In physics, a spherical pendulum is a higher dimensional analogue of the pendulum. It consists of a mass m moving without friction on the surface of a sphere. The only forces acting on the mass are the reaction from the sphere and gravity.

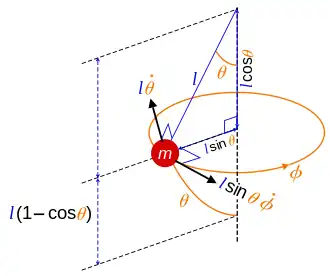

Owing to the spherical geometry of the problem, spherical coordinates are used to describe the position of the mass in terms of , where r is fixed such that .

Lagrangian mechanics

Routinely, in order to write down the kinetic and potential parts of the Lagrangian in arbitrary generalized coordinates the position of the mass is expressed along Cartesian axes. Here, following the conventions shown in the diagram,

- .

Next, time derivatives of these coordinates are taken, to obtain velocities along the axes

- .

Thus,

and

The Lagrangian, with constant parts removed, is[1]

The Euler–Lagrange equation involving the polar angle

gives

and

When the equation reduces to the differential equation for the motion of a simple gravity pendulum.

Similarly, the Euler–Lagrange equation involving the azimuth ,

gives

- .

The last equation shows that angular momentum around the vertical axis, is conserved. The factor will play a role in the Hamiltonian formulation below.

The second order differential equation determining the evolution of is thus

- .

The azimuth , being absent from the Lagrangian, is a cyclic coordinate, which implies that its conjugate momentum is a constant of motion.

The conical pendulum refers to the special solutions where and is a constant not depending on time.

Hamiltonian mechanics

The Hamiltonian is

where conjugate momenta are

and

- .

In terms of coordinates and momenta it reads

Hamilton's equations will give time evolution of coordinates and momenta in four first-order differential equations

Momentum is a constant of motion. That is a consequence of the rotational symmetry of the system around the vertical axis.

Trajectory

Trajectory of the mass on the sphere can be obtained from the expression for the total energy

by noting that the horizontal component of angular momentum is a constant of motion, independent of time.[1] This is true because neither gravity nor the reaction from the sphere act in directions that would affect this component of angular momentum.

Hence

which leads to an elliptic integral of the first kind[1] for

and an elliptic integral of the third kind for

- .

The angle lies between two circles of latitude,[1] where

- .

See also

References

Further reading

- Weinstein, Alexander (1942). "The spherical pendulum and complex integration". The American Mathematical Monthly. 49 (8): 521–523. doi:10.1080/00029890.1942.11991275.

- Kohn, Walter (1946). "Contour integration in the theory of the spherical pendulum and the heavy symmetrical top". Transactions of the American Mathematical Society. 59 (1): 107–131. doi:10.2307/1990314. JSTOR 1990314.

- Olsson, M. G. (1981). "Spherical pendulum revisited". American Journal of Physics. 49 (6): 531–534. Bibcode:1981AmJPh..49..531O. doi:10.1119/1.12666.

- Horozov, Emil (1993). "On the isoenergetical non-degeneracy of the spherical pendulum". Physics Letters A. 173 (3): 279–283. Bibcode:1993PhLA..173..279H. doi:10.1016/0375-9601(93)90279-9.

- Richter, Peter H.; Dullin, Holger R.; Waalkens, Holger; Wiersig, Jan (1996). "Spherical pendulum, actions and spin". J. Phys. Chem. 100 (49): 19124–19135. doi:10.1021/jp9617128. S2CID 18023607.

- Shiriaev, A. S.; Ludvigsen, H.; Egeland, O. (2004). "Swinging up the spherical pendulum via stabilization of its first integrals". Automatica. 40: 73–85. doi:10.1016/j.automatica.2003.07.009.

- Essen, Hanno; Apazidis, Nicholas (2009). "Turning points of the spherical pendulum and the golden ratio". European Journal of Physics. 30 (2): 427–432. Bibcode:2009EJPh...30..427E. doi:10.1088/0143-0807/30/2/021. S2CID 121216295.

- Dullin, Holger R. (2013). "Semi-global symplectic invariants of the spherical pendulum". Journal of Differential Equations. 254 (7): 2942–2963. arXiv:1108.4962. Bibcode:2013JDE...254.2942D. doi:10.1016/j.jde.2013.01.018.