| Siege of the Alcázar | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish Civil War | |||||||

Alcázar of Toledo in 2006 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~8,000 | 1,028 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| High |

48–65 dead 438 wounded 22 missing | ||||||

The siege of the Alcázar was a highly symbolic Nationalist victory in Toledo in the opening stages of the Spanish Civil War. The Alcázar of Toledo was held by a variety of military forces in favour of the Nationalist uprising. Militias of the parties in the Popular Front began their siege on July 21, 1936. The siege ended on September 27 with the arrival of the Army of Africa under Francisco Franco.

Background

On July 17, 1936, Francisco Franco began the military rebellion in Spanish Morocco. On July 18, the military governor of the province of Toledo, Colonel Moscardó, ordered the Guardia Civil of the province to concentrate in the city of Toledo. During July 19 and 20, various attempts were made by the War Ministry of the Republican government to obtain the munitions in the arms factory at Toledo. Each time, Colonel Moscardó refused and was threatened that a force from Madrid would be sent against him.

Forces

The Republican forces dispatched to Toledo consisted of approximately 8,000 men of the militias of the FAI, CNT and the UGT. They had several pieces of artillery, a few armoured cars, and two or three tankettes. The Republican Air Force performed reconnaissance, spotted for the artillery and bombed the Alcázar on 35 occasions.

Participants in the Nationalist uprising were the 800[2] men of the Guardia Civil, 6 cadets[3] of the Military Academy, one hundred Army officials and 200 civilians from right-wing political parties.[3] The only weapons that they possessed were rifles, a few old machine guns and some hand grenades, but the officials and Guardia Civil had managed to bring in abundant ammunition.

Approximately 670 civilians (five hundred women and 50 children)[4] lived in the Alcázar for the duration of the siege. Many of these were the family members of the Guardia Civil while others had fled from the advancing Republican militias. The women were given no role in the defence of the Alcázar; they were not even allowed to cook or nurse the wounded. However, their presence in the Alcázar provided the men with the moral courage to continue the defence. The civilians were kept safe from Republican attacks, the five civilians that died were due to natural causes. There were two births during the siege. One of the babies born, who eventually became an officer in the Spanish military, was expelled from the Army in the late 1970s for joining the UMD.

Additionally, ten prisoners captured during sorties in Toledo and about 100[5]-200[6] hostages (including women and children) were held by the Nationalists through the duration of the siege. Among the hostages were the Civil Governor of the province and his family.[3] Two babies were born during the siege.[7] Some sources say the hostages were never heard from again after the siege,[8] though one journalist who visited the fortress after the battle reported seeing the hostages chained to a railing in the cellar.[9]

Symbolism

The Alcázar became the residence of the Spanish monarchs after the reconquest of Toledo from the Moors but was abandoned by Philip II and in the 18th century was converted into a military academy. After a fire in 1886, parts of the Álcazar had been reinforced with steel and concrete beams.

The Nationalists saw the Alcázar as a representation of the strength and dominance of Spain. Losing the Alcázar to the Republicans would have been a serious blow to the Nationalists' vision and morale. Toledo was also the spiritual capital of the Spanish Visigothic Kingdom.

Apart from a small-arms factory, Toledo was a city of no military value to either side; the Nationalist forces there were small, isolated, badly equipped and in no condition to conduct offensive operations. The Republican government believed that since the garrison was only 64 kilometres (40 mi) southwest of Madrid and would not be receiving any immediate help from the other Nationalist forces, it would be an easy propaganda victory.

Siege

July 21

A proclamation declaring a "State of War" was read by Captain Emilio Vela-Hidalgo, Captain of Cavalry (and nephew of the Republican General Manuel Cardenal Dominicis,[10] at the Military Academy at 7 a.m. in the Zocodover, the main plaza of Toledo. Euphemistic orders were given for "the arrest of well-known left-wing activists" in Toledo, but only the governor of the local prison was arrested.

The Republican troops sent from Madrid first arrived at the Hospital of Tavera on the outskirts of Toledo but redirected their attack towards the Arms Factory upon receiving heavy fire from the hospital. A detachment of 200 Guardia Civil was stationed at the Arms Factory and negotiations with the Republicans ensued. During these talks, the Guardia Civil loaded trucks with ammunition from the factory and sent it to the Alcázar before evacuating and destroying the factory.

July 22 – August 13

By July 22, the Republicans controlled most of Toledo and sought the surrender of the Alcázar by artillery bombardment. For the duration of the siege, the Nationalists engaged in a passive defence, only returning fire when an attack was imminent.

Colonel Moscardó was called on the telephone by the chief of the Worker's Militia, Commissar Cándido Cabello, on the morning of July 23 in Toledo and told that if the Alcázar were not surrendered within ten minutes, Moscardó's 24-year-old son, Luis, who had been captured earlier in the day, would be executed. Colonel Moscardó asked to speak to his son and his son asked what he should do. "Commend your soul to God," he told his son, "and die like a patriot, shouting,'¡Viva Cristo Rey!' and '¡Viva España!' The Alcázar does not surrender." "That," answered his son, "I can do." Luis was immediately shot, contrary to the rumour that he was not in fact shot until a month later "in reprisal for an air raid".[11]

August 14 – September 17

On August 14, the Republicans changed tactics after they felt the defences on the northern side of the Alcázar had been sufficiently reduced. Over the next five weeks, the Republicans attacked the House of the Military Government on eleven occasions but were turned back each time by the Nationalists. After the war, Franco posthumously awarded Guillermo Juárez de María y Esperanza, with the Orden del Mérito Militar for his bravery in the breach. Had the Republicans captured the House of the Military Government, it would have enabled them to mass a large number of troops only 37 metres (40 yd) away from the Alcázar.

An envoy from the Republicans, Major Rojo, was sent to Colonel Moscardó on September 9 to ask for the surrender of the Alcázar. This was refused, but Colonel Moscardó requested for a priest to be sent to baptize the two children born during the siege and to also say Mass.

Vázquez Camarassa, a Madrid preacher with left-wing views, was sent to the Alcázar during the morning of September 11, performed the necessary functions and issued a general absolution to the defenders of the Alcázar. That evening, Major Rojo met with Colonel Moscardó to discuss the evacuation of the women and children. The women unanimously replied that they would never surrender and if need be would take up arms for the defence of the Alcázar.[12]

The Chilean Ambassador to Spain, José Ramón Gutiérrez, having heard that the previous attempts for surrender failed, went on September 12 to secure the surrender of the Alcázar. He was unable to contact Colonel Moscardó because the telephone wires had been damaged the previous night from grenades thrown by the Republican militias and he was unwilling to use other methods of communication.

September 18

From August 16 the Republicans had been digging two mines towards the southwest tower of the Alcázar. On the morning of September 18, explosives in the mines were detonated by Francisco Largo Caballero,[13] completely destroying the southwest tower and the two defenders in it. Approximately 10 minutes after the explosion, the Republicans launched four attacks on the Alcázar with the aid of armoured cars and tanks. The attacks failed after a determined defence by the Nationalists, but the Republicans responded with a continuous artillery bombardment of the Alcázar throughout the night and into the next day.

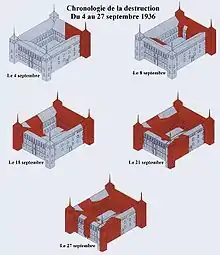

September 19–26

The bombardment of the outlying buildings had been so great that communication between them and the Alcázar had become impossible. A withdrawal from the buildings was ordered and by the night of September 21, the garrisons were concentrated in what remained of the Alcázar. The Republicans attacked the outlying buildings on the morning of September 22, but progress was slow because they did not realize that the buildings had been abandoned.

At 5 a.m. on September 23, the Republicans assaulted the northern breaches of the Alcázar and surprised the defenders by lobbing grenades and dynamite. The Nationalists on that side were driven into the courtyard of the Alcázar, but reserves arrived from elsewhere in the building to drive back the attack.

A fresh assault was mounted later in the morning, this time led by a tank. Wave after wave of Republican soldiers attacked the breaches, but after 45 minutes the attack had ground to a halt and fell back.

Relief

The first sign of an advancing Nationalist column was on August 22 when a plane sent by Franco airlifted a trunk of food into the Alcázar along with a message to the defenders that the Army of Africa was on its way to relieve the garrison. By September 26, the Nationalist columns had reached the village of Bargas, four miles (6 km) north of Toledo.

The position of the Republicans in Toledo grew desperate and on the morning of September 27, they made a final assault on the Alcázar. The attack was repulsed and shortly after the Nationalists moved from Bargas to end the siege. After the arrival of the main Nationalist force, most of the Republican troops fell back in disorder on Aranjuez.

Aftermath

The symbolic value of the Alcázar grew as weeks went by, and the Republicans threw badly needed men, artillery and weapons into the fortress capture (instead of using them to confront Franco's northern advance through western Spain). The press was invited by the Republican government to witness the explosion of the mines and storming of the Alcázar on September 18, when the Prime minister Francisco Largo Caballero himself detonated the mine, but it would not be until September 29 that the press entered the Alcázar, this time by the invitation of the Nationalists, turning the whole affair into a huge propaganda victory for the Nationalists, undermining the Republican morale.

Franco's decision to relieve the defenders of the Alcázar was a controversial one at the time. Many of his advisers thought that he should have kept up the advance towards Madrid because the besiegers of the Alcázar would have been recalled to Madrid for its defense. However, Franco believed that the propaganda value of the Alcázar was more important and ordered the Army of Africa to relieve it. Indeed, when Franco arrived at the Alcázar one day after its relief, he was greeted by Moscardó, who said: "No further news in the Alcázar, my General. I give it to you destroyed, but with its honour preserved". Two days after the relief of the Alcázar, Franco was proclaimed Generalisimo and in October was declared the head of state.

The story of the siege was very interesting for foreign supporters of Franco, who would read the several books published in foreign languages, and would strive for meeting Moscardó when visiting wartime Spain. In December 1936 a delegation of Romanian Iron Guard led by Ion Moța and Vasile Marin presented a ceremonial sword to the survivors of the siege and announced the alliance of their movement with the Spanish Nationalists.[1]

In popular culture

The siege was the basis for the prize-winning 1940 Italian war film, L'assedio dell'Alcazar, directed by Augusto Genina. In Spanish, the film is known as Sin novedad en el Alcázar.

See also

- List of Spanish Nationalist military equipment of the Spanish Civil War

- List of Spanish Republican military equipment of the Spanish Civil War

- El Alcázar, a Spanish newspaper targeting the búnker, the hardline supporters of Francoism even after Franco's death.

- Fifth Regiment

- The closing section of The Dangerous Years by Gilbert Frankau, in which one of the characters and his wife are caught up in the siege.

References

General

- Eby, Cecil D. The Siege of the Alcazar. New York: Random House, 1965.

- McNeill-Moss, Geoffrey. The Siege of the Alcázar: A History of the Siege of the Toledo Alcázar, 1936. London: Rich & Cowan; New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1937. ISBN 1-164-50712-5. Moss arrived in Toledo three weeks after the end of the siege and stayed for three months, interviewing survivors and checking reports by Moscardó and the internal newspaper. It was re-published and translated several times. While Moss admires the defenders, he is careful in distinguishing his conjectures from oral reports.[14]

- Thomas, Hugh. The Spanish Civil War. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1961. ISBN 0-375-75515-2

- Boletin de GEFREMA - Grupo de estudios del Frente de Madrid no.14 November 2008

Notes

- 1 2 Quesada, Alejandro (2014). The Spanish Civil War 1936–39. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-78200-782-1.

- ↑ Luchando por Franco: Voluntarios europeos al servicio de la España fascista, 1936–1939, page 61, Judith Keene, Salvat, 2002, ISBN 84-345-6893-4. Original English title: Fighting for Franco.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, Hugh. (2001). The Spanish Civil War. Penguin Books. London. p.236

- ↑ Luchando por Franco, page 62.

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. (2006). The Battle for Spain. The Spanish Civil War, 1936–1939. Penguin Books. London. p.122

- ↑ Preston, Paul. (2006). The Spanish Civil War. Reaction, revolution & revenge. Harper Perennial. London. p.128

- ↑ Krüger, Christine G., and Sonja Levsen, eds. War volunteering in modern times: from the French Revolution to the Second World War. Springer, 2010, p.215

- ↑ Beevor, Antony. The Battle for Spain: The Spanish Civil War 1936-1939. Hachette UK, 2012, p.122

- ↑ Eby, Cecil D. The Siege of the Alcazar. Random House, 1965, p.187

- ↑ Boletin de GEFREMA - Grupo de estudios del Frente de Madrid no.14 November 2008

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. (2021). Great Sieges in World History: From Ancient Times to the 21st Century. ABC-CLIO. p. 215. ISBN 978-1-4408-6803-0.

- ↑ Moss, p203

- ↑ Moss, p217

- ↑ Evaluation of Moss's book in Luchando por Franco, page 73