| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

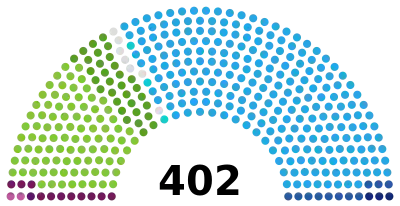

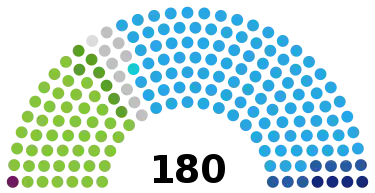

All 402 seats in the Congress of Deputies and 180 (of 360) seats in the Senate 202 seats needed for a majority in the Congress of Deputies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The 1899 Spanish general election was held on Sunday, 16 April (for the Congress of Deputies) and on Sunday, 30 April 1899 (for the Senate), to elect the 9th Cortes of the Kingdom of Spain in the Restoration period. All 401 seats in the Congress of Deputies (plus one special district) were up for election, as well as 180 of 360 seats in the Senate.

It was the first election to be held after the Spanish–American War, which had seen the loss of the Spanish colonies in the Caribbean and Pacific with the Treaty of Paris signed on 10 December 1898. Together with Spain's defeat in the war, internal rivalries within the Liberal Party led to a major split—led by Germán Gamazo and his "gamacist" faction—and the downfall of Práxedes Mateo Sagasta's government, with Francisco Silvela being appointed as new prime minister in March 1899.

In the ensuing general election, Silvela's Conservative party secured an overall majority in both chambers.

Overview

Electoral system

The Spanish Cortes were envisaged as "co-legislative bodies", based on a nearly perfect bicameral system. Both the Congress of Deputies and the Senate had legislative, control and budgetary functions, sharing equal powers except for laws on contributions or public credit, where the Congress had preeminence.[1][2] Voting for the Cortes was on the basis of universal manhood suffrage, which comprised all national males over 25 years of age, having at least a two-year residency in a municipality and in full enjoyment of their civil rights.[3][4]

For the Congress of Deputies, 91 seats were elected using a partial block voting system in 26 multi-member constituencies, with the remaining 310 being elected under a one-round first-past-the-post system in single-member districts. Candidates winning a plurality in each constituency were elected. In constituencies electing eight seats or more, electors could vote for no more than three candidates less than the number of seats to be allocated; in those with more than four seats and up to eight, for no more than two less; in those with more than one seat and up to four, for no more than one less; and for one candidate in single-member districts. The Congress was entitled to one member per each 50,000 inhabitants, with each multi-member constituency being allocated a fixed number of seats. Additionally, literary universities, economic societies of Friends of the Country and officially organized chambers of commerce, industry and agriculture were entitled to one seat per each 5,000 registered voters that they comprised, which resulted in one additional special district for the 1899 election. The law also provided for by-elections to fill seats vacated throughout the legislature.[1][5][6][7]

As a result of the aforementioned allocation, each Congress multi-member constituency was entitled the following seats:[6][8][9][10][11][12]

| Seats | Constituencies |

|---|---|

| 8 | Madrid |

| 7 | Barcelona(+2) |

| 5 | Palma, Seville(+1) |

| 3 | Alicante, Almería, Badajoz, Burgos, Cádiz, Cartagena, Córdoba, Granada, Jaén, Jerez de la Frontera, La Coruña, Lugo, Málaga, Murcia, Oviedo, Pamplona, Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Santander, Tarragona, Valencia, Valladolid, Zaragoza |

For the Senate, 180 seats were indirectly elected by the local councils and major taxpayers, with electors voting for delegates instead of senators. Elected delegates—equivalent in number to one-sixth of the councillors in each local council—would then vote for senators using a write-in, two-round majority voting system. Following a redistribution of the 19 senators allocated to Cuba and Puerto Rico as a result of the loss by Spain of these colonies, the provinces of Barcelona, Madrid and Valencia were allocated four seats each, whereas each of the remaining provinces was allocated three seats, for a total of 150. The remaining 30 were allocated to special districts comprising a number of institutions, electing one seat each—the archdioceses of Burgos, Granada, Santiago de Compostela, Seville, Tarragona, Toledo, Valencia, Valladolid and Zaragoza; the Royal Spanish Academy; the royal academies of History, Fine Arts of San Fernando, Exact and Natural Sciences, Moral and Political Sciences and Medicine; the universities of Madrid, Barcelona, Granada, Oviedo, Salamanca, Santiago, Seville, Valencia, Valladolid and Zaragoza; and the economic societies of Friends of the Country from Madrid, Barcelona, León, Seville and Valencia. An additional 180 seats comprised senators in their own right—the Monarch's offspring and the heir apparent once coming of age; Grandees of Spain of the first class; Captain Generals of the Army and the Navy Admiral; the Patriarch of the Indies and archbishops; and the presidents of the Council of State, the Supreme Court, the Court of Auditors, the Supreme War Council and the Supreme Council of the Navy, after two years of service—as well as senators for life (who were appointed by the Monarch).[1][13][14]

Election date

The term of each chamber of the Cortes—the Congress and one-half of the elective part of the Senate—expired five years from the date of their previous election, unless they were dissolved earlier. The previous Congress and Senate elections were held on 27 March and 10 April 1898, which meant that the legislature's terms would have expired on 27 March and 10 April 1903, respectively. The monarch had the prerogative to dissolve both chambers at any given time—either jointly or separately—and call a snap election.[1][6][13] There was no constitutional requirement for simultaneous elections for the Congress and the Senate, nor for the elective part of the Senate to be renewed in its entirety except in the case that a full dissolution was agreed by the monarch. Still, there was only one case of a separate election (for the Senate in 1877) and no half-Senate elections taking place under the 1876 Constitution.

The Cortes were officially dissolved on 16 March 1899, with the dissolution decree setting the election dates for 16 April (for the Congress) and 30 April 1899 (for the Senate) and scheduling for both chambers to reconvene on 2 June.[15]

Background

The Spanish Constitution of 1876 enshrined Spain as a constitutional monarchy, awarding the monarch power to name senators and to revoke laws, as well as the title of commander-in-chief of the army. The monarch would also play a key role in the system of el turno pacífico (English: the Peaceful Turn) by appointing and dismissing governments and allowing the opposition to take power. Under this system, the major political parties of the time, the conservatives and the liberals—characterized as elite parties with loose structures and dominated by internal factions led by powerful individuals—alternated in power by means of election rigging, which they achieved through the encasillado, using the links between the Ministry of Governance, the provincial civil governors and the local bosses (caciques) to ensure victory and exclude minor parties from the power sharing.[16][17]

Upon assuming office in October 1897, Prime Minister Práxedes Mateo Sagasta recalled Valeriano Weyler as governor of Cuba and appointed pro-autonomy Segismundo Moret as minister of Overseas, in an attempt to tackle the deteriorating situation in the Cuban War of Independence, with two autonomy charters—for Cuba and Puerto Rico—being approved shortly afterwards.[18] The involvement of the United States, especially following the sinking of the USS Maine and the breakout of the Spanish–American War in April 1898, led to a 10-week campaign in which the Sagasta government sued for peace after the loss of two Spanish naval squadrons in the battles of Santiago de Cuba and Manila Bay.[19] The war resulted in Spain losing its American and Asia-Pacific colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Philippines and Guam under the terms of the 1898 Treaty of Paris, with the remaining Spanish possessions in the Pacific being sold to the German Empire.[20]

Sagasta resigned in March 1899 over his government's perceived responsibility in these losses, with Queen Regent Maria Christina handing power to Francisco Silvela. Germán Gamazo, several times-minister under Liberal cabinets, had split from the party in October 1898 following the Ribot scandal—a controversy involving Cádiz governor and Gamazo's ally Pascual Ribot—which he attributed to an internal conspiration within the Liberal Party to get rid of him as Development minister.[21][22][23][24]

Results

Congress of Deputies

| ||||

| Parties and alliances | Popular vote | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | |||

| Conservative Union–Liberal Conservative Party (UC–PLC) | 240 | |||

| Liberal Party (PL) | 92 | |||

| Gamacist Liberals (G) | 32 | |||

| Republican Fusion (FR) | 11 | |||

| Tetuanist Conservatives (T) | 11 | |||

| Liberal Reformist Party (PLR) | 3 | |||

| Carlist Coalition (CC) | 3 | |||

| Federal Republican Party (PRF) | 2 | |||

| Blasquist Republicans (RB) | 1 | |||

| Independents (INDEP) | 7 | |||

| Total | 402 | |||

| Votes cast / turnout | ||||

| Abstentions | ||||

| Registered voters | ||||

| Sources[25][26][27][28][29][30][31] | ||||

Senate

| ||

| Parties and alliances | Seats | |

|---|---|---|

| Conservative Union–Liberal Conservative Party (UC–PLC) | 103 | |

| Liberal Party (PL) | 47 | |

| Gamacist Liberals (G) | 7 | |

| Tetuanist Conservatives (T) | 7 | |

| Carlist Coalition (CC) | 4 | |

| Republican Fusion (FR) | 1 | |

| Liberal Reformist Party (PLR) | 1 | |

| Independents (INDEP) | 1 | |

| Archbishops (ARCH) | 9 | |

| Total elective seats | 180 | |

| Sources[32][33][34][35][36][37][38] | ||

Distribution by group

| Group | Parties and alliances | C | S | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UC–PLC | Conservative Union–Liberal Conservative Party (UC–PLC) | 239 | 100 | 343 | ||

| Basque Dynastics (Urquijist) (DV) | 1 | 3 | ||||

| PL | Liberal Party (PL) | 92 | 47 | 139 | ||

| G | Gamacist Liberals (G) | 32 | 7 | 39 | ||

| T | Tetuanist Conservatives (T) | 11 | 7 | 18 | ||

| FR | National Republican Party (PRN) | 10 | 1 | 12 | ||

| Centralist Republican Party (PRC) | 1 | 0 | ||||

| CC | Traditionalist Communion (Carlist) (CT) | 3 | 3 | 7 | ||

| Integrist Party (PI) | 0 | 1 | ||||

| PLR | Liberal Reformist Party (PLR) | 3 | 1 | 4 | ||

| PRF | Federal Republican Party (PRF) | 2 | 0 | 2 | ||

| RB | Blasquist Republicans (RB) | 1 | 0 | 1 | ||

| INDEP | Independents (INDEP) | 4 | 1 | 8 | ||

| Independent Catholics (CAT) | 2 | 0 | ||||

| Independent Possibilists (P.IND) | 1 | 0 | ||||

| ARCH | Archbishops (ARCH) | 0 | 9 | 9 | ||

| Total | 402 | 180 | 582 | |||

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Constitución de la Monarquía Española". Constitution of 30 June 1876 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ↑ "El Senado en la historia constitucional española". Senate of Spain (in Spanish). Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ↑ García Muñoz 2002, pp. 106–107.

- ↑ Carreras de Odriozola & Tafunell Sambola 2005, p. 1077.

- ↑ "Ley electoral de los Diputados a Cortes". Law of 28 December 1878 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Ley electoral para Diputados a Cortes". Law of 26 June 1890 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ↑ "Ley mandando que los distritos para las elecciones de Diputados á Córtes sean los que se expresan en la división adjunta". Law of 1 January 1871 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ↑ "Ley dividiendo la provincia de Guipúzcoa en distritos para la elección de Diputados a Cortes". Law of 23 June 1885 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ "Ley dividiendo el distrito electoral de Tarrasa en dos, que se denominarán de Tarrasa y de Sabadell". Law of 18 January 1887 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ "Ley fijando la división de la provincia de Alava en distritos electorales para Diputados á Cortes". Law of 10 July 1888 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ "Leyes aprobando la división electoral de las provincias de León y Vizcaya". Law of 2 August 1895 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ↑ "Leyes aprobando la división electoral en las provincias de Sevilla y de Barcelona". Law of 5 July 1898 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 September 2022.

- 1 2 "Ley electoral de Senadores". Law of 8 February 1877 (PDF) (in Spanish). Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ↑ "Real decreto disponiendo el número de Senadores que han de elegir las provincias que se citan" (PDF). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (76): 1021. 16 March 1899.

- ↑ "Real decreto declarando disueltos el Congreso de los Diputados y la parte electiva del Senado, y convocando á nuevas elecciones en las fechas que se expresan" (PDF). Gaceta de Madrid (in Spanish). Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado (76): 1021. 16 March 1899.

- ↑ Martorell Linares 1997, pp. 139–143.

- ↑ Martínez Relanzón 2017, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ AEBOE 2023, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ AEBOE 2023, pp. 12–14.

- ↑ "Práxedes Mateo-Sagasta Escolar" (in Spanish). Royal Academy of History. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ↑ Hidalgo Marín 1995, p. 109.

- ↑ "Germán Gamazo Calvo" (in Spanish). Royal Academy of History. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ↑ Cañas Carrillo, Jesús Antonio (24 February 2017). "El origen de la leyenda en El País". Diario de Cádiz (in Spanish). Cádiz. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ↑ "Mes de octubre. Día 31. La carta de los gamacistas". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Año Político. 1 January 1899. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- ↑ Armengol i Segú & Varela Ortega 2001, pp. 655–776.

- ↑ "Las elecciones de hoy". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Correspondencia de España. 16 April 1899. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ↑ "La jornada electoral". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Heraldo de Madrid. 17 April 1899. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ↑ "Las elecciones". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Reforma. 17 April 1899. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ↑ "Las elecciones". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El País. 18 April 1899. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ "Notas políticas". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Izquierda Dinástica. 19 April 1899. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ "Mes de abril. Día 16. Elecciones de diputados a Cortes". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Año Político. 1 January 1900. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ↑ "Datos oficiales". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Época. 30 April 1899. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Datos oficiales". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Imparcial. 1 May 1899. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ "Resumen general". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Correspondencia Militar. 1 May 1899. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ "Las elecciones de senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Liberal. 1 May 1899. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ "Estadística". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Liberal. 1 May 1899. Retrieved 17 April 2022.

- ↑ "Elecciones de senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). La Reforma. 1 May 1899. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

- ↑ "Mes de abril. Día 30. Elección de senadores". National Library of Spain (in Spanish). El Año Político. 1 January 1900. Retrieved 24 September 2022.

Bibliography

- Fernández Almagro, Melchor (1943). "Las Cortes del siglo XIX y la práctica electoral". Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish) (9–10): 383–419. ISSN 0048-7694. Retrieved 16 December 2020.

- Hidalgo Marín, Inés Sofía (1995). University of Valladolid (ed.). "La familia Gamazo: elite castellana en la restauración (1874-1923)". Investigaciones históricas: Época moderna y contemporánea (in Spanish) (15): 107–118. ISSN 0210-9425. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

- Martorell Linares, Miguel Ángel (1997). "La crisis parlamentaria de 1913-1917. La quiebra del sistema de relaciones parlamentarias de la Restauración". Revista de Estudios Políticos (in Spanish). Madrid: Centro de Estudios Constitucionales (96): 137–161.

- Martínez Ruiz, Enrique; Maqueda Abreu, Consuelo; De Diego, Emilio (1999). Atlas histórico de España (in Spanish). Vol. 2. Bilbao: Ediciones KAL. pp. 109–120. ISBN 9788470903502.

- Armengol i Segú, Josep; Varela Ortega, José (2001). El poder de la influencia: geografía del caciquismo en España (1875-1923) (in Spanish). Madrid: Marcial Pons Historia. pp. 655–776. ISBN 9788425911521.

- García Muñoz, Montserrat (2002). "La documentación electoral y el fichero histórico de diputados". Revista General de Información y Documentación (in Spanish). 12 (1): 93–137. ISSN 1132-1873. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Carreras de Odriozola, Albert; Tafunell Sambola, Xavier (2005) [1989]. Estadísticas históricas de España, siglos XIX-XX (PDF) (in Spanish). Vol. 1 (II ed.). Bilbao: Fundación BBVA. pp. 1072–1097. ISBN 84-96515-00-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015.

- Martínez Relanzón, Alejandro (2017). "Political Modernization in Spain Between 1876 and 1923". Annales Universitatis Mariae Curie-Sklodowska, sectio K. Madrid: Maria Curie-Skłodowska University. 24 (1): 145–154. doi:10.17951/k.2017.24.1.145. S2CID 159328027.

- AEBOE (2023). State Agency for the Official State Gazette (ed.). "El desastre de 1898 visto por las figuras políticas de la Restauración: 125 años de la guerra de Cuba (1898-2023)". Official State Gazette (in Spanish). Madrid. ISBN 9788434029002. Retrieved 3 May 2023.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)