| Siege of Chartres | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the French Wars of Religion | |||||||

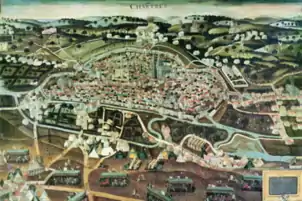

Image by Jean Perrissin and Jacques Tortorel of the siege in progress, the breach visible in the front | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Royalists | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Nicolas des Essars, Sieur de Linieres | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Probably 9,000[1] | Some 6,000 (plus townspeople)[1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 300 to 400 | 250 | ||||||

The siege of Chartres (28 February – 15 March 1568) was a key event of the second French Wars of Religion. The siege saw the Huguenot forces fail to take the heavily defended town, ultimately concluding the second civil war in a negotiated settlement a week later. One of the very few engagements in the second civil war, the siege was led by Louis, Prince of Condé, fresh off regrouping after his defeat at the Battle of Saint-Denis. The defensive efforts were run by the military governor of Chartres, Nicolas des Essars, Sieur de Linières.

Town of Chartres

The town of Chartres was a prosperous city, situated in one of France's richest agriculture centres, making it a tantalising prize for the Huguenot forces to besiege.[2] The town sat on an important artery, between Paris and the towns of the south and west which had made it a busy thoroughfare for troops during the civil war so far, with columns heading through in October and then again in December.[3] A variety of professions laboured in the town, from craftspeople, to professional administrators with a population of around 8000.[2] As befitted a place of its size the town was host to a Cathedral.[4] In peacetime it was defended by six militia companies each composed of 100 of the town's bourgeois.[5][6]

Prelude to siege

Protestants

In the wake of their decisive defeat at Saint-Denis the Protestants moved south to near Melun where they could be confident their rear was protected by the city of Orléans which they had seized at the start of the civil war.[7] The forces of the crown pursued them, no longer under the command of the late constable but rather Henry Duke of Anjou.[8][9] The royal army marched first to Nemours from where it pursued the Huguenots across Champagne, missing an opportunity to bring the weakened force to battle near Notre-Dame de l'Épine.[7] As such the Huguenots were able to temporarily vacate France.[7] Linking up with a force of German mercenaries they had hired, they increased their formerly shattered strength, allowing them to re-enter France.[9] The crown forces did not immediately pursue the returning Huguenots, confident that the Huguenot army would simply break apart over the winter months.[7] The crown felt that given the lack of ability of the Huguenot leadership to pay wages to their troops, avoiding battle until the Huguenots collapsed would be the easiest strategy.[7] However, Condé and Gaspard II de Coligny were able to hold the army together through early 1568, marching back to Orléans and linking up with yet more troops that had arrived from the south of France.[9] These southern troops had relieved Orléans from a weak siege, and taken the surrender of Blois and Beaugency in their absence.[9][7]

Now greatly strengthened, and facing a royal army that clearly had little desire to fight, tucked away in Paris, Condé decided to strike at the centre of the Catholic cause, with the side benefit of offering a rich target to his unpaid men.[7] In late February, they reached Chartres, and while part of the army guarded the road to Paris in case of any forays to relieve the town from the main royal army, around 9000 men prepared to invest Chartres.[7]

Chartres

The city of Chartres, had been subject to an eventful few months, after the outbreak of the civil war in September 1567.[10] On 29 September, de Gallot, leader of a cavalry company in Chartres was named the military governor of the town, being the leader of the only regular troops present in the town.[6] After word of the fall of Orléans reached the town, the échevins, conscious of the towns vulnerability in light of this, petitioned the crown to raise several companies of troops for the cities protection.[6] The crown granted this request on 17 October, licensing the raising of four companies of 300 under the command of Fontaine-la-Guyon.[6] Tensions immediately arose between the échevins and the governor, as the échevins desired the companies be reduced in size to 200 per company, given the town was to be paying for them.[11] The crown granted this reduction in size on 24 October and the companies had mustered by 26 October.[11]

After the threat to Chartres dissipated in December, with the Huguenot forces being pursued away through Champagne, the échevins petitioned to disband two of the four companies.[3] The governor protested this, complaining that the town was interfering in his military affairs. But, after admonishing both sides, the crown granted the reduction, and then a further reduction to only one company in early January as Condé exited France.[3][12]

With Condé now marching towards Orléans, Anjou began making plans to defend Chartres, regiments stationed elsewhere under Jehan de Monluc and the count of Cerny were ordered to head to Chartres, On 12 February 1568, Linières and his gendarme company accompanied by an engineer were ordered to head to Chartres, with Linières to replace Fontaine-la-Guyon's command.[13] He arrived on 24 February.[13] Also on 12 February de Monluc departed his command, having got word his father was ill, leaving his troops in the command of d'Ardelay.[14] The troops Monluc left had become quite rowdy, and were terrorising the countryside, due to their pay being in arrears.[14] The town refused to allow them entry, fearful of what they might do, chasing them away with warning shots.[14] Yet the crown would not relent, having got word of an artillery train in the Huguenot camp, ordering the town to admit them on 22 February. They did after making d'Ardelay swear an oath to respect the town's bourgeois.[14]

On 26 February the troops under Cerny arrived, making it just in time before the Huguenot forces were able to seal off the city.[2] In total there were now more than 4000 troops in the city, forming 25 companies.[2]

Siege

Linières and the échevins conducted a survey of the town's defences, correcting perceived deficits in the strength of the walls, and supplementing them with the creation of inner works and a hospital.[15] A signalling system was further established on the tower of the city's cathedral.[15] The town's own paramilitary forces, the six companies of bourgeois, were integrated into the town's defences, assigned places on the walls.[15] Pioneers were also mobilised from among the regular citizens of the town, and those who had fled into the walls of the city, from the surrounding area.[15] This gave a total defensive force of around 6000 for Linières to rely on, though with much of it drawn from the civilian town population.[16] This totalled 2 defenders per metre of wall around the towns circuit, and ⅔ of the total besieging forces.[16]

Multiple sorties were engaged in from the town as the besiegers began to set up their attacking positions.[16] On 2 March Condé established his batteries choosing a hill overlooking the north and the Drouaise gate.[16] This decision has been roundly criticised by military commentators, who noted that although this choice gave the cannons excellent vantage over the walls, it was against the strongest walls of the town that they were faced, while elsewhere far weaker spots were available.[16] After a few days of suppressive fire from this position he ordered a full bombardment to begin on 5 March at the gate and the wall to the east of it.[16] On 7 March a section of the wall by the gate collapsed, and the Huguenot forces rushed forth, to try and take advantage of the breach, however the royal forces inside were able to successfully repulse these attempts.[16] Whilst the Huguenots were assaulting the breach, a diversionary attack on the other side of the city cost d'Ardelay his life after he was shot in the head.[4] The cannons returned to work the next day in an attempt to enlarge the breach they had made, yet the civilian defenders had already built containment fortifications inside the walls behind the breach, and had placed a cannon of their own called la Huguenot to watch over the gap in the wall.[16] As such when the Huguenot forces attempted again to assault the breach they were blown back by iron shot from the cannon.[16]

After a reconnaissance mission to assess the breach, Condé at last concluded that it was unassailable, and that he would be better served by moving his cannons to other positions. However by this time truce negotiations were already in progress, and a truce was declared on 13 March.[16]

Aftermath

Casualties

In total around 300-400 Huguenot soldiers had died during the siege, whilst for the defenders the total fatalities were around 250 soldiers with 500 wounded among the royal forces present in the city.[17] Civilian casualties are unknown.[17] Anjou ordered that the two highest profile casualties among the royal forces, that of d'Ardelay and de Chaulx, who was the cavalry lieutenant under Linières, be given expensive funerals by the town. The funerals were both granted, and the remains were interred in the city's cathedral.[4] This did not sit well with the city's cathedral chapter, who protested that it was forbidden that anyone be interred in the holy place reserved for the Virgin. Both Anjou and Charles IX insisted however, and so it was done.[4] Shortly thereafter they were disinterred and moved to a different church during the night.[4]

Cost

The city calculated that the cost they paid for supporting the royal army, and all the defensive expenditures required for the siege totalled around 87,801 livres. This total is excluding damage to private residences and communities outside the walls of Chartres that may have been laid waste to.[17] The majority of this cost was tied up in wages and food for the troops, with only a limited amount of it in expenditure for wall repairs and fortifications.[18]

Further expenditure came to the town in the wake of the siege, with 882 livres spent to make 31 gold medallions to honour the service of those who had played a particularly significant role in winning the siege, with Linières and Pelloy, the royal engineer, receiving theirs on golden chains, while the rest were given ribbons to hold them up.[19] The commanders of the two original companies raised in October were granted a single livre each in recompense, the equivalent of several days wages for their position.[19] Pelloy was also granted a cash reward for his service of 780 livres, whilst Cerny was compensated for the loss of his horse during the battle. Linières' second in command Rancé was given the equivalent of two weeks pay.[19]

The town

Whilst the town was grateful for the defence they had received from the royal troops, once the danger had passed and peace was declared, the échevins were keen to get rid of them as soon as possible, so as to not have to pay for hosting them for any longer than required.[4] They petitioned the king for their removal, and raised a loan so they could pay them off to leave as quickly as possible.[4] Having loaned Linières and his troops 450 livres so that they might depart, the town was left with a problem when, after war resumed in late 1568, Linières was killed at the Battle of Jarnac.[4]

Wider context

Ultimately the Peace of Longjumeau established on 24 March 1568 between the crown and the rebels would prove little more than a temporary truce. Neither side particularly happy with it and the conflict resumed a few months later.[20] That war would in turn be concluded by the Peace of Saint-Germain-en-Laye which aimed to be a more final peace for the French wars of religion, though this ambition did not materialise.[21]

See also

References

- 1 2 Wood, James B. (2002). The King's Army. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 0-521-52513-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 215. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 0521525136.

- ↑ Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 4 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 209. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 208. ISBN 0521525136.

- ↑ Holt, Mack (2011). The French Wars of Religion 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780521547505.

- 1 2 3 4 Salmon, J.H.M (1975). Society in Crisis: France in the Sixteenth Century. Metheun & Co. p. 172. ISBN 0416730507.

- ↑ Baird, Henry (1880). History of the Rise of the Huguenots In Two Volumes: Vol 2 of 2. Hodder & Stoughton. p. 205.

- 1 2 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 211. ISBN 0521525136.

- ↑ Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 212. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 213. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 4 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 214. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 4 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 216. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 217. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 219. ISBN 0521525136.

- ↑ Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576 0521525136. Cambridge University Press. p. 221. ISBN 0521525136.

- 1 2 3 Wood, James (2002). The King's Army: Warfare, Soldiers and Society during the Wars of Religion in France, 1562-1576. Cambridge University Press. p. 223. ISBN 0521525136.

- ↑ Holt, Mack (2011). The French Wars of Religion: 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press. pp. 66–9. ISBN 9780521547505.

- ↑ Holt, Mack (2011). The French Wars of Religion: 1562-1629. Cambridge University Press. p. 71. ISBN 9780521547505.