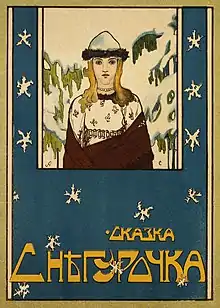

Snegurochka (diminutive) or Snegurka (Russian: Снегу́рочка (diminutive), Снегу́рка, IPA: [sʲnʲɪˈgurətɕkə, snʲɪˈgurkə]), or The Snow Maiden, is a character in Russian fairy tales.

This character has no apparent roots in traditional Slavic mythology and customs, having made its first appearance in Russian folklore in the 19th century.[1]

Since the mid-20th century under the Soviet period, Snegurochka has also been depicted as the granddaughter and helper of Ded Moroz during New Year parties for children.[1]

Classification

Tales of the Snegurochka type are Aarne–Thompson type 703* The Snow Maiden.[2] The Snegurochka story compares to tales of type 1362, The Snow-child, where the strange origin is a blatant lie.[3]

Folk tale versions and adaptations

A version of a folk tale about a girl made of snow and named Snegurka (Snezhevinochka; Снегурка (Снежевиночка)) was published in 1869 by Alexander Afanasyev in the second volume of his work The Poetic Outlook on Nature by the Slavs, where he also mentions the German analog, Schneekind ("Snow Child"). In this version, childless Russian peasants Ivan and Marya made a snow doll, which came to life. This version was later included by Louis Léger in Contes Populaires Slaves (1882).[4] Snegurka grows up quickly. A group of girls invite her for a walk in the woods, after which they make a small fire and take turns leaping over it; in some variants, this is on St. John's Day, and a St. John's Day tradition. When Snegurka's turn comes, she starts to jump, but only gets halfway before evaporating into a small cloud. Andrew Lang included this version as "Snowflake" in The Pink Fairy Book (1897).[4]

In another story, she is the daughter of Spring the Beauty (Весна-Красна) and Ded Moroz, and yearns for the companionship of mortal humans. She grows to like a shepherd named Lel, but her heart is unable to know love. Her mother takes pity and gives her this ability, but as soon as she falls in love, her heart warms and she melts. This version of the story was made into a play The Snow Maiden by Aleksandr Ostrovsky, with incidental music by Tchaikovsky in 1873.

In 1878, the composer Ludwig Minkus and the Balletmaster Marius Petipa staged a ballet adaptation of Snegurochka titled The Daughter of the Snows for the Tsar's Imperial Ballet. The tale was also adapted into an opera by Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov titled The Snow Maiden: A Spring Fairy Tale (1880–81).

The story of Snegurochka was adapted into two Soviet films: an animated film with some of Rimsky-Korsakov's music, called The Snow Maiden (1952), and the live-action film The Snow Maiden (1968).. Ruth Sanderson retold the story in the picture book The Snow Princess, in which falling in love does not immediately kill the princess, but turns her into a mortal human, who will die.

In February 2012, the Slovenian poet Svetlana Makarovič published a ballad fairy tale, titled Sneguročka ("Snegurochka"), which was inspired by the Russian fairy tale character. Makarovič has had great passion for Russian tradition since childhood.[5]

Artist and author Jonathon Keats's short story "Ardour" is a modern adaptation of this fairy tale, featured in Kate Bernheimer's 2010 anthology of contemporary tales based on classic archetypes, My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me.[6]

Granddaughter of Ded Moroz

In the late Russian Empire Snegurochka was part of Christmas celebrations, in the form of figurines to decorate the fir tree and as a character in children's pieces.[1] In the early Soviet Union, the holiday of Christmas was banned, together with other Christian traditions, until it was reinstated as a holiday of newly-independent Russia in 1991.[7] However, in 1935 the celebration of the New Year was allowed, which included, in part, the fir tree and Ded Moroz. At this time Snegurochka acquired a role of the granddaughter of Ded Moroz and his helper.[1][8] In this role, she wears long silver-blue robes and a furry cap[9] or a snowflake-like kokoshnik. During the usual scripts of Christmas celebrations, Snegurochka's appearance is usually accompanied by the audience waiting for her and screaming "Sne-gu-roch-ka".[10][11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Душечкина Е. В. (2003). "Дед Мороз и Снегурочка". Отечественные записки. No. 1.

- ↑ D. L. Ashliman, The Snow Maiden: folktales of type 703*

- ↑ D. L. Ashliman, The Snow Child: folktales of type 1362

- 1 2 Andrew Lang, The Pink Fairy Book, "Snowflake"

- ↑ "Svetlana Makarovič o temni lepoti, ki se rodi iz gorja" [Svetlana Makarovič About a Dark Beauty, Which is Born from Woe] (in Slovenian). MMC RTV Slovenia. 16 February 2012.

- ↑ Kate Bernheimer (28 September 2010). My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me: Forty New Fairy Tales. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-46438-0.

- ↑ Sudskov, Dmitry (12 December 2007). "Christmas had to survive dark years of communism to return to Russia". PRAVDA. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ↑ "Who were Snegurochka's parents?". postnauka.ru (in Russian). Post-Science. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ↑ "Snegurochka: The Snow Maiden in Russian Culture by Kerry Kubilius". About.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-24. Retrieved 2010-11-26.

- ↑ "Why does Ded Moroz always come by himself, and Snegurochka must be called, and more than once?". otvet.mail.ru (in Russian). 4 January 2009. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ↑ "Мадонна обратилась к российским фанам" [Madonna addressed the Russian fans] (in Russian). Komsomolskaya Pravda. 13 September 2006. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

The tribunes chanted: "Sne-gu-roch-ka! Come out!" Snegurochka came out with a whip and a hat

External links

- Snowflake, Lang's version