| Sphagnum australe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Loose hummock with a thick stem, broad flat stem leaves and small leaflet protrusions | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Bryophyta |

| Class: | Sphagnopsida |

| Order: | Sphagnales |

| Family: | Sphagnaceae |

| Genus: | Sphagnum |

| Species: | S. australe |

| Binomial name | |

| Sphagnum australe Mitt. | |

Sphagnum australe is a species of Sphagnum found in southeastern Australia.

S. australe is very hard to differentiate from other species of sphagnum moss, particularly S. compactum (some forms with short internodes particularly) however the distance along the stems between the fascicles (the bundles of structures) on branches are very variable.[1]

Etymology

Sphagnum in Latin means moss (sphagnos) with the first known use in 1741.[2] "australe" originates from austral, a Meridionale (Southern Italy) word meaning southern or south or southerner.[3]

Habitat

Sphagnum australe is a moss found in Australia with known locations from New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory, Victoria through to Tasmania.[4] S. Australe grows in wet soil, forming extensive mounds in areas of shaded water seepage or of swampy ground. Sphagnum australe grows at an elevation of 0–1,239 m (0–4,065 ft).[4] This species of is predominantly found on extensive colonies of alpine or sub-alpine bogs. Some can be found at much lower altitude occasionally in places almost down at sea level but these are much smaller areas.[5]

Sphagnum australe structure

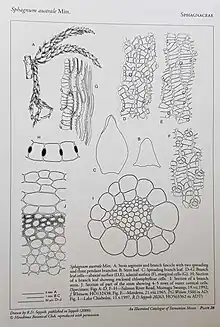

Sphagnum australe's anatomy involves a main stem segment and a branch fascicle which is a bunch of tightly arranged structures (usually two or three), with two spreading branches and three pendant branches,[4] hanging downwards. The top of the moss, the capitulum (a rounded protruding top of the plant), has a tuft like appearance with a cluster of tiny young branches of younger growth. There are leaves of various size and spacing down the stem. The stem leaves are smaller than the spreading branch leaves. Branch leaf cells are clustered and have cells containing chlorophyll which are important for photosynthesis.

Reproduction

Reproduction of Sphagnum australe is exhibited through the typical alternation of generations found in other mosses. Because they have a haploid (single set of chromosomes in cells) gametophyte, their gametes are relatively large and long-lived and noticeable on the plant (compared to the smaller and shorter lived diploid sphorophytes that are produced on the gametophytes.[6] These sphorophytes produce spores and then is shed from gametophyte. The gametophyte is the sexual phase of the life cycle of plants and algae. Sex organs are produced on this structure that then produce gametes and haploid sex cells participating in fertilisation and then forming a diploid zygote which has the double set of chromosomes. Typically on moss it is a separate structure on the plant. In S. australe, dark brown circular sporophytes can be seen.

Ecological importance

Sphagnum is of ecological importance because of the peat bogs they form. These peat bogs serve as a carbon sink in the ecosystem.[7] Sphagnum is a photosynthetic autotroph meaning it makes its food (in the form of carbohydrates) through photosynthesis, a process driven by light energy where it is converted to chemical energy in the form of sugars which are constructed from water and carbon dioxide with oxygen released as a byproduct. Sphagnum then uses the carbohydrate material produced as energy for metabolic activity and to make biomolecules.[6] Photosynthetic autotrophs are important because they produce their own food with the organic waste. Because they are primary producers they form a base for our ecosystem and fuel the next levels on the trophic scale such as animals who rely on plants for food and oxygen production.[8]

Sphagnum bogs are small in Australia with a limited distribution but have a high conservation value due to creating cool, wet environments that are typically fire free or restricted. They are therefore poorly adapted to recover from fire so are of high conservation consideration.[9] Sphagnum bogs and the associated fern communities are currently listed as endangered,[10] predominantly due to the inability to recover fully from fire.

Sphagnum absorbs a vast quantity of water during heavy downpours or snowmelts and will then release much of that water in a more gradual flow over a much longer period. The water in Sphagnum bogs is highly acidic, nutrient-poor and has a low oxygen content. Many other organisms cannot tolerate these conditions including decay bacteria which creates an environment that can preserve organic matter quite well.[5] Other plant species that can survive sphagnum bogs include the prickly heath species of the family Epacridaceae as well as sedges, grasses and daisy flowers which help to create a rich plant community supporting a wide variety of wildlife, such as frogs,[5] and the unique ecosystem.

Sphagnum moss has had many uses historically, especially commercially but also medically; particularly during World War I, masses of the dehydrated moss were used as surgical dressings.

References

- ↑ Seppelt, Rodney D. (2012). "Australian Mosses Online. 52. Spagnaceae" (PDF). Australian Mosses Online.

- ↑ "Definition of SPHAGNUM". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ↑ "Translation of australe - Italian-English dictionary". Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- 1 2 3 Rod D. Seppelt; S. Jean Jarman; Lyn H. Cave; Paddy J. Dalton (2013). An Illustrated Catalogue of Tasmanian Mosses Part 1. Hobart: Tasmanian Herbarium. pp. 70–71, Plate 28. ISBN 978-4-18-700281-1.

- 1 2 3 Australian National Botanic Gardens, Parks Australia. "The Plant Underworld - Australian Plant Information". www.anbg.gov.au. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- 1 2 Briggs, George M. (2021). "Sphagnum-peat moss". Inanimate Life.

- ↑ "Sphagnum: Classification, Structure and Reproduction". BYJUS. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

- ↑ "Photosynthesis". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ↑ Prior, Lynda D.; Nichols, Scott C.; Williamson, Grant J.; Bowman, David M. J. S. (March 2023). "Post‐fire restoration of Sphagnum bogs in the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area, Australia". Restoration Ecology. 31 (3). doi:10.1111/rec.13797. ISSN 1061-2971. S2CID 252449811.

- ↑ Jeffery, Michael I.; Firestone, Jeremy; Bubna-Litic, Karen, eds. (2008), "Sanctuaries, Protected Species, and Politics – How Effective Is Australia at Protecting Its Marine Biodiversity under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999?", Biodiversity Conservation, Law + Livelihoods, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 280–305, doi:10.1017/cbo9780511551161.018, ISBN 9780511551161, retrieved 2023-11-13