Special wards of Tokyo

東京特別区 | |

|---|---|

Shinjuku, one of Tokyo's special wards | |

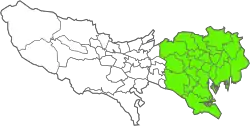

Located in the green highlights | |

| |

| Country | Japan |

| Island | Honshu |

| Region | Kantō |

| Prefecture | Tokyo |

| Area | |

| • Special wards | 618.8 km2 (238.9 sq mi) |

| Population (October 1, 2020) | |

| • Special wards | 9,733,276 |

| • Density | 15,729.27/km2 (40,738.6/sq mi) |

| Administrative divisions of Japan |

|---|

| Prefectural |

| Prefectures |

| Sub-prefectural |

| Municipal |

| Sub-municipal |

Special wards (特別区, tokubetsu-ku) are a special form of municipalities in Japan under the 1947 Local Autonomy Law. They are city-level wards: primary subdivisions of a prefecture with municipal autonomy largely comparable to other forms of municipalities.

Although the autonomy law today allows for special wards to be established in other prefectures, to date, they only exist in Tokyo which consists of 23 special wards and 39 other, ordinary municipalities (cities, towns, and villages).[1] The special wards of Tokyo occupy the land that was Tokyo City in its 1936 borders before it was abolished under the Tōjō Cabinet in 1943 to become directly ruled by the prefectural government, then renamed to "Metropolitan". During the Occupation of Japan, municipal autonomy was restored to former Tokyo City by the establishment of special wards, each with directly elected mayor and assembly, as in any other city, town or village in Tokyo and the rest of the country.

In Japanese, they are collectively also known as "Wards area of Tokyo Metropolis" (東京都区部, Tōkyō-to kubu), "former Tokyo City" (旧東京市, kyū-Tōkyō-shi), or less formally the 23 wards (23区, nijūsan-ku) or just Tokyo (東京, Tōkyō) if the context makes obvious that this does not refer to the whole prefecture. Today, all wards refer to themselves as a city in English, but the Japanese designation of special ward (tokubetsu-ku) remains unchanged. They are a group of 23 municipalities; there is no associated single government body separate from the Tokyo Metropolitan Government which governs all 62 municipalities of Tokyo, not only the special wards.

Analogues in other countries

Analogues exist in historic and contemporary Chinese and Korean administration: "Special wards" are city-independent wards, analogously, "special cities/special cities" (teukbyeol-si/tokubetsu-shi) are province-/prefecture-independent cities and were intended to be introduced under SCAP in Japan, too; but in Japan, implementation was stalled, and in 1956 special cities were replaced in the Local Autonomy Law with designated major cities which gain additional autonomy, but remain part of prefectures. In everyday English, Tokyo as a whole is also referred to as a city even though it contains 62 cities, towns, villages and special wards. The closest English equivalents for the special wards would be the London boroughs or New York City boroughs if Greater London and New York City had been abolished in the same way as Tokyo City, making the boroughs top-level divisions of England or New York state.

Differences from other municipalities

Although special wards are autonomous from the Tokyo metropolitan government, they also function as a single urban entity in respect to certain public services, including water supply, sewage disposal, and fire services. These services are handled by the Tokyo metropolitan government, whereas cities would normally provide these services themselves. This situation is identical between the Federal District and its 33 administrative regions in Brazil. To finance the joint public services it provides to the 23 wards, the metropolitan government levies some of the taxes that would normally be levied by city governments, and also makes transfer payments to wards that cannot finance their own local administration.[2]

Waste disposal is handled by each ward under direction of the metropolitan government. For example, plastics were generally handled as non-burnable waste until the metropolitan government announced a plan to halt burying of plastic waste by 2010; as a result, about half of the special wards now treat plastics as burnable waste, while the other half mandate recycling of either all or some plastics.[3]

Unlike other municipalities (including the municipalities of western Tokyo), special wards were initially not considered to be local public entities for purposes of the Constitution of Japan. This means that they had no constitutional right to pass their own legislation, or to hold direct elections for mayors and councilors. While these authorities were granted by statute during the US-led occupation and again in 1975, they could be unilaterally revoked by the National Diet; similar measures against other municipalities would require a constitutional amendment. The denial of elected mayors to the special wards was reaffirmed by the Supreme Court in the 1963 decision Japan v. Kobayashi et al. (also known as Tokyo Ward Autonomy Case).

In 1998, the National Diet passed a revision of the Local Autonomy Law (effective in the year 2000) that implemented the conclusions of the Final Report on the Tokyo Ward System Reform increasing their fiscal autonomy and established the wards as basic local public entities.

History

The word "special" distinguishes them from the wards (区, ku) of other major Japanese cities. Before 1943, the wards of Tokyo City were no different from the wards of Osaka or Kyoto. These original wards numbered 15 in 1889. Large areas from five surrounding districts were merged into the city in 1932 and organized in 20 new wards, bringing the total to 35; the expanded city was also referred to as "Greater Tokyo" (大東京, Dai-Tōkyō). By this merger, together with smaller ones in 1920 and 1936, Tokyo City came to expand to the current city area.

1943–1947

On March 15, 1943, as part of wartime totalitarian tightening of controls, Tokyo's local autonomy (elected council and mayor) under the Imperial municipal code was eliminated by the Tōjō cabinet and the Tokyo city government and (Home ministry appointed) prefectural government merged into a single (appointed) prefectural government;[4] the wards were placed under the direct control of the prefecture.

1947–2000

The 35 wards of the former city were integrated into 22 on March 15, 1947 just before the legal definition of special wards was given by the Local Autonomy Law, enforced on May 3 the same year. The 23rd ward, Nerima, was formed on August 1, 1947 when Itabashi was split again. The postwar reorganization under the US-led occupation authorities democratized the prefectural administrations but did not include the reinstitution of Tokyo City. Seiichirō Yasui, a former Home Ministry bureaucrat and appointed governor, won the first Tokyo gubernatorial election against Daikichirō Tagawa, a former Christian Socialist member of the Imperial Diet, former vice mayor of Tokyo city and advocate of Tokyo city's local autonomy.

Since the 1970s, the special wards of Tokyo have exercised a considerably higher degree of autonomy than the administrative wards of cities (that unlike Tokyo City retained their elected mayors and assemblies) but still less than other municipalities in Tokyo or the rest of the country, making them less independent than cities, towns or villages, but more independent than city subdivisions. Today, each special ward has its own elected mayor (区長, kuchō) and assembly (区議会, kugikai).

2000–present

In 2000, the National Diet designated the special wards as local public entities (地方公共団体, chihō kōkyō dantai), giving them a legal status similar to cities.

The wards vary greatly in area (from 10 to 60 km2) and population (from less than 40,000 to 830,000), and some are expanding as artificial islands are built. Setagaya has the most people, while neighboring Ōta has the largest area.

The total population census of the 23 special wards had fallen under 8 million as the postwar economic boom moved people out to suburbs, and then rose as Japan's lengthy stagnation took its toll and property values drastically changed, making residential inner areas up to 10 times less costly than during peak values. Its population was 8,949,447 as of October 1, 2010,[5] about two-thirds of the population of Tokyo and a quarter of the population of the Greater Tokyo Area. As of December 2012, the population passed 9 million; the 23 wards have a population density of 14,485 per square kilometre (37,501 per square mile).

The Mori Memorial Foundation put forth a proposal in 1999 to consolidate the 23 wards into six larger cities for efficiency purposes, and an agreement was reached between the metropolitan and special ward governments in 2006 to consider realignment of the wards, but there has been minimal further movement to change the current special ward system.[3]

In other prefectures

Special wards do not currently exist outside Tokyo; however, several Osaka area politicians, led by Governor Tōru Hashimoto, are backing an Osaka Metropolis plan under which the city of Osaka would be replaced by special wards, consolidating many government functions at the prefectural level and devolving other functions to more localized governments. Under a new 2012 law, – sometimes informally called "Osaka Metropolis plan law", but not specifically referring to Osaka – major cities and their surrounding municipalities in prefectures other than Tokyo may be replaced with special wards with similar functions if approved by the involved municipal and prefectural governments and ultimately the citizens of the dissolving municipalities in a referendum. Prerequisite is a population of at least 2 million in the dissolving municipalities; three cities (Yokohama, Nagoya and Osaka) meet this requirement on their own, seven other major city areas can set up special wards if a designated city is joined by neighboring municipalities.[6] However, prefectures (道府県, -dō/-fu/-ken) where special wards are set up cannot style themselves metropolis (都, -to) as the Local Autonomy Law only allows Tokyo with that status.[7] In Osaka, a 2015 referendum to replace the city with five special wards was defeated narrowly.

| Level | Executive | Executive leadership | Legislature |

|---|---|---|---|

| State/nation (kuni, 国) Unitary state, local autonomy anchored in the Constitution |

Central/Japanese national government (chūō-/Nihonkoku-seifu, 中央/日本国政府) |

Cabinet/Prime Minister (naikaku/naikaku sōri-daijin, 内閣/内閣総理大臣) indirectly elected by the Diet from the Diet |

National Diet (Kokkai, 国会) bicameral, both houses directly elected |

| Prefectures ("Metropolis, prefecture, prefectures and prefectures")[8] (to/dō/fu/ken, 都道府県) 47 contiguous subdivisions of the nation |

Prefectural/"Metropolitan" government (to-/dō-/fu-/kenchō, 都道府県庁) local autonomy and delegated functions from national level |

Prefectural/"Metropolitan" governor (to-/dō-/fu-/ken-chiji, 都道府県知事) directly elected |

Prefectural/"Metropolitan" assembly (to-/dō-/fu-/ken-gikai, 都道府県議会) unicameral, directly elected |

| [Subprefectures] (various names) Sub-prefectural administrative divisions of some prefectures, contiguous in some prefectures, only partial for some areas in others in Tokyo: 4 subprefectures for remote islands |

Branch office (shichō, 支庁 and other various names) (Subordinate branch offices of the prefectural government, delegated prefectural functions) | ||

| Municipalities (Cities, [special] wards/"cities", towns and villages) (shi/[tokubetsu-]ku/chō [=machi]/son [=mura], 市区町村) (as of 2016: 1,741) contiguous subdivisions of all 47 prefectures in Tokyo often named in the order: -ku/-shi/-chō/-son, 区市町村 in Tokyo as of 2001: 62 municipalities (23 special wards, 26 cities, 5 towns, 8 villages) |

Municipal government (city/ward/town/village hall) (shi-/ku-yakusho, 市/区役所/machi-/mura-yakuba, 町/村役場) local autonomy and delegated functions from national & prefectural level post-occupation–2000: only shi/chō/son with municipal autonomy rights, ku with delegated authority |

Municipal (city/ward/town/village) mayor (shi-/ku-/chō-/sonchō, 市区町村長) directly elected in Tokyo's special wards: indirectly elected 1952–1975 |

Municipal (city/ward/town/village) assembly (shi-/ku-/chō-/son-gikai, 市区町村議会) unicameral, directly elected |

| [Wards, sometimes unambiguously "administrative wards"] ([gyōsei-]ku, [行政]区) Contiguous sub-municipal administrative divisions of designated major cities |

Ward office (kuyakusho, 区役所) (Subordinate branch offices of the city government, delegated municipal functions) | ||

List of special wards

| No. | Flag | Name | Kanji | Population (as of October 2020)[9] |

Density (/km2) |

Area (km2) |

Major districts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Chiyoda | 千代田区 | 66,680 | 5,718 | 11.66 | Nagatachō, Kasumigaseki, Ōtemachi, Marunouchi, Akihabara, Yūrakuchō, Iidabashi, Kanda | |

| 02 | Chūō | 中央区 | 169,179 | 16,569 | 10.21 | Nihonbashi, Kayabachō, Ginza, Tsukiji, Hatchōbori, Tsukishima | |

| 03 | Minato | 港区 | 260,486 | 12,787 | 20.37 | Odaiba, Shinbashi, Hamamatsuchō, Mita, Toranomon, Azabu, Roppongi, Akasaka, Aoyama | |

| 04 | Shinjuku | 新宿区 | 349,385 | 19,175 | 18.22 | Shinjuku, Takadanobaba, Ōkubo, Waseda, Kagurazaka, Ichigaya, Yotsuya | |

| 05 | Bunkyō | 文京区 | 240,069 | 21,263 | 11.29 | Hongō, Yayoi, Hakusan | |

| 06 | Taitō | 台東区 | 211,444 | 20,914 | 10.11 | Ueno, Asakusa | |

| 07 | Sumida | 墨田区 | 272,085 | 19,759 | 13.77 | Kinshichō, Ryōgoku, Oshiage | |

| 08 | Kōtō | 江東区 | 524,310 | 13,055 | 40.16 | Kameido, Ojima, Sunamachi, Tōyōchō, Kiba, Fukagawa, Toyosu, Ariake | |

| 09 | Shinagawa | 品川区 | 422,488 | 18,497 | 22.84 | Shinagawa, Gotanda, Ōsaki, Hatanodai, Ōimachi, Tennōzu | |

| 10 | Meguro | 目黒区 | 288,088 | 19,637 | 14.67 | Meguro, Nakameguro, Jiyugaoka, Komaba, Aobadai | |

| 11 | Ōta | 大田区 | 748,081 | 12,332 | 60.66 | Ōmori, Kamata, Haneda, Den-en-chōfu | |

| 12 | Setagaya | 世田谷区 | 943,664 | 16,256 | 58.05 | Shimokitazawa, Kinuta, Karasuyama, Tamagawa | |

| 13 | Shibuya | 渋谷区 | 243,883 | 16,140 | 15.11 | Shibuya, Ebisu, Harajuku, Daikanyama, Hiroo | |

| 14 | Nakano | 中野区 | 344,880 | 22,121 | 15.59 | Nakano | |

| 15 | Suginami | 杉並区 | 591,108 | 17,354 | 34.06 | Kōenji, Asagaya, Ogikubo | |

| 16 | Toshima | 豊島区 | 301,599 | 23,182 | 13.01 | Ikebukuro, Komagome, Senkawa, Sugamo | |

| 17 | Kita | 北区 | 355,213 | 17,234 | 20.61 | Akabane, Ōji, Tabata | |

| 18 | Arakawa | 荒川区 | 217,475 | 21,405 | 10.16 | Arakawa, Machiya, Nippori, Minamisenju | |

| 19 | Itabashi | 板橋区 | 584,483 | 18,140 | 32.22 | Itabashi, Takashimadaira | |

| 20 | Nerima | 練馬区 | 752,608 | 15,653 | 48.08 | Nerima, Ōizumi, Hikarigaoka | |

| 21 | Adachi | 足立区 | 695,043 | 13,052 | 53.25 | Ayase, Kitasenju, Takenotsuka | |

| 22 | Katsushika | 葛飾区 | 453,093 | 13,019 | 34.80 | Tateishi, Aoto, Kameari, Shibamata | |

| 23 | Edogawa | 江戸川区 | 697,932 | 13,986 | 49.90 | Kasai, Koiwa | |

| Overall | 9,733,276 | 15,724 | 618.8 | ||||

Notable districts

Many important districts are located in Tokyo's special wards:

- Akasaka

- A district with a range of restaurants, clubs and hotels; many pedestrian alleys giving it a local neighbourhood feel. Next to Roppongi, Nagatachō, and Aoyama.

- Akihabara

- A densely arranged shopping district popular for electronics, anime culture, amusement arcades and otaku goods.[10]

- Aoyama

- A neighborhood of Tokyo adjacent to Omotesando with parks, trendy cafes, and international restaurants.

- Asakusa

- A cultural center of Tokyo, famous for the Sensō-ji Buddhist temple, and several traditional shopping streets. For most of the twentieth century, Asakusa was the main entertainment district in Tokyo, with large theaters, cinemas, an amusement park and a red light district. The area was heavily damaged by US bombing raids during World War II, and has now been rivaled by newer districts in the west of the city as entertainment and commercial centers.

- Ginza and Yūrakuchō

- Major shopping and entertainment district with historic department stores, upscale shops selling brand-name goods, and movie theaters. This area is part of the original city center in the wards of Chuo and Chiyoda (as opposed to the new centers in Shinjuku, Ikebukuro, and Shibuya).

- Harajuku

- Known internationally for its role in Japanese street fashion.

- Ikebukuro

- The busiest interchange in north central Tokyo, featuring Sunshine City and various shopping destinations.

- Jinbōchō

- Tokyo's center of used-book stores and publishing houses, and a popular antique and curio shopping area.

- Kasumigaseki

- Home to most of the executive offices of the national government, as well as the Tokyo Metropolitan Police.

- Marunouchi and Ōtemachi

- As one of the main financial and business districts of Tokyo, Marunouchi includes the headquarters of many banks, trading companies and other major corporations. The area is seeing a major redevelopment in the near future with plans for new buildings and skyscrapers for shopping and entertainment constructed on the Marunouchi side of Tokyo Station. This area is part of the original city center in the wards of Chuo and Chiyoda (as opposed to the new centers in Shinjuku, Ikebukuro, and Shibuya).

- Nagatachō

- The political heart of Tokyo and the nation. It is the location of the National Diet (parliament), government ministries, and party headquarters.

- Odaiba

- A large, reclaimed, waterfront area that has become one of Tokyo's most popular shopping and entertainment districts.

- Omotesandō

- Known for upscale shopping, fashion, and design

- Roppongi

- Home to the rich Roppongi Hills area, Mori Tower, an active night club scene, and a relatively large presence of Western tourists and expatriates.

- Ryōgoku

- The heart of the sumo world. Home to the Ryōgoku Kokugikan and many sumo stables.

- Shibuya

- A long-time center of shopping, fashion, nightlife and youth culture. Shibuya is a famous and popular location for photographers and tourists.

- Shinagawa

- In addition to the major hotels on the west side of Shinagawa Station, the former "sleepy east side of the station" has been redeveloped as a major center for business.[11] Shinagawa station is in Minato-ku, not in Shinagawa-ku.

- Shinbashi

- A traditional Shitamachi district, recently revitalized by being the gateway to Odaiba and the Shiodome Shiosite complex of high-rise buildings.

- Shinjuku

- Location of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Building, and a major secondary center of Tokyo (fukutoshin), as opposed to the original center in Marunouchi and Ginza. The area is known for its concentration of skyscrapers and shopping areas. Major department stores, electronics stores and hotels are located here. On the east side of Shinjuku Station, Kabukichō is known for its many bars and nightclubs. Shinjuku Station moves an estimated three million passengers a day, which makes it the busiest rail station in the world.

- Ueno

- Ueno is known for its parks, department stores, and large concentration of cultural institutions. Ueno Zoo and Ueno Park are located here. Ueno Station is a major transportation hub serving commuters to and from areas north and east of Tokyo. In the spring, the area is a popular locale to view cherry blossoms.

See also

References

- ↑ Tokyo Metropolitan Government: "Municipalities Within Tokyo" Archived 2017-12-13 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "TMG and the 23 Special Wards". Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- 1 2 河尻, 定 (27 March 2015). "ごみ・税金… 東京23区は境界またげばこんなに違う". Nihon Keizai Shimbun. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Kurt Steiner, Local government in Japan, Stanford University Press, 1965, p. 179

- ↑ 2010 population XLS

- ↑ Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications: 大都市地域における特別区の設置に関する法律(平成24年法律第80号)概要 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 1–3; Full text Archived 2017-08-01 at the Wayback Machine in the e-gov legal database

- ↑ CLAIR (Jichitai Kokusaika Kyōkai), Japan Local Government Centre, London, August 31, 2012: New law for Japanese megacities Archived 2017-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ GSI: Toponymic guidelines for Map Editors and other Editors, JAPAN (Third Edition 2007) in English, 5. Administrative divisions Archived 2017-07-28 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Population by District". Tokyo Statistical Yearbook. Archived from the original on 2022-09-30. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- ↑ "The best places for shopping in Tokyo" Archived 2023-01-30 at the Wayback Machine, Meet The Cities

- ↑ 日本経済新聞社・日経BP社. "品川新駅再開発に着手 JR東、民営化30年目の挑戦|オリパラ|NIKKEI STYLE". NIKKEI STYLE (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2017-09-13. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

Further reading

- Jacobs, A. J. (3 January 2011). "Japan's Evolving Nested Municipal Hierarchy: The Race for Local Power in the 2000s". Urban Studies Research. 2011: e692764. doi:10.1155/2011/692764. ISSN 2090-4185.

- Historical Development of Japanese Local Governance. The Institute for Comparative Studies in Local Governance. Archived from the original on 2013-06-12.

- Ohsugi, S. (2011). "Large City System of Japan" (PDF). Papers on the Local Governance System and Its Implementation in Selected Fields in Japan (20): 1.

graphic shows special wards of Tokyo compared with other Japanese city types at p. 1 (PDF: 7 of 40)

- "索引検索結果画面" [Text of the Local Government Law] (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2005-02-05.