Sonia Gechtoff | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Sonia Alice Gechtoff September 25, 1926 |

| Died | February 1, 2018 (aged 91) New York City, U.S. |

| Education | San Francisco Art Institute |

| Alma mater | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts |

| Known for | Painting |

| Movement | Abstract Expressionism |

| Spouse | James Kelly (1953-2003; his death) |

| Children | 2 |

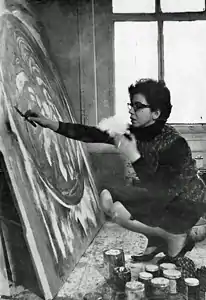

Sonia Gechtoff (September 25, 1926 – February 1, 2018)[1][2] was an American abstract expressionist painter.[3] Her primary medium was painting but she also created drawings and prints.

Early life and education

Sonia Gechtoff was born in Philadelphia to Ethel (Etya) and Leonid Gechtoff.[2] Her mother managed art galleries, including her own East and West gallery located at 3108 Fillmore Street in San Francisco.[4][5] Her father was a highly successful genre artist from Odesa, Ukraine.[6] He introduced his daughter to painting[7] and "had [her] sit beside him at his easel with a brush and paints and beginning at age six he was there to spur [her] on".[6]

Gechtoff's talent was recognized early and she was put in a succession of schools and classes for artistically gifted children. She graduated from the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts with a B.F.A. in 1950.[8][9]

Career

In 1951, Gechtoff relocated to San Francisco,[10] sharing her social and professional life with Bay Area artists such as Hassel Smith, Philip Roeber, Madeline Dimond, Ernest Briggs, Elmer Bischoff, Byron McClintock, and Deborah Remington. She was immersed in the heady culture of the San Francisco Bay Area Beat Generation.[11] According to Gechtoff, female abstract expressionists in San Francisco (such as Jay DeFeo, Joan Brown, Deborah Remington, and Lilly Fenichel) did not face the same discrimination as their New York counterparts.[12] After moving she studied lithography with James Budd Dixon at what is now called the San Francisco Art Institute.[9] She rapidly shifted to work as an Abstract Expressionist.[3] Some of her most well-known artwork was done in the Bay Area, including the lyrical Etya which is in the Oakland Museum of California.

Gechtoff married James "Jim" Kelly, another noted Bay Area artist, in 1953.

She gained national recognition in 1954, when her work was exhibited in the Guggenheim Museum's Younger American Painters show alongside Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, and Jackson Pollock.[12]

Shortly after her mother Ethel died in 1958, Gechtoff and Kelly moved to New York, where they immediately became a part of the New York art world.[4] She was represented by major New York galleries, among which were Poindexter and Gruenebaum, receiving consistently excellent reviews for her work. Teaching appointments and visiting professorships to New York University, Adelphi University, Art Institute of Chicago and the National Academy Museum and School, among others, were part of her professional life.[13]

Aesthetics

As a teenager, Gechtoff was heavily influenced by Ben Shahn's style of social realism[5], an international political and social movement that drew attention to the struggles of the working class and the poor.[12]

Gechtoff cited Clyfford Still's influence on her style (whom she met through her friend Ernie Briggs, but with whom she never studied).[6][13] She took important lessons about line and shape from Still's work, and is sometimes referred to as a "second-generation Abstract Expressionist".[14]

Her distinctive style emerged in the early 1950s: bright, bold works on "big" canvases.[15] Many of her works, like The Angel (1953–55), are abstracted self-portraits.[16] Gechtoff used vibrant colors and thick, energetic brushstroke to suggest a central figure whose arms stretch across the picture plane.[16] In 1956 she inaugurated her complex "hair" drawings, masses of line that tangled into wispy shapes that float on the paper. Her bold, swirling compositions won her a place in the United States Pavilion at the Brussels World's Fair in 1958.[17]

Later in her career, after moving to New York, Gechtoff began drawing inspiration from the Brooklyn Bridge, classical architecture, and the sea, whose forms are recognizable in her later series of collage-like paintings.[16] Gechtoff continued to develop her work throughout her career, never staying with one style. Always abstract, her work began to incorporate graphite after a switch to acrylics from oil. The result has given a sense of linear rhythm to her work. She also developed an interest in doing a series of work on a theme as well as sets, multiple canvases comprising a single complete work. One of her final set of works is the six canvas series "Skip's Garden".

According to Charles Dean, whose collection of Abstract Expressionist prints was acquired by the Library of Congress, Gechtoff was "the most prominent woman working in California in the '50s".[18]

In 1993 Gechtoff was elected to the National Academy of Design.[19] is the recipient of the 2013 Lee Krasner Lifetime Achievement Award,[20]

Gechtoff's work was included in the 1954 exhibition Younger American Painters at the Guggenheim,[21] the 1958 Brussels World Fair, USA Pavilion, "17 American Painters",[22] the 1977 Museum of Modern Art exhibition "Extraordinary Women',[23] and the 2016 exhibit "Women of Abstract Expressionism" at the Denver Art Museum,[24]

In 2023 her work was included in the exhibition Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970 at the Whitechapel Gallery in London.[25]

Public collections

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York[26]

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California[27]

- Museum of Modern Art, New York, New York[28]

- Whitney Museum, New York, New York[29]

- Menil Collection, Houston, Texas[30]

References

- ↑ Greenberger, Alex (2018-02-08). "Sonia Gechtoff, Abstract Expressionist Painter, Dies at 91". ARTnews. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- 1 2 "Sonia Gechtoff, Pioneering But Overlooked Artist of the Bay Area Ab-Ex Movement, Dies at 91". artnet News. 2018-02-08. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- 1 2 Kramer, Hilton (1982). "Art: Sonia Gechtoff at Her Best at Gruenebaum". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- 1 2 "The Art Scene Rebels of San Francisco". Literary Hub. September 2, 2016. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ↑ Landauer, Susan (1996). The San Francisco School of Abstract Expressionism. University of California Press. ISBN 0520086112.

- 1 2 3 Gechtoff, Sonia (2013-01-01). "Sonia Gechtoff: Art work". Columbia University. doi:10.7916/d8mg7mdx.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Acton, David, The Stamp of Impulse: Abstract Expressionist Prints, p. 110, The Worcester Art Museum, Worcester, MA, 2001. ISBN 90-5349-353-0

- ↑ Landauer 1996, p. 156.

- 1 2 "A Non-Objective Couple: Sonia Gechtoff & James Kelly". ArtfixDaily. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ↑ "The Cool Revival: Sonia Gechtoff in San Francisco - Art in America". Art in America. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ↑ "The Cool Revival: Sonia Gechtoff in San Francisco - Interviews - Art in America". www.artinamericamagazine.com. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 2016-06-29.

- 1 2 3 "The Divine Dozen: Sonia Gechtoff's Star Still Shines Brightly". 2016-06-22. Retrieved 2016-06-29.

- 1 2 Acton 2001, p. 110

- ↑ Landauer 1996, p. 152.

- ↑ Albright, Thomas, "Art in the San Francisco Bay Area: 1945-1950: An Illustrated History", University of California Press, 1985, p. 52. ISBN 978-0-520-05518-6

- 1 2 3 "Sonia Gechtoff". Artsy. Retrieved June 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Americans at Brussels: Soft Sell, Range & Controversy", Time Magazine, June 16, 1958, Vol. LXXI No. 24, p.73

- ↑ "Collector's Eye: Abstract Expressionist Prints", Forbes Collector, November 2005, Vol. 3, No. 11, p. 6.

- ↑ "Sonia Gechtoff". National Academy of Design. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ↑ "National Academy".

- ↑ Yau, John (27 July 2022). "Sonia Gechtoff Finally Gets Her Due". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ↑ Williams, Jared (1958-12-01). "Year in Review". Artist's Creed.

- ↑ "Sonia Gechtoff". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ↑ "Women of Abstract Expressionism | Denver Art Museum". Denver Art Museum. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ↑ "Action, Gesture, Paint". Whitechapel Gallery. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ↑ "River Porch III". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "Gechtoff, Sonia". SFMOMA. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "Sonia Gechtoff". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "Sonia Gechtoff". Whitney Museum of American Art. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ↑ "Sonia Gechtoff, American, 1926 - 2018 - Untitled". The Menil Collection. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

Further reading

- "Drawings by Extraordinary Women", The Museum of Modern Art, July 22, 1977, No. 55.

- "Sonia Gechtoff at Her Best at Gruenebaum", by Kramer, Hilton, The New York Times, January 8, 1982.

- Kramer, Hilton, "Reflections on Sonia Gechtoff", essay for Works on Paper, 1975–1987, a show at the Gruenebaum Gallery, 1987.

- "Sonia Gechtoff: Four Decades, 1956-1995: Works on Paper", Schick Art Gallery, Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, July 13-September 17, 1995.

- "Sonia Gechtoff: New Works January 5-February 13", Gruenebaum Gallery, Ltd, New York, 1982.

- "The Most Difficult Journey-The Poindexter Collection of American Modernist Painting", The University of Washington Press, 2002.

- "Can We Still Learn to Speak Martian?", by Yau, John, April 29, 2012, in Hyperallergic, an on-line forum/newsletter