| Part of a series on |

| Slavic Native Faith |

|---|

|

In the Russian intellectual milieu, Slavic Native Faith (Rodnovery) presents itself as a carrier of the political philosophy of nativism/nationalism/populism (narodnichestvo),[1] intrinsically related to the identity of the Slavs and the broader group of populations with Indo-European speaking origins,[2] and intertwined with historiosophical ideas about the past and the future of these populations and their role in eschatology.[3]

The scholar Robert A. Saunders found that Rodnover ideas are very close to those of Eurasianism, the current leading ideology of the Russian state.[4] Others found similarities of Rodnover ideas with those of the Nouvelle Droite (European New Right).[5] Rodnovery typically gives preeminence to the rights of the collectivity over the rights of the individual,[6] and Rodnover social values are conservative.[7] Common themes are the opposition to cosmopolitanism, liberalism, and globalisation,[8] as well as Americanisation and consumerism.[9]

The scholar Kaarina Aitamurto defined Rodnovers' applied political systems as forms of grassroots democracy, or as a samoderzhavie ("self-rule") system, based on the ancient Slavic model of the veche (assembly) of the elders, similar to ancient Greek democracy. They generally propose a political system in which power is entrusted to assemblies of consensually acknowledged wise men, or to a single wise individual.[10] On the level of geopolitics, Rodnovers have proposed the idea of "multipolarity" to oppose the "unipolarity" of the mono-ideologies, that is to say the Abrahamic religions and their ideological products of the Western civilisation.[11]

The historian Marlène Laruelle observed that Rodnovery is in principle a decentralised movement, with hundreds of groups coexisting without submission to a central authority. Therefore, socio-political views can vary greatly from one group to another, from one adherent to another, ranging from apoliticism, to left-wing, to right-wing positions. Nevertheless, Laruelle said that the most politicised right-wing groups are the most popularly known, since they are more vocal in spreading their ideas through the media, organise anti-Christian campaigns, and even engage in violent actions.[12] Aitamurto observed that the different wings of the Rodnover movement "attract different kinds of people approaching the religion from quite diverging points of departure".[13] Aitamurto and Victor Shnirelman also found that the lines between right-wing, left-wing and apolitical Rodnovers is blurry.[14]

In 1997 some Russian Rodnovers published a political declaration, the Russian Pagan Manifesto, which mentions, as sources of inspiration, three figures famous for their strong nationalism and conservatism: Lev Gumilyov, Igor Shafarevich, and the Iranian Ruhollah Khomeini. In 2002, the Bittsa Appeal was promulgated by Rodnovers less political in their orientation, and among other things it explicitly condemned extreme nationalism within Rodnovery. A further Rodnover political declaration, not critical towards nationalism, was the Heathen Tradition Manifest published in 2007.[15]

Origins of the Slavs

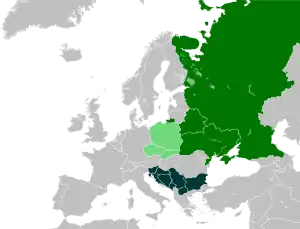

The notion that modern Rodnovery is closely tied to the historical religion of the Slavs is a very strong one among practitioners.[16] Although there is no surviving evidence that the early Slavs, a branch of the Indo-Europeans, conceived of themselves as a unified ethno-cultural group,[17] the reconstruction of the Proto-Slavic language and the principles of historical linguistics indicates that there must have been a Proto-Slavic people tight-knit enough to have spoken a single language or at least closely related groups of dialects that differentiated them greatly from surrounding populations. There is an academic consensus that the Proto-Slavic language developed from about the second half of the first millennium BCE in an area of Central and Eastern Europe bordered by the Dnieper basin to the east, the Vistula basin to the west, the Carpathian Mountains to the south, and the forests beyond the Pripet basin to the north.[18]

Over the course of several centuries, Slavic populations migrated in northern, eastern, and south-western directions.[18] In doing so, they branched out into three sub-linguistic families: the East Slavs (Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians), the West Slavs (Poles, Czechs, Slovaks), and the South Slavs (Slovenes, Serbs, Croats, Macedonians, and Bulgarians).[18] The belief systems of these Slavic communities had many affinities with those of neighbouring linguistic populations, such as the Balts, Thracians, and Indo-Iranians.[18]

Vyacheslav Ivanov and Vladimir Toporov studied the origin of ancient Slavic themes in the common substratum represented by the reconstructed purported Proto-Indo-European religion and what Georges Dumézil defined as the "trifunctional hypothesis". Marija Gimbutas, instead, found Slavic religion to be a clear result of the overlap of supposed Indo-European patriarchism and pre-Indo-European matrifocal beliefs, such proposed duality being a common theme in her studies about so-called "Old Europe" and the Kurgan hypothesis. Boris Rybakov emphasised the continuity and complexification of Slavic religion through the centuries.[18] According to the scholar of religion Mircea Eliade, the original Proto-Indo-European religious traditions were closer to Siberian shamanism than to the later Near Eastern and Mediterranean religions, as proven by their shared crucial concepts: the supreme God of Heaven (cf. Indo-European Dyeus, Siberian Tengri, and Mesopotamian Dingir) and the three-layered structure of cosmology (cf. Sanskrit Trailokya).[19]

Rodnover political ideologies

Veche democracy

.jpg.webp)

Many Russian Rodnover groups are strongly critical of democracy, modern liberal democracy, which they see as a degenerate form of government that leads to "cosmopolitan chaos". According to Shnirelman they favour instead political models of a centralised state led by a strong leader.[20] Aitamurto, otherwise, characterises the political models proposed by Rodnovers as based on their interpretation of the ancient Slavic community model of the veche (assembly), similar to the ancient Germanic "thing".[21] Nineteenth- and twentieth-century intellectuals often interpreted the veche as an anti-hierarchic and democratic model, while later Soviet Marxist tended to identify it as "pre-capitalist democracy". The term already had ethnic and national connotations, which were underlined by nineteenth-century Slavophiles, and nationalist circles in the last decades of the Soviet Union and from the 1990s onwards.[22]

Many Rodnover groups call their organisational structure veche. Aitamurto found that it proves to be useful in what she terms as Rodnovery's "democratic criticism of democracy" (of liberal democracy). According to her, the veche as interpreted by Rodnovers represents a vernacular form of governance similar to ancient Greek democracy. According to the view shared by many Rodnovers, while liberal democracy ends up in chaos because it is driven by the decisions of the masses, who are not wise; the veche represents a form of "consensual decision-making" of assemblies of wise elders, and power is exercised by wise rulers. Ynglists call this model samoderzhavie, "people ruling themselves".[23] Anastasians give to "self-government" and consensual decision-making a theological interpretation, viewing it as realising the "thought of God" through people.[24] However, Aitamurto also described many Rodnovers' political philosophy as elitism, in which not everyone is reputed as having the same decision ability; the most conservative Rodnovers espouse the ideal that "the opinion of a prostitute cannot have the same weight as the opinion of a professor".[25]

Western liberal ideas of freedom and democracy are traditionally perceived by Russian eyes as "outer" freedom, contrasting with Slavic "inner" freedom of the mind; in Rodnovers' view, Western liberal democracy is "destined to execute the primitive desires of the masses or to work as a tool in the hands of a ruthless elite", being therefore a mean-spirited "rule of demons".[26] The Anastasians describe modern Western democracy as a system of control through conflict, which always inevitably produces disaffected sections in the population, and through money; in their books, The Ringing Cedars, democracy is criticised as "demonocracy" through a myth in which it is personified as "Demon Cratiy" (Демон Кратий), a demon who invented such system as a way to subordinate all people to the monetary system through the illusion of freedom.[27]

In these ideas of grassroots democracy which comes to fruition in a wise governance, Aitamurto saw an incarnation of the traditional Russian challenge of religious structures and alienated governance—such as autocratic monarchy and totalitarian communism—for achieving a personal relationship with the sacred, which is at the same time a demand of social solidarity and responsibility. She presents the interpretation of the myth of Perun who slashes the snake guilty of theft, provided by the Russian volkhv Velimir (Nikolay Speransky), as symbolising the ideal relationship and collaboration between the ruler and the people, with the ruler serving the people who have chosen him by acting as an authority who provides them with order, and in turn is respected by the people with loyalty for his service.[28] Some Rodnovers interpret the veche in ethnic terms, thus as a form of "ethnic democracy", in the wake of similar concepts found in the Nouvelle Droite.[5]

Nationalism

The scholar Scott Simpson stated that Slavic Native Faith is fundamentally concerned with ethnic identity.[29] This easily develops into forms of nationalism,[30] and has often been characterised as ethnic nationalism.[31] Aitamurto suggested that Russian Rodnovers' conceptions of nationalism encompass three main themes: that "the Russian or Slavic people are a distinct group", that they "have—or their heritage has—some superior qualities", and that "this unique heritage or the existence of this ethnic group is now threatened, and, therefore, it is of vital importance to fight for it".[32] According to Shnirelman, ethnic nationalist and racist views are present even in those Rodnovers who do not identify as politically engaged.[33] He also noted that the movement is "obsessed with the idea of origin",[33] and most Rodnover groups will permit only Slavs as members, although there are a few exceptions.[34] There are Rodnover groups that espouse less radical positions of nationalism, such as cultural nationalism or patriotism.[35]

Conservatism, anti-miscegenation and eugenics

The ethics of the Rodnovers in general emphasise the conservative values typical of the political right-wing: patriarchy, heterosexuality, traditional family, fidelity and procreation.[7] Many Rodnovers believe in casteism, the idea that people are born to fulfill a precise role and business in society; the Hindu varna system with its three castes — priests, warriors and peasants-merchants — is taken as a model, although in Rodnovery it is conceived as an open system rather than a hereditary one.[36]

Along with these values, some Rodnover groups are against miscegenation, the mixing of different races carriers of different cultures. In its founding statement from 1998, the Federation of Ukrainian Rodnovers led by the Ukrainian Rodnover leader Halyna Lozko declared that many of the world's problems stem from the "mixing of ethnic cultures", something which they claim has resulted in the "ruination of the ethnosphere", which they regard as an integral part of the Earth's biosphere.[37] Rodnovers generally conceive ethnicity and culture as territorial, moulded by the surrounding natural environment (ecology).[38] Similarly, Lev Sylenko, founder of the Ukrainian branch of Rodnovery known as the Native Ukrainian National Faith, taught that humanity was naturally divided up into distinct ethno-cultural groups, each with their own life cycle, religiosity, language, and customs, all of which had to spiritually progress in their own way.[39] Therefore, many Rodnovers emphasise a need for ethnic purity and oppose what they regard as the "culturally destructive" phenomena brought about by liberal globalisation.[8]

Racial purity is biological terms is particularly important for the denomination of the Ynglists,[40] who abhor miscegenation as unhealthy, and abhor as well what are perceived as perverted sexual behaviours and the consumption of alcohol and drugs which ruin the genetic health of a people.[41] According to the Ynglists, miscegenation and perverted behaviours are evil influences which come from the degenerating West and threaten the health of Russia; in order to counterweigh them, the Ynglists promote policies such as the eugenic idea of "creation of beneficial descendants" (sozidanie blagodetel'nogo potomstva).[41] Some Rodnovers have demanded to make mixed-race marriages illegal in their countries.[34]

Ethno-states

There are Russian Rodnovers who promote the common views of Russian nationalism: some seek an imperialist policy that would expand Russia's territory across Europe and Asia, while others seek to reduce the area controlled by the Russian Federation to only those areas with an ethnic Russian majority.[42] The place of nationalism, and of ethnic Russians' relationship to other ethnic groups inhabiting the Russian Federation, has been a key issue of discussion among Russian Rodnovers.[43] Some express xenophobic views and encourage the removal of those regarded as "aliens" from Russia, namely those who are Jews, Caucasian Muslims, and more broadly Asians.[44]

For these Rodnovers, ethnic minorities are viewed as the cause of social injustice in Russia.[34] According to Shnirelman, given that around 20% of the Russian Federation is not ethnically Russian, the ideas of ethnic homogeneity embraced by many Russian Rodnovers could only be achieved through ethnic cleansing.[34] Aitamurto noted that the territorial release of several of the majority non-Russian republics of Russia and autonomous okrugs of Russia would result in the same reduction of ethnic minorities in Russia without any need for violence whatsoever, which is the approach called for by peaceful Russian Rodnovers.[42]

Nazism and communism

Shnirelman observed that many Russian Rodnovers deny or downplay the racist and National Socialist elements within their community,[45] while there are various Rodnover groups in Russia which are openly inspired by Nazi Germany.[46] Among those groups that are ideologically akin to Neo-Nazism, the term "Nazi" is rarely embraced, in part due to the prominent role that the Soviet Union played in the defeat of Nazi Germany.[47] The scholar Dmitry V. Shlyapentokh observed that Neo-Nazism in Russia is not a direct imitation of the German type, but developed as a response to the peculiar political climate of contemporary Russia.[48] The volkhv Dobroslav (Aleksey Dobrovolsky)—who held a position of high respect within Russia's Rodnover community—called his political idea a new "Russian national socialism" or "Pagan socialism", entailing "harmony with nature, a national sovereignty and a just social order".[49]

Another school of thought, leaning towards communism, is that of volkhv Vseslav Svyatozar (Grigory Yakutovsky), who formulated instead an idea of "social communism".[50] Some Rodnovers claim that those who adopt extreme political views are not true Rodnovers because their interests in the movement are primarily political rather than religious.[45] According to the scholars Hilary Pilkington and Anton Popov, Cossack Rodnovers generally eschew National Socialism and racial interpretations of Aryanism.[51]

Multipolarity versus unipolarity in geopolitics

On the geopolitical stage, the Rodnover movement has proposed the concept of "multipolarity", that is to say of a world of many power centres, well represented by the "Russian Way", to contrast the "unipolarity", the "unipolar" world, created by the mono-ideologies—the Abrahamic religions and their other ideological products—and led by the United States of America-dominated West. In their view, while the unipolar world is characterised by the materialism and selfish utilitarianism of the West, the multipolar world represented by Russia is characterised by spirituality, ecology, humanism and true equality. The idea of Russian multipolarity against Westernising unipolarity is popular among Russian intellectuals, and among Rodnovers it was first formally enunciated in the Russian Pagan Manifesto of 1997.[11]

Antisemitism and philosemitism

Many Russian practitioners are openly antisemite,[52] a category which for them means not only anti-Jewish sentiments, but more broadly anti-Asian, anti-Christian and anti-Islamic, and anti-Byzantinist sentiments,[53] and espouse conspiracy theories claiming that Jews and Asians control the economic and political elite and aim at the destruction of the Russians,[44] after having subjugated the Aryan Europeans, including Russians, through Christianity, "which in itself is evil for all mankind", and through the "repressive machinery" of the Byzantinist model of state.[54] Shlyapentokh noted that the unique philosemitism of contemporary Russian politics, which for the first time in history benevolently supports Jews and Muslims alongside Orthodox Christians in the fabric of Russian society, led to the identification of much of the right-wing with Paganism, and to the rise of the characteristic theories of contemporary Russian antisemitism.[48] In Ukraine too, the Rodnover leader Halyna Lozko produced a prayer manual titled Pravoslav in which "Don't get involved with Jews!" was listed as the last of ten "Pagan commandments".[55] Similar views are also present within the Polish Rodnover community.[56]

Yet other Rodnovers have admiration for the Jews, and for powerful Russian Jews such as Roman Abramovich, considering them as a smart race on par with the Aryans; some writings such as The Mysterious Russian Soul Against the Background of World Jewish History claim that Russians should not view Jews as a completely alien race, since the Jews contributed to Russian history and the Russians themselves have a lot of Jewish blood.[57] Some Rodnovers, such as the Kandybaites, consider the Asians, together with the Russians, as part of the East dominated by the bright spiritual component of humanity, opposed to the West dominated by the dark beastly component, and consider the Jews to be a branch of the "southern Russians", the Khazars.[58]

Apoliticism

Trends of de-politicisation of the Russian Rodnover community have been influenced by the introduction of anti-extremist legislation,[59] and the lack of any significant political opposition to the United Russia government of Vladimir Putin.[6] Simpson noted that in Poland, there has been an increasing trend to separate the religion from explicitly political activities and ideas during the 2010s.[60] The Russian Circle of Pagan Tradition recognises Russia as a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural state, and has developed links with other religious communities in the country, such as practitioners of Mari Native Faith.[61] Members of the Circle of Pagan Tradition prefer to characterise themselves as "patriots" rather than "nationalists" and seek to avoid any association with the idea of a "Russia for the Russians".[62] The scholars Kaarina Atamurto and Roman Shizhenskii found that expressions of ultra-nationalism were considered socially unacceptable at one of the largest Rodnover events in Russia, the Kupala festival outside Maloyaroslavets.[63] Rodnovers of the settlement of Pravovedi located in Kolomna, Moscow Oblast, reject the very idea of "nation" and conceive peoples as "spirits" manifesting themselves according to the law of genealogy, the law of the kin.[64]

Rodnover historiosophy

Historiosophical narratives and interpretations vary between different currents of Rodnovery,[65] and accounts of the historical past are often intertwined with eschatological views about the future.[66] Many Rodnovers magnify the ancient Slavs by according to them great cultural achievements.[67] Aitamurto observed that early Russian Rodnovery was characterised by "extremely imaginative and exaggerated" narratives about history.[68] Similarly, the scholar Vladimir Dulov noted that Bulgarian Rodnovers tended to have "fantastic" views of history.[69] However, Aitamurto and Alexey Gaidukov later noted that the most imaginative narratives were typical of the 1980s, and that more realistic narratives were gaining ground in the twenty-first century.[70]

The Book of Veles

.jpg.webp)

Many Rodnovers regard the Book of Veles as a holy text,[73] and as a genuine historical document,[74] or as a document that despite being a literary invention has conveyed traditional truth.[72] Its composition is attributed by Rodnovers to ninth- or early tenth-century Slavic priests who wrote it in Polesia or the Volyn region of modern north-west Ukraine. Russian interpreters, however, locate this event much further east and north. The Book contains hymns and prayers, sermons, mythological, theological and political tracts, and historical narrative. It tells the wandering, over about one thousand and five hundred years of the ancestors of the Rus', identified as the Oryans (the book's version of the word "Aryan"), between the Indian subcontinent and the Carpathian Mountains, with modern Ukraine ultimately becoming their main homeland. The scholar Adrian Ivakhiv said that this territorial expansiveness is the main issue that makes historians wary of the Book.[75] Aitamurto described the work as a "Romantic description" of a "Pagan Golden Age".[68]

The fact that scholars outspokenly characterize the Book as a modern, twentieth-century composition has added to the allure that the text has for many Slavic Native Faith practitioners. According to them, such criticism is an attempt to "suppress knowledge" carried forward either by Soviet-style scientism or by "Judaic cosmopolitan" forces. A number of Ukrainian scholars defend the truthfulness of the Book, including literary historian Borys Yatsenko, archaeologist Yury Shylov, and writers Valery Shevchuk, Serhy Plachynda, Ivan Bilyk, and Yury Kanyhin. These scholars claim that criticism of the Book primarily comes from Russians interested in promoting a Russocentric view of history which sets the origin of all East Slavs in the north, while the Book shows that southern Rus' civilisation is much older, and nearer to Ukrainians themselves, West Slavs, South Slavs and the eastern Indo-European composers of the Vedas, than to Russians.[75] For many Ukrainian Rodnovers, the Book provides them with a cosmology, ethical system, and ritual practices that they can follow, and confirms their belief that the ancient Ukrainians had a literate and advanced civilisation prior to the arrival of Christianity.[73] Other modern literary works that have influenced the movement, albeit on a smaller scale, include The Songs of the Bird Gamayon, Koliada's Book of Stars, The Song of the Victory on Jewish Khazaria by Sviatoslav the Brave or The Rigveda of Kiev.[76]

Aryans and polar mysticism

Some Rodnovers believe that the Slavs are a race distinct from other ethnic groups.[32] According to them, the Slavs are the directest descendants of ancient Aryans, whom they equate with the Proto-Indo-Europeans.[77] Some Rodnovers espouse esoteric teachings which hold that these Aryans have spiritual origins linked to astral patterns of the north celestial pole (the circumpolar stars), around the pole star, the Great Bear and the Great Chariot, or otherwise to the Orion constellation.[32] According to these teachings the Aryans originally dwelt at the geographic North Pole, where they lived until the weather changed and they moved southwards, settling in Russia's southern steppes and from there spreading throughout Eurasia.[78] The northern homeland was the Hyperborea, and it was the terrestrial reflection of the celestial world of the gods; the North Pole is held to be the point of grounding of the spiritual flow of good forces coming from the north celestial pole, while the South Pole is held to be the lowest point of materialisation where evil forces originate.[79]

Other Rodnovers emphasise that the Aryans germinated in Russia's southern steppes.[80] In claiming an Aryan ancestry, Slavic Native Faith practitioners legitimise their cultural borrowing from other ethnic groups whom they claim are also Aryan descendants, such as the Germanic peoples or those of the Indian subcontinent.[81] Another belief held by some Rodnovers is that many ancient societies—including those of the Egyptians, Hittites, Sumerians, and Etruscans—were created by Slavs, but that this has been concealed by Western scholars eager to deny the Slavic peoples knowledge of their true history.[80]

Eschatology

Rodnovery has a "cyclical-linear model of time", in which the cyclical and the linear morphologies do not exclude each other, but complement each other and stimulate eschatological sentiments.[82] Such morphology of time is otherwise describable as "spiral".[83] The Rodnover movement claims to solve the fundamental problems of the modern world either by returning to the lifestyle and life-meaning attitudes of the ancestors (retro-utopia), or by radically restructuring the existing world order, building a new world on the principles of a renewed primordial tradition (archeofuturism). As the archaic is based on the recognition of eternity, stability and immutability of the cosmic order, which cyclically dies but then revives in its original form, eschatological themes are clearly present within Rodnovery.[66] Archaic patterns of meaning re-emerge at different levels on the spiral of time.[83] The movement proposes itself as a return to a "Golden Age", being the current historical period one of "widespread experience [...] of tragic breakdown and collapse", of "the meaninglessness and prospects of world civilisation" which has "entered an irrevocable dead end", its "last time".[84]

Three morphologies of Rodnover eschatology have been observed; gnosiological, apocalyptic, and cosmological: the first, proposed by S. M. Telegin in his 2014 book The Rise of Myth, tells of a general awakening of the consciousness of mankind, of a "coming revolt of the healthy natural principle rooted in mankind against the Christian religion and the technocratic civilisation generated by it", a reawakening of the gods in men and therefore the re-establishment of mankind's dominance over the cosmos;[85] the second, expounded in the Slavo-Aryan Vedas of Ynglism, is apocalyptic, telling about a series of coming events and the end of the world determined by higher powers and independent from human will;[86] the third, based on the cosmology elaborated by N. V. Levashov (1961–2012), Levashovism, tells that there are so-called "Days of Svarog" (periods of harmony and evolution influenced by Bright Forces) and "Nights of Svarog" (periods of disorder and degeneration influenced by Dark Forces) in both time and space, and they are determined by different balances of the "seven primary matters" of which everything is made, in turn determined by the movements of the Solar System in the Milky Way galaxy.[87]

Besides these morphologies, volkhv Veleslav (Ilya G. Cherkasov) proposed the prophecy of a return of Ariy or Oriy, "the ancestor and cultural hero of all Aryans [...] riding a winged white horse, holding the Sword of Law [...] to restore the violated Laws of Svarog".[88] Volkhv Dobroslav proposed what has been described as a "social eschatology" or an "anthropological eschatology", in which the apocalyptic "end of the world" is the natural and irreversible final phase of the degeneration of the Western, Christian historical and cultural community, which is doomed to death and will make space for a renewed humanity harmonised to genealogical principles.[89] Another distinctive perspective is that of Vseyasvetnaya Gramota, whose eschatology holds that the degeneration of society is due to the distortion of language, its detachment from reality, from the "fundamental principles" of the divine order, and from God itself.[90]

Some Rodnovers believe that Russia has a messianic role to play in human history and eschatology; Russia would be destined to be the final battleground between good and evil or the centre of a post-apocalyptic civilisation which will survive the demise of the Western world.[9] At this point—they believe—the entire Russian nation will embrace Rodnovery.[91] The Russian Rodnover leader Aleksandr Asov promoted the Book of Veles as the "geopolitical weapon of the next millennium" through which an imperial, Eurasian Russia will take over the spiritual and political leadership of the world from the degenerated West.[75] Other Rodnovers believe that the new spiritual geopolitical centre will be Ukraine.[92]

Sociology

Political influence

In 2006, a conference of the European New Right was held in Moscow under the title "The Future of the White World", with participants including Rodnover leaders such as Ukraine's Halyna Lozko and Russia's Pavel Tulaev. The conference focused on ideas for the establishment in Russia of a political entity that would function as a new epicentre of white race and civilisation, enshrining the "religion, philosophy, science and art" that emanate from the "Aryan soul",[93] either taking the form of Guillaume Faye's "Euro-Siberia", Aleksandr Dugin's "Eurasia", or Pavel Tulaev's "Euro-Russia".[94] According to Tulaev, Russia enshrines in its own name the essence of the Aryans, one of the etymologies of Rus being from a root that means "bright", whence "white" in mind and body.[95]

Rodnover ideas and symbols have also been adopted by many Russian nationalists—including in the Russian skinhead movement[96]—not all of whom embrace Rodnovery as a religion.[97] Some of these far-right groups merge Rodnover elements with others adopted from Germanic Heathenry and from Russian Orthodox Christianity.[98] Ynglism was characterised by Aitamurto as less politically goal-oriented than other Rodnover movements,[99] while in 2001 Vladimir B. Yashin of the Department of Theology and World Cultures of Omsk State University found that Ynglism had close ties with the regional branch of the far-right Russian National Unity of Alexander Barkashov, whose members provided security and order during the mass gatherings of the Ynglists.[100] A number of young practitioners of Slavic Native Faith have been detained on terrorism charges in Russia;[33] between 2008 and 2009, teenaged Rodnovers forming a group called the Slavic Separatists conducted at least ten murders and planted bombs across Moscow targeting Muslims and non-ethnic Russians.[101]

In 2012 the adherents of Anastasianism were expecting a law in Russia according to which everyone might get one hectare of land for free, in order to facilitate the realisation of their ideal society in which every kin should have its land where to develop itself and its offspring.[102] Although in principle Anastasians refute the very idea of party politics, by 2016 some of them had founded the "Native Party" (Родная партия, Rodnaya partiya), which was registered by the Russian Ministry of Justice, and proposed a bill "About kinship homesteads" (О родовых поместьях, O rodovykh pomest'yakh), supported by the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia and by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation (which drafted their own versions of the bill).[103] On 1 May 2016, the president Vladimir Putin enacted the Law on the Far Eastern Hectare.[104]

Academic support

Although Rodnover historiosophy is typically rooted in spiritual conviction rather than in arguments that would be acceptable within contemporary Western scientific paradigms, many Rodnovers seek to promote their beliefs about the past within the academia.[70] For instance, in 2002 Serbian practitioners established Svevlad, a research group devoted to historical Slavic religion which simulated academic discourse but was "highly selective, unsystematic, and distorted" in its examination of the evidence.[105] In Poland, archaeologists and historians have been hesitant about any contribution that Rodnovers can make to understandings of the past.[106] Similarly, in Russia, many of the larger and more notable universities refuse to give a platform to Rodnover views, but smaller, provincial institutions have sometimes done so.[70]

Within Russia, there are academic circles in which a "very vivid trend of alternative history" is promoted; these circles share many of the views of Slavic Native Faith adherents, particularly regarding the existence of an advanced, ancient Aryan race from whom ethnic Russians are descended.[107] For instance, Gennady Zdanovich, the discoverer of Arkaim (an ancient Proto-Indo-European site) and leading scholar about it and broader Sintashta culture, is a supporter of the views of the history of the Aryans that are popular within Rodnovery and is noted for his spiritual teachings about how sites like Arkaim were ingenious "models of the universe". For this, Zdanovich was criticised by publications of the Russian Orthodox diocese of Chelyabinsk, especially in the person of colleague archaeologist Fedor Petrov, who "begs the Lord to forgive" for the corroboration that archaeology has provided to the Rodnover movement.[108]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Aitamurto 2016, p. 141.

- ↑ Simpson & Filip 2013, p. 39; Shnirelman 2017, p. 90.

- ↑ Yashin 2016, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Saunders 2019, p. 566.

- 1 2 Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 235; Aitamurto 2008, p. 6.

- 1 2 Shnirelman 2013, p. 63.

- 1 2 Laruelle 2012, p. 308.

- 1 2 Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 223.

- 1 2 Aitamurto 2006, p. 189.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2008, pp. 2–5.

- 1 2 Aitamurto 2016, p. 114.

- ↑ Laruelle 2012, p. 296.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 205.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2013, p. 63; Aitamurto 2016, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2016, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Simpson & Filip 2013, p. 39.

- ↑ Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 211; Lesiv 2017, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 211.

- ↑ Eliade, Mircea (1958). Patterns in Comparative Religion. pp. 60 ff.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2012.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2008, pp. 2–3.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2008, p. 3.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2008, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Andreeva 2012, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2008, p. 5.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2008, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Andreeva 2012, p. 118.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2008, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Simpson 2013, p. 118.

- ↑ Črnič 2013, p. 189.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 195; Lesiv 2013b, p. 131.

- 1 2 3 Aitamurto 2006, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 Shnirelman 2013, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 Shnirelman 2013, p. 72.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, pp. 201–202.

- ↑ Prokofiev, Filatov & Koskello 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 229.

- ↑ Laruelle 2012, p. 307.

- ↑ Ivakhiv 2005b, pp. 225–226.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 206.

- 1 2 Aitamurto 2016, p. 88; Golovneva 2018, p. 343.

- 1 2 Aitamurto 2006, p. 190.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 185.

- 1 2 Aitamurto 2006, p. 190; Shlyapentokh 2014, pp. 77–79.

- 1 2 Shnirelman 2013, p. 62.

- ↑ Laruelle 2008, p. 296.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 197.

- 1 2 Shlyapentokh 2014, p. 77.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2000, p. 18; Shnirelman 2013, p. 66.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2016, p. 32.

- ↑ Pilkington & Popov 2009, p. 273.

- ↑ Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 234; Laruelle 2008, p. 284.

- ↑ Shlyapentokh 2014, pp. 77–79.

- ↑ Shlyapentokh 2014, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 234.

- ↑ Simpson 2017, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Shlyapentokh 2014, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Shnirelman 1998, passim; Shnirelman 2007, p. 58.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2013, p. 62; Shizhenskii & Aitamurto 2017, p. 114.

- ↑ Simpson 2017, p. 71.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 201.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 202.

- ↑ Shizhenskii & Aitamurto 2017, p. 129.

- ↑ Ozhiganova 2015, p. 33.

- ↑ Lesiv 2013a, p. 93.

- 1 2 Yashin 2016, p. 36.

- ↑ Lesiv 2013b, p. 137.

- 1 2 Aitamurto 2006, p. 186.

- ↑ Dulov 2013, p. 206.

- 1 2 3 Aitamurto & Gaidukov 2013, p. 155.

- ↑ "Дощьки" [The Planks]. Жар-Птица [Firebird]. San Francisco. January 1954. pp. 11–16.

- 1 2 Prokofiev, Filatov & Koskello 2006, p. 189.

- 1 2 Ivakhiv 2005b, p. 219.

- ↑ Laruelle 2008, p. 285.

- 1 2 3 Ivakhiv 2005a, p. 13.

- ↑ Laruelle 2008, p. 291.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2017, p. 90.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2006, p. 187; Laruelle 2008, p. 292.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2000, p. 29.

- 1 2 Laruelle 2008, p. 292.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2017, p. 103.

- ↑ Yashin 2016, pp. 37–38.

- 1 2 Tyutina 2015, p. 45.

- ↑ Yashin 2016, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Yashin 2016, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Yashin 2016, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Yashin 2016, p. 40.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2007, p. 54; Yashin 2016, p. 38.

- ↑ Tyutina 2015, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Povstyeva 2020, p. 48.

- ↑ Laruelle 2008, p. 29.

- ↑ Ivakhiv 2005a, p. 15.

- ↑ Arnold & Romanova 2013, pp. 90–91.

- ↑ Arnold & Romanova 2013, p. 84–85.

- ↑ Arnold & Romanova 2013, p. 86.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2013, p. 67; Shizhenskii & Aitamurto 2017, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Aitamurto & Gaidukov 2013, p. 156.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2013, p. 68.

- ↑ Aitamurto 2016, p. 51.

- ↑ Maltsev, V. A. (18 November 2015). "Расизм во имя Перуна поставили вне закона". Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Archived from the original on 30 April 2020.

- ↑ Shnirelman 2013, p. 70; Skrylnikov 2016, passim.

- ↑ Andreeva 2012, p. 116, note 1.

- ↑ Pozanenko 2016, p. 148.

- ↑ "Far Eastern Hectare". Ministry for the Development of the Russian Far East and Arctic.

- ↑ Radulovic 2017, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Simpson 2013, p. 120.

- ↑ Laruelle 2008, p. 295.

- ↑ Petrov, Fedor (29 June 2010). "Наука и неоязычество на Аркаиме (Science and Neopaganism at Arkaim)". Proza.ru. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

Sources

- Aitamurto, Kaarina (2006). "Russian Paganism and the Issue of Nationalism: A Case Study of the Circle of Pagan Tradition". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 8 (2): 184–210. doi:10.1558/pome.8.2.184.

- ——— (2008). "Egalitarian Utopias and Conservative Politics: Veche as a Societal Ideal within Rodnoverie Movement". Axis Mundi: Slovak Journal for the Study of Religions. 3: 2–11.

- ——— (2016). Paganism, Traditionalism, Nationalism: Narratives of Russian Rodnoverie. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781472460271.

- Aitamurto, Kaarina; Gaidukov, Alexey (2013). "Russian Rodnoverie: Six Portraits of a Movement". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 146–163. ISBN 9781844656622.

- Andreeva, Julia Olegovna (2012). "Вопросы власти и самоуправления в религиозном движении 'Анастасия': идеальные образы родовых поселений и 'Воплощение мечты'" [Questions of power and self-government in the religious movement 'Anastasia': Ideal images of ancestral settlements and 'Dreams coming true']. Anthropological Forum (in Russian). Saint Petersburg: Kunstkamera; European University at Saint Petersburg. 17. ISSN 1815-8870.

- Arnold, Richard; Romanova, Ekaterina (2013). "The White World's Future: An Analysis of the Russian Far Right". Journal for the Study of Radicalism. 7 (1): 79–108. doi:10.1353/jsr.2013.0002. ISSN 1930-1189. S2CID 144937517.

- Črnič, Aleš (2013). "Neopaganism in Slovenia". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 182–194. ISBN 9781844656622.

- Dulov, Vladimir (2013). "Bulgarian Society and Diversity of Pagan and Neopagan Themes". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 195–212. ISBN 9781844656622.

- Golovneva, Elena (2018). "Saving the Native Faith: Religious Nationalism in Slavic Neo-paganism (Ancient Russian Yngling Church of Orthodox Old Believers-Ynglings and Svarozhichi)". In Stepanova, Elena; Kruglova, Tatiana (eds.). Convention 2017 "Modernization and Multiple Modernities". Yekaterinburg: Knowledge E. pp. 337–347. doi:10.18502/kss.v3i7.2485. ISSN 2518-668X. S2CID 56439094.

- Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005a). "In Search of Deeper Identities: Neopaganism and 'Native Faith' in Contemporary Ukraine" (PDF). Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. 8 (3): 7–38. doi:10.1525/nr.2005.8.3.7. JSTOR 10.1525/nr.2005.8.3.7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2020.

- ——— (2005b). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 209–239. ISBN 9781851096084.

- Laruelle, Marlène (2008). "Alternative Identity, Alternative Religion? Neo-Paganism and the Aryan Myth in Contemporary Russia". Nations and Nationalism. 14 (2): 283–301. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8129.2008.00329.x.

- ——— (2012). "The Rodnoverie Movement: The Search for Pre-Christian Ancestry and the Occult". In Brigit Menzel; Michael Hagemeister; Bernice Glatzer Rosenthal (eds.). The New Age of Russia: Occult and Esoteric Dimensions. Kubon & Sagner. pp. 293–310. ISBN 9783866881976.

- Lesiv, Mariya (2013a). The Return of Ancestral Gods: Modern Ukrainian Paganism as an Alternative Vision for a Nation. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773542624.

- ——— (2013b). "Ukrainian Paganism and Syncretism: 'This Is Indeed Ours!'". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 128–145. ISBN 9781844656622.

- ——— (2017). "Blood Brothers or Blood Enemies: Ukrainian Pagans' Beliefs and Responses to the Ukraine-Russia Crisis". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 133–156. ISBN 9781137570406.

- Ozhiganova, Anna (2015). "Конструирование традиции в неоязыческой общине 'ПравоВеди'" [Construction of tradition in the Neopagan community 'PravoVedi']. Colloquium Heptaplomeres (in Russian). Nizhny Novgorod: Minin University. II: 30–38. ISSN 2312-1696.

- Pilkington, Hilary; Popov, Anton (2009). "Understanding Neo-paganism in Russia: Religion? Ideology? Philosophy? Fantasy?". In George McKay (ed.). Subcultures and New Religious Movements in Russia and East-Central Europe. Peter Lang. pp. 253–304. ISBN 9783039119219.

- Povstyeva, Karina Yurievna (2020). Esoteric Appropriation of Classical Russian Literary Texts (Thesis) (in Russian). Moscow: Higher School of Economics.

- Pozanenko, Artemy Alekseyevich (2016). "Самоизолирующиеся сообщества. Социальная структура поселений родовых поместий" [Self-isolating communities. The social structure of the settlements of ancestral estates]. Universe of Russia (in Russian). Moscow: Higher School of Economics. 25 (1): 129–153. ISSN 1811-038X.

- Prokofiev, A.; Filatov, S.; Koskello, A. (2006). "Славянское и скандинавское язычества. Викканство" [Slavic and Scandinavian Paganism, and Wiccanism]. In Bourdeaux, Michael; Filatov, Sergey (eds.). Современная религиозная жизнь России. Опыт систематического описания [Contemporary religious life of Russia. Systematic description of experiences] (in Russian). Vol. 4. Moscow: Keston Institute; Logos. pp. 155–207. ISBN 5987040574.

- Radulovic, Nemanja (2017). "From Folklore to Esotericism and Back: Neo-Paganism in Serbia". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 19 (1): 47–76. doi:10.1558/pome.30374.

- Saunders, Robert A. (2019). "Rodnovery". Historical Dictionary of the Russian Federation (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 565–567. ISBN 9781538120484.

- Shizhenskii, Roman; Aitamurto, Kaarina (2017). "Multiple Nationalisms and Patriotisms among Russian Rodnovers". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 109–132. ISBN 9781137570406.

- Shlyapentokh, Dmitry (2014). "Антисемитизм истории: вариант русских неоязычников" [The antisemitism of history: The case of Russian Neopagans]. Colloquium Heptaplomeres (in Russian). Nizhny Novgorod: Minin University. I: 76–85. ISSN 2312-1696.

- Shnirelman, Victor A. (1998). Russian Neo-pagan Myths and Antisemitism (PDF). Analysis of Current Trends in Antisemitism, Acta no. 13. Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism, Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2021.

- ——— (2000). "Perun, Svarog and Others: Russian Neo-Paganism in Search of Itself". The Cambridge Journal of Anthropology. 21 (3): 18–36. JSTOR 23818709.

- ——— (2007). "Ancestral Wisdom and Ethnic Nationalism: A View from Eastern Europe". The Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies. 9 (1): 41–61. doi:10.1558/pome.v9i1.41.

- ——— (2012). "Русское Родноверие: Неоязычество и Национализм в Современной России" [Russian Native Faith: Neopaganism and nationalism in modern Russia]. Russian Journal of Communication (in Russian). 5 (3): 316–318. doi:10.1080/19409419.2013.825223. S2CID 161875837.

- ——— (2013). "Russian Neopaganism: From Ethnic Religion to Racial Violence". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 62–71. ISBN 9781844656622.

- ——— (2015). "Perun vs Jesus Christ: Communism and the emergence of Neo-paganism in the USSR". In Ngo, T.; Quijada, J. (eds.). Atheist Secularism and its Discontents. A Comparative Study of Religion and Communism in Eurasia. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 173–189. ISBN 9781137438386.

- ——— (2017). "Obsessed with Culture: The Cultural Impetus of Russian Neo-Pagans". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 87–108. ISBN 9781137570406.

- Simpson, Scott (2013). "Polish Rodzimowierstwo: Strategies for (Re)constructing a Movement". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 112–127. ISBN 9781844656622.

- ——— (2017). "Only Slavic Gods: Nativeness in Polish Rodzimowierstwo". In Kathryn Rountree (ed.). Cosmopolitanism, Nationalism, and Modern Paganism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 65–86. ISBN 9781137570406.

- Simpson, Scott; Filip, Mariusz (2013). "Selected Words for Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe". In Kaarina Aitamurto; Scott Simpson (eds.). Modern Pagan and Native Faith Movements in Central and Eastern Europe. Durham: Acumen. pp. 27–43. ISBN 9781844656622.

- Skrylnikov, Pavel (20 July 2016). "The Church Against Neo-Paganism". Intersection. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017.

- Tyutina, Olga Sergeyevna (2015). "Эсхатологический компонент в современном славянском язычестве на примере концепции истории А. А. Добровольского" [The eschatological component in modern Slavic Paganism on the example of A. A. Dobrovolsky's concept of history]. Colloquium Heptaplomeres (in Russian). Nizhny Novgorod: Minin University. II: 44–47. ISSN 2312-1696.

- Yashin, Vladimir Borisovich (2016). "Эсхатологические мотивы в современном русском неоязычестве" [Eschatological motifs in modern Russian Neopaganism]. Colloquium Heptaplomeres (in Russian). Nizhny Novgorod: Minin University. III: 36–42. ISSN 2312-1696.