| South White Carniolan dialect | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Slovenia |

| Region | Southern part of White Carniola, southern from Dobliče and Griblje. |

| Ethnicity | Slovenes |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Southeastern Slovene dialect

|

| Dialects |

|

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

South White Carniolan dialect | |

| South Slavic languages and dialects |

|---|

This article uses Logar transcription.

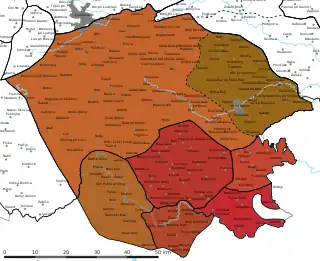

The South White Carniolan dialect (Slovene: južnobelokranjsko narečje [juʒnɔbɛlɔˈkɾàːnskɔ naˈɾéːt͡ʃjɛ],[1] južna belokranjščina,[2] Serbo-Croatian: južnobelokrajinsko narječje) is a Slovene dialect heavily influenced by Shtokavian dialects.[3] It is spoken in southern White Carniola, south of Dobliče and Griblje.[3] However, it is not spoken in all the settlements in that area because some are almost completely inhabited by immigrants, and so Shtokavian heavily influenced by Slovene is instead spoken there.[4][5] The dialect borders the North White Carniolan dialect to the north, the Prigorje dialect to the east, Central Chakavian to southeast, the Eastern Goran dialect to the south, the Kostel dialect to the southwest, and the mixed Kočevje subdialects to the northwest, as well as those mixed Shtokavian dialects.[6][7] The dialect belongs to the Lower Carniolan dialect group, and it evolved from the Lower Carniolan dialect base.[8][9]

Geographical distribution

The border between the South and North White Carniolan dialects is rather clear; it was already defined by Tine Logar. It follows the line from Jelševnik to Krasinec, but it runs a bit south of Črnomelj.[10] The border with the mixed Kočevje subdialects is a bit more questionable because both dialects are poorly researched and an accurate border cannot be drawn. The border with the Kostel dialect is also probably wrong because the Kostel dialect extends along the Kolpa River in Croatia, but (as marked on the map) not on Slovene side, and so the Kostel dialect might actually be spoken there.[11] The border with the Shtokavian dialects is even more blurred. The villages of Bojanci, Marindol, Miliči, and Paunoviči are mainly inhabited by Serbs, and so Shtokavian is spoken there,[5] whereas speakers in neighboring villages such as Preloka and Adlešiči were already thought to speak a Slovene dialect by Tine Logar.[3] He also noted that an ikavian dialect is spoken in Tribuče.[12]

According to what is known today, the dialect ranges from Adlešiči and Preloka north to Krasinec, west to the Kočevje Rog Plateau and along the Kolpa River at least to Stari Trg ob Kolpi, apart from the aforementioned Serbian villages. To the south and east, it is currently thought that the Slovenia–Croatia border is also the dialect border.

History

White Carniola was inhabited by Slovenes after the 13th century, and even then it was rather remote from other Slovenes on the Kočevje Rog Plateau to the west and in the Gorjanci Hills to the north. The immigration of the Gottschee Germans left the Slovenes even more closely connected to Croatia. However, they, still maintained contact with other Slovenes that lived on the other side of the Gorjanci Hills to the north. Differentiation between the North and South White Carniolan dialects occurred in the 15th and 16th centuries, when the Ottomans started attacking Bosnia and Dalmatia. Because of that, White Carniolans started moving north of the Gorjanci Hills, while the mostly cleared region of southern White Carniola, especially along Kolpa River, was newly inhabited by immigrants from Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia. The White Carniolan dialect then formed from a mix of the old White Carniolan dialect, Serbo-Croatian dialects, and dialects from newly settled Slovenes after the Ottoman invasions. Serbo-Croatian influence was the most prominent in the south, whereas in the north it had negligible influence. Therefore, today the White Carniolan dialect is split based on how much influence it received from Serbo-Croatian.[10]

Accentual changes

The South White Carniolan microdialects west of Vinica and Dragatuš retained pitch accent on long syllables, which was lost in the eastern microdialects. The long neoacute on the final syllables became a circumflex (*kĺúːč → *kĺùːč). Long and short syllables are still differentiated. It also underwent the same six accentual changes as the North White Carniolan dialect: *ženȁ → *žèna, *məglȁ → *mə̀gla, *sěnȏ / *prosȏ → *sě̀no / *pròso, *visȍk → vìsok, and *kováč → *kòvač, but the southern microdialects have also partially undergone the accent shift *kolȅno → *ˈkoleno. The northern microdialects (Dragatuš, Dobliče) have not undergone the *kováč → *kòvač shift, and the western microdialects have not fully undergone the *sěnȏ / *prosȏ → *sě̀no / *pròso accent shift.[13]

Phonology

The phonological characteristics of the dialect are not characteristic for Slovene dialects, and some changes occurred that are known for Serbo-Croatian, but not for Slovene. The dialect is one of the most diverse and understudied dialects, mainly because of Serbo-Croatian influence.[14]

Alpine Slovene *ě̑ has evolved into ḙː in the north, ẹː in Vinica and Preloka (in the southern part), iːe/ieː in Stari Trg (in the west), and ẹːi̯ elsewhere. The evolution is confusing because in Zilje, a village between Vinica and Preloka, the pronunciation is ẹːi̯, not ẹː, and in Predgrad, which is even further west than Stari Trg, the pronunciation is also ẹːi̯. The vowel *ę̑ mostly evolved into ẹː. In the east, it evolved into ẹːi̯ and into iːe/ieː in the west.

The vowel *ȏ evolved into uː in the north and west, ọː in the south, and ọːu̯ in the east. Nasal *ǫ̑ evolved into ọː in the northernmost microdialects and in the south, and into uː in the middle (Dragatuš) and east. It evolved into ọːu̯ in Zilje and Bedenj.

The vowel *ȗ mostly remained uː. In Dobliče and Dragatuš, üː is also present, and in the west it evolved into iː. Alpine Slavic *ł̥̄ evolved into uː.

Long old acute vowels and the short neoacute (those after accent shifts) became short; this is a feature of Serbo-Croatian dialects, and so this was probably influenced by the immigrants:

- *ę́, *ę̀, *è and *ě́ evolved into e.

- *ǫ́ and non-final *ò evolved into o.

- *ú evolved into ö in Tanča Gora and Zapudje, and into ẹ in the west.

- *á and *í evolved into a and i, respectively.

- After the *ženȁ > *žèna shift, e and o turned into:

- äː and ọː, respectively, in the west,

- ẹː and ọː, respectively, in the north and east, and

- e and o, respectively, in the south.

- After the *məglȁ > *mə̀gla shift, ə turned into:

- ə in the south and east,

- əː in the north, and

- aː in the west.

Alpine Slovene *l turned into ł, *u̯m- turned into xm- in the northern, eastern, and southern microdialects, and into ɣm- in the western microdialects. If a word started with u, v appeared before it. In the western dialects, g turned into ɣ. Palatal ć, šć, ń, and ĺ remain palatal, except in the northern and eastern dialects, where they become only palatalized. Another feature is that only the northern microdialects devoice non-sonorants before the end of a word; elsewhere they remain voiced. In Zapudje, final -g devoices into -x.[15]

Morphology

The instrumental plural was replaced by locative plural forms in the eastern dialects.[16]

References

- ↑ Smole, Vera. 1998. "Slovenska narečja." Enciklopedija Slovenije vol. 12, pp. 1–5. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, p. 2.

- ↑ Logar (1996:203)

- 1 2 3 Logar (1996:82)

- ↑ Šekli (2018:374)

- 1 2 Petrović, Tanja (2006). Ne tu, ne tam : Srbi v Beli krajini in njihova jezikovna ideologija v procesu zamenjave jezika [Not Here, Not There: Serbs in White Carniola and Their Ideology in the Process of Switching the Language.] (in Slovenian). Translated by Đukanović, Maja. Ljubljana: Založba ZRC. pp. 30–35. doi:10.3986/9616568531. ISBN 961-6568-53-1.

- ↑ "Karta slovenskih narečij z večjimi naselji" (PDF). Fran.si. Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša ZRC SAZU. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ↑ Kapović, Mate (2015). POVIJEST HRVATSKE AKCENTUACIJE (in Croatian). Zagreb: Zaklada HAZU. pp. 40–46. ISBN 978-953-150-971-8.

- ↑ Logar, Tine; Rigler, Jakob (2016). Karta slovenskih narečij (PDF) (in Slovenian). Založba ZRC.

- ↑ Šekli (2018:335–339)

- 1 2 Logar (1996:79)

- ↑ Gostenčnik, Januška (2020). Kostelsko narečje (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. p. 355.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Logar (1996:85)

- ↑ Logar (1996:84–85)

- ↑ Logar (1996:82–84)

- ↑ Logar (1996:85)

- ↑ Logar (1996:81)

Bibliography

- Logar, Tine (1996). Kenda-Jež, Karmen (ed.). Dialektološke in jezikovnozgodovinske razprave [Dialectological and etymological discussions] (in Slovenian). Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU, Inštitut za slovenski jezik Frana Ramovša. ISBN 961-6182-18-8.

- Šekli, Matej (2018). Legan Ravnikar, Andreja (ed.). Topologija lingvogenez slovanskih jezikov (in Slovenian). Translated by Plotnikova, Anastasija. Ljubljana: Znanstvenoraziskovalni center SAZU. ISBN 978-961-05-0137-4.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)