Sir William Wyndham | |

|---|---|

Sir William Wyndham, 1713 portrait by Jonathon Richardson, National Portrait Gallery, London | |

| Chancellor of the Exchequer | |

| In office 1713–1714 | |

| Preceded by | Sir Robert Benson |

| Succeeded by | Sir Richard Onslow |

| Secretary at War | |

| In office 1712–1713 | |

| Preceded by | George Granville |

| Succeeded by | Francis Gwyn |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1688 |

| Died | 17 June 1740 (aged 51–52) |

| Spouse(s) | Lady Catherine Seymour Maria Catherina de Jonge |

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | Sir Edward Wyndham, 2nd Baronet Katherine Leveson-Gower |

| Education | Eton College |

| Alma mater | Christ Church, Oxford |

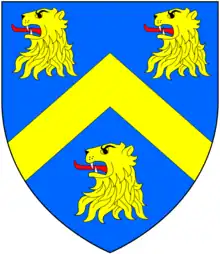

Sir William Wyndham, 3rd Baronet (c. 1688 – 17 June 1740),[1] of Orchard Wyndham in Somerset, was an English Tory politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1710 to 1740. He served as Secretary at War in 1712 and Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1713 during the reign of the last Stuart monarch, Queen Anne (1702–1714). He was a Jacobite leader firmly opposed to the Hanoverian succession and was leader of the Tory opposition in the House of Commons during the reign of King George I (1714–1727) and during the early years of King George II (1727–1760).

His first wife was Lady Catherine Seymour, the younger of the two daughters of Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset (died 1748), and in her children by Wyndham, heiress to half of the vast estates, including Petworth House in Sussex and Egremont Castle in Cumberland, formerly held by the extinct Percy family, Earls of Northumberland. As a result of this complex inheritance his eldest son became the 2nd Earl of Egremont. Both his sons became earls and his daughter Elizabeth Wyndham was both the wife and mother of Prime Ministers, namely George Grenville and William Wyndham Grenville respectively.

He built the pier at Watchet harbour, near Orchard Wyndham.[2]

Origins

He was the son and heir of Sir Edward Wyndham, 2nd Baronet (c. 1667 – 1695) of Orchard Wyndham, three times Member of Parliament for Ilchester, Somerset, by his wife Katherine Leveson-Gower, eldest daughter of Sir William Leveson-Gower, 4th Baronet.

Career

.svg.png.webp)

He was educated at Eton College and Christ Church, Oxford. As a young man while at Rome on his Grand Tour he was approached by a fortune teller who warned him to "beware of a white horse". A similar prophecy was made to him later in England. He later surmised that the white horse in question represented the Saxon Steed in the coat of arms of the Elector of Hanover, the future King George I of Great Britain, his opposition to whom would later cause him much trouble.[2]

He entered parliament as Member of Parliament for Somerset at a by-election on 26 April 1710 and was returned again at the 1710 British general election. He became Secretary at War in the Tory ministry in 1712 and Chancellor of the Exchequer in 1713. He was closely associated with the radical Tory leader Lord Bolingbroke and was privy to the attempts made to bring about a Jacobite restoration on the death of Queen Anne (1702–1714). On the failure of the plot he was dismissed from office,[3] and in 1714 was briefly imprisoned.

Leader of Jacobites

At the start of the reign of the Hanoverian King George I (1714–1727), Bolingbroke fled into exile in France to join the court of the Old Pretender, and Wyndham took his place in England as the leader of the Jacobites. A rebellion to oust King George was planned for the summer of 1715, and Wyndham sent a message to the Pretender in July "not to lose a day in going over".[4] However, the rebellion was discovered and Wyndham's role was laid before the cabinet, attended by both the king and the 6th Duke of Somerset, Wyndham's father-in-law, who although a member of the Whig government and a firm supporter of the Hanoverian Succession, wanted to protect his son-in-law from arrest, and thus volunteered to "be responsible for him". Most ministers were inclined to agree to this for fear of offending a person of such consequence, yet Lord Townshend, Secretary of State for the Northern Department, in the belief that the government needed to show firmness, moved the motion to have him arrested. Ten minutes of silence ensued while the other ministers considered their own responses, and finally two or three others seconded the motion and the arrest was decreed by the king, who on retiring to his closet took Townshend's hand and told him: "you have done me a great service today".[5]

Lord Stanhope brought down to the Commons a message from the King, desiring their consent for apprehending six members of their House on a charge of "being engaged in a design to support the intended invasion of the kingdom",[6] namely[7] Sir William Wyndham, Sir John Pakington, 4th Baronet, Edward Harvey (MP for Clitheroe),[8] Thomas Forster, John Anstis, and Corbet Kynaston. Consent was granted. Harvey and Anstis were in London, and were at once taken. Harvey stabbed himself in the breast in two or three places but his wounds were not mortal. Forster escaped and served as General of the Jacobite army in the 1715 Uprising.

Accordingly, Colonel John Huske of the "foot-guards" (i.e. Coldstream Guards), at about this time an aide-de-camp to William Cadogan, 1st Earl Cadogan, was sent to arrest Wyndham at home at Orchard Wyndham. The story is related in detail by the contemporary commentator Boyer (1716).[9] He was awoken at 5 in the morning and on searching his bedroom the colonel found incriminating papers in his waistcoat pocket, which listed his co-conspirators who planned to invade England and place the Old Pretender on the throne. The colonel had orders to "use him with decorum" and trusted Wyndham when he gave his word that at 7 am, having dressed and said goodbye to his pregnant wife, he would be dressed and ready to depart as the colonel's prisoner, and would even lay on his own coach and six horses for the purpose. Wyndham however escaped by the third unguarded door of his chamber and fled,[9] it is said by having jumped out of a window onto a waiting horse.[2] This caused the king to circulate a hand-bill headed "Proclamation for apprehending Sir William Wyndham, Baronett", dated 23 September 1715, which offered a huge reward of £1,000 for his capture.[lower-alpha 1]

Seeing that his case was hopeless, having for a while disguised himself as a clergyman, he visited his father-in-law the Duke of Somerset at his seat of Syon House, near London. From there he went to London and surrendered himself to the Duke's son and his brother-in-law the Earl of Hertford, a captain in the King's Lifeguards, and was taken into custody[9] in the Tower of London. The 6th Duke of Somerset offered bail to the council for Wyndham's liberty, which was refused. It was soon after having made that offer that the king dismissed him from the high office of Master of the Horse.[5]

Under King George I (1714–1727) and during the early years of King George II (1727–1760) Wyndham was the leader of the Tory opposition in the House of Commons and fought for his High Church and Tory principles against Sir Robert Walpole. He was in constant communication with the exiled Bolingbroke and after 1723 was actively associated with him in abortive plans for the overthrow of Walpole.[3]

"Gumdahm" pseudonym

He appears as "Gumdahm" in the parliamentary reports published from 1738 onwards under the title of the "Debates in the Senate of Magna Lilliputia" in the Gentleman's Magazine, in which to circumvent the prohibition of the publication of parliamentary debates the real names of the various debaters were replaced by pseudonyms and anagrams[lower-alpha 2] and the debates reported were stated to have been "those of that country which Gulliver had so lately rendered illustrious, and which untimely death had prevented that enterprising traveller from publishing himself", that is to say works of fiction in the style of Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels. The published speeches, including some of those of William Pitt, were in fact often literary masterpieces wholly invented by the magazine's contributors, including William Guthrie and Samuel Johnson.[10][lower-alpha 3]

Foundling Hospital

Despite these various enmities, Wyndham was a respected participant in public life in London. He was one of the founding governors of the Foundling Hospital, as recorded in that charity's royal charter of 1739. This was perhaps due to the fact that his father-in-law the 6th Duke of Somerset became a founding governor after his second wife, Charlotte Finch (1711–1773), became the first to sign the petition to King George II of its founder Captain Thomas Coram. This institution, the country's first and only children's home for foundlings, was then London's most fashionable charity and Wyndham served as a governor with such other notables as Thomas Pelham-Holles, 1st Duke of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, James Waldegrave, 1st Earl Waldegrave, Spencer Compton, 1st Earl of Wilmington, Henry Pelham, Arthur Onslow, Horatio Walpole, 1st Baron Walpole of Wolterton and even Sir Robert Walpole himself.[3]

Marriages and children

Wyndham married twice. His first marriage was to Lady Catherine Seymour, the younger of the two daughters of Charles Seymour, 6th Duke of Somerset, KG (1662–1748), and sister of Algernon Seymour, 7th Duke of Somerset (1684–1750). On her brother's death in 1750 she became (with the 7th Duke's only daughter Lady Elizabeth Seymour and her husband Sir Hugh Smithson, 4th Baronet) one of two co-heirs to the vast estates formerly belonging to the ancient Percy family, former Earls of Northumberland, including of Egremont Castle in Cumberland and of the jewel in the crown Petworth House in Sussex, rebuilt in palatial style by her father the 6th Duke, whose first wife had been the great heiress Lady Elizabeth Percy (1667–1722), only daughter and sole heiress of Joceline Percy, 11th Earl of Northumberland (1644–1670) of Petworth House and Alnwick Castle in Northumberland.

By his wife Lady Catherine Seymour he had two sons and three daughters including:

- Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont (1710–1763), of Petworth House, who succeeded as 4th baronet on his father's death in 1740 and in 1750 succeeded as 2nd Earl of Egremont, under a special remainder, on the death of his uncle the 7th Duke of Somerset.[lower-alpha 4]

- Percy Wyndham-O'Brien, 1st Earl of Thomond (c. 1713/23-1774), of Shortgrove, Essex, created in 1756 Earl of Thomond, having adopted the additional surname of O'Brien after having been chosen as heir to his estates by the childless Henry O'Brien, 8th Earl of Thomond (1688–1741), married to his aunt Lady Elizabeth Seymour, the eldest of the two daughters of the 6th Duke of Somerset. He died unmarried and without children when the earldom became extinct.

- Elizabeth Wyndham, wife of George Grenville, Prime Minister and mother of William Wyndham Grenville, Prime Minister.

Sir William's second wife was Maria Catherina de Jonge, the widow of William Godolphin, Marquess of Blandford.[3]

Death and burial

He died at Wells, Somerset, on 17 June 1740, after having fallen from his horse ("white of course"[2]), whilst out hunting.[lower-alpha 5]

Portraits

Portraits of Sir William Wyndham survive at Orchard Wyndham, Petworth House and other Wyndham family properties[14]

Notes

- ↑ See image aside. A transcription is on the image page.

- ↑ For example Sholmlng for Cholmondeley and Ptit for Pitt

- ↑ Emeny, p.3, appears to have understood erroneously that "Gumdahm" was a character in Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels

- ↑ Shortly before his death in 1748 the 6th Duke of Somerset foresaw that his own line of the Seymour family was about to die out in the male line and that as was said of the 9th Duke of Norfolk (died 1777) "the honours of his family were about to pass away from his own line to settle on that of a distant relative".[11] His son and heir apparent Algernon Seymour, Earl of Hertford (1684–1749) had produced a son of his own, Lord Beauchamp (died 1744), who had predeceased him without children, and thus he had only a daughter and sole heiress Lady Elizabeth Seymour, who in 1740 had married Sir Hugh Smithson, 4th Baronet. Before the death of the 6th duke in 1748, it had thus become apparent that the dukedom of Somerset would devolve by law onto an extremely distant cousin and heir male, the 6th duke's 6th cousin Sir Edward Seymour, 6th Baronet (1695–1757) of Berry Pomeroy in Devon and of Maiden Bradley in Wiltshire, who in fact represented the senior line of the Seymour family, descended from the first marriage of the 1st Duke, but who had been excluded from the direct succession to the dukedom and placed in remainder only, due to the suspected adultery of the 1st duke's first wife. Moreover, it was apparent that all the combined estates of the Seymours of Trowbridge and the incomparably greater inherited Percy estates were unentailed and would not devolve the same way, but could be bequeathed as the 6th duke pleased. He "conceived a violent dislike for Smithson",[12] whom he considered insufficiently aristocratic to inherit the ancient estates of the Percy family; his son disagreed, and wanted to include his son-in-law Smithson in the inheritance. The 6th Duke had included King George II in his plan to exclude Smithson from the inheritance, yet the King had received proposals in opposition from his son and Smithson himself. The 6th Duke died before his plan was put into effect, yet nevertheless the 7th Duke and King George II created an arrangement which did not entirely dismiss his wishes: the Percy estates would be split between Smithson and the 6th duke's favoured eldest grandson, Sir Charles Wyndham, 4th Baronet (1710–1763). Smithson would receive Alnwick Castle and Syon House, while Wyndham would receive Egremont Castle and the 6th Duke's beloved Petworth. It was deemed appropriate and necessary by all parties concerned, including the King, that heirs to such families and estates as the Percys and Seymours should be elevated to the peerage. This was done in the following manner: Following the 6th duke's death in 1748, in 1749 King George II created four new titles for the 7th duke, each with special remainders in anticipation that he would die without having produced a male heir, which death in fact occurred the next year in 1750. He was created Baron Warkworth of Warkworth Castle and Earl of Northumberland, both with special remainder to Smithson; and was created at the same time Baron Cockermouth and Earl of Egremont, with special remainder to Wyndham.[13] (It has always been customary on the creation of a greater peerage title to create at the same time a barony, to be used as a courtesy title for the eldest son).

- ↑ Emeny, p.3, referring to the warning he had received as a young man in Rome "Beware of a white horse"

References

- ↑ Stephen W. Baskerville, "Wyndham, Sir William, third baronet (c. 1688 – 1740)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 Emeny, Richard, A Description of Orchard Wyndham, 2000, p.3 (guide-booklet available at Orchard Wyndham)

- 1 2 3 4 Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Wyndham, Sir William". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 872–873.

- ↑ Cruickshanks, Eveline, Wyndham, Sir William, 3rd Bt. (?1688-1740), of Orchard Wyndham, Somerset, published in History of Parliament: House of Commons 1715-1754, ed. R. Sedgwick, 1970

- 1 2 Cobbet, William, Cobbett's Parliamentary History of England, Volume 7, London, 1811, pp. 218–9.

- ↑ Cruickshanks, Eveline, Forster, Thomas (1683-1738), of Adderstone, Northumb., published in History of Parliament: House of Commons 1715-1754, ed. R. Sedgwick, 1970

- ↑ Arnold, Frederick H. (1879). "Notes and Queries. Proclamation against Sir W. Wyndham" (PDF). Sussex Archaeological Collections. 29: 235–236.

- ↑ Watson, Paula; Harrison Richard, Harvey, Edward (1658-1736), of Coombe, Surr., published in History of Parliament: House of Commons 1690-1715, ed. D. Hayton, E. Cruickshanks, S. Handley, 2002

- 1 2 3 Boyer, Abel, Political State of Great Britain, Volume X, London, 1716, pp. 330–6

- ↑ Graham, Harry, The Mother of Parliaments, Boston USA, 1911, pp. 279–80.

- ↑ Tierney, M.A., History and Antiquities of Arundel, 1833, Chapter 6, p.565, note 4,

- ↑ Cruickshanks, Eveline, Smithson, Sir Hugh, 4th Bt. (1715-86), of Stanwick, Yorks. and Tottenham, Mdx., published in The History of Parliament: the House of Commons 1715-1754, ed. R. Sedgwick, 1970

- ↑ Debretts peerage, 1968, p.411, Baron Leconfield and Egremont

- ↑ Art UK. "Sir William Wyndham (1687–1740), 3rd Bt, MP, on Horseback John Wootton (c.1682–1764) and Michael Dahl I (1656/1659–1743), National Trust, Petworth House" (image of portrait not currently available). Retrieved 4 December 2016.

_(2022).svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)