The speech-to-song illusion is an auditory illusion discovered by Diana Deutsch in 1995. A spoken phrase is repeated several times, without altering it in any way, and without providing any context. This repetition causes the phrase to transform perceptually from speech into song.[1][2]

Discovery and first experiment

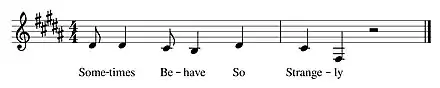

The illusion was discovered by Deutsch in 1995 when she was preparing the spoken commentary on her CD ‘Musical Illusions and Paradoxes'. She had the phrase ‘sometimes behave so strangely' on a loop, and noticed that after it had been repeated several times it appeared to be sung rather than spoken.[1] Later she included this illusion on her CD ‘Phantom Words and other Curiosities'[2] and noted that once the phrase had perceptually morphed into song, it continued to be heard as song when played in the context of the full sentence in which it occurred.

Deutsch, Henthorn, and Lapidis[3][4] examined the illusion in detail. They showed that when this phrase was heard only once, listeners perceived it as speech, but after several repetitions, they perceived it as song. This perceptual transformation required that the intervening repetitions be exact; it did not occur when they were transposed slightly, or presented with the syllables in jumbled orderings. In addition, when listeners were asked to repeat back the phrase after hearing it once, they repeated it back as speech. Yet when they were asked to repeat back the phrase after hearing it ten times, they repeated it back as song.

Neurological substrates of the illusion

Theories of the neurological substrates of speech and song perception have been based on responses to speech and song stimuli, and these differ in their features. For example, the pitch content within spoken syllables generally changes dynamically, while the pitches of musical notes tend to be stable and the notes tend to be of longer duration. For this reason, theories of the brain substrates of speech and song perception have invoked explanations in terms of the acoustic features involved.[5] Yet in the speech-to-song illusion a phrase is repeated exactly, with no change in its features; however, it can be heard either as speech or as song. For this reason, several studies have explored the brain regions that are involved in the illusion. Increased activation has been found in the frontal and temporal lobes of both hemispheres when the listener was perceiving a repeated spoken phrase as sung rather than spoken.[6][7] The activated regions included several that other researchers had found to be activated while listening to song.[8][9]

Speech material conducive to the illusion

Phrases that are marked by syllables with stable pitches and that favor a metrical interpretation tend to be conducive to the illusion.[6][10] However, the illusion is not enhanced by regular repetitions of the entire phrase.[10][11] Further, the illusion is stronger for phrases in languages that are more difficult to pronounce[11] and when listeners are unable to understand the language of the utterance.[12]

Listeners who experience the illusion

The speech-to-song illusion occurs in listeners both with and without musical training.[6][3][4][7][10][11][12] It occurs in listeners who speak different languages, including the non-tone languages English, Irish, Catalan, German, Italian, Portuguese, French, Croatian, and Hindi, and the tone languages Thai and Mandarin; however, it is weaker in speakers of tone languages than non-tone languages.[11][12]

Related illusions

Margulis and Simchi-Gross have reported related illusions in which different types of sound are transformed into music by repetition. Random sequences of tones were heard as more musical when they were looped,[13] and clips consisting of a mix of environmental sounds sounded more musical following repetition.[14] These effects were weaker than that of the original speech-to-song illusion, perhaps because speech and song are particularly intertwined perceptually, and also because the characteristics of the speech producing the original illusion are particularly conducive to a strong effect.

Explanations of the illusion

Repetition is a particularly important characteristic of music, and so provides an important cue that a phrase should be considered as music rather than speech.[15][16] More specifically, in song, the pitches of vowels are distinctly heard, but in speech they appear watered down. It has been suggested that in speech the neural circuitry underlying pitch perception is somewhat inhibited, enabling the listener to focus attention on consonants and vowels, which are important to verbal meaning. Exact repetition of spoken words may cause this circuitry to become disinhibited, so that pitches are heard more saliently, and so as sung.[16] Indeed, the brain structures that are activated when the illusion occurs correspond largely to those that are activated in response to song.[6][8][9]

In addition, several features of a spoken phrase that are likely to occur in song are conducive to the illusion. These include syllables with more stable pitches, and phrases with more regular distributions of accents.[10] Other explanations invoke higher-level musical structure and memory. Listeners are better able to discriminate pitches in repeated rather than unrepeated phrases when the pitches violate the structure Western of tonal music.[17] Long term memory for melodies may also be involved: If the prosodic features of a spoken phrase are similar to those of a well-known melody, the brain circuitries underlying musical pitch patterns and rhythms can be invoked, so that the phrase is heard as song.[16]

Relationship to musical composition

Many composers, including Gesualdo, Monteverdi, and Mussorgsky, have argued that expressivity in music can be derived from inflections in speech, and they have included features of speech in their music.[16] Another relationship was invoked by Steve Reich, in his compositions such as Come Out and It's Gonna Rain. He presented spoken phrases in stereo and looped them, gradually offsetting the sounds from the two sources so as to create musical effects, and these were enhanced as the discrepancy widened.[18][19] Further, in Reich’s composition Different Trains brief excerpts of speech were embedded in instrumental music so as to bring out their musical quality.[20] Today, much popular music, particularly rap music, consists of chanting rhythmic speech with musical accompaniment.

References

- 1 2 Diana Deutsch (1995). Musical Illusions and Paradoxes, Track 1 (CD). La Jolla: Philomel Records. 1377600012.

- 1 2 Diana Deutsch (2003). Phantom Words and Other Curiosities, Tracks 21-26 (CD). La Jolla: Philomel Records. 1377600022.

- 1 2 Deutsch, D.; Henthorn, T.; Lapidis, R. (2008). "The speech-to-song illusion". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 124 (4): 2471. Bibcode:2008ASAJ..124.2471D. doi:10.1121/1.4808987.

- 1 2 Deutsch, D.; Henthorn, T.; Lapidis, R. (2011). "Illusory transformation from speech to song". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 129 (4): 2245–2252. Bibcode:2011ASAJ..129.2245D. doi:10.1121/1.3562174. PMID 21476679.

- ↑ Zatorre, R. J.; Belin, P.; Penhune, V. B. (2002). "Structure and function of auditory cortex: music and speech". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 6 (1): 37–46. doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01816-7. PMID 11849614. S2CID 3076176.

- 1 2 3 4 Tierney, A.; Dick, F.; Deutsch, D.; Sereno, M. (2013). "Speech versus song: multiple pitch-sensitive areas revealed by a naturally occurring musical illusion". Cerebral Cortex. 23 (2): 249–254. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhs003. PMC 3539450. PMID 22314043.

- 1 2 Hymers , M.; Prendergast , G.; Liu, C.; Schulze, A.; Young, M. L.; Wastling, S. J.; Barker , G. J.; Millman, R. E. (2015). "Neural mechanisms underlying song and speech perception can be differentiated using an illusory percept". NeuroImage. 108: 225–233. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.010. PMID 25512041.

- 1 2 Callan, D.; Tsytsarev, V.; Hanakawa, T.; Callan, A.; Katsuhara M.; Fukuyama, H.; Turner, R. (2006). "Song and speech: brain regions involved with perception and covert production". NeuroImage. 31 (3): 1327–1342. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.036. PMID 16546406. S2CID 12480888.

- 1 2 Schön, D.; Gordon, R.; Campagne, A.; Magne, C.; Astésano C.; Anton, J.; Besson, M. (2010). "Similar cerebral networks in language, music and song perception". NeuroImage. 51 (1): 450–461. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.02.023. PMID 20156575. S2CID 6386437.

- 1 2 3 4 Falk, S.; Rathcke, T.; Dalla Bella, S. (2014). "When speech sounds like music". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 40 (4): 1491–1506. doi:10.1037/a0036858. PMID 24911013. S2CID 2380724.

- 1 2 3 4 Margulis, E. H.; Simchy-Gross, R.; Black, J. L. (2015). "Pronunciation difficulty, temporal regularity, and the speech-to-song illusion". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 48. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00048. PMC 4310215. PMID 25688225.

- 1 2 3 Jaisin, K.; Suphanchaimat, R.; Figueroa, M. A. F. C.; Warren, J. D. (2016). "The speech-to-song illusion is reduced in speakers of tonal (vs. non-tonal) languages". Frontiers in Psychology. May: 662. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00662. PMC 4860502. PMID 27242580.

- ↑ Margulis, E. H.; Simchi-Gross, R. (2016). "Repetition enhances the musicality of randomly generated tone sequences". Music Perception. 33 (4): 509–514. doi:10.1525/MP.2016.33.4.509.

- ↑ Simchi-Gross, R.; Margulis, E. H. (2018). "The sound-to music illusion: Repetition can musicalize nonspeech sounds". Music and Science. doi:10.1177/2059204317731992.

- ↑ Margulis, E.H. (2014). On repeat: How music plays the mind. New York: Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 3 4 Deutsch, D. (2019). Musical Illusions and Phantom Words: How Music and Speech Unlock Mysteries of the Brain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190206833. LCCN 2018051786.

- ↑ Vanden Bosch der Nederlanden, C.; Hannon, E.E.; Snyder, J.S. (2015). "Finding the music of speech: Musical knowledge influences pitch processing in speech". Cognition. 142: 135–140. doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2015.06.015. PMID 26151370.

- ↑ Steve Reich (1966). Come Out. Columbia Records, a division of Sony Music Entertainment.

- ↑ Steve Reich (1965). It’s Gonna Rain. Nonesuch.

- ↑ Steve Reich (1988). Different Trains. Nonesuch.

Further reading

- Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis (2013). On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199990825.

- Deutsch, D. (2019). Musical Illusions and Phantom Words: How Music and Speech Unlock Mysteries of the Brain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190206833. LCCN 2018051786.

External links

- "Behaves So Strangely" Interview with Jad Abrumrad, Radiolab, WNYC Studios, 2007, September

- "Sounds sometimes behave so strangely" Interview with Georgia Mills, Naked Scientists, BBC Radio and ABC Radio, 2018, April

- "Auditory Illusions", BBC Radio 4, 2019, August

- "Diana Deutsch's Speech-to-Song Illusion site

- "Sometimes behaves so strangely", Metafilter, 2019, September

- "How often does speech turn into song?", Esther Inglis-Arkell, Gizmodo, 2014, March.