Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Richard Fletcher, 1st Baronet (1768 – 31 August 1813) was an engineer in the British Army known for his work on the Lines of Torres Vedras. He fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and Peninsular Wars, and was mentioned in dispatches a number of times, most notably for his actions at Talavera, Busaco, Badajoz and Vitoria. Fletcher was twice wounded in the line of duty before being killed in action at the Siege of San Sebastian.

Personal life

Little is known of Richard Fletcher's early life, even his exact date of birth is obscure. It is known however that the year was 1768 and his father was a clergyman.[1] On 27 November 1796, at Plymouth, he married Elizabeth Mudge the daughter of a doctor. Fletcher and his wife went on to have five children together; two sons and three daughters.[1] Though Fletcher was buried near to where he was killed at San Sebastián, a monument to his memory, purchased by the Royal Engineers, stands at the western side of the north aisle in Westminster Abbey, London.[2][3]

Early career

Richard Fletcher enrolled as a cadet in the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich on 7 October 1782.[1] He began his career in the Royal Artillery where he became a second-lieutenant on 9 July 1788, before joining the Royal Engineers on 29 June 1790.[1] Fletcher was promoted to lieutenant on 16 January 1793 and when France declared war on Britain, later that year, he was sent to serve in the West Indies.[1]

French Revolutionary Wars

While in the West Indies, Fletcher played an active role in the successful attacks on the French colonies of Martinique, Gaudeloupe and St Lucia, which occurred between February and April 1794. It was during the capture of St Lucia he received a gunshot wound.[1] Fletcher was transferred to the British controlled island of Dominica where he was appointed chief engineer before being sent home at the end of 1796.[1]

While in England, Fletcher served as adjutant to the Royal Military Artificers in Portsmouth until December 1798 when he was sent to Constantinople (now Istanbul) to act as an advisor to the Ottoman Government.[1] Intending to travel through Hanover, Fletcher set sail from England but his ship was wrecked near the mouth of the river Elbe and Fletcher was forced to walk across two miles of ice before reaching land.[1] After three months travelling through Austria and Ottoman territories in the Balkans, Fletcher finally arrived in Constantinople on 29 March 1799.[1] In June 1799, Fletcher, alongside Ottoman troops, advanced into Syria, forcing Napoleon to forgo his siege of Acre and retreat to Egypt.[4]

During 1799, after his return from Syria, Fletcher took part in the preparation of the defences for the Turks in the Dardanelles.[5] After a spell with Ottoman forces in Cyprus, Fletcher returned to Syria in June 1800, to oversee the construction of fortifications at Jaffa and El Arish.[5] Fletcher served under Sir Ralph Abercromby in December 1800 at Marmaris Bay, practising beach assaults for the expected invasion of Egypt the following year.[5] An expedition to reconnoitre the Egyptian port of Alexandria, led to Fletcher's capture when, while returning to his ship after a night reconnaissance mission ashore, Fletcher was intercepted by a French patrol vessel. He was held prisoner in Alexandria until its capture on 2 September 1801.[5]

In October 1801, when the general armistice was signed, Fletcher returned to England, having been promoted to captain while he was imprisoned and later decorated by the Ottoman Empire for his services.[5] The Treaty of Amiens was signed on 25 March 1802 but peace was short-lived and war broke out in May the following year. Fletcher was again sent to Portsmouth where he helped bolster the defences of Gosport.[5] Promoted to major on 2 April 1807, Fletcher took part in the Battle of Copenhagen in August that year.[5]

Peninsular War

Soon after the start of the Peninsular War, Fletcher was sent to Portugal. He was part of the force that occupied Lisbon when the French withdrew following the Convention of Sintra, after which he accompanied Wellington as his chief engineer in the field.[5] Promoted to lieutenant-colonel in the army, 2 March 1809, and then the Royal Engineers, 24 June 1809, he fought at the Battle of Talavera (27-28 July 1809) for which he received a mention in dispatches.[5]

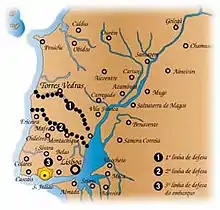

Lines of Torres Vedras

It was while Wellington was making preparations for a retreat to Portugal, that Fletcher became famous for one of the greatest military engineering feats in history. The celebrated Lines of Torres Vedras were constructed on the narrow peninsula between the Atlantic and the Tagus. These three lines of defence; the first 6 miles in front of the principal one and the last 20 miles behind, were intended to protect Lisbon and provide a line of retreat for the British to their ships should it be required.[5] Fletcher began work on these defences on 20 October 1809, using Portuguese soldiers and civilians for the bulk of the labour.[5] Rocky slopes were steepened and reinforced, and defiles were obstructed with forts and earthworks; trees and vegetation were removed to deprive the enemy of cover and sustenance, watercourses were dammed in order to construct impassable lakes or swamps and any buildings were either fortified or destroyed. Fortifications guarded every approach and batteries commanded the highground, while a system of signal stations and roads ensured that troops could be sent quickly to where they were needed the most.[6] And all was conducted with the utmost secrecy so that neither Napoleon nor even the British Government were aware of the lines' existence until Wellington was obliged to retreat behind them later the following year.[3]

In July 1810, shortly before completion of the lines, Fletcher left the fortifications to serve alongside Wellington once more in the field, and was thus at the Battle of Buçaco (27 September 1810) where he again distinguished himself and was mentioned in dispatches.[3] Wellington fell back to the Lines of Torres Vedras in October 1810, pursued by Marshal Masséna, who was shocked to find such extensive defences, having been promised by Portuguese rebels that the road to Lisbon was an easy one. Wellington's superiors were equally surprised to hear about the defences when they later received his report.[3] After an unsuccessful attack on 18 October, Masséna initially retreated to Santarém but when his supplies ran out the following March, he abandoned any thoughts of another attempt and headed north.[3]

Later campaigns

Fletcher, as part of Wellington's forces, chased Masséna to Sabugal where, after some skirmishing, on 2 April, Masséna was finally brought to action at the Battle of Sabugal; the first of a number of engagements as Wellington and Masséna competed for position along the Portuguese and Spanish border.[7] After forcing Masséna to abandon Sabugal, Wellington turned his attention towards Almeida and Ciudad Rodrigo; two fortresses that guarded the northern approach to Portugal. Wellington had planned to capture both while Masséna's army was still in disarray but the loss of Badajoz to Marshall Soult on 11 March, which protected the south, compelled him to divide his force.[8] Wellington sent a quarter of his troops to reinforce General Beresford's, with orders to re-take Badajoz, while his remaining force, which included Fletcher, would lay siege to Almeida. Masséna, now with a superior force, marched to relieve Almeida and Wellington, not wishing to fight under those conditions, withdrew to the town of Fuentes d'Onoro.[9] The town changed hands a number of times during a battle that took place over three days (3–5 May), but ultimately remained under British control.[10] Massénna's troops were neither able to reach the fort nor stay in the open and were thus forced to leave on 8 May.[10] Wellington continued his siege and took possession of Almeida two days later.[3]

Fletcher was again mentioned in dispatches when serving as chief engineer at the second siege of Badajoz (19 May – 10 June 1811).[3] The engineers suffered many casualties in their attempts to dig the thin rocky soils around a fort that had been repaired and reinforced since the last unsuccessful siege. Running short of ammunition and having sustained heavy losses; and with news that French reinforcements were on the way, Wellington withdrew his forces to Elvas on 10 June.[11] Fletcher was also present when Ciudad Rodrigo (7 – 19 January 1812) and, on the third attempt, Badajoz (17 March – 16 April 1812) were captured.[3] In the latter engagement it was Fletcher who identified the weak point in the defences and so ultimately decided where the main attack should be.[12] On 19 March, Fletcher was shot in the groin when a French sortie in the fog reached the trenches where he and his engineers were working. His injury might have been much worse if it had not been for a Spanish Silver Dollar in his pocket which took the main force of the musket ball. Fletcher's injury had him confined to his tent where Wellington, desperately short of good engineers, visited him daily for advice.[12][3] Fletcher returned to England to recover, and was made a baronet on 14 December 1812,[13] and awarded a pension of £1.00 per diem.[3] He received the Portuguese award of the Order of the Tower and Sword;[3] and the Army Gold Cross for Talavera, Bussaco, Ciudad Rodrigo, and Badajoz.[14]

Fletcher returned to the Peninsular in 1813 and received a further mention in dispatches for his role in the Battle of Vitoria on 21 June. Fletcher directed the sieges of Pamplona and San Sebastián. He was killed in action during the final assault on San Sebastián on 31 August 1813.[3]

Memorials

Sir Richard is remembered on a panel commemorating the Peninsular War in Rochester Cathedral.

A memorial in Westminster Abbey was sculpted by Edward Hodges Baily.[15]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Heathcote (p.50)

- ↑ "Famous People - Sir Richard Fletcher". Westminster Abbey History. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster. 2013. Retrieved 29 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Heathcote (p.52)

- ↑ Heathcote (pp.50-51)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Heathcote (p.51)

- ↑ Heathcote (pp.51-52)

- ↑ Heathcote (pp. 52 & 153)

- ↑ Heathcote (p. 153)

- ↑ Heathcote (pp. 153–154)

- 1 2 Heatcote (p. 154)

- ↑ Heathcote (pp. 156–157)

- 1 2 Heathcote (p. 158)

- ↑ "No. 16665". The London Gazette. 10 November 1812. p. 2260.

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography Vol. 19 (p. 326)

- ↑ Dictionary of British Sculptors 1660-1851 by Rupert Gunnis

Bibliography

- Heathcote, T. A. (2010). Wellington's Peninsular War Generals and Their Battles. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84884-061-4.

- Editor: Stephen, Leslie (1889). Dictionary of National Biography, Volume 19. London: Elder Smith & Co.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help)