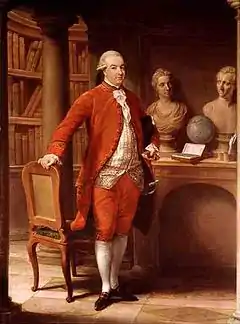

Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 8th Baronet (7 March 1745 – 11 February 1810) was born on 7 March 1745 on the Continent into a devout Catholic gentry family based in Yorkshire. Despite receiving a solid Catholic education at institutions in northern France and Italy, Gascoigne would later renounce his religion to become a Foxite Whig Member of Parliament. Prior to his apostasy, he travelled extensively as a Grand Tourist throughout much of Spain, France and Italy in the company of the noted travel writer Henry Swinburne, who would later record their journeys in two popular travel guides Travels through Spain in the Years 1775 and 1776 (1779) and Travels in the Two Sicilies, 1777–1780 (1783–5). Together they gained close access to the leading courts of Europe, particularly in Spain and Naples. An honorary member of the Board of Agriculture, Gascoigne was an important advocate of agricultural reform as well as a considerable coal owner who helped pioneer technological developments in the extractive industries. He is emblematic of how movements within the Enlightenment were having a major influence on the attitudes, activities and outlook of many leading English Catholic gentry families in the period.[1]

Early life, education and Grand Tour

Sir Thomas Gascoigne was born at the English Benedictine convent at Cambrai, the third son of Sir Edward Gascoigne, 6th Baronet of Parlington Hall, Yorkshire, and his wife, Mary (1711–1764), daughter and heiress of Sir Francis Hungate of Saxton, Yorkshire.[2] The Gascoigne family were a staunch Catholic family and Sir Thomas was raised, and remained, a Catholic until his apostasy for a political preferment and a seat in Parliament in June 1780.[3] He succeeded his elder brother, Sir Edward Gascoigne, 7th Bart., who died of smallpox in Paris in January 1762.[4] He was educated alongside postulants at the English Benedictine school at St Gregory's Priory, Douai, and in 1762, as a result of concerns about his indolence and lack of application, was transferred with a private tutor to study philosophy at the Collège des Quatre-Nations, Paris. Briefly visiting England and his estates for the first time in late 1763, Gascoigne returned to the Continent in January 1764 to attend the academy at Turin, with a new tutor Harry Fermor, which marked in essence the beginning of his first continental Grand Tour - a tour that was designed to introduce him to both elite British and Italian society. At Turin, Gascoigne made the acquaintance of the King of Sardinia Charles Emmanuel III, the British chargé d'affaires Louis Dutens, the distinguished English Catholic natural philosopher John Turberville Needham, and the historian Edward Gibbon; becoming a member of Gibbon's Roman Club upon his return to England later that year.[5] Following his time at the academy, Gascoigne embarked upon a broader tour of Italy in the company of two eccentric friends he had made at Turin, John Damer and his brother George Damer. Sadly, this first tour was to end in tragedy when in March 1765 Gascoigne was implicated, along with George Damer, in the murder of a coachman in Rome. In the aftermath, the Governor of Rome, Cardinal Eneo Silvio Piccolomini, assisted Gascoigne and Damer's escape and even obtained a papal pardon for them from Pope Clement XIII on 6 September 1765.[6]

Following the murder in Rome, Gascoigne was forced to return to England and did not return to the Continent again until 1774. On returning to England, Sir Thomas concentrated on the management of his estates and on county affairs, so far as his religion would allow. In December 1770 he was appointed grand master of the Freemasons of the York Grand Lodge, a position he held until 1772. In 1771 he employed the agriculturalist and gardener John Kennedy, and together the pair experimented with the cultivation of a wide range of plants, though most importantly with the pioneering use of cabbages and carrots as fodder crops for livestock. These experiments would subsequently receive international praise and encouragement most notably from Henry Home, Lord Kames. Gascoigne also spent much of the late 1760s and 1770s extending his estate's mineral assets, which included limestone quarries, coalmines and a small spa at Thorpe Arch, which as a result of Gascoigne's initiatives later became the popular spa resort of Boston Spa.[7] Gascoigne was also committed to horse racing and the breeding of race horses at his stud at Parlington, his horses twice winning the St Leger Stakes in 1778, with Hollandoise, and in 1798 with Symmetry. Some of his racing cups can be seen at Lotherton Hall, near Leeds.[8]

After a hiatus of nine years, Gascoigne returned to the Continent where he was welcomed by court society. Between 1774 and 1779 Gascoigne travelled extensively throughout Europe visiting areas, such as Spain and Italy south of Naples, that received relatively few foreign visitors. Beginning at Spa in the bishopric of Liège where he sought a cure for rheumatism, he was in Bordeaux by April 1775 where he met and befriended the Catholic English travel writer Henry Swinburne who proposed they visit Iberia together. Gascoigne paid the bulk of the costs of the tour to Spain which was planned by Swinburne to form the basis for a published travel guide. The pair arrived in Spain, in October 1775, and toured extensively throughout the country, making long-term friendships with the British ambassador to Spain, Thomas Robinson, 2nd Baron Grantham. The pair were also well received by the Spanish court, gaining the acquaintance of King Charles III who offered them considerable assistance in aiding their tour of the country. Swinburne would later publish a guide based on their tour, Travels through Spain in the Years 1775 and 1776 (1779), which established his reputation as a travel writer.[9] In December 1776 Gascoigne accompanied Swinburne and his family on a visit to southern Italy, based around Naples. Here Gascoigne settled with the Swinburnes and again the pair became intimately connected with the Neapolitan court and British expatriate community. It was thought that their close friendships with King Ferdinand IV and his wife Maria Carolina was strengthened by the fact of their shared Catholicism. Gascoigne accompanied Swinburne on several excursions, which formed the basis for Swinburne's Travels in the Two Sicilies, 1777–1780 (1783–5). In April 1778 Gascoigne travelled with the Swinburne family to Rome where, as well-connected Catholics, they mixed with the city's prominent cultural figures, meeting Pope Pius VI in May 1778, before returning to England in July of the following year.

Politics

Upon returning to England, Gascoigne renounced his Roman Catholic religion in order to circumvent the penal laws and take a seat in Parliament. Alongside his Catholic friend, Charles Howard, Earl of Surrey, Sir Thomas renounced ‘the errors of the Church of Rome before the Archbishop of Canterbury’ on 4 June 1780.[10] Evidence would suggest that his apostasy was motivated solely by his legal need to be an Anglican as a Member of Parliament rather than from any religious conviction. The date he apostatised purposefully coincided with George III's birthday and both Gascoigne and Surrey had earlier been promised parliamentary seats by the Duke of Portland and the Marquess of Rockingham, who had recently bought the seat at Thirsk for which Gascoigne was returned on 12 September 1780. Indeed, privately, Gascoigne seems to have remained Catholic in sympathy throughout his life, continuing to support the Catholic mission in Yorkshire, and only publicly adopted Anglicanism because of the legal need to be an Anglican as an MP.[11]

Gascoigne was a strong supporter of the cause of American Independence and built a commemorative arch to the American victory in the War of Independence, at the entrance to his Parlington Hall estate.[12][13] The main frieze read 'Liberty in N. America Triumphant MDCCLXXXIII' and whilst it categorically supported the American cause, the arch also subtly indicated Gascoigne's approval of Rockingham who had vocally opposed both Lord North, and the war, in Parliament.[14] The Parlington arch still stands and in 1975, on the advice of Nikolaus Pevsner, the British Government made unsuccessful enquiries into the possibility of gifting it to the United States of America to mark the bicentenary of American Independence.[15]

In parliament Gascoigne was a committed Foxite whig and loyal to the Wentworth–Woodhouse connection headed first by Rockingham, and after 1782 by the second Earl Fitzwilliam. At the general election of 1784 Fitzwilliam nominated Gascoigne to be the election manager for the York County election supporting the Foxites Francis Ferrand Foljambe and William Weddell fight against the Pittite candidates William Wilberforce and Henry Duncombe. Despite his best efforts, the county election fell into chaos and Gascoigne's committee declined the poll the night preceding the election.[16] Since December 1782 Gascoigne had been a member of Christopher Wyvill's Yorkshire Association, which agitated for parliamentary reform. Despite eagerly supporting the cause of reform Sir Thomas was forced to resign from the Association during the election when Wyvill came out strongly in support of William Pitt against Fox, nationally, and Fitzwilliam's Wentworth–Woodhouse connection locally in Yorkshire. During the election, Gascoigne was offered the parliamentary seat at Malton, which he held until August 1784.[17]

Between February 1795 and May 1796 Gascoigne was elected MP for Arundel in the gift of his friend Charles Howard, now eleventh Duke of Norfolk (with whom he had earlier apostatised). Despite antagonisms during the Yorkshire election of 1784, Sir Thomas soon renewed his friendship with Christopher Wyvill and together they opposed the Treasonable Practices Act and Seditious Meetings Act (what became popularly known as 'the Two Acts'), with Gascoigne chairing a tumultuous meeting against both bills in York in December 1795. Gascoigne remained committed to Parliamentary reform and in 1797 worked closely with Wyvill in an attempt to revive the reform movement in Yorkshire; the attempt was unsuccessful as by the late 1790s both Wyvill and Gascoigne had lost what little political influence they once had.

In 1788 Sir Thomas became a captain in the 1st West Riding militia, attaining the rank of lieutenant-colonel in 1794, a position from which he resigned in 1798 in support of his patron, the Duke of Norfolk, who had been dismissed from the lord lieutenancy (and de facto command of the militia) for expressing Jacobin sentiments at a political dinner. Three months later Gascoigne took command of a new militia - the Barkston Ash and Skyrack Volunteers.

Later years and personal life

On 4 November 1784, at All Saints' Church, Aston upon Trent, Derbyshire, Gascoigne married Lady Mary Turner, née Shuttleworth (1751–1786), widow of Sir Charles Turner (c.1727–1783). Mary died from complications following childbirth on 1 February 1786, having given birth to a son, Thomas Charles Gascoigne, in the previous month. Gascoigne never remarried and continued to raise his only son and three children from Mary's first marriage on his Parlington estate.[18] His marriage to Mary Turner was Sir Thomas' first and only marriage; the much-repeated claim that he had married a Miss Montgomery in 1772 is incorrect. Although Barbara Montgomery (made famous as one of the graces in Joshua Reynolds's painting Three Ladies Adorning a Term of Hymen (1773)) was certainly romantically attached to Sir Thomas they were never married.[19]

Since inheriting the baronetcy in 1763 Sir Thomas had always taken an active personal interest in the management of the estate and adopted pioneering techniques in both agriculture and the extractive industries, especially in coal mining. His estate comprised property in many of the townships stretching between Tadcaster and Leeds in the West Riding and included not only extensive farmland, but limestone quarries at Huddlestone and coal mines at Parlington, Garforth, Barnbow, Sturton, and Seacroft. Gascoigne was responsive to new developments in the extractive industries and eager to adopt these new techniques to exploit his mineral assets to the full. As a result, he managed to double the vend from his coal mines from some 51,000 tons in 1762 to 115,950 tons in 1810. In late 1790 and again in 1801 Sir Thomas employed the Catholic coal viewer John Curr to advise on his mines. Curr was the colliery steward to Charles Howard, Duke of Norfolk, and was likely to have been recommended to Gascoigne by the Duke.[20] Curr recommended the introduction into the mines of iron tramways underground - some of the earliest introduced in Britain - and the installation of atmospheric steam engines for both draining the pits and winding the coal. The introduction of these measures by Curr, and in particular his iron tramways, significantly extended the working life of each pit and enabled the greater exploitation of coal at the Gascoigne collieries.[21]

Sir Thomas Gascoigne died at Parlington Hall, Parlington, near Aberford, on 11 February 1810 and was buried in the family vault in All Saints' Church, Barwick-in-Elmet. His only son had been killed in a hunting accident four months earlier in October 1809 and it was widely suggested that Sir Thomas's death was hastened by this loss. With no direct descendants the estate passed to Richard Oliver of Castle Oliver in County Limerick — the husband of Mary Turner, Gascoigne's stepdaughter — on condition that he change his name to Oliver Gascoigne.

References

- ↑ Alexander Lock, Catholicism, Identity and Politics in the Age of Enlightenment: The Life and Career of Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 1745-1810 (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2016)

- ↑ Alexander Lock, Catholicism, Identity and Politics in the Age of Enlightenment: The Life and Career of Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 1745-1810 , Studies in Modern British Religious History (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2016).

- ↑ Alexander Lock, ‘Catholicism, Apostasy and Politics in late-Eighteenth-Century England: The Case of Sir Thomas Gascoigne and Charles Howard, Earl of Surrey’, Recusant History, 30 (2010), 275–98

- ↑ Alexander Lock, ‘Gascoigne, Sir Thomas, eighth baronet (1745–1810)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. by David Cannadine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), online edn.

- ↑ Alexander Lock, Catholicism, Identity and Politics in the Age of Enlightenment: The Life and Career of Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 1745-1810 (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2016)

- ↑ West Yorkshire Archive Service, Leeds, WYL115/Box 72 'Pardon Granted by Papal Curia', 6 Sep. 1765.

- ↑ Phyllis Hembry, The English Spa 1560-1815 (London, 1990), pp. 173-4

- ↑ "Carlton Towers, a detailed history". Archived from the original on 24 November 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Kathryn Moore Heleniak, 'An English Gentleman's Encounter with Islamic Architecture: Henry Swinburne's Travels Through Spain (1779)', British Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 28, no. 2 (2005), pp. 181-200

- ↑ London Chronicle, 6 June 1780

- ↑ Alexander Lock, 'Catholicism, Apostasy and Politics in Late Eighteenth-Century England: The Case of Sir Thomas Gascoigne and Charles Howard, Earl of Surrey', Recusant History, vol. 30, no. 2 (2010), pp. 275-298.

- ↑ Article about the Parlington Triumphal Arch.

- ↑ Victoria and Albert Museum website: Search the Collections

- ↑ George Sheeran, 'Patriotic Views: Aristocratic Ideology and the Eighteenth-Century Landscape', Landscapes, vol. 7, no. 2 (2006), pp. 1-23.

- ↑ The National Archives, London, Foreign and Commonwealth Office Records, FCO 13/774, 'Centrepiece for celebrations of bicentenary of USA', 1975.

- ↑ Alexander Lock, 'The Electoral Management of the Yorkshire Election of 1784', Northern History, vol. 47, no. 2 (2010), pp. 271-296.

- ↑ "GASCOIGNE, Sir Thomas, 8th Bt. (1745-1810), of Parlington, Yorks". History of Parliament Online. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ↑ Alexander Lock, ‘Gascoigne, Sir Thomas, eighth baronet (1745–1810)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford: Oxford University Press, May 2013).

- ↑ Alexander Lock, Catholicism, Identity and Politics in the Age of Enlightenment: The Life and Career of Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 1745-1810, Studies in Modern British Religious History (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2016).

- ↑ Alexander Lock, ‘Curr, John (1756–1823)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ed. by David Cannadine (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), online edn.

- ↑ Alexander Lock, Catholicism, Identity and Politics in the Age of Enlightenment: The Life and Career of Sir Thomas Gascoigne, 1745-1810, Studies in Modern British Religious History (Woodbridge: Boydell and Brewer, 2016).