| Steels |

|---|

|

| Phases |

| Microstructures |

| Classes |

| Other iron-based materials |

Ductile iron, also known as ductile cast iron, nodular cast iron, spheroidal graphite iron, spheroidal graphite cast iron[1] and SG iron, is a type of graphite-rich cast iron discovered in 1943 by Keith Millis.[2] While most varieties of cast iron are weak in tension and brittle, ductile iron has much more impact and fatigue resistance, due to its nodular graphite inclusions.

On October 25, 1949, Keith Dwight Millis, Albert Paul Gagnebin and Norman Boden Pilling received US patent 2,485,760 on a cast ferrous alloy for ductile iron production via magnesium treatment.[3] Augustus F. Meehan was awarded a patent in January 1931 for inoculating iron with calcium silicide to produce ductile iron subsequently licensed as Meehanite, still produced as of 2017.

Metallurgy

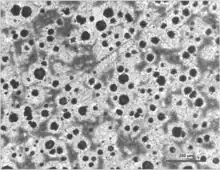

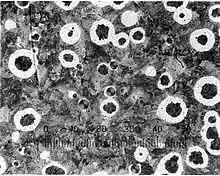

Ductile iron is not a single material but part of a group of materials which can be produced with a wide range of properties through control of their microstructure. The common defining characteristic of this group of materials is the shape of the graphite. In ductile irons, graphite is in the form of nodules rather than flakes as in grey iron. Whereas sharp graphite flakes create stress concentration points within the metal matrix, rounded nodules inhibit the creation of cracks, thus providing the enhanced ductility that gives the alloy its name.[5] Nodule formation is achieved by adding nodulizing elements, most commonly magnesium (magnesium boils at 2012F and iron melts at 2732F and, less often now, cerium (usually in the form of mischmetal).[6] Tellurium has also been used. Yttrium, often a component of mischmetal, has also been studied as a possible nodulizer.

Austempered ductile iron (ADI; i.e., austenite tempered[7]) was discovered in the 1950s but was commercialized and achieved success only some years later. In ADI, the metallurgical structure is manipulated through a sophisticated heat treating process.

Composition

| Fe | C | Si | Ni | Mn | Mg | Cr | P | S | Cu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balance | 3.0–3.7 | 1.2–2.3 | 1.0 | 0.25 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.1 | |

| Balance | 3.3–3.6 | 2.2–2.8 | 0.1-0.2 | 0.03–0.04 | 0.005–0.04 | 0.005–0.02 | <0.40 |

Elements such as copper or tin may be added to increase tensile and yield strength while simultaneously reducing ductility. Improved corrosion resistance can be achieved by replacing 15–30% of the iron in the alloy with varying amounts of nickel, copper, or chromium. Other ductile iron compositions often have a small amount of sulfur as well.

Silicon as a graphite formation element can be partially replaced by aluminum to provide better oxidation protection.[9]

Applications

Much of the annual production of ductile iron is in the form of ductile iron pipe, used for water and sewer lines. It competes with polymeric materials such as PVC, HDPE, LDPE and polypropylene, which are all much lighter than steel or ductile iron; being softer and weaker, these require protection from physical damage.

Ductile iron is specifically useful in many automotive components, where strength must surpass that of aluminum but steel is not necessarily required. Other major industrial applications include off-highway diesel trucks, class 8 trucks, agricultural tractors, and oil well pumps. In the wind power industry ductile iron is used for hubs and structural parts like machine frames. Ductile iron is suitable for large and complex shapes and high (fatigue) loads.

Ductile iron is used in many grand piano harps (the iron plates to which high-tension piano strings are attached).

Ductile iron is used for vises. Previously, regular cast iron or steel was commonly used. The properties of ductile iron make it a significant upgrade in strength and durability from cast iron without having to use steel, which is more expensive.

See also

References

- ↑ Smith & Hashemi 2006, p. 432.

- ↑ "Modern Casting, Inc". Archived from the original on 2004-12-14. Retrieved 2005-01-01.

- ↑ US patent 2485760, Keith Millis, "Cast Ferrous Alloy", issued 1949-10-25

- ↑ Yaqub, Ejaz; Arshad, Rizwan (2009). "ME-140 Workshop Technology - Slide 25" (images). Air University. Retrieved 2011-10-30.

- ↑ "Ductile Iron Data - Section 2". www.ductile.org. Archived from the original on 2001-01-29.

- ↑ Gillespie, LaRoux K. (1988), Troubleshooting manufacturing processes (4th ed.), SME, p. 4, ISBN 978-0-87263-326-1.

- ↑ "ADI the Material". ADI Treatments Ltd. Archived from the original on 2010-10-26. Retrieved 2010-01-24.

- ↑ ASTM International. A874/A874M-98(2018)e1 Standard Specification for Ferritic Ductile Iron Castings Suitable for Low-Temperature Service. West Conshohocken, PA; ASTM International, 2018. doi:10.1520/A0874_A0874M-98R18E01

- ↑ Aluminum ADI

Bibliography

- Smith, William F.; Hashemi, Javad (2006), Foundations of Materials Science and Engineering (4th ed.), McGraw-Hill, ISBN 0-07-295358-6.

- Erfanian-Naziftoosi, Hamid Reza (2012), "The Effect of Isothermal Heat Treatment Time on the Microstructure and Properties of 2.11% Al Austempered Ductile Iron", Journal of Materials Engineering and Performance, 21 (8): 1785–1792, Bibcode:2012JMEP...21.1785E, doi:10.1007/s11665-011-0086-y, S2CID 55925760.