese War Crimes Suspect, and an Unsolved Mystery from World War II". The Washington Post. p. B7. Retrieved 30 January 2014. (review of book by Eric Jaffe)

- ↑ Maga, Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials

- ↑ While Ōkawa made reference to the Arabic original, he made his translation from about ten language editions, including English, Chinese, German, and French, as his knowledge of Arabic was only basic. See Krämer, "Pan-Asianism's Religious Undercurrents," pp. 627–630.

- ↑ Sekioka Hideyuki. Ōkawa Shūmei no Dai-Ajia-Shugi. Tokyo: Kodansha, 2007. p. 203.

References

- Calvocoressi, Peter; Wint, Guy; Pritchard, R John (1999). The Penguin History of the Second World War. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-028502-4.

- Jaffe, Eric (2014). A curious madness : an American combat psychiatrist, a Japanese war crimes suspect, and an unsolved mystery from World War II (First Scribner hardcover ed.). New York: Scribner. ISBN 9781451612059. LCCN 2013040208. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

eric jaffe.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The Making of Modern Japan. Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-00991-6.

- Krämer, Hans Martin (August 2014). "Pan-Asianism's Religious Undercurrents: The Reception of Islam and Translation of the Qur'ān in Twentieth-Century Japan". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 73 (3): 619–640. doi:10.1017/S0021911814000989. S2CID 55349358.

- Maga, Timothy P. (2001). Judgment at Tokyo: The Japanese War Crimes Trials. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-2177-9.

- Samuels, Richard J (2007). Securing Japan: Tokyo's Grand Strategy and the Future of East Asia. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4612-2.

- Wakabayashi, Bob (2007). Modern Japanese Thought. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-4612-2.

Further reading

- Esenbel, Selçuk (October 2004). "Japan's Global Claim to Asia and the World of Islam: Transnational Nationalism and World Power, 1900–1945". The American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 109 (4). Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 20 January 2014.

- Szpilman, Christopher W. A. "The Dream of One Asia: Okawa Shumei and Japanese Asianism". In Fuess, Harald (ed.). The Japanese Empire in East Asia. pp. 49–64.

External links

- Ōkawa hitting Tojo illustration