Srebrenica

Сребреница | |

|---|---|

Town and municipality | |

View of Srebrenica (2005) | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

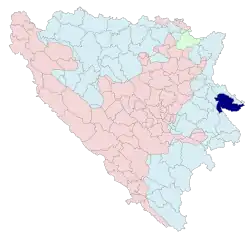

Location of Srebrenica within Republika Srpska | |

| |

| Coordinates: 44°06′15″N 19°17′50″E / 44.10417°N 19.29722°E | |

| Country | |

| Entity | |

| Geographical region | Podrinje |

| Boroughs | 81 |

| Government | |

| • Municipal mayor | Mladen Grujičić (SNSD) |

| Area | |

| • Town | 2.62 km2 (1.01 sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 529.83 km2 (204.57 sq mi) |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Town | 2,607 |

| • Town density | 1,000/km2 (2,600/sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 13,409 |

| • Municipality density | 25/km2 (66/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | 56 |

| Website | www |

Srebrenica (Serbian Cyrillic: Сребреница, pronounced [srêbrenitsa]) is a town and municipality in the easternmost part of Bosnia and Herzegovina, located in Republika Srpska entity. It is a small mountain town, with its main industry being salt mining and a nearby spa. As of 2013, the town has a population of 2,607 inhabitants, while the municipality has 13,409 inhabitants.

During the Bosnian War in 1995, Srebrenica was the site of a massacre of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys, which was subsequently designated as an act of genocide by the ICTY and the International Court of Justice.

History

Roman era

Illyrians inhabited Srebrenica and mined the silver in a nearby mine. Silver was also the main reason behind the Roman invasion of the area.[1]

During the Roman times, there was a settlement of Domavia, known to have been near a mine.[2][3] Silver ore from there was moved to the mints in Salona in the southwest and Sirmium in the northeast using the Via Argentaria.[4] The current settlement of Srebrenica was also known by the Romans as Argentaria.[5]

A Roman tombstone was excavated near Sase Monastery.

Middle Ages

An early Christian church dated to the 6th century was discovered in Srebrenica.[6]

In the 13th and 14th century the region was part of the Banate of Bosnia, and, subsequently, the Bosnian Kingdom. The earliest reference to the name Srebrenica was in 1376, by which time it was already an important centre for trade in the western Balkans, based especially on the silver mines of the region. (Compare modern srebro "silver".) By that time, a large number of merchants of the Republic of Ragusa were established there, and they controlled the domestic silver trade and the export by sea, almost entirely via the port of Ragusa (Dubrovnik).[7] During the 14th century, many German miners moved into the area.[8] There were often armed conflicts about Srebrenica because of its mines. According to Czech historian Konstantin Josef Jireček, from 1411 to 1463, Srebrenica switched hands several times, being Hungarian one time, Serbian five times, Bosnian four times, and Ottoman three times.[9] The mines of Bosnian Podrinje and Usora were part of the Serbian Despotate prior to the Ottoman conquest.[10]

Ottoman period

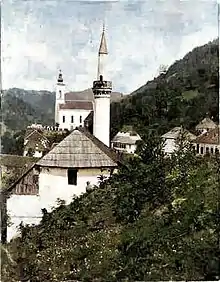

With the town coming under Ottoman rule, becoming less influenced by the Republic of Ragusa, the economic importance of Srebrenica went into decline, as did the proportion of Christians in the population. The Franciscan church of St. Nicholas was converted into the White Mosque, but the large number of Catholics, Ragusan and Saxon, caused the transformation of the town to Islam to be slower than in most of the other towns in the area.[11]

The area of Osat was liberated for a short time during the First Serbian Uprising (1804–13), under the leadership of Kara-Marko Vasić from Crvica. Upon the breakout of the uprising, Metropolitan Hadži Melentije Stevanović contacted Vasić, who met with the rebel leadership. After participating in battles on the Drina (1804), Vasić asked Karađorđe for an army to liberate Osat; Lazar Mutap was dispatched and the region came under rebel rule. In 1808, the Ottomans cleared out Osat, and by 1813, the rebels left the region.

Austro-Hungarian period

The town came under Austro-Hungarian rule in 1878, when the Congress of Berlin approved the occupation of the Bosnia Vilayet, which later in 1908 became a condominium under the joint control of Austria and Hungary. The natural mineral water springs Crni Guber ("Black Guber") developed into an important part of the local economy. The Bohemian company Mattoni established a distribution infrastructure to tap and export the water named Guber-Quelle ("Guber Spring") throughout the monarchy and abroad.[12] The construction of a spa was recommended.[13] Modern infrastructure such as administration, electricity, roads, schools, telephone, healthcare, a postal service and other things were introduced.[14]

Although the Austrian rulers tried to stop the spread of nationalism and favoured a multi-religious and multi-cultural makeup with religious tolerance under their hegemony, Serbian nationalism was viewed with suspicion and hostility, since it demanded a unification of Bosnia with Serbia. As modern education raised the levels of general literacy, ideas spread through the advent of newspapers and publications. The region became increasingly restless as nationalism spread to all groups.

During the First World War, one of the region's main battle areas was in Eastern Bosnia and the Drina, from where the units of Austria-Hungary advanced towards the Kingdom of Serbia. In late summer 1914 Srebrenica was taken over by Serbian volunteers under Kosta Todorović but later retaken by Austro-Hungarian units. Following World War I, Bosnia was incorporated into the South Slav kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which later was renamed Yugoslavia.

Second World War

During the Second World War there were many atrocities committed by the Chetniks and Ustashas. Partisans fought Chetniks and Ustashe during the war and the people of Srebrenica built a partisan memorial cemetery monument for the fallen victims.

Yugoslav period

Tourism gained importance during the communist Yugoslav period and wellness spa and taking to the waters became an important part of the local economy. The Banja Guber was constructed for that purpose. Up to the 1990s over 90,000 overnight stays were recorded and an annual income of about three million dollars generated.[15]

Bosnian War

The town of Srebrenica came to global prominence as a result of events during the Bosnian War (1992–1995). The strategic objectives proclaimed by the secessionist Bosnian Serb presidency included the creation of a border separating the Serb people from Bosnia's other ethnic communities and the abolition of the border along the River Drina separating Serbia and the Bosnian Serbs' Republika Srpska.[16] The Bosnian Muslim/Bosniak majority population of the Drina Valley posed a major obstacle to the achievement of these objectives. In the early days of the campaign of forcible transfer (ethnic cleansing) that followed the outbreak of war in April 1992 the town of Srebrenica was occupied by Serb/Serbian forces. It was subsequently retaken by Bosniak resistance groups. Refugees expelled from towns and villages across the central Drina valley sought shelter in Srebrenica, swelling the town's population.

The town and its surrounding area was surrounded and besieged by Serb forces. On 16 April 1993, the United Nations declared the Bosnian Muslim/Bosniak enclave a UN safe area, to be "free from any armed attack or any other hostile act", and guarded by a small Dutch unit operating under the mandate of United Nations Protection Force (UNPROFOR), which did not get permission to use force from the UN, which they needed to defend the local population.

Srebrenica and the other UN safe areas of Žepa and Goražde were isolated pockets of Bosnian government-held territory in eastern Bosnia. In July 1995, despite the town's UN-protected status, it was attacked and captured by the Army of Republika Srpska led by general Ratko Mladić. Following the town's capture, all men of fighting age who fell into Bosnian Serb hands were massacred in a systematically organised series of summary executions. The women of the town and men below 12 years of age and above 65 were transferred by bus to Tuzla. The Srebrenica massacre was the deadliest massacre in Europe since World War II,[17] being the only incident in Europe to have been recognized as a genocide since the Holocaust.[18]

In 2001, the Srebrenica massacre was determined by judgement of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) to have been a crime of genocide (confirmed on appeal in 2004).[19] This finding was upheld in 2007 by the International Court of Justice. The decision of the ICTY was followed by an admission to and an apology for the massacre by the Republika Srpska government.[20]

Under the 1995 Dayton Agreement which ended the Bosnian War, Srebrenica was included in the territory assigned to Bosnian Serb control as the Republika Srpska entity of Bosnia and Herzegovina. Although guaranteed under the provisions of the Dayton Agreement, the return of survivors was repeatedly obstructed. In 2007, verbal and physical attacks on returning refugees continued to be reported in the region around Srebrenica.[21]

Fate of Bosnian Muslim villages

In 1992, Bosniak villages around Srebrenica were under constant attacks by Serb forces. The Bosnian Institute in the United Kingdom has published a list of 296 villages destroyed by Serb forces around Srebrenica three years before the genocide and in the first three months of war (April–June 1992):[22]

More than three years before the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, Bosnian Serb nationalists – with the logistical, moral and financial support of Serbia and the Yugoslav People's Army (JNA) – destroyed 296 predominantly Bosniak (Bosnian Muslim) villages in the region around Srebrenica, forcibly uprooting some 70,000 Bosniaks from their homes and systematically massacring at least 3,166 Bosniaks (documented deaths) including many women, children and the elderly.

According to the Naser Orić trial judgement:[23]

"Between April 1992 and March 1993, Srebrenica town and the villages in the area held by Bosnian Muslims were constantly subjected to Serb military assaults, including artillery attacks, sniper fire, as well as occasional bombing from aircraft. Each onslaught followed a similar pattern. Serb soldiers and paramilitaries surrounded a Bosnian Muslim village or hamlet, called upon the population to surrender their weapons, and then began with indiscriminate shelling and shooting. In most cases, they then entered the village or hamlet, expelled or killed the population, who offered no significant resistance and destroyed their homes. During this period, Srebrenica was subjected to indiscriminate shelling from all directions on a daily basis. Potočari in particular was a daily target for Serb artillery and infantry because it was a sensitive point in the defence line around Srebrenica. Other Bosnian Muslim settlements were routinely attacked as well. All this resulted in a great number of refugees and casualties."

British Army documents declassified in 2019

The British National Archives in Kew released the documents dating back to July 1995 which deal with communication between British military and political actors during the Bosnian war. Several of the reports appear to blame the Bosniak Army (BiH) for provoking the Srebrenica attack. British intelligence doubted that Pale (Bosnian Serb headquarters) had any plans to overrun Srebrenica. Instead, the manoeuvre came as a response due to repeated Bosniak Army (BiH) attacks on BSA (Bosnian Serb Army) supply lines.

The recent BSA (Bosnian Serb Army) attack on Srebrenica enclave was prompted by constant BiH (Bosniak Army) attacks over the previous 3 months on BSA supply route to the south of the enclave. The BSA attacks are almost certainly initiated by the local commander and we don't think they are part of a Pale inspired plan to overrun the enclave.[24]

The BSA action is in direct response to BiH pressure on a BSA line of communication and the BSA reacted by forcing BiH back towards Srebrenica. The Serbs found that there was little resistance so they were able to exploit further than their original objective.[24]

When Serbs entered the town, General Mladić threatened to shell the Dutch camp if UN troops did not disarm Bosniak troops. However, the report confirms no Bosniak army soldiers remained at the camp, all 2,000 armed Muslims "had simply left during the night" in the direction of Tuzla.[24]

Post-war period

The town has a religious makeup of roughly half Muslim and half Orthodox. Most of the town's 23 mosques that were destroyed were reconstructed with donations and aid, also from abroad.[25][26]

Unemployment rates are high since the economy was destroyed and reconstruction progresses slowly, as in many parts of the country. There are plans to revive the mineral water and spa business again. The reconstruction of the Banja Guber was scheduled for 2019 but experienced delays.[27]

Politics

In 2007, Srebrenica's municipal assembly adopted a resolution demanding independence from the Republika Srpska entity (although not from Bosnia's sovereignty); the Serb members of the assembly did not vote on the resolution.[28] In the 2016 elections Mladen Grujičić, a Bosnian Serb and native of the town of Srebrenica, was elected as mayor.

The municipality emblem was developed during the Yugoslav period and depicts a red and white stylised "S" with a depiction of the mineral water spring in the lower middle and a tree in the upper middle. The spring underscores the historical importance to the town's economy and the tree the nature and forests of the region.

Local communities

The municipality (општина or opština) is further subdivided into the following local communities (мјесне заједнице or mjesne zajednice):[29]

- Brežani

- Crvica

- Donji Potočari

- Gornji Potočari

- Gostilj

- Kostolomci

- Brezova Njiva

- Krnići

- Luka

- Orahovica

- Osatica

- Podravanje

- Radoševići

- Ratkovići

- Sase

- Skelani

- Skenderovići

- Srebrenica

- Sućeska

- Toplica

- Viogor

Demographics

Population

| Settlement | 1953 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2013 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 24,712 | 29,283 | 33,357 | 36,292 | 36,666 | 13,409 | |

| 1 | Bostahovine | 495 | 272 | ||||

| 2 | Bučinovići | 386 | 215 | ||||

| 3 | Crvica | 473 | 484 | ||||

| 4 | Donji Potočari | 1,147 | 673 | ||||

| 5 | Gornji Potočari | 896 | 247 | ||||

| 6 | Gostilj | 148 | 461 | ||||

| 7 | Kalimanići | 397 | 366 | ||||

| 8 | Liješće | 524 | 213 | ||||

| 9 | Osmače | 948 | 251 | ||||

| 10 | Pećišta | 817 | 445 | ||||

| 11 | Petriča | 136 | 265 | ||||

| 12 | Skelani | 1,123 | 807 | ||||

| 13 | Srebrenica | 1,859 | 3,088 | 4,512 | 5,746 | 2,607 |

Ethnic composition

The borders of the municipality in the 1953 and 1961 census were different. In 1953, a distinctive Muslim nationality had been yet to emerge as an ethnicity, leading Slavic Muslims to identify as Yugoslavs. As Yugoslav was itself not adopted in 1948, they were classified as other and while many self-identified as “Serbs” or “Croats”.[30] Until 1961 census, the municipality of Srebrenica included today's territory of Bratunac municipality. The ethnic composition of the municipality:

| 2013 | 1991 | 1981 | 1971 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 2,607 (100,0%) | 5,746 (100,0%) | 4 512 (100,0%) | 3,088 (100,0%) |

| Bosniaks | 3,673 (63,92%) | 2,473 (54,81%) | 1,858 (60,17%) | |

| Serbs | 1,632 (28,40%) | 1,406 (31,16%) | 921 (29,83%) | |

| Yugoslavs | 328 (5,708%) | 496 (10,99%) | 89 (2,882%) | |

| Others | 79 (1,375%) | 15 (0,332%) | 64 (2,073%) | |

| Croats | 34 (0,592%) | 56 (1,241%) | 78 (2,526%) | |

| Montenegrins | 27 (0,598%) | 46 (1,490%) | ||

| Albanians | 22 (0,488%) | 17 (0,551%) | ||

| Slovenes | 6 (0,133%) | 6 (0,194%) | ||

| Roma | 6 (0,133%) | |||

| Macedonians | 5 (0,111%) | 4 (0,130%) | ||

| Hungarians | 5 (0,162%) |

| 2013 | 1991 | 1981 | 1971 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 13,409 (100,0%) | 36,666 (100,0%) | 36,292 (100,0%) | 33,357 (100,0%) |

| Bosniaks | 7,248 (54,05%) | 27,542 (75,12%) | 24,930 (68,69%) | 20,968 (62,86%) |

| Serbs | 6,028 (44,95%) | 8,315 (22,68%) | 10,294 (28,36%) | 11,918 (35,73%) |

| Others | 117 (0,873%) | 391 (1,066%) | 137 (0,377%) | 143 (0,429%) |

| Croats | 16 (0,119%) | 38 (0,104%) | 80 (0,220%) | 109 (0,327%) |

| Yugoslavs | 380 (1,036%) | 725 (1,998%) | 121 (0,363%) | |

| Montenegrins | 47 (0,130%) | 48 (0,144%) | ||

| Albanians | 39 (0,107%) | 26 (0,078%) | ||

| Roma | 21 (0,058%) | 5 (0,015%) | ||

| Slovenes | 11 (0,030%) | 6 (0,018%) | ||

| Macedonians | 8 (0,022%) | 8 (0,024%) | ||

| Hungarians | 5 (0,015%) |

| Settlement | Total | Bosniaks | Croats | Serbs | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bostahovine | 299 | 299 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Bučinovići | 221 | 221 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | Crvica | 551 | 0 | 1 | 549 | 1 |

| 4 | Donji Potočari | 673 | 363 | 1 | 330 | 11 |

| 5 | Gornji Potočari | 247 | 245 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 6 | Gostilj | 503 | 235 | 0 | 266 | 2 |

| 7 | Kalimanići | 377 | 14 | 0 | 363 | 0 |

| 8 | Liješće | 263 | 92 | 0 | 170 | 1 |

| 9 | Osmače | 264 | 264 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 10 | Pećišta | 550 | 356 | 1 | 190 | 0 |

| 11 | Petriča | 271 | 0 | 0 | 270 | 1 |

| 12 | Skelani | 824 | 217 | 0 | 605 | 2 |

| 13 | Srebrenica | 2,397 | 998 | 8 | 1,369 | 22 |

Culture

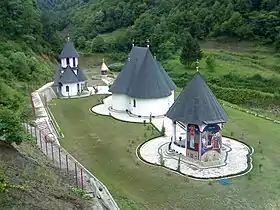

- Sase Monastery, Serbian Orthodox monastery dating back to 13th century

- White Mosque, dating to 17th century, on the foundations of a Franciscan Catholic church

- Čaršija mosque, built or rebuilt in 1836 by Selmanaga Selmanagic. Rebuilt in 1988, demolished in 1995, rebuilt in 2011 by Ahmed Smajlovic.[31]

- various other mosques such as the Red Mosque

- Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin (Srebrenica), dating to 1903[32]

- St Mary's Catholic Chapel[33]

- local museum[34]

- Mosque youth center (Omladinski centar), completed in 2019 in neo-Ottoman style[35]

- mineral water springs and spa

Economy

Before 1992, there was a metal factory in the town, and lead, zinc, and gold mines nearby. The town's name (Srebrenica) means "silver mine", the same meaning of its old Latin name Argentaria.

Before the war, Srebrenica also had a big spa and the town prospered from wellness tourism from the Crni Guber ("Black Guber") ferruginous spring water and other springs. Nowadays, Srebrenica has some tourism but a lot less developed than before the war. Currently, a pension, motel and a hostel are operating in the town.

- Economic preview

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[36]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 135 |

| Mining and quarrying | 537 |

| Manufacturing | 480 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 23 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 27 |

| Construction | 14 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 83 |

| Transportation and storage | 63 |

| Accommodation and food services | 26 |

| Information and communication | 8 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 9 |

| Real estate activities | - |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 20 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 10 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 232 |

| Education | 186 |

| Human health and social work activities | 104 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 28 |

| Other service activities | 28 |

| Total | 2,013 |

Notable people

- Selman Selmanagić (b. 1905), Bosnian-German architect from the Bauhaus school[37]

- Milorad Simić (b. 1946), philologist

- Desnica Radivojević (born 1952), Bosnian politician

- Sabahudin Vugdalić (born 1953), Bosnian sports journalist and former football goalkeeper

- Naser Orić (b. 1967), Bosnian military officer during Bosnian war 1992–1995

- Emir Suljagić (b. 1975), author

- Hamza Alić (b. 1979), shot putter

- Muamer Jahić (born 1979), Bosnian footballer

- Mladen Grujičić (born 1982), Bosnian Serb politician and mayor of Srebrenica

- Sanin Muminović (born 1990), Croatian footballer

- Esmir Ahmetović (born 1991), Bosnian footballer

- Mirsad Bektić (b. 1991), Bosnian-American UFC fighter

- Asmir Suljić (b. 1991), footballer

- Mirzad Mehanović (born 1993), Bosnian footballer

- Kadir Hodžić (born 1994), Bosnian footballer

- Emir Sulejmanović (b. 1995), basketball player

References

- ↑ Hajdarbegovic, Emir. "Istorijat Srebrenice". www.srebrenica.gov.ba. Archived from the original on 2020-10-31. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ↑ W. Carter 1977, p. 411.

- ↑ "Сребреница кроз историју | Туристичка организација Републике Српске" (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 2022-07-06. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

- ↑ "Remembering Srebrenica – a town that once prospered from its metal industry and spa tourism, before the war came". This City Knows. 2017-07-11. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ↑ "Srebrenica". The Forum for Cities in Transition. 2014-08-19. Archived from the original on 2021-06-24. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- ↑ Srpska, RTRS, Radio Televizija Republike Srpske, Radio Television of Republic of. "Srebrenica: Ostaci crkve iz šestog vijeka za vjerske obrede, nastavu i turiste (FOTO)". DRUŠTVO - RTRS. Archived from the original on 2021-03-07. Retrieved 2021-03-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Konstantin Jireček: Die Handelsstrassen und Bergwerke von Serbien und Bosnien während des Mittelalters: historisch-geographische Studien. Prag: Verl. der Kön. Böhmischen Ges. der Wiss., 1879

- ↑ Mihailo Dinić: Za istoriju rudarstva u srednjevekovnoj Srbiji i Bosni, S. 46

- ↑ Jireček 1952, p. 403.

- ↑ Salih Kulenović (1995). Etnologija sjeveroistočne Bosne: rasprave, studije, članci. Muzej istočne Bosne. p. 20. Archived from the original on 2023-03-24. Retrieved 2016-01-01.

- ↑ A Short History of Bosnia, S. 53 ff.

- ↑ "Guber voda: Kako je sve počelo i gdje smo sada". Archived from the original on 2017-05-22. Retrieved 2020-07-11.

- ↑ Durch Bosnien und die Hercegovina kreuz und quer, p. 186, at Google Books

- ↑ Durch Bosnien und die Hercegovina kreuz und quer, p. 187, at Google Books

- ↑ "Banja Guber – nada bolesnicima i Srebreničanima | DW | 24.11.2013". Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 2020-07-12. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- ↑ "Tolimir et al. CASE NO. IT-04-80-I". Archived from the original on 2016-03-12. Retrieved 2010-08-26.

- ↑ "Srebrenica reburies 308 victims of massacre". NBC News. 11 July 2008. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "'It's getting out of hand': genocide denial outlawed in Bosnia". The Guardian. 24 July 2021. Archived from the original on 24 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ↑ "Krstic – Judgement". International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. 19 April 2004. Archived from the original on 10 July 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "Serbs sorry for Srebrenica deaths". BBC. 10 November 2004. Archived from the original on 4 September 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2009.

- ↑ "7th Session of the UN Human Rights Council" (PDF). Society for Threatened Peoples. 21 February 2008. p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- ↑ Bosnian Institute UK, the 26-page study: "Prelude to the Srebrenica Genocide – mass murder and ethnic cleansing of Bosniaks in the Srebrenica region during the first three months of the Bosnian War (April–June 1992) Archived 2013-09-06 at the Wayback Machine", 18 November 2010.

- ↑ "Naser Oric Trial Judgement, ICTY" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-06-06. Retrieved 2009-10-10.

- 1 2 3 "YUGOSLAVIA. Internal situation: UK/Yugoslavia relations; part 46". The National Archives. The National Archives, Kew. Archived from the original on 29 February 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- ↑ "Obnova džamija u Srebrenici: Nakon rušenja 23 bogomolje, 19 ih je obnovljeno | Faktor.ba". www.faktor.ba. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "U Srebrenici svečano otvorena Đozića džamija | BNN". bnn.ba. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2022.

- ↑ "Banja Guber ne počinje sa radom ove godine". 10 December 2019. Archived from the original on 14 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ↑ "Srebrenica pushes for partition". B92. 25 March 2007. Archived from the original on 4 June 2012. Retrieved 29 March 2007.

- ↑ Archived April 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Malcolm, Noel (1996). Bosnia: A Short History. New York, NY: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0814755617.

- ↑ "Remains of Carsija Mosque in Srebrenica found, mined and demolished in 1995 – Sarajevo Times". 8 February 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-07-17. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- ↑ https://www.esrebrenica.ba/upoznaj-srebrenicu/pocela-rekonstrukcija-srebrenicke-gradske-crkve.html

- ↑ "Religijsko bogatstvo - Kapela Svete Marije u Srebrenici". Archived from the original on 2016-09-10. Retrieved 2020-07-17.

- ↑ "Muzej Srebrenica – Turisticka organizacija Srebrenice". Archived from the original on 2020-07-14. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- ↑ "Vijesti". 26 April 2018. Archived from the original on 2020-07-12. Retrieved 2020-07-12.

- ↑ "Cities and Municipalities of Republika Srpska" (PDF). rzs.rs.ba. Republika Srspka Institute of Statistics. 25 December 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ↑ "Selman Selmanagić: The Architect from Srebrenica". Archived from the original on 2021-01-31. Retrieved 2021-01-27.

Sources

- Bideleux & Jeffries, Robert and Ian (2007). The Balkans: A Post-Communist History. Routledge. ISBN 9780203969113. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- Ćorović, Vladimir (1989). Istorija Srba. Beogradski izdavačko-grafički zavod. ISBN 978-86-13-00381-6.

- W. Carter, Francis (1977). An Historical Geography of the Balkans. Academic Press. p. 411. ISBN 978-0-12-161750-9.

- Jireček, Konstantin (1952). Istorija Srba. Belgrade: Naučna knjiga.

External links

- Opština Srebrenica – Srebrenica municipality (in Bosnian)

- The Advocacy Project partners with Bosnian Family (BOSFAM)

- Fiction stories about Srebrenica women: Integration Under the Midnight Sun Archived 2014-10-06 at the Wayback Machine by Adnan Mahmutovic