Baked springerle, showing typical "foot" | |

| Type | Cookie |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Germany |

| Associated cuisine | Swabia, Bavaria, Bohemia, Switzerland, Austria, Alsace[1] |

| Main ingredients | Flour, sugar, egg, anise |

Springerle (German: [ˈʃpʁɪŋɐlə] ⓘ) is a type of South German biscuit or cookie with an embossed design made by pressing a mold onto rolled dough and allowing the impression to dry before baking. This preserves the detail of the surface pattern. While historical molds show that springerle were baked for religious holidays and secular occasions throughout the year, they are now most commonly associated with the Christmas season.[1][2]

They are called anis-brödle in the Swabian dialect,[3] and Anisbrötli (anise bun) in Switzerland.[4] The name springerle, used in southern Germany, translates literally as "little jumper" or "little knight", but its exact origin is unknown. It may refer the popular motif of a jumping horse in the mold, or just to the rising or "springing up" of the dough as it bakes.[1]

The origin of the cookie can be traced back to at least the 14th century in southwestern Germany and surrounding areas, mostly in Swabia.[1][5] One of the oldest surviving molds, held at the Swiss National Museum in Zürich, dates from the 14th century.[6]

Baking process

Raw springerle dough, just out of the wooden wedding-carriage mold (shown above)

Raw springerle dough, just out of the wooden wedding-carriage mold (shown above) Springerle dough after drying for a day

Springerle dough after drying for a day Baked springerle, showing typical "foot"

Baked springerle, showing typical "foot"

The major ingredients of springerle are eggs, white (wheat) flour, and very fine or powdered sugar. The biscuits are traditionally anise-flavored, although the anise is not usually mixed into the dough; instead it is dusted onto the baking sheets so that the biscuit sits on top of the crushed anise seeds.[1][6]

Traditional springerle recipes use hartshorn salt (ammonium carbonate, or baker's ammonia) as a leavening agent. Since hartshorn salt can be difficult to find, many modern recipes use baking powder as the leavening agent. Springerle made with hartshorn salt are lighter and softer than those made with baking powder. The hartshorn salt also imparts a crisper design and longer shelf-life to the springerle. The leavening causes the biscuit to at least double in height during baking.

To make springerle, very cold, stiff dough is rolled thin and pressed into a mold, or impressed by a specialized, carved rolling pin. The dough is unmolded and then left to dry for about 24 hours before being baked at a low temperature on greased, anise-dusted baking sheets.[6]

The drying period allows time for the pattern in the top of the cookie to set, so that the cookie has a "pop-up" effect from leavening, producing the characteristic "foot" along the edges, below the molded surface.

The baked biscuits are hard, and are packed away to ripen for two or four weeks. During this time, they become tender.[1]

Another method of making springerle is to not chill the dough at all. Commonly, after mixing all the ingredients together, one would cover a surface with flour, and use a regular rolling pin (also covered in flour) to roll out the dough to about half-an-inch of thickness. Flour would be spread over the top surface of the rolled-out dough, and also on the specialized Springerle rolling pin. One would whack the Springerle rolling pin against one's hand a few times, to dislodge any flour caked into the designs on it, and then proceed to carefully but firmly roll out the molds. One uses a knife to cut out the small, rectangular cookies (often 2x1 inches), and place them on a wooden board to dry overnight (or for at least twelve hours). As this process is repeated, the dough gets more brittle due to the added flour and doesn't hold the molds as well. Therefore, it is important to roll the dough out in small batches (instead of all at once), to keep the moisture in so the cookies hold together. Anise seed is sprinkled on the baking sheets just before putting them in the oven (about ten minutes is usually sufficient, but the cooking time also depends on thickness). 1-2 teaspoons of anise extract can also be added to the dough to increase the taste (which is rather like licorice), and the amount of cookies varies on the thickness. The usual recipe with 4 eggs and 3-4 cups of flour can yield anywhere from 60 to 144 cookies, depending on thickness and the experience of the maker.

Molds

Molds are traditionally carved from wood, although plastic and pottery molds are also available. Pear wood is prized for its density and durability. Older handmade molds are folk art, are typically unsigned, and undated. Many historic molds are held in museum collections as evidence of local cultures, as they include religious, secular, and other symbols, as well as revealing what aesthetics were valued at the time of their carving.[2]

The stamping technique may be derived from the molds used in some Christian traditions to mark sacramental bread, and the earliest molds featured religious motifs, including scenes from Bible stories and Christian symbols. Later, in the 17th and 18th century, heraldic themes of knights and fashionably dressed ladies became popular. Themes of happiness, love, weddings, and fertility remained popular through the 19th century.[1][7]

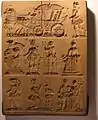

Springerle mold from the Landesmuseum Württemberg

Springerle mold from the Landesmuseum Württemberg This mold shows a wedding carriage and many figures.

This mold shows a wedding carriage and many figures. The back side of the same mold, showing more figures

The back side of the same mold, showing more figures

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Darra Goldstein, ed. (Apr 2015). The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. Oxford University Press.

- 1 2 Hudgins, Sharon (2004-11-01). "Edible Art: Springerle Cookies". Gastronomica. 4 (4): 66–71. doi:10.1525/gfc.2004.4.4.66. ISSN 1529-3262.

- ↑ "German Recipe: Springerle traditional holiday art in cookie form". Stuttgart Citizen. US Army Garrison Stuttgart Public Affairs Office. 4 December 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ↑ Rüther, Manuela (2010-12-16). "Weihnachtsgebäck: Springerle, edles Plätzchen und leckere Visitenkarte". DIE WELT (in German). Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ↑ Anikó, Samu-Kuschatka. "History of Springerle". andallthekingsmen.bizhosting.com. And All The King's Men. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 Cusick, Marie (December 24, 2011). "Medieval Christmas Cookies Still In Fashion". National Public Radio. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ↑ "Springerle History". www.sweetoothdesign.com. Sweet Tooth Design. Archived from the original on 2014-10-18. Retrieved 19 October 2014.