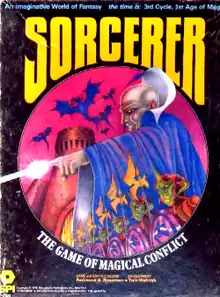

Sorcerer, subtitled "The Game of Magical Conflict", is a fantasy board wargame for 1–5 players published by Simulations Publications, Inc. (SPI) in 1975 that simulates magical combat.

Description

Sorcerer, a game for 1–5 players, is set in a place where seven different universes (represented by different colors) touch each other. Each player plays a sorcerer who controls one of the universes and tries to defeat the other sorcerers using magic. In addition to magical spells and human soldiers, each sorcerer can summon various magical creatures, teleport units from hex to hex, and fire energy bolts at opponents. The game offers a number of different scenarios for setup. There is a random attrition rule: during each turn, two colors are randomly chosen, and all units standing on those units are damaged or destroyed. In addition, sorcerers can summon a vortex, which moves randomly, damaging or destroying units it encounters while also creating new vortices.[1]

Components

The game box contains:[2]

- 22" x 34" paper hex grid map

- rule book

- 400 die-cut counters

- six-sided die

Victory conditions

Victory points are generated by capturing enemy forts, controlling the most cities, and by converting white spaces to the player's color. The player who collects the most victory points over a limited number of turns is the winner.[1]

Publication history

In Issue 44 of Strategy & Tactics (June 1974), a reader suggested that SPI develop a "fantasy/science fiction game on the tactical level depicting all sorts of weird things."[3] SPI designer Redmond A. Simonsen moved ahead with this project, and the result was Sorcerer. Simonsen also created the graphic design, while artwork was provided by Larry Catalano, Gwen England, Manfred F. Milkuhn, and Linda Mosca. The game was published by SPI in 1975.[4] As soon as it was released, Sorcerer rose to #1 on SPI's Top Ten Bestseller List, and stayed in the Top Ten for over a year.[5]

Reception

In the May 1976 edition of Airfix Magazine, Bruce Quarrie warned that the learning curve for the game was steep, saying, "While the rules are being learnt, Sorcerer will be a ponderous, slow-moving game, a sort of sorcerer's apprenticeship as the spells are being mastered. [...] As experience is gained and the instincts become surer, play should become faster, more fantastic and more furious." Quarrie's issue with the game was its tone, commenting "it might have been better if a form had been devised making it possible for the game to provide an amusing nonsense now and then without too much learning being called for. In its present form it is almost a serious business."[6]

Sorcerer was reviewed in The Space Gamer several times in 1976. In Issue #4 (Winter 1976), Glen Taylor recommended it, saying, "All in all, Sorcerer is a very good game. It presents an original fantasy situation in a fascinating and physically beautiful game format. The game is complex, but easy to learn. Scenarios are balanced, and the game employs the right proportion of skill and chance."[7] In Issue #5 (March–May 1976), Sumner N. Clarren also thought the game was worthwhile: "Because the game system of Sorcerer is such a departure from other fantasy or simulation games, it may take several sittings to fully master the intricacies of the rules. Once learned, however, the game moves quickly and the rules are remarkable clean and free of ambiguities. Even then, the best strategy and tactics for a talented sorcerer are not always obvious and must be learned with experience."[8] And in Issue #8 (October–November 1976), Linda Brzustowicz was a bit more nuanced, saying, "I found Sorcerer to be an enjoyable game. The one major point of the game I didn't like was the shallow development of the importance of magic."[2]

Rob Thompson reviewed Sorcerer for White Dwarf #1, giving the game an overall rating of 7 out of 10, and stated that "Sorcerer is an enjoyable game. A fun game without being a facile game. Colourful in looks and language. Sorcerer will be more attractive to gamers who are more interested in wargames as games rather than as historical simulations."[9]

In his 1977 book The Comprehensive Guide to Board Wargaming, Nicholas Palmer noted that some scenarios were not well-balanced, but overall felt that "The counters are splendidly varied in numerous colours, and the game is refreshingly different."[10]

In Issue 8 of Phoenix, Stephen and Andrew Gilham did not find the game lived up to pre-publication publicity, saying, "To be blunt, the game is boring." They disliked the map, calling it "a psychadaelic dayglo patchwork quilt." And they found the various uses of magic slow, weak, and useless. They concluded, "All in all, Sorcerer is pretty bad [...] Maybe someone knows how to play this game for fun and is not telling. From where we sit, it is a lemon."[11]

In the August 1978 edition of Dragon, although Jim Ward found the game could be enjoyable, he had issues with the combat resolution tables, which he thought were overly complicated. And he changed one rule: "[The game] was a lot of fun after we decided to ignore the random attrition rule." Ward recommended the game as long as players weren't expecting an overly complex game, saying, "Fantasy buffs will enjoy playing the game from the creation of creatures and tossing of energy bolts standpoint. On the other hand, one shouldn't expect any complicated tactical situations to occur."[1]

In the inaugural Issue of Ares, Eric Goldberg gave the game a below-average score of 5 out of 9, saying, "The game system is nice, but it seems more appropriate for an abstract color war game than for a fantasy game. In the final analysis, Sorcerer fails as both a game and as fantasy."[12]

In the 1980 book The Complete Book of Wargames, game designer Jon Freeman was ambivalent, saying, “This is a strange combination of the different and the ordinary. On the one hand, the basic premise — colored hexes, conjured units, teleportation — are different enough to be confusing. On the other hand, magical units all fight by conventional rules and resolve combat on a conventional [Combat Results Table]. Sorcerers fling magic bolts as if they were artillery. Sorcerers must expend movement points to accomplish tasks — a procedure similar to that of StarSoldier or even Sniper!" Freeman gave this game an Overall Evaluation of "Fair to Good", concluding, "Once the system is grasped, the presence of optimum strategies makes play stereotyped."[13]

Awards

At the 1978 Origins Awards, Sorcerer was a finalist for the Charles S. Roberts Award for "Best Fantasy Board Game of 1977."

Other reviews and commentary

- Moves #25 (Feb/Mar 1976)

References

- 1 2 3 Ward, Jim (August 1979). "The Dragon's Augury". Dragon. TSR, Inc. (28): 48.

- 1 2 Brzustowicz, Linda (October–November 1976). "Reviews". The Space Gamer. No. 8. pp. 18–19.

- ↑ "Reader Feedback". Strategy & Tactics. No. 44. Simulations Publications Inc. June 1974.

- ↑ "Sorcerer: The Game of Magical Conflict (1975)". boardgamegeek.com. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ↑ "SPI Best Selling Games – 1975". spigames.net. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ↑ Quarrie, Bruce (May 1976). "News for the Wargamer". Airfix Magazine. Vol. 17, no. 9. p. 540.

- ↑ Taylor, Glen (1976). "Reviews". The Space Gamer. No. 4. pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Clarren, Sumner N. (March–May 1976). "Sorcerer and White Bear and Red Moon". The Space Gamer. Metagaming (5): 25–26.

- ↑ Thompson, Rob (June–July 1977). "Open Box". White Dwarf. No. 1. pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Palmer, Nicholas (1977). The Comprehensive Guide to Board Wargaming. London: Sphere Books. pp. 174–175.

- ↑ Gilham, Stephen and Andrew (July–August 1977). "Sorcerer: A Critique". Phoenix. No. 8. pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Goldberg, Eric (March 1980). "A Galaxy of Games". Ares Magazine. No. 1. p. 34.

- ↑ Freeman, Jon (1980). The Complete Book of Wargames. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 238–239.