St. Charles, Missouri | |

|---|---|

Historic Main Street | |

Flag | |

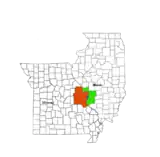

Location in the state of Missouri | |

| Coordinates: 38°47′20″N 90°30′50″W / 38.789°N 90.514°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Missouri |

| County | Saint Charles |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Dan Borgmeyer |

| Area | |

| • Total | 25.67 sq mi (66.48 km2) |

| • Land | 25.17 sq mi (65.19 km2) |

| • Water | 0.50 sq mi (1.29 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Total | 70,493 |

| • Density | 2,800.79/sq mi (1,081.40/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 63301-63304 |

| Area codes | 636, 314 |

| FIPS code | 29-64082 |

| Website | www.stcharlescitymo.gov |

Saint Charles (commonly abbreviated St. Charles) is a city in, and the county seat of, St. Charles County, Missouri, United States.[2] The population was 70,493 at the 2020 census, making St. Charles the 9th most populous city in Missouri. Situated on the Missouri River, St. Charles is a northwestern suburb of St. Louis.

The city was founded circa 1769 as Les Petites Côtes, or "The Little Hills" in French, by Louis Blanchette, a French-Canadian fur trader.[3] This former French area west of the Mississippi River was nominally ruled by Spain following France's defeat in the Seven Years' War. France had ceded its eastern territories to Great Britain. St. Charles is the third-oldest city in Missouri. For a time, it played a significant role as a river port in the United States' westward expansion, including trade with Native American tribes on the upper Missouri River. It was the starting point of the Boone's Lick Road to the Boonslick.

St. Charles was settled primarily by French-speaking colonists from Canada in its early days. In 1804 the Lewis and Clark Expedition considered this settlement the last "civilized" stop before they headed upriver to explore the western territory that the United States acquired from France in the Louisiana Purchase.[4]

The city served as the first Missouri capital from 1821 to 1826.[5] It is the site of the Saint Rose Philippine Duchesne shrine.[6]

History

Native American peoples inhabited the area at least as early as 11,000 B.C. When European colonists arrived, the area was inhabited by the historic Ilini, Osage and Missouri tribes.

According to Hopewell's Legends of the Missouri and Mississippi, Blanchette met another French Canadian (Bernard Guillet) at this site in 1765. Blanchette, determined to settle there, asked if Guillet, who had become an honorary chief of a Dakota band, had chosen a name for it.

- "I called the place 'Les Petites Côtes' " replied Bernard, "from the sides of the hills that you see."

- "By that name shall it be called", said Blanchette Chasseur, "for it is the echo of nature—beautiful from its simplicity."

Blanchette settled there circa 1769 under the authority of the Spanish governor of Upper Louisiana (the area had been ceded by France to Spain under an agreement with Great Britain following French defeat in the French and Indian Wars). He was appointed as the territory's civil and military leader, serving until his death in 1793. Although the settlement was under Spanish jurisdiction, the settlers were primarily Native American and French Canadians who had migrated from northern territories. Most settlers spoke French.

Considered to begin in St. Charles, the Boone's Lick Road along the Missouri River was the major overland route for European-American settlement of central and western Missouri. This area became known as the Boonslick or "Boonslick Country." At Franklin, the trail ended. Westward progress continued on the Santa Fe Trail.

San Carlos Borromeo

The first church, built in 1791, was Catholic and dedicated to the Italian saint Charles Borromeo, under the Spanish version of his name, San Carlos Borromeo. The town became known as San Carlos del Misuri (St. Charles of the Missouri). The original location of the church is not known but a replica has been built just off Main Street. The fourth St. Charles Borromeo Church now stands on Fifth Street.

The Spanish Lieutenant-Governor Carlos de Hault de Lassus appointed Daniel Boone as commandant of the Femme Osage District. He served in this role until the United States government acquired control in 1804 following the Louisiana Purchase from France.

The name of the town, San Carlos, was anglicized to St. Charles. William Clark arrived in St. Charles on May 16, 1804. With him were 40 men and three boats; they made final preparations for their major cross-country expedition, as they waited for Meriwether Lewis to arrive from St. Louis. They attended dances, dinners, and a church service during this time. Excited to be part of the national expedition, the townspeople were very hospitable to the explorers. Lewis arrived via St. Charles Rock Road on May 20. The expedition launched the next day in a keel boat at 3:30 pm. St. Charles was the last established European-American town that the expedition visited for more than two and a half years.

State capital and growth

When Missouri was granted statehood in 1821, the legislature decided to build a "City of Jefferson" to serve as the state capital, in the center of the state, overlooking the Missouri River. Since this land was undeveloped at the time, a temporary capital was needed. St. Charles was chosen over eight other cities in a competition to house the temporary capital. It offered free meeting space for the legislature in rooms located above a hardware store. This building is preserved as the First Missouri State Capitol State Historic Site and may be toured. The Missouri government continued to meet there until buildings were completed in Jefferson City in 1826.

Gottfried Duden was a German who visited in the area in 1824. Travelling under the guidance of Daniel M. Boone, he wrote extensive accounts of life in St. Charles County during his year there. He published these after returning to Germany in 1829, and his favorable impressions of the area led to the immigration of a number of Germans in 1833. The first permanent German settler in the region was probably Louis Eversman, who had arrived with Duden but decided to stay.

In the post-World War II era, the federal government undertook a major program of interstate highway construction. St. Charles is where the first claimed interstate project was started in 1956. A state highway marker is displayed with a logo and information regarding this claim, off Interstate 70 going westbound, to the right of the First Capitol Drive exit. Kansas and Pennsylvania also claim to have had the first interstate project.[7]

Geography

St. Charles is located about 20 miles northwest of St. Louis. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 24.03 square miles (62.24 km2), of which 23.65 square miles (61.25 km2) is land and 0.38 square miles (0.98 km2) is water.[8]

Climate

St. Charles has a Köppen humid subtropical climate, with warm and humid summers (eventual hot days) and cool winters (with short cold spells possible sometimes). Precipitation is mostly light to moderate, with occasional stormy weather. Spring is the wettest season on average.

| Climate data for St Charles, Missouri (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1893–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 82 (28) |

83 (28) |

93 (34) |

94 (34) |

101 (38) |

106 (41) |

115 (46) |

112 (44) |

106 (41) |

97 (36) |

87 (31) |

77 (25) |

115 (46) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.5 (4.2) |

44.7 (7.1) |

55.2 (12.9) |

66.8 (19.3) |

76.0 (24.4) |

84.1 (28.9) |

88.0 (31.1) |

86.8 (30.4) |

80.4 (26.9) |

68.8 (20.4) |

55.3 (12.9) |

44.1 (6.7) |

65.8 (18.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 30.7 (−0.7) |

35.0 (1.7) |

44.4 (6.9) |

55.4 (13.0) |

65.5 (18.6) |

74.2 (23.4) |

78.2 (25.7) |

76.3 (24.6) |

68.8 (20.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

45.3 (7.4) |

35.2 (1.8) |

55.5 (13.1) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 21.9 (−5.6) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

33.7 (0.9) |

44.0 (6.7) |

55.1 (12.8) |

64.3 (17.9) |

68.3 (20.2) |

65.8 (18.8) |

57.2 (14.0) |

45.7 (7.6) |

35.3 (1.8) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

45.2 (7.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−24 (−31) |

−7 (−22) |

0 (−18) |

30 (−1) |

41 (5) |

47 (8) |

43 (6) |

31 (−1) |

19 (−7) |

−4 (−20) |

−19 (−28) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.74 (70) |

2.86 (73) |

3.63 (92) |

5.11 (130) |

5.45 (138) |

4.35 (110) |

4.20 (107) |

4.07 (103) |

3.08 (78) |

3.50 (89) |

3.73 (95) |

2.99 (76) |

45.71 (1,161) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.3 (11) |

2.6 (6.6) |

0.5 (1.3) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.5 (3.8) |

9.0 (23) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 7.5 | 6.9 | 9.7 | 10.3 | 11.4 | 9.1 | 8.4 | 7.3 | 7.0 | 8.2 | 8.1 | 7.1 | 101.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 2.1 | 1.8 | 0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.4 | 1.0 | 5.6 |

| Source: NOAA[9][10] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1850 | 1,498 | — | |

| 1860 | 3,239 | 116.2% | |

| 1870 | 5,570 | 72.0% | |

| 1880 | 5,014 | −10.0% | |

| 1890 | 6,161 | 22.9% | |

| 1900 | 7,982 | 29.6% | |

| 1910 | 9,437 | 18.2% | |

| 1920 | 8,503 | −9.9% | |

| 1930 | 10,491 | 23.4% | |

| 1940 | 10,803 | 3.0% | |

| 1950 | 14,314 | 32.5% | |

| 1960 | 21,189 | 48.0% | |

| 1970 | 31,834 | 50.2% | |

| 1980 | 37,379 | 17.4% | |

| 1990 | 54,555 | 46.0% | |

| 2000 | 60,321 | 10.6% | |

| 2010 | 65,794 | 9.1% | |

| 2020 | 70,493 | 7.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[11] | |||

2020 census

The 2020 United States census[12] counted 70,493 people, 29,051 households, and 16,791 families in St. Charles. The population density was 2,800.7 per square mile (1,081.3/km2). There were 30,986 housing units at an average density of 1,231.1 per square mile (475.3/km2). The racial makeup was 79.23% (55,850) white, 7.75% (5,460) black or African-American, 0.25% (175) Native American or Alaska Native, 3.28% (2,315) Asian, 0.06% (40) Pacific Islander, 2.73% (1,925) from other races, and 6.71% (4,728) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race was 5.7% (4,016) of the population.

Of the 29,051 households, 21.7% had children under the age of 18; 46.4% were married couples living together; 26.0% had a female householder with no husband present. Of all households, 33.5% consisted of individuals and 12.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.2 and the average family size was 2.9.

17.3% of the population was under the age of 18, 13.6% from 18 to 24, 27.6% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 17.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37.6 years. For every 100 females, the population had 91.9 males. For every 100 females ages 18 and older, there were 90.7 males.

The 2016-2020 5-year American Community Survey[13] estimates show that the median household income was $71,232 (with a margin of error of +/- $3,225) and the median family income was $90,211 (+/- $3,208). Males had a median income of $46,607 (+/- $2,598) versus $28,573 (+/- $5,404) for females. The median income for those above 16 years old was $37,734 (+/- $3,118). Approximately, 5.0% of families and 7.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 9.6% of those under the age of 18 and 4.6% of those ages 65 or over.

2010 census

As of the census[14] of 2010, there were 65,794 people, 26,715 households, and 16,128 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,782.0 inhabitants per square mile (1,074.1/km2). There were 28,590 housing units at an average density of 1,208.9 per square mile (466.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 87.5% White, 5.9% African American, 0.3% Native American, 2.5% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.8% from other races, and 1.9% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.2% of the population.

There were 26,715 households, of which 27.5% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 45.4% were married couples living together, 10.8% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.2% had a male householder with no wife present, and 39.6% were non-families. 31.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 10.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.29 and the average family size was 2.90.

The median age in the city was 36.6 years. 19.7% of residents were under the age of 18; 13.8% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 25.9% were from 25 to 44; 26.6% were from 45 to 64; and 13.9% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 49.0% male and 51.0% female.

According to 2014, American Community Survey 5-year Estimates the median income for a household in the city was $56,622, and the median income for a family was $73,234. Males had a median income of $51,477 versus $40,311 females. The per capita income for the city was $29,645. 8.8% of families and 11.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 18.7% of those under age 18 and 6.0% of those age 65 or over.

2000 census

As of the census[15] of 2000, there were 60,321 people, 24,210 households, and 15,324 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,962.4 inhabitants per square mile (1,143.8/km2). There were 25,283 housing units at an average density of 1,241.6 per square mile (479.4/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.28% White, 3.48% African American, 0.27% Native American, 1.01% Asian, 0.04% Pacific Islander, 0.73% from other races, and 1.19% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.97% of the population.

There were 24,210 households, out of which 30.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 49.4% were married couples living together, 10.2% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.7% were non-families. 29.6% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.1% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.38 and the average family size was 2.98.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 23.4% under the age of 18, 12.0% from 18 to 24, 30.5% from 25 to 44, 22.0% from 45 to 64, and 12.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females, there were 96.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $47,782, and the median income for a family was $60,175. Males had a median income of $40,827 versus $27,778 for females. The per capita income for the city was $23,607. About 4.6% of families and 6.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.1% of those under age 18 and 5.9% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

According to the city's 2015 Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,[16] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | # of Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ameristar Casinos | 1,620 |

| 2 | St. Charles County | 1,500 |

| 3 | SSM St. Joseph Health Center | 1,352 |

| 4 | Boeing | 1,170 |

| 5 | City of St. Charles School District | 852 |

| 6 | Client Services Inc. | 698 |

| 7 | Lindenwood University | 618 |

| 8 | AT&T Missouri | 600 |

| 9 | Central States Coca-Cola | 500 |

| 10 | City of St. Charles | 494 |

Pharma Medica, a contract research and biotechnology corporation, opened its first U.S. location in 2013 in St. Charles. It began conducting clinical trials in February 2014. Its goal was to create 320 high tech jobs by early 2017.

Culture

St. Charles lies near the eastern end of the Katy Trail, a 225-mile (362 km) long state park that was adapted from railroad right-of-way. Since the late 1970s, there has been rapid new home construction, commercial and population growth in the St. Charles area. The phrase "Golden Triangle" was coined by developers of this area in the 1980s, referring to the St. Charles County region bordered by highways Interstate 70, Interstate 64, and Route 94.

St. Charles has a historic shopping district on Main Street. Numerous restored buildings house such tourist destinations as restaurants and various specialty stores. Since 2015, walking food tours on Historic Main Street can be taken through the company Dishing Up America. These tours take customers to the locally famous restaurants in the city.

The city has many special events and features related to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. In 2007, St. Charles welcomed men's professional road bicycle racing riders and fans, as it served as the stage 5 final for the 2007 Tour of Missouri.

While it does not offer a public golf course, the St. Charles Parks and Recreation System opened a dog park on the north side of the city as a part of DuSable Park-Bales Area in November 2006. This off-leash dog area has two sections – one for smaller dogs, one for larger.

The St. Charles Convention Center brings visitors, meetings and events to the city. The Family Arena, a county-owned 11,000-seat venue, was built in 1999 near the Missouri River. It is used by minor league sports franchises and hosts concerts and events.

Riverfront

The Riverfront and Main Street area in the St. Charles Historic District is a central gathering place and focal point for the community. The primary features of the riverfront and Historic Main Street are residences and businesses. Each block features shops, restaurants, and offices frequented by visitors and locals. Much is planned for the development and improvement of the area, including a northward extension of the Katy Trail, residential and commercial development, parking garage expansion, casino expansion, and development of hotels.

The Christmas Traditions Festival, one of the nation's larger Christmas festivals, takes place on the streets of St. Charles annually. It starts the day after Thanksgiving and continues until the Saturday after Christmas. Over 30 costumed Legends of Christmas stroll the streets and interact with guests, and Victorian Era Christmas Carolers fill the air with old-fashioned carols. Every Saturday and Sunday, the Legends of Christmas and the Lewis & Clark Fife and Drum Corps take part in the Santa Parade as it heads up Historic South Main Street to the site of the First Missouri State Capitol.

On the Fourth of July fireworks displays draw large numbers on two nights, July 4 and another night before or after the Fourth. Many bring blankets to sit near the riverfront. Others opt to view the festivities from the Old Courthouse. The festival, named Riverfest, has been sponsored by the city of St. Charles and organized by a volunteer committee formed of city residents and sponsoring private organization (like the Jaycees) leaders.

The Festival of the Little Hills is a historic St. Charles tradition that takes place every year in August, the third full weekend of the month. Started in 1971, this festival is known nationally as one of the top ten craft fairs.[17] It runs through an entire weekend featuring great food, live entertainment, craft sales, and shows for kids. The festival is related to the famous Lewis & Clark expedition: many participants don clothing from the era and re-enact historic events. The city also encourages individuals to bring homemade crafts, jewelry, paintings, clothing and other items to sell at the festival.

Oktoberfest, held near the river, celebrates the historic German influence on the city. Many vendors sell beer and other German goods. It includes a parade. Missouri Tartan Day is a celebration of Scottish American heritage and culture held each spring, coinciding as closely as possible with April 6. This is the anniversary of the signing of the Declaration of Arbroath in 1320. The event features a parade with marching bagpipers from around the world and region, Scottish heavy athletics (caber toss, hammer throw, etc.), musical entertainment, traditional and contemporary foods. Highlights include the Kirkin' o' the Tartans (ceremony of blessing for the Scottish clans), displays of traditional Scottish clan tartans, and demonstrations of traditional Scottish activities and games.

The Fete de Glace is an ice-carving competition and demonstration held on North Main Street in mid-January. The Missouri River Irish Festival is held every September in Frontier Park and on Main Street to celebrate Irish Heritage with music, dancing, storytelling, athletics, food, and fun.[18] During Quilts on Main Street, hundreds of quilts are displayed outside the shops on storefronts and balconies. This event is held annually in September. The Bluegrass Festival in Frontier Park on the big stage of Jaycee's pavilion is held early in September every year, featuring local and regional acts. The MOSAICS Fine Art Festival is also held on Historic Main Street each September to showcase local, regional and national artists. LGBTQ+ organization Pride St. Charles holds an annual pride festival yearly in June, formerly at Blanchette Park and most recently at the St. Charles Family Arena.

Sports

The city has been home to several minor league sports teams. The Missouri River Otters hockey team of the United Hockey League, played from 1999 until the team folded in 2006. The River Otters played at the 11,000-seat Family Arena.[19] The St. Louis Ambush is a professional indoor soccer team that plays in the Family Arena. The RiverCity Rage professional indoor football team played in St. Charles from 2001 until 2005, and from 2007 to 2009 before suspending operations for 2010. Since 2014 there is a new minor league soccer team in town, the St. Louis Ambush at the Family Arena.[20][21]

| Team | Sport | League | Established | Venue | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St. Louis Ambush | Indoor soccer | MISL/PASL/MASL | 2013 | Family Arena | |

| St. Louis Vipers | Roller hockey | National Roller Hockey League | 2019 | Family Arena | |

Government

St. Charles is a charter city under the Missouri Constitution, with a City Council as the governing body. One member is elected for each of the ten wards, in an arrangement known as single-member districts, and each serves a three-year term.[22]

The executive head of the city government is the mayor for all legal and ceremonial purposes. Elected at-large for a four-year term, the mayor appoints the members of the various boards, commissions, and committees created by ordinance. The current mayor is Dan Borgmeyer; he was sworn into office on May 7, 2019.[23]

| Ward | City Council Member[24] |

|---|---|

| 1 | Christopher Kyle |

| 2 | Tom Besselman |

| 3 | Vince Ratchford |

| 4 | Mary West |

| 5 | Denise Mitchell |

| 6 | Jerry Reese |

| 7 | Michael Flandermeyer |

| 8 | Michael Galba |

| 9 | Bart Haberstroh |

| 10 | Bridget Ohmes |

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dan Borgmeyer | 4,455 | 55.33% | |

| Sally Faith | 3,570 | 44.34% | |

| Write-in | 27 | 0.34% | |

Education

The City of St. Charles School District has six elementary schools, two middle schools, two high schools, and the Lewis & Clark Career Center located at 2400 Zumbehl Road. St. Charles High School (sometimes called SCHS or simply "High") was the first built (1895) of the two high schools. It first operated as a private military academy for boys.

In the 1950s, it was acquired by the city and adapted as a public high school. St. Charles West (SCW or simply West) was constructed in the late 1970s in response to the city's growing population. St. Charles West had its first graduation in 1979. St. Charles High School underwent renovation in 1995 to improve both the exterior and interior of the building. St. Charles West was renovated in 2005, and a new library and auxiliary gym were built. The city is also served by Jefferson Intermediate, which has all 5th and 6th grade classes, and Hardin Middle School, which has all 7th and 8th grade classes.

A variety of private schools also operate here, each affiliated with a religious denomination. These include Immanuel Lutheran (Pre-K to 8), Zion Lutheran (Pre-K to 8), St. Charles Borromeo, St. Peter's, St. Cletus (K–8), Academy of the Sacred Heart (founded by Saint Rose Philippine Duchesne, and the site of her shrine), Duchesne High School (formerly named St. Peter High school), and St. Elizabeth Ann Seton-St. Robert Bellarmine (K–8).

Other schools are associated with the Francis Howell and the Orchard Farm school districts, which also serve parts of St. Charles. Many students who live on the southern edge of St. Charles City attend Henderson, Becky David, or Harvest Ridge elementary schools, Barnwell Middle, and Francis Howell North High School. To the North, the Orchard Farm School District also serves St. Charles. Like the Francis Howell School District, it is based outside the city limits, and has two elementary schools, a middle school, and a high school.

Lindenwood University is located on Kingshighway, near downtown St. Charles and St. Charles High. Founded by Major George Sibley and his wife Mary in 1827 as a women's school named Lindenwood School for Girls, the institution is the second-oldest higher-education institution west of the Mississippi River.[26] The private university is affiliated with the Presbyterian Church.

In the 21st century, LU is one of the fastest-growing universities in the Midwest. It enrolls close to 15,000 students. In 2006, it briefly attracted publicity when People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals staged a small protest against its unusual tuition fee policies: In an effort to help rural students pay for higher education, LU allowed families to sell livestock to the school. The animals were slaughtered and processed for serving at campus dining halls.[27] Lindenwood hosts 89.1 The Wood (KCLC), a commercial-free student-driven radio station.

St. Charles was also home to the now defunct St. Charles College (which should not be confused with St. Charles Community College),[28] and Vatterott College.[29]

Transportation

| Proposed St. Charles City Streetcar | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overview | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | St. Charles, Missouri | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 5 (proposed) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Streetcar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | St. Charles Area Transit | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 10-mile (16 km) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

According to the FHA, St. Charles was the site of the first interstate highway project in the nation.[30] Major highways include Interstates 64 and 70, Missouri 370, Missouri 94, and Missouri 364. Also see: St. Charles Area Transit

The "St. Charles City Streetcar" was a proposed new heritage streetcar line to be built connecting the New Town, Missouri residential development to the heart of the city of St. Charles.[31] This is a joint effort between Whittaker Builders, Inc, and the City of St. Charles and St. Charles Area Transit.[32] A minimum of nine vintage PCC streetcars (not to be confused with cable cars), had been purchased from the San Francisco area by Whittaker Builders for use and spare parts.[32] The project stalled, and in 2012, the streetcars purchased by Whittaker Builders were scrapped following a fire. Whittaker, a developer of the New Town project and principal partner with the city on the streetcar project, has since gone bankrupt,[33] ending the proposed street car line.

Notable people

- Cody Asche, professional baseball third baseman and outfielder

- Brandon Bollig, ice hockey player

- Daniel Boone, lived in St. Charles around 1809 to be near his grandson in boarding school.[34]

- Lou Brock, St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Famer

- Mark Buehrle, pitcher for 2005 World Series champion Chicago White Sox

- Rose Philippine Duchesne, Catholic saint and founder of Sacred Heart Academy

- R. Budd Dwyer, Pennsylvania State Treasurer who committed suicide during a live press conference in 1987

- Josh Harrellson, basketball player

- Tim Hawkins, comedian

- Mike Henneman, former pitcher for the Detroit Tigers

- Randy Orton, professional wrestler in WWE

- Tyson Pearce, professional soccer player who plays for St. Louis City SC in the Major League Soccer league

- Jim Pendleton, Milwaukee Braves outfielder

- Mathew Pitsch, Republican former member of the Arkansas Senate and House of Representatives; former resident of St. Charles[35]

- Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, founder of Chicago

- Tim Ream, soccer player, New York Red Bulls and U.S. National Team defender

- Ken Reitz, former third baseman for the St. Louis Cardinals (1972–75)

- Santino Rice, fashion designer and TV personality

- Patrick Schulte, professional soccer who plays for Columbus Crew in the Major League Soccer league

- Jeanne Shaheen, United States Senator from New Hampshire

- Nathaniel Simonds, State Treasurer of Missouri

- Jacob Turner, professional baseball pitcher

In popular culture

The scenes in St. Charles in Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 were filmed in Cartersville, Georgia.[36]

Star-Lord from Guardians of the Galaxy is from St. Charles.[37]

Sister cities

– Ludwigsburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany since 1996

– Ludwigsburg, Baden-Württemberg, Germany since 1996 – Carndonagh, County Donegal, Ireland since 2012

– Carndonagh, County Donegal, Ireland since 2012 – Inishowen, Ireland since 2018

– Inishowen, Ireland since 2018

References

- ↑ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Historic Saint Charles". Greatriverroad.com. Archived from the original on August 6, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Timeline". Stcharlescitymo.gov. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ↑ "St. Charles: Missouri's First Capitol". Slfp.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ↑ Shrine of St. Philippine Duchesne Archived 2011-07-25 at the Wayback Machine, Academy of the Sacred Heart. Retrieved 2009-10-15.

- ↑ Weingroff, Richard F. (Summer 1996). "Three States Claim First Interstate Highway". Public Roads. Vol. 60, no. 1. Retrieved April 26, 2023 – via Federal Highway Administration.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ↑ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Station: St Charles Elm PT, MO". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 24, 2021.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 8, 2012.

- ↑ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "City of St. Charles Comprehensive Annual Financial Report". stcharlescitymo.gov. Archived from the original on February 28, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ↑ "Festival of the Little Hills – Fête des Petites Côtes, Historic St. Charles, Missouri". www.festivalofthelittlehills.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2018.

- ↑ Missouri River Irish Fest Archived 2014-01-09 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Missouri River Otters of the UHL at". Hockeydb.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2012. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ↑ [stlouisambush.com]

- ↑ "Owner shuts down IFL's River City". Billingsgazette.com. October 17, 2009. Archived from the original on August 4, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ↑ "City Council". Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ↑ "Mayor | St. Charles, MO". Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ↑ "City Council – St. Charles, MO – Official Website". Archived from the original on December 16, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ↑ "Election Night Results".

- ↑ "Abbeville Institute 2008 Lindenwood Summer School". Abbevilleinstitute.org. Archived from the original on April 14, 2010. Retrieved July 11, 2010.

- ↑ "Dennis Spellmann, 70, President who Remade Struggling College, Dies." New York Times 3 September 2006. Nytimes.com. 25 January 2007 (link) Archived 2008-04-22 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "article mentioning St. Charles College". Libraryindex.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Vatterott College – St. Charles Missouri". Archived from the original on March 28, 2015. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ "First interstate project". Fhwa.dot.gov. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ↑ "New Town Saint Charles". DPZ Partners LLC. 2016. Archived from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- 1 2 Kaatmann, Rachel (June 6, 2007). "Trolley cars arrive". St. Louis Post Dispatch. Archived from the original on April 13, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ↑ "Lost Streetcars of San Francisco, Now Lost in Missouri". San Francisco Market Street Railway. March 31, 2010. Archived from the original on February 28, 2019. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ↑ Robert Morgan, Boone: A Biography, Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 2008, pp. 419-420

- ↑ "Mathew W. Pitsch". intelius.com. Archived from the original on April 8, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2015.

- ↑ Peters, Megan (April 14, 2017). "Guardians Of The Galaxy Vol. 2 Clip Sheds Light On Film's Earthbound Scenes". ComicBook.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ↑ "'Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2' has deep Missouri roots". The Kansas City Star Newspaper. The Kansas City Star. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

External links

- St. Charles City

- Greater St. Charles Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Greater St. Charles County Chamber of Commerce

- Historic maps of St. Charles in the Sanborn Maps of Missouri Collection at the University of Missouri