| Somosaguas paleontological site | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Middle Aragonian (≈Langhian-Serravallian). | |

Somosaguas Norte paleontological site, located in the Somosaguas campus of the Complutense University, next to the Faculty of Political Science and Sociology and the Faculty of Social Work. | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Location | |

| Location | Madrid, Spain |

| Coordinates | 40°25′51″N 3°47′19″W / 40.430833°N 3.788556°W |

| Region | Southern Plateau of the Iberian Peninsula |

| Country | Spain |

The Somosaguas fossil site is located in the Community of Madrid, in the Somosaguas campus, within the municipality of Pozuelo de Alarcón (Spain).[1] The fossils found belong to the fauna of the Aragonian continental stage (middle Miocene), about 14 million years ago.[1] The sediments where the remains are found were deposited in an alluvial fan sedimentary environment.[2] The site itself is formed by two zones with fossil presence, separated by 60 m (200 ft): Somosaguas Norte, which occupies an upper stratigraphic position, and Somosaguas Sur.[3]

The site was discovered in 1989 by a geology student near the Faculty of Political Sciences of the Complutense University, when he observed bone fragments in the ground.[4][5] The student reported the discovery to Professor Nieves López Martínez, who verified that the remains were fossils, and in turn reported it to the Department of Paleobiology of the Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales.[4]

History

In 1989 a geology student at the Complutense University of Madrid, Francisco Hernández Arteaga, was waiting for his girlfriend next to the Faculty of Political Science at the Somosaguas campus when he discovered skeletal remains on the ground.[4][5][2] He did not report the discovery until 1996.[2] Once the discovery was reported, members of the Paleobiology Department of the National Museum of Natural Sciences carried out prospections in the area, the results of which were included in a report presented to the Ministry of Culture of the Community of Madrid, and the site was included in the paleontological chart.[3] The first paleontological excavation took place in 1998, in which Professor Nieves López led a team of students from the Faculty of Geological Sciences of Madrid, with the financial support of the Rector's Office of the Complutense University, and with the collaboration of the National Museum of Natural Sciences.[2]

Since then, excavations have been carried out regularly by students and since 2000 a fortnightly work period has been established in April or May, in addition to open days, workshops and exhibitions.[6]

Geology

The site is located on Miocene materials that were deposited by a system of alluvial fans, which were formed due to the erosion suffered by the granitic and metamorphic rocks of the Central System.[2] These sediments outcrop from the south of the urban area of Madrid to the contact with the plutonic and metamorphic materials of the sierra.[7]

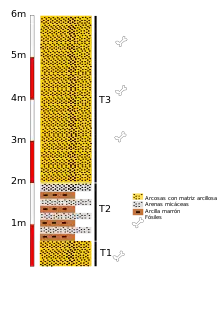

The sediments present in the deposit have a potency (sediment thickness) of 6 m and consist of arkoses with clayey matrix and rock fragments with intercalations of brown clays and micaceous sands, distinguishing three sections.[2]

- Section 1 (T1): it forms the wall of the series and is 0.5 m (1.6 ft) thick. It is formed by arkoses with a clayey matrix, and in this section of the Somosaguas Sur deposit there are a large number of micro and macrovertebrate fossils.

- Section 2 (T2): alternating levels of micaceous sands and brown clays, with a maximum thickness of 1.5 m (4.9 ft).

- Section 3 (T3): At the top of the series, it has a thickness of more than 3 m (9.8 ft), formed by arkoses with clayey matrix. The macrovertebrate fossils of Somosaguas Norte are found in this section.

Fossils

The Somosaguas Sur site has a great richness of micromammal fossils (more than 400 fossil teeth were found in 50 kg (110 lb) of sediment) that have allowed us to assign it to the Middle Aragonian E biozone (13.75–14.10 million years ago).[8][note 1] The taxa identified belong to different groups: Gliridae (Microdyromys koenigswaldi, Microdyromys monspeliensis and Armantomys tricristatus), Sciuridae (Heteroxerus grivensis and Heteroxerus rubricati), Cricetidae (Megacricetodon collongensis, Democricetodon darocensis, Cricetodon soriae and Democricetodon lacombai), Insectivora (Miosorex grivensis and Galerix exilis), Lagomorpha (Lagopsis penai and Prolagus oeningensis) and Reptilia (Chelonia, Lacertidae and Anguidae).[9] Among the macrovertebrates, remains of the mastodon Gomphotherium angustidens have been recovered; from the family Rhinocerotidae, the taxon Alicornops simorrense has been identified; from the family Equidae, remains of Anchitherium have been found; and among the ruminants, there are fossils of the genera Heteroprox (Cervidae), Micromeryx (Moschidae) and Tethytragus (Bovidae). There is also a suid, Conohyus.[10]

The fossils present in Somosaguas Norte correspond mostly to macrovertebrates, although microvertebrates have also been found, such as the lagomorphs Lagopsis and Prolagus oeningensis and the cricetid Democricetodoninae.[8] As for macrovertebrates, remains of the mastodon Gomphotherium angustidens have been documented; fossils of the carnivores Hemicyon, Amphicyon, Pseudaelurus and an undetermined mustelid;[3] the equid Anchitherium; the rhinoceros Prosantorhinus douvillei; the ruminants Heteroprox, Tethytragus and Micromeryx and the suid Conohyus simorrensis. Bird and chelonian remains have also been recovered.[8]

Taphonomy, paleoclimatology and paleoecology

Based on the taphonomic study of the Somosaguas Norte site, the following observations have been made:[11] there are a large number of splinters (small bone fragments) from two different types of bone: cancellous bone splinters and compact bone, and they seem to indicate that the bone remains have undergone intense weathering processes.[11] The presence of some fragile remains and intact surfaces has also been documented, as well as the presence of very altered remains that form powdery masses. In addition, signs of abrasion and mineral replacement have been observed in the remains.[11] It seems that the main processes that have occurred in the deposit from the taphonomic point of view are:[11]

- Presence of different thanatoceonosis with different degrees of preservation.

- Concentration of the remains.

- Compaction of the sediment during fossildiagenesis.

- Mineralization of the bones.

- Cementation, cavity filling, decalcification and decomposition of bones.

- Differential compaction causing fractures in certain remains.

Isotopic analysis of the fossil remains has shown that a cooling of the climate and an increase in aridity were taking place at that time.[12] Calculations indicate a temperature drop of 6 °C (11 °F), coinciding with the drop in temperatures recorded during the Miocene as a consequence of the re-establishment of the polar ice cap in Antarctica 14 million years ago.[12][13] Also the presence of dioctahedral smectite in the sediments indicates the presence of a very long dry season.[1] By studying the Ba/Ca ratio in tooth enamel samples of different taxa, it has been concluded that the equids of the genus Anchitherium ingested a higher proportion of herbaceous plants than the mastodons of the genus Gomphotherium and that the feeding habits of the suid Conohyus simorrensis were more omnivorous.[12] Among the fossil remains found, the abundance of the different taxa has been calculated from the bone remains identified between 1998 and 2006, with 47.47% of macrofaunal remains and 52.53% of microfaunal remains in the site.[1] Within the macrofauna, ruminants are represented with 14.4%, the genus Amchitherium with 12.7%, Gomphotherium angustidens with 11.1%, carnivores with 3% as well as Conohyus simorrensis and finally Prosantorhinus douvillei represents 2.6% of the taxa present. The most abundant taxon is the microvertebrate Megacricetodon collongensis (24%). As for other microvertebrates, there are Democricetodon larteti (11.2%), Democricetodon (0.1%), Cricetodon soriae (0.3%), Armantomys tricristatus (5%), Microdyromys koenigswaldi and M. monspeliensis (4.2%), Heteroxerus grivensis (4.8%), Prolagus oeningensis (0.1%), Lagopsis penai (1.5%), Galerix exilis (1.5%), Miosorex grivensis (0.6%) and non-mammals (0.7%).[1]

See also

Notes

- ↑ A biozone is a set of sedimentary rocks characterized by the presence of fossils of a certain taxon or taxa, which lived for a time shorter than the duration of a geologic stage. (Dercourt, J.; Pacquet, J. (1984). "El problema del tiempo en geología". Geología (in Spanish). p. 261. Reverte. p. 423. ISBN 9788429146127.)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hernández Fernández, M.; Cárdaba, J. A.; Cuevas-González, J.; Fesharaki, O.; Salesa, M. J.; Corrales, B.; Domingo, L.; Elez, J.; López Guerrero, P.; Sala-Burgos, N.; Morales, J.; López Martínez, N. (2006). "Los yacimientos de vertebrados del Mioceno medio de Somosaguas (Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid): implicaciones paleoambientales y paleoclimáticas". Estudios Geológicos (in Spanish). 62: 263–294. ISSN 0367-0449.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Mínguez Gandú, David (2000). "Marco estratigráfico y sedimentológico de los yacimientos paleontológicos miocenos de Somosaguas (Madrid, España)". Coloquios de paleontología (in Spanish). 51: 183–195. ISSN 1132-1660.

- 1 2 3 López Martínez, N.; Élez, J.; Hernando Hernando, J. M.; Cavia, A. Luis; Mazo, A.; Mímguez Gandú, David; Morales, J.; Polonio, I. Martín; Salesa, M. J.; Sánchez, I. M. (2000). "Los fósiles de Vertebrados de Somosaguas (Pozuelo, Madrid)". Coloquios de paleontología (in Spanish). 51: 71–85. ISSN 1132-1660.

- 1 2 3 "Los 'estudiantes' prehistóricos de Somosaguas". El Mundo (in Spanish). January 9, 2003. Archived from the original on June 15, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2013.

- 1 2 de la Fuente, Lucía (November 13, 2009). "Catorce millones de años después". madridiario.es (in Spanish). Retrieved January 6, 2011.

- ↑ Castilla, G.; Fesharaki, O.; Hernández Fernández, M.; Montesinos, R.; Cuevas, J.; López Martínez, N. (2006). "Experiencias educativas en el yacimiento paleontológico de Somosaguas (Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid". Enseñanza de las Ciencias de la Tierra (in Spanish). 14: 265–270. ISSN 1132-9157.

- ↑ IGME (1989): Geological map of Spain Scale 1:50,000. Madrid 559 (19-22). Centro de Publicaciones Ministerio de Industria y Energía. NIPO 232-86-010-2

- 1 2 3 Cádaba Barradas, J. A.; Cuevas-González, J.; Élez, J.; Fesharaki, O.; Hernández Fernández, M.; López Martínez, N.; Morales, J.; Sala-Burgos, N.; Salesa, M. J. (2006). "Revisión de la fauna de vertebrados fósiles de Somosaguas (Mioceno medio, Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid)". XXII Jornadas de paleontología (in Spanish): 94–96.

- ↑ Sala-Burgos, N.; Gil-Pita, R. (2006). "Detección de micromamíferos fósiles del yacimiento de Somosaguas Sur (Pozuelo de Alarcón, Madrid) mediante redes neuronales artificiales". XXII Jornadas de paleontología (in Spanish): 174–176.

- ↑ "Proyecto paleontológico de Somosaguas: Somosaguas Sur". Universidad Complutense de Madrid (in Spanish). Retrieved January 9, 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 Polonio Martín, I.; López Martínez, N. (2000). "Análisis tafonómico de los yacimientos de Somosaguas (Mioceno medio, Madrid)". Coloquios de paleontología (in Spanish). 51: 235–265. ISSN 1132-1660.

- 1 2 3 Domingo, L.; Cuevas-González, J.; Grimes, Stephen T.; López-Martínez, N. (2008). "Reconstrucción paleoclimática y paleoecológica del yacimiento de Somosaguas (Mioceno medio, Cuenca de Madrid) mediante el análisis geoquímico del esmalte dental de herbívoros (187-200)" (PDF). In Estevez, J.; Meléndez, G. (eds.). Palaeontologica Nova (in Spanish). SEPAZ. p. 196. ISBN 9788496214965.

- ↑ Zachos, James; Pagani, Mark; Sloan, Lisa; Thomas, Ellen; Billups, Katharina (2001). "Trends, Rhythms, and Aberrations in Global Climate 65 Ma to Present". Science. 292 (5517): 686–693. Bibcode:2001Sci...292..686Z. doi:10.1126/science.1059412. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 11326091. S2CID 2365991.