The Soim (Ukrainian: Сойм Карпатської України) was the parliament of the short-lived Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine.[1] The assembly had its seat in Khust.[1]

Background

The establishment of a Soim, an autonomous parliament for the Ruthenian region, had been stipulated in the 11th article of the 1919 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye.[2] But the establishment of the autonomous parliament was delayed for many years.[2]

Election

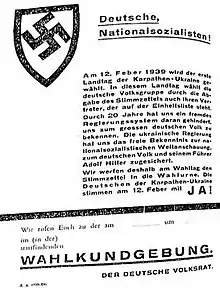

After years of delays, election to the Soim was held on 12 February 1939 on the basis of the passing of legislation by the Czechoslovak parliament providing further autonomy for Carpatho-Ukraine on 22 November 1938.[1] 32 members of the Soim were elected from a single constituency.[1] The Ukrainian National Union (UNO) presented a unity list for the vote.[1] According to results published, 244,922 out of 265,002 votes cast (92%) went in favour of the unity list.[3]

Out of the 32 members elected there were 29 Ukrainians, 1 Czech, 1 German and 1 Romanian.[1] The German deputy was Anton Ernst Oldofredi, leader of the German People's Council (Deutsche VolksRat, DVR).[1]

The elected candidates were:[4][5]

| Name | Village | Office/Profession | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dr. Avgustyn Voloshyn | Khust | Premier of the Government of Carpatho-Ukraine |

| 2 | Yulian Revay | Khust | Minister of the Government of Carpatho-Ukraine |

| 3 | Dr. Mychailo Briaschayko | Khust | notary public |

| 4 | Dr. Julius Briaschayko | Khust | attorney |

| 5 | Ivan Gryga | Vyshni Verets'ky | farmer |

| 6 | Rev. Adalbert Dovbak | Izky | Priest |

| 7 | Dr. Mykola Dolynay | Khust | Hospital Director of the hospital, Khust |

| 8 | Dr. Milosh Drbal | Khust | attorney |

| 9 | Augustine Dutka | Khust | Judge |

| 10 | Ivan Ihnatko | Bilky | farmer |

| 11 | Dr. Volodymyr Komarynsky | Khust | Head of Press Department |

| 12 | Ivan Kachala | Perechyn | railroad engineer |

| 13 | Vasyl' Klempush | Yasinya | businessman, Yasinya |

| 14 | Stepan Klochurak | Khust | Secretary to the Prime Minister |

| 15 | Vasyl' Latsanych | Velykyy Bereznyy | teacher |

| 16 | Mykola Mandzyuk | Sevlyush | teacher |

| 17 | Mykhaylo Marushchak | Velykyy Bychkiv | farmer |

| 18 | Leonid Romanyuk | Khust | engineer |

| 19 | Rev. Grigorie Moysh | Bila Tserkov | protopop |

| 20 | Dmytro Nimchuk | Khust | President of the Public Health Insurance Institution |

| 21 | Anton Ernst Oldofredi | Khust | Under Secretary of State |

| 22 | Yuriy Pazukhanych | Khust | school inspector |

| 23 | Ivan Perevuznyk | Serednye | farmer |

| 24 | Petro Popovych | Velyki Luchky | farmer |

| 25 | Fedir Revay | Khust | Director of the State Printing House |

| 26 | Dr. Mykola Risdorfer | Svalyava | physician |

| 27 | Dr. Stefan Roscha | Khust | Ministry of Education officia |

| 28 | Rev. Yuriy Stanynets' | Vonihovo | pastor |

| 29 | Vasyl' Shobey | Vul'khivtsi | farmer |

| 30 | Avhustyn Shtefan | Khust | Chief of the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs |

| 31 | Rev. Fedelesh | Khust | Professor of Religion |

| 32 | Mykhaylo Tulyk | Khust | journalist |

Session

The Soim met once on 15 March 1939.[1][6] The inaugural session had been scheduled for 2 March 1939 but the Czecho-Slovak president Emil Hácha opted not to convene the assembly.[7] In response to the Slovak declaration of independence on 14 March 1939, the regional government of Avgustyn Voloshyn called for an independent Carpatho-Ukrainian state under the protection of the German Reich.[6]

Whilst the session was in progress the time Hungarian troops were on the offensive in Carpatho-Ukraine and Czecho-Slovak forces were retreating westward.[8] Augustin Stefan served as the speaker of the assembly.[9] Stefan Roscha served as the vice speaker of the assembly.[10]

The assembly, with 22 members present, declared the independence of the Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine.[1] The session ratified the constitution of the Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine, with Ukrainian as the official language and a presidential form of governance.[11] The Soim elected Voloshyn as President of the Republic.[9][11] Yulian Revay was named Prime Minister.[11]

Khust was attacked by Hungarian forces on the same day as the session was held.[8] Carpatho-Ukraine was annexed by Hungary the following day, ending the brief existence of the Republic of Carpatho-Ukraine.[1]

Tragedy of Carpatho-Ukraine

The Soim session is depicted in the 1940 movie Tragedy of Carpatho-Ukraine, produced by Vasyl Avramenko.[12]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Mads Ole Balling (1991). Von Reval bis Bukarest: Ungarn, Jugoslawien, Rumänien, Slowakei, Karpatenukraine, Kroatien, Memelländischer Landtag, Schlesischer Landtag, komparative Analyse, Quellen und Literatur, Register (in German). Dokumentation Verlag. pp. 671, 673. ISBN 978-87-983829-5-9.

- 1 2 Aldo Dami (1936). Destin des minorités. Sorlont. p. 182.

- ↑ Opinion: Official Publication of Ukrainian Canadian Veterans' Association. Vol. 3–5. UCVA. 1947. p. 79.

- ↑ The Trident. Vol. 3–4. Published by Organization for Rebirth of Ukraine. 1939. pp. 12, 22.

- ↑ Peter George Stercho (1971). Diplomacy of Double Morality: Europe's Crossroads in Carpatho-Ukraine, 1919-1939. Carpathian Research Center. p. 408.

- 1 2 Stephen Denis Kertesz (1974). Diplomacy in a Whirlpool: Hungary Between Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia. Greenwood Press. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-8371-7540-9.

- ↑ Volodymyr Kubiĭovych (1963). Ukraine, a Concise Encyclopedia. Ukrainian National Association. p. 855.

- 1 2 Paul R. Magocsi (1996). A History of Ukraine. University of Toronto Press. p. 615. ISBN 978-0-8020-7820-9.

- 1 2 The Ukrainian Quarterly. Vol. 34–35. Ukrainian Congress Committee of America. 1978. p. 412.

- ↑ Paul R. Magocsi (1973). An Historiographical Guide to Subcarpathian Rusʹ. Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute, Harvard University. p. 247.

- 1 2 3 Ivan Katchanovski; Zenon E. Kohut; Bohdan Y. Nebesio; Myroslav Yurkevich (11 July 2013). Historical Dictionary of Ukraine. Scarecrow Press. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8108-7847-1.

- ↑ Alan Gevinson (1997). Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911–1960. University of California Press. pp. 1060–1061. ISBN 978-0-520-20964-0.

.png.webp)