| Siege of Merv | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Mongol conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Mongol Empire | Khwarazmian Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Dawud (governor) | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| City garrison | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Modern estimates range from 30,000 to 50,000 | 12,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Most of the garrison | ||||||

Merv Location of the siege on a map of modern Turkmenistan  Merv Merv (West and Central Asia) | |||||||

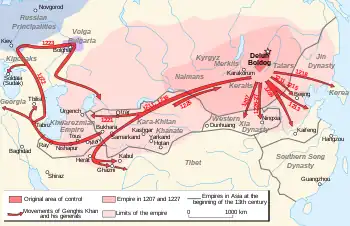

The siege of Merv (Persian: محاصره مرو) took place in April 1221, during the Mongol conquest of the Khwarazmian Empire. In 1219, Genghis Khan, ruler of the Mongol Empire, invaded the Khwarazmian Empire ruled by Shah Muhammad II. While the Shah planned to defend his major cities individually and divided his army to station in several garrisons, the Mongols laid siege to one town after another deep into Khorasan, heart of the Khwarazmian Empire.

The city of Merv was a major center of learning, trade and culture of Khorasan, then part of the extensive Khwarazmian Empire. A Mongol force, estimated to number between 30,000 and 50,000 men and led by Tolui, son of Genghis Khan, traversed the Karakum Desert after destroying the former imperial capital Gurganj in the north. According to several contemporary historians, Merv's defenders surrendered to Mongols within 7 to 10 days.

Historical accounts contend that Merv's entire population, including refugees, who had previously fled from other besieged towns of the empire, were killed. Mongols are reputed to have slaughtered 700,000 people,[1][2][3] while Persian historian, Juvayni, puts the figure at more than 1,300,000,[4] making it one of the bloodiest captures of a city in world history.

Background

Merv, also formerly known as "Alexandria", "Antiochia in Margiana" and "Marw al-Shāhijān", was a major Iranian city on the historical Silk Road, situated in Khorasan. Capital of several polities throughout its rich history, Merv became the seat of the caliph al-Ma'mun and the capital of the entire Islamic caliphate in the beginning of the 9th century.[5] In the 11th–12th centuries, Merv was the capital of the Great Seljuk Empire.[6][7][8] Around this time, Merv turned into a chief centre of Islamic science and culture, attracting as well as producing renowned poets, musicians, physicians, mathematicians and astronomers.

Great Persian polymath Omar Khayyam, among others, spent a number of years working at the observatory in Merv. As Persian geographer and traveller al-Istakhri wrote of Merv: "Of all the countries of Iran, these people were noted for their talents and education." Arab geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi counted as many as 10 giant libraries in Merv, including one within a major mosque that contained 12,000 volumes.[9] During the 12th–13th centuries, just before the Mongol conquest, Merv may have been the world's largest city, with a population of up to 500,000. During this period, Merv was known as "Marw al-Shāhijān" (Merv the Great), and frequently referred to as the "capital of the eastern Islamic world". According to geographer Yaqut al-Hamawi, the city and its structures were visible from a day's journey away.

Prelude

There are conflicting reports as to the size of the total Mongol invasion force. The highest figures were calculated by classical Muslim historians such as Juzjani and Rashid al-Din.[10][11] Modern scholars such as Morris Rossabi have indicated that the total Mongol invasion force cannot have been more than 200,000;[12] John Masson Smith gives an estimates of around 130,000.[13] The minimum figure of 75,000 is given by Carl Sverdrup, who hypothesizes that the tumen (the largest Mongol military unit) had often been overestimated in size.[14] The Mongol armies arrived in Khwarazmia in waves: first, a vanguard led by Genghis' eldest son Jochi and the general Jebe crossed the Tien Shan passes, and started laying waste to the towns of the eastern Fergana Valley. Jochi's brothers Chagatai and Ogedai then descended on Otrar and besieged it.[15] Genghis soon arrived with his youngest son Tolui, and split the invasion force into four divisions: while Chagatai and Ogedai were to remain besieging Otrar, Jochi was to head northwest in the direction of Gurganj. A minor detachment was also sent to take Khujand, but Genghis himself took Tolui and around half of the army — between 30,000 and 50,000 men — and headed westwards.[16]

The Khwarazmshah faced many problems. His empire was vast and newly formed, with a still-developing administration.[17] His mother Terken Khatun still wielded substantial power in the realm—Peter Golden termed the relationship between the Shah and his mother "an uneasy diarchy", which often acted to Muhammad's disadvantage.[18] The Shah distrusted most of his commanders, the only exception being his eldest son and heir Jalal al-Din, whose military skill had been critical at the Irghiz River skirmish the previous year.[19] If the Khwarazmshah sought open battle, as many of his commanders wished, he would have been outmatched by the Mongol army, in both the size of the army and its skill.[20] The Shah thus decided to distribute his forces as garrison troops in the empire's most important cities.[21]

Siege

The garrison at Merv was only about 12,000 men, and the city was inundated with refugees from eastern Khwarazm.

In April 1221, Tolui, son of Genghis Khan, besieged the city for six days. On the seventh day, he assaulted Merv. However, the garrison beat back the assault and launched their own counter-attack against the Mongols. The garrison force was similarly forced back into the city. The next day, the city's governor surrendered the city on Tolui's promise that the lives of the citizens would be spared. As soon as the city was handed over, however, Tolui slaughtered almost every person who surrendered, in a massacre possibly on a greater scale than that at Gurganj. Arab historian Ibn al-Athir described the event basing his report on the narrative of Merv refugees:

Genghis Khan sat on a golden throne and ordered the troops who had been seized should be brought before him. When they were in front of him, they were executed and the people looked on and wept. When it came to the common people, they separated men, women, children and possessions. It was a memorable day for shrieking and weeping and wailing. They took the wealthy people and beat them and tortured them with all sorts of cruelties in the search for wealth ... Then they set fire to the city and burned the tomb of Sultan Sanjar and dug up his grave looking for money. They said, 'These people have resisted us' so they killed them all. Then Genghis Khan ordered that the dead should be counted and there were around 700,000 corpses.[9]

A Persian historian, Juvayni, put the figure at more than 1,300,000.[4] Each individual soldier of the conquering army "was allotted the execution of three to four hundred persons," many of those soldiers being levies from Sarakhs who, because of their town's enmity toward Merv, "exceeded the ferocity of the heathen Mongols in the slaughter of their fellow-Muslims."[22] Almost the entire population of Merv, and refugees arriving from the other parts of the Khwarazmian Empire, were slaughtered, making it one of the bloodiest captures of a city in world history.[23]

Aftermath

Some time later in 1221, Khwarazmshah Jalal ad-Din attacked a detachment of Mongols near Wilan, which provoked Genghis Khan into sending an army of 30,000 troops under Shigi Qutuqu.[24] As a result of the tactics adopted by Jalal ad-Din, the Mongol army was destroyed in a two-day battle. The Khwarazmians started an insurgency after the news of Shigi Qutuqu's defeat at the battle of Parwan spread throughout the empire. Inspired by Jalal al-Din's back-to-back victories against the Mongol army, Kush Tegin Pahlawan led an insurgency in Merv and seized it successfully, followed by a successful attack on Bukhara. [25]

Excavations revealed the drastic rebuilding of the city's fortifications in the aftermath of their destruction, but the city's prosperity had passed. The Mongol invasion spelled the eclipse of Merv and other major centres for more than a century. After the Mongol conquest, Merv became part of the Ilkhanate, and it was consistently looted by Chagatai Khanate. In the early part of the 14th century, the town became the seat of a Christian archbishopric of the Eastern Church under the rule of the Kartids, vassals of the Ilkhanids. By 1380, Merv belonged to the empire of Timur (Tamerlane).

References

Citations

- ↑ Naimark, Norman (2017). Genocide A World History. Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9780199765263.

The city of Merv fell in February 1221 to Tolui, Genghis Khan's youngest son, who is said to have massacred 700,000 persons while sparing some eighty craftsmen.

- ↑ Goldstein, Joshua (2011). Winning the War on War The Decline of Armed Conflict Worldwide. Penguin Publishing Group. pp. 45–63. ISBN 9781101549087.

- ↑ Bonner, Jay (2017). Islamic Geometric Patterns Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction. Springer New York. p. 115. ISBN 9781441902177.

- 1 2 Alāʼ al-Dīn ʻAṭā Malik Juvaynī, History of the World Conqueror, J.A. Boyle, transl., pp.163-4 (Harvard Univ. Press. 1968).

- ↑ Sourdel, Dominique. "Al-Maʾmūn, Abbāsid caliph". Encyclopedia Britannica. Archived from the original on 7 June 2021. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

Al-Maʾmūn, having become caliph of the entire ʿAbbāsid empire, decided to continue to reside at Merv, assisted by his faithful Iranian vizier al-Faḍl.

- ↑ Starr, Frederick (2015). Lost Enlightenment. Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton University Press. p. 425.

Sanjar's capital at Merv was not the ancient center around the ErkKala but a ...

- ↑ Chandler, Tertius (2013). 3000 Years of Urban Growth. Elsevier Science. p. 232.

Hence under 125000 and probably under 100000—as Merv rose very fast as a Seljuk capital

- ↑ Brummel, Paul (2005). Turkmenistan. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 7.

The Seljuks were to establish a mighty empire stretching right to the Mediterranean, with Merv as its capital.

- 1 2 Tharoor, Kanishk (12 August 2016). "Lost cities #5: how the magnificent city of Merv was razed – and never recovered". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 29 April 2021. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ↑ Juzjani 1873, p. 968.

- ↑ al-Din 1998, 346.

- ↑ Rossabi 1994, pp. 49–50.

- ↑ Smith 1975, pp. 273–274, 280–284.

- ↑ Sverdrup 2010, pp. 109, 113.

- ↑ Buniyatov 2015, p. 114.

- ↑ Sverdrup 2010, p. 113.

- ↑ Barthold 1968, pp. 373–380.

- ↑ Golden 2009, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Jackson 2009, p. 31.

- ↑ Sverdrup 2013, p. 37.

- ↑ May 2018, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. V, Ch. 4, "Dynastic and Political History of the Il-Khans" (John Andrew Boyle), p.313 (1968).

- ↑ Stubbs, Kim. "Facing the Wrath of Khan." Military History, May, 2006. p. 30–37.

- ↑ Jaques 2007, p. 778.

- ↑ Sverdrup 2017, pp. 29, 163, 168.

Sources

Medieval

- al-Din, Rashid (1998) [c. 1300]. Jami' al-tawarikh جامع التواريخ [Compendium of Chronicles] (in Arabic and Persian). Vol. 2. Translated by Thackston, W. M. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- al-Hamawi, Yaqut (1955) [c. 1220]. Mu'jam ul-Buldān معجم البلدان [Dictionary of Countries] (in Arabic). Translated by Ibn 'Abdallah ar-Ruml. Beirut.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Chih'ch'ang Li (1888) [c. 1225]. Hsi-yu chi [Travels to the West of Qiu Chang Chun]. Translated by Bretschneider, Emil.

- Juvaini, Ata-Malik (1958) [c. 1260]. Tarikh-i Jahangushay تاریخ جهانگشای [History of the World Conqueror] (in Persian). Vol. 1. Translated by Andrew Boyle, John.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: P-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-33539-6.

- Juzjani, Minhaj-i Siraj (1873) [c. 1260]. Tabaqat-i Nasiri طبقات ناصری (in Persian). Vol. XXIII. Translated by Raverty, H. G.

- al-Nasawi, Shihab al-Din Muhammad (1998) [1241]. Sirah al-Sultan Jalal al-Din Mankubirti [Biography of Sultan Jalal al-Din Mankubirti] (in Russian). Translated by Buniyatov, Z. M.

Modern

- Abazov, Rafis (2008). Palgrave Concise Historical Atlas of Central Asia. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1403975423.

- Ahmad, S. Maqbul (2000). "8: Geodesy, Geology, and Mineralogy; Geography and Cartography". In Bosworth, C.E.; Asimov, M.S. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. IV / #2. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 9231034677.

- Atwood, Christopher P. (2004). Encyclopedia of Mongolia and the Mongol Empire. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-4671-3. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- Barthold, Vasily (1968) [1900]. Turkestan Down to the Mongol Invasion (Second ed.). London: Oxford University Press, Luzac & Co. OCLC 4523164.

- Biran, Michal (2009). "The Mongols in Central Asia from Chinggis Khan's invasion to the rise of Temür". The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age: 46–66. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139056045.006. ISBN 9781139056045.

- Blair, S. (2000). "13: Language Situation and Scripts (Arabic)". In Bosworth, C.E.; Asimov, M.S. (eds.). History of Civilizations of Central Asia. Vol. IV / #2. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. ISBN 9231034677.

- Buell, Paul D. (1979). "Sino-Khitan Administration in Mongol Bukhara". Journal of Asian History (2 ed.). Harrassowitz Verlag. 13 (2): 121–151. JSTOR 41930343.

- Buniyatov, Z. M. (2015) [1986]. A History of the Khorezmian State Under the Anushteginids, 1097-1231 Государство Хорезмшахов-Ануштегинидов: 1097-1231 [A History of the Khorezmian State under the Anushteginids, 1097-1231]. Translated by Mustafayev, Shahin; Welsford, Thomas. Moscow: Nauka. ISBN 978-9943-357-21-1.

- Chalind, Gérard; Mangin-Woods, Michèle; Woods, David (2014). "Chapter 7: The Mongol Empire". A Global History of War: From Assyria to the Twenty-First Century (First ed.). Oakland: University of California Press. JSTOR 10.1525/j.ctt7zw1cg.13.

- Emin, Leon (1989). Muslims in the USSR Мусульмане в СССР [Muslims in the USSR]. Moscow: Novosti Press Agency Publishing House. OCLC 20802477.

- Foltz, Richard (2019). A History of the Tajiks: The Iranians of the East. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1784539559. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Golden, Peter (2009). "Inner Asia c.1200". The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age: 9–25. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139056045.004. ISBN 9781139056045.

- Jackson, Peter (2009). "The Mongol Age in Eastern Inner Asia". The Cambridge History of Inner Asia. The Chinggisid Age: 26–45. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139056045.005. ISBN 9781139056045.

- Man, John (2005). Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 0312314442.

- Martin, H. Desmond (1943). "The Mongol Army". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. Cambridge University Press. 75 (1–2): 46–85. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00098166. S2CID 162432699.

- May, Timothy (2007). The Mongol Art of War : Chinggis Khan and the Mongol Military System. Yardley: Westholme Publishing. ISBN 9781594160462.

- May, Timothy (2018). "The Mongols outside Mongolia". The Mongol Empire. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 44–75. ISBN 9780748642373. JSTOR 10.3366/j.ctv1kz4g68.11.

- May, Timothy (2019). The Mongols. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. ISBN 9781641890953.

- Modelski, George (2007). "Central Asian world cities (XI – XIII century): a discussion paper". Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- Mote, Frederick W. (1999). "The Career of the Great Khan Chinggis". Imperial China 900-1800. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 403–424. doi:10.2307/j.ctv1cbn3m5.21. ISBN 9780674445154. JSTOR j.ctv1cbn3m5.21.

- Nelson Frye, Richard (1997) [1965]. Bukhara: The Medieval Achievement (2nd ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 1568590482.

- Rossabi, Morris (1994). "All the Khan's Horses" (PDF). Natural History. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Smith, John Masson (1975). "Mongol Manpower and Persian Population". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 18 (3): 271–299. doi:10.2307/3632138. JSTOR 3632138.

- Starr, S. Frederick (2013). Lost Enlightenment: Central Asia's Golden Age from the Arab Conquest to Tamerlane. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-15773-3. JSTOR j.ctt3fgz07.

- Sverdrup, Carl (2010). France, John; J. Rogers, Clifford; DeVries, Kelly (eds.). "Numbers in Mongol Warfare". Journal of Medieval Military History. Boydell and Brewer. VIII: 109–117. ISBN 9781843835967. JSTOR 10.7722/j.ctt7zstnd.6.

- Sverdrup, Carl (2013). "Sübe'etei Ba'atur, Anonymous Strategist". Journal of Asian History. Harrassowitz Verlag. 47 (1): 33–49. doi:10.13173/jasiahist.47.1.0033. JSTOR 10.13173/jasiahist.47.1.0033.

- Sverdrup, Carl (2017). The Mongol Conquests: The Military Campaigns of Genghis Khan and Sübe'etei. Warwick: Helion & Company. ISBN 978-1913336059.

- "Historic Centre of Bukhara: UNESCO World Heritage Site". UNESCO: World Heritage Convention. Archived from the original on 4 December 2022. Retrieved 1 March 2023.