Sir Cecil Wray, 13th Baronet (3 September 1734 – 10 January 1805) was an English landowner and politician, and one of the Wray baronets.

Life

Wray was born into an old Lincolnshire family as the eldest and only surviving son of Sir John Wray, 12th Baronet (died 1752), who had married Frances (died 1770), the daughter and sole heiress of Fairfax Norcliffe of Langton, Yorkshire.[1] Cecil was educated at Westminster School (1745) and Trinity College, Cambridge (1749).

On the death of his father in 1752 Cecil succeeded to the baronetcy and to large estates in Lincolnshire, Norfolk, and Yorkshire. He lived in a large house on the north-east side of Eastgate, Lincoln, but, through annoyance from ‘the clanging of anvils in a blacksmith's shop opposite, got disgusted’ with it.[2] He also procured the demolition of the four gatehouses across Eastgate.[3] From 26 December 1755 to 20 December 1757, he was a cornet in the 1st dragoons, and on 17 June 1778 he was appointed captain in the South Lincolnshire militia. He was also captain of a troop of yeomanry.[1]

In 1760, Wray built a ‘Gothic castellated building,’ which he called Summer Castle, after his wife's name, but it has long been known as Fillingham Castle. It stands on a hill about ten miles from Lincoln.

Politics

He contested and won the Parliamentary seat of the borough of East Retford in 1768 as ‘a neighbouring country gentleman and a member of the Bill of Rights Society’ against the interest of the Duke of Newcastle and the corporation, and sat for it in the two parliaments from 1768 to 1780 (Oldfield, Parl. Hist. iv. 340). He acted as chairman of the committee for amending the poor laws, and was one of the strongest opponents of the American war.[1]

On the elevation of Sir George Rodney to the peerage Wray, mainly through the influence of Charles James Fox, was nominated by the whig association to fill the vacancy in the representation of Westminster, and he held the seat from 12 June 1782 to 1784.[1]

Between these dates the Fox–North coalition, between Fox and Lord North had been brought about, and Wray at once denounced the union in the House of Commons. He also opposed with vigour Fox's East India Bill. At the general election in 1784 he stood for Westminster, with the support of the Tories, and in the hope of ousting Fox from the representation. The poll opened on 1 April, and closed on 17 May, when the contest ended, the numbers being Samuel Hood 6,694, Fox 6,233, Wray 5,998. The beaten candidate demanded a scrutiny, which the high bailiff, a tool of the Tories, at once granted, and it was not abandoned until 3 March 1785, when he was ordered by parliament to make his return at once.[1][4]

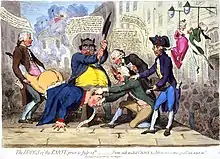

Wray, without possessing ‘superior talents, was independent in mind as well as in fortune’,[5] and had agreeable manners, but he was parsimonious. During the contest of Westminster the wits made themselves merry over his frailties. His ‘small beer’ was ridiculed, the ‘unfinished state of his newly fronted house in Pall Mall’ was sneered at,[6] and he provoked much raillery by his proposals to abolish Chelsea Hospital and to tax maid-servants. Some absurd lines were attributed to him in the ‘Rolliad’,[7] and to him was imputed an irregular ode in the contest for the poet-laureateship.[1][8]

Wray figured in many of Thomas Rowlandson's plates to the ‘History of the Westminster Election, 1784.’ His person reappears as that of a Whig in 1791 in James Gillray's caricatures of "the hopes of the party prior to July 14," and ‘A Birmingham Toast as given on 14 July by the Revolution Society.’ He lived after 1784 in comparative obscurity.[1]

There was published in 1784 ‘A full Account of the Proceedings in Westminster Hall, 14 February 1784, with the Speeches of Sir Cecil Wray and others;’ and Watt mentions under his name the ‘Resolves of the Committee appointed to try the Election for the County of Gloucester in 1777, printed from the Notes of Sir Cecil Wray, the Chairman’.[9]

A full-length portrait by Joshua Reynolds of Sir Cecil Wray is said to be at Sleningford, and there are portraits also at Langton and Fillingham Castle. Miss Dalton of Staindrop possesses a miniature of him, in the uniform of the 1st dragoons, and a full-length portrait by John Opie of him in yeomanry uniform. Lady Wray's portrait was painted in 1767 by Sir Joshua Reynolds. In 1865, it was at Sleningford, near Ripon, the seat of Captain Dalton, and was in fair condition.[1]

Personal

Wray died at Fillingham or Summer Castle, Lincolnshire, on 10 January 1805, and was buried at Fillingham, a tablet being placed in the church to his memory. His wife was Esther Summers, but nothing is known as to her history or the date of their marriage. She died at Summer Castle on 1 February 1825, aged 89, and was buried at Fillingham, where a tablet preserves her memory. They had no issue, and Sir Cecil Wray's estates, which his widow enjoyed for her life, passed to his nephew, Army Officer John Dalton, the son of his sister Isabella.[1]

References

- Attribution

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Courtney, William Prideaux (1900). "Wray, Cecil". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 63. London: Smith, Elder & Co. :

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Courtney, William Prideaux (1900). "Wray, Cecil". In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 63. London: Smith, Elder & Co. :

- Burke's Extinct Baronetcies

- Gent. Mag. 1805 i. 91, ii. 611, 1825 i. 477

- Wraxall's Memoirs (1884 ed.), iii. 18, 80, 284–5, 341–7

- Hist. of Lincolnshire, 1834, p. 39; Monthly Mag. 1805, i. 80–2

- Leslie and Taylor's Sir Joshua Reynolds, i. 282–3

- Charles Dalton's Wrays of Glentworth, ii. 187–214

- Wright and Evans's Gillray Caricatures, pp. 35–36

- Wright's Caricature Hist. of the Georges, pp. 384–98

- Grego's Rowlandson, i. 122–42.

External links

- "Mars and Venus, or Sir Cecil chastised", 1784. by Samuel Collings, at heritage-images.com

- Sir Cecil Wray, Bt, line engraving at the National Portrait Gallery, London