Skat scoring (German: Skatabrechnung) refers to the method of recording of game points in the card game of Skat. Since it is normal for a number of rounds to be played, not just a single game, there is a need to record and account for the game points won by each individual in order to determine the overall result. A proper scoring system is especially important for the Tournament Skat and Skat played for small stakes.

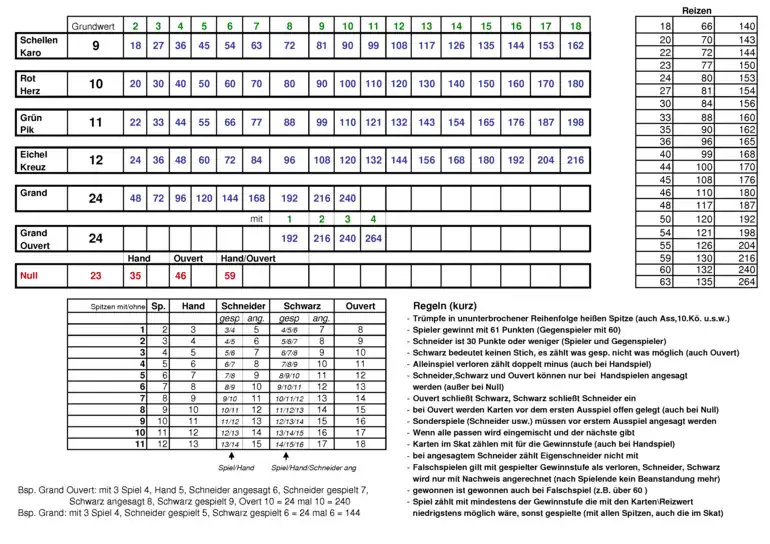

Game value

The game value is determined according to the rules described under "Bidding" at the Skat article. Outside of official tournaments, other rules may be agreed privately at the table that affect the game value enormously. Such variants can be found under "Alternative game values" at that article.

Example

A three-player round is played. The following example is used as a template.

- Anton wins a Grand with four Jacks and Schneider. He receives 144 points. ("With 4, game 5, Schneider 6, x 24)

- Anton only has the ♥J and loses a Diamond game. He loses 54 points. ("Without 2, game 3, lost 6, x 9)

- Carla wins a Null Ouverte. She gets 46 points. (fixed game value of 46)

Calculation of game points

Since there can be different game objectives, different methods of writing down the score have developed. In addition, the 14th and 18th Skat congresses tried to control game behaviour with the changes in scoring scheme.

Classic variant

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| +144 | 0 | 0 |

| +90 | 0 | 0 |

| +90 | 0 | +46 |

In the most common method, the game points scored are always assigned to the soloist. If the game has been won, the game value is added to the soloist's score. If the game was lost, double the game value is deducted from the soloist. The table shows the cumulative scoring in each case (e.g. when Anton loses the second game, 108 is deducted from his total, leaving him with 36).

This form of scoring goes back to the point bidding system developed in the second half of the 19th century, which only became officially established in 1923 with the Skat Regulations for Leipzig Skat (Skatordnung für den Leipziger Skat') by Artur Schubert and which finally prevailed in 1927. Because this form of the game, the scoring and bidding spread among German soldiers during the First World War, it was also called Trench Skat (Schützengrabenskat or Grabenskat). Modern Skat is based on this variant, which was historically also referred to as Leipzig Skat.[1]

Extended Seeger and Fabian system

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| +194 | 0 | 0 |

| +90 | +40 | +40 |

| +90 | +40 | +136 |

In the Extended Seeger System, the soloist receives a bonus of 50 points for each game won in addition to its game value. For every lost game, 50 points and double the game value is deducted. At a three-player table, the opponents receive 40 points each if the soloist loses. At a four-player table, the opponents and the non-active player/dealer get 30 points each for every lost game. The Extended Seeger System does not work well on tables with more than four players (however on the German Skat Association's competition list, 24 points are envisaged for five-player tables). The Seeger/Fabian points are not taken into account in the Skat played for small stakes.

In order to give even low value suit games a higher value, a system proposed by Otto Seeger was introduced in 1936. In addition to the game value, the soloist received 50 points for each game won. This regulation meant that lost games could be compensated for more quickly, which increased players' willingness to take risks when bidding. AT the 18th Skat congress in 1962, the scoring system was supplemented by a proposal by Johannes Fabian. The new scheme, known as the Extended Seeger and Fabian system (Erweitertes System nach Seeger und Fabian) or Extended Seeger System (Erweitertes Seeger-System) is still the basis for the official tournament Skat. While the old Seeger system only awarded bonus points for games won, a bonus for the opponents and dealer in lost games are now also calculated. The relationship between the effect of a lost and a game won was more balanced again. [2]

Bierlachs

| A | B | C |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | −144 | −144 |

| −54 | -144 | -144 |

| −100 | −190 | -144 |

In Bierlachs there is a widespread unofficial variant of the scoring system, in which the value of a game won is scored as a negative amount by the losing (active) players. In a four-player game the dealer 'sits out'; nevertheless, in a game won by the soloist, all three losing players get the corresponding minus points. A lost game is entered in the classic way with a double minus value for the solo player.

Bierlachs is not just an alternative scoring scheme, but a fundamentally different game. The aim of the game is not to exceed a previously agreed target value. While the goal in classic Skat is to win. In Bierlachs it is about not losing, which is why the play tactics differ. In general, the limit at a three-player table is 301 and at a four-player table 401. If a player exceeds the target i.e. accumulates more minus points than the limit set, that player loses the round. The game is usually played for drink, hence the name.

Tournament Skat

In Tournament Skat all the participants pay an entry fee. The overall winner is the one who has scored the most points after a certain number of games. The winners may receive prizes paid for from the entry fees or even a sum of money. For scoring purposes the Extended Seeger and Fabian System is usually used. In addition to the official scoring, there is often a special monetary settlement at individual tables that is agreed privately.

Skat played for small stakes

Each game was originally paid immediately, i.e. the game value was multiplied by the agreed rate in relation to the currency being used and was immediately paid out to the winner. For this purpose, there were special gaming tables with coin compartments at every place.

Nowadays it is common, as described above to record the game points and carry out a final settlement after the end of the game. Points from the Extended Seeger and Fabian System are excluded. This additional calculation is necessary because the scoresheet gives the ranking of the players, but not who should pay whom. After the calculations, the values are multiplied by an agreed tariff in order to convert points into hard cash. In practice, stakes of 1 cent or a fraction of a cent as 1/2, 1/4 or 1/10 are common.

Multiplier methods

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| +90 | 0 | +46 | Individual totals |

| +270 | 0 | +138 | Totals x number of players (three-player table) |

| +136 | +136 | +136 | Sum of individual totals |

| +134 | -136 | +2 | Difference between the two values |

The multiplier methods are referred to as Variant 1 and Variant 2 in the International Skat Regulations of 22 November 1998.[3] The differences between the two variants lies in the choice of sign. The calculation shown in the example table corresponds to the Variant 1.

Variant 1

If the individual scores are predominately plus points, they are first multiplied by the number of players, noting the sign, and then the sum of the individual scores is deducted from each player's total.[3]

Variant 2

If the individual totals are predominantly negative, they are first multiplied by the number of players and then the sum of the individual scores is added to each player's total.[3]

Difference scoring

| A | B | C | |

|---|---|---|---|

| +90 | 0 | +46 | Individual totals |

| +90 | −90 | Difference between A and B | |

| +44 | −44 | Difference between A and C | |

| −46 | +46 | Difference between B and C | |

| +134 | -136 | +2 | Sum of the differences |

The difference method is referred to as Variant 3 in the International Skat Regulations.[3]

Each individual total is compared with the other 2 or 3 totals, i.e. the individual totals of the other players, taking account the signs. In the end, the comparison values of the individual players are added up.

As with the multiplication method, the result must then be multiplied by tariff to determine values in real currency.

For all the variants described, this means in relation to the selected example: Anton gets 134 times the tariff. Bert must pay 136 times the tariff and Carla wins the twice the tariff.

References

- ↑ Geschichte des Skat at the Wayback Machine (archived 3 July 2012)

- ↑ Schettler & Kirschbach (1989), p. 171.

- 1 2 3 4 Extract from the International Skat Regulations

Literature

- Bernhard Kopp: Gewinnen beim Skat, Books on Demand GmbH, Norderstedt, 2nd edn. 2004, ISBN 3-8334-1267-4

- Frank Schettler and Günter Kirschbach: Das große Skatvergnügen: die hohe Schule des Skatspiels. Rosenheimer. ISBN 3-475-52593-3. 239 pp.