| Siege of the fortress at Muluccha | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Jugurthine War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Republic | King Jugurtha of Numidia | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Gaius Marius | Unknown Numidian commander | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 25,000-35,000 | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The siege of the fortress at Muluccha, part of the Jugurthine War, was an investment of a Jugurthine fortress by a Roman army in 106 BC. The Romans were commanded by Gaius Marius, the Numidians by an unknown commander. The Romans main objective was to capture one of king Jugurtha's treasuries which was reported to be inside the fortress. Marius besieged the fortress town and finally took it by trickery.[1]

Background

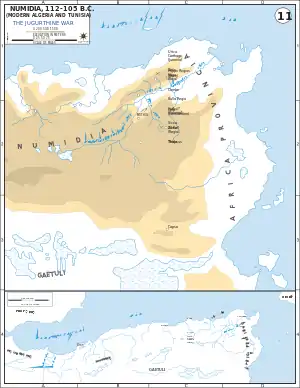

King Masinissa of Numidia, who was a steadfast ally of Rome, died in 149, he was succeeded by his son Micipsa, who ruled from 149 to 118 BC. At the time of his death Micipsa had three potential heirs, his two sons, Adherbal and Hiempsal, and an illegitimate nephew, Jugurtha. Jugurtha had fought under Scipio Aemilianus at the siege of Numantia, where he had formed a friendship with Roman aristocrats and learned about Roman society and military tactics. Micipsa, worried that after his death Jugurtha would usurp the kingdom from his own somewhat less able sons, adopted him, and bequeathed the kingship jointly to his two sons and Jugurtha. After Micipsa's death the three kings fell out, and ultimately agreed between themselves to divide their inheritance into three separate kingdoms. When they were unable to agree on the terms of the division Jugurtha declared open war on his cousins. Hiempsal, the younger and braver of the brothers, was assassinated by Jugurtha's agents. Jugurtha gathered an army and marched against Adherbal, who fled to Rome. There he appealed to the Roman Senate for arbitration.

Although the Senate were securities for Micipsa's will, they now allowed themselves to be bribed by Jugurtha into overlooking his crimes, and organized a commission, led by the ex-Consul Lucius Opimius, to fairly divide Numidia between the remaining contestants in 116 BC. Jugurtha bribed the Roman officials in the commission and was allotted the more fertile and populous western half of Numidia, while Adherbal received the east. Powerless Adherbal accepted and peace was made. Shortly after, in 113 BC, Jugurtha again declared war on his brother, and defeated him, forcing him to retreat into Cirta, Adherbal's capital. Adherbal held out for some months, aided by a large number of Romans and Italians who had settled in Africa for commercial purposes. From inside his siege lines, Adherbal appealed again to Rome, and the Senate dispatched a message to Jugurtha to desist. The latter ignored the demand, and the Senate sent a second commission, this time headed by Marcus Scaurus, a respected member of the aristocracy, to threaten the Numidian king into submission. The king, pretending to be open to discussion, protracted negotiations with Scaurus long enough for Cirta to run out of provisions and hope of relief. When Scaurus left without having forced Jugurtha to a commitment, Adherbal surrendered. Jugurtha promptly had him executed, along with the Romans who had joined in the defence of Cirta. But the deaths of Roman citizens caused an immediate furore among the commoners at home, and the Senate, threatened by the popular tribune Gaius Memmius, finally declared war on Jugurtha in 111 BC.

In 111 BC, the consul Lucius Calpurnius Bestia commanded a Roman army against Jugurtha, but he allowed himself to be bribed. The following year the consul Spurius Postumius Albinus succeeded the command against the Numidian king, but he let himself be bribed too. Spurius's brother, Aulus Postumius Albinus, allowed Jugurtha to lure him into the desolate wilds of the Sahara, where the cunning Numidian king, who had reportedly bribed Roman officers to facilitate his attack, was able to catch the Romans at a disadvantage. Half the Roman army were killed, and the survivors were forced to pass under the yoke in a disgraceful symbolism of surrender. The Roman Senate, however, when it heard of this capitulation, refused to honour the conditions and continued the war.

After Postumius' defeat, the Senate finally shook itself from its lethargy, appointing as commander in Africa the plebeian noble Quintus Caecilius Metellus, who had a reputation for integrity and courage. Metellus proved the soundness of his judgement by selecting as officers for the campaign men of ability rather than of rank, men like Gaius Marius and Publius Rutilius Rufus. Metellus arrived in Africa as consul in 109 BC and dedicated the remainder of the year to a serious disciplinary reform of his demoralised forces. In spring of 108, Metellus led his reorganised army into Numidia; Jugurtha was alarmed and attempted negotiation, but Metellus prevaricated; and, without granting Jugurtha terms, he conspired with Jugurtha's envoys to capture Jugurtha and deliver him to the Romans. The crafty Jugurtha, guessing Metellus' intentions, broke up negotiation and retreated. Metellus followed and crossed the mountains into the desert, advancing to the river Muthul where the Numidians ambushed them. Through the capable leadership of Metellus, Marius and Rutilius Rufus the Romans won an indecisive victory at the Battle of the Muthul. Later that year Metellus surprised Jugurtha by capturing the treasury fortresses at Thala.

The following year (107 BC), one of the new consuls, Gaius Marius, took over command of the war against Jugurtha. Marius marched west plundering the Numidian countryside, seizing minor Numidian towns and fortresses trying to provoke Jugurtha into a set-piece battle, but the Numidian king refused to engage. Marius destroyed the Numidian city of Capsa; after which town after town fell, most without military action. By the beginning of 106 BC, Marius had carved a path of destruction through the Numidian heartland, and subdued most of Jugurtha's kingdom in the process. He now reached one of Jugurtha's primary treasuries, which was kept in a fortress town near the River Muluccha.[2]

The siege

Marius was determined to capture the town and its treasury, but because of the landscape and the location of fortress he was unable to employ the necessary siege engines. Several attempts at storming the fortress ended in failure.[3]

By chance, a Ligurian auxiliary had gone in search of water at the base of the elevated town's rear. Apparently, he was in the mood for snails and went climbing to look for them. As he sought his dinner he found a way onto the plateau and into the town. He returned to the camp and reported what he had discovered. Marius assigned five horn players and four centurions to accompany the Ligurian and infiltrate the town. The Romans created a diversion to draw the defenders attention to the front of the town so the infiltration party could enter via the rear. When the infiltration party was in place Marius ordered a full assault on the town. He sent a testudo towards the gate. While the Numidian were defending against Marius' offensive they suddenly heard horns coming from inside the town. The horns caused confusion and panic,[4] the Romans took advantage of the situation, storming the walls and sacking the settlement.[5]

Aftermath

Jugurtha continued his war against Rome for two more years. Unfortunately for Jugurtha, Marius and his subordinate Sulla were able to convince king Bocchus, Jugurtha's ally and father-in-law, it was in his best interest to abandon his son-in-law. Bocchus conspired with Sulla, who had traveled to Mauretania on a special mission to capture Jugurtha. It was a dangerous operation from the beginning, with King Bocchus weighing up the advantages of handing Jugurtha over to Sulla or Sulla over to Jugurtha. In the end Bocchus decided his future lay with Rome and he helped capture Jugurtha.[6] Although Sulla had engineered the capture of Jugurtha, as Sulla was serving under Marius at the time, Marius took credit for this feat. The publicity attracted by this feat boosted Sulla's political career.

Notes and references

- ↑ Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 82–84.

- ↑ Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 78–82.

- ↑ Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 82–83.

- ↑ the defenders probably assumed the Romans had breached their defences at the rear while they were occupied fighting the frontal assault

- ↑ Marc Hyden, Gaius Marius, pp 83–84.

- ↑ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 3.