St. Michaels Historic District | |

| |

| |

| Location | Saint Michaels, Maryland |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°47′4″N 76°13′24″W / 38.78444°N 76.22333°W |

| Area | 105 acres (42 ha) |

| Built | 1778 |

| Architectural style | Italianate, Gothic Revival, Federal |

| NRHP reference No. | 86002427 |

| Added to NRHP | September 11, 1986 |

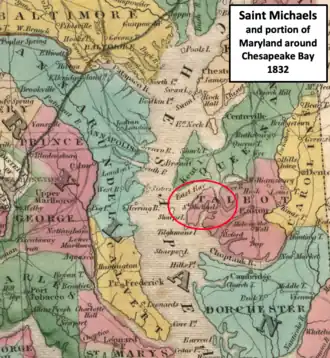

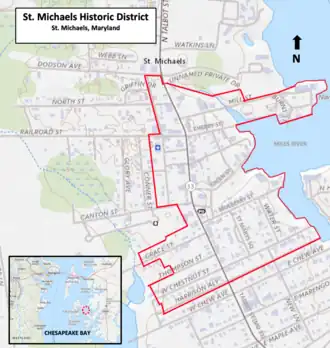

The Saint Michaels Historic District encompasses the historic center of Saint Michaels, Maryland. The town, which has about 1,000 permanent residents, is located on a tributary to the Chesapeake Bay on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. After over 100 years as a center for trade and shipbuilding, the community was incorporated as a town in 1805. Shipbuilding peaked in 1820, and the town's economy became focused more on oyster and seafood collection and packing. In the 1970s, the town transitioned to tourism.

In the original 1986 nomination form, the Saint Michaels Historic District consisted of 362 buildings, sites, and structures. Sixty of the buildings were noncontributing. Many of the structures were originally constructed in the 19th century, and used the Federal, Gothic Revival, or Italianate architectural styles. The entire town has a 19th-century appearance, and much of the Historic District can be observed by walking. The homes that contribute to the Historic District are privately owned, but many have been converted into bed and breakfasts.

The Chesapeake Maritime Museum is located along the Miles River and St. Michaels Harbor, in the northeast corner of the Historic District and further north. It features Chesapeake Bay exhibits such as ship building and oystering. The small Saint Michaels Museum is located within the Historic District at Saint Mary's Square. It focuses on 19th century Saint Michaels, and conducts walking tours of the Historic District. Talbot Street (Maryland Route 33) is the major street in Saint Michaels, and runs north–south through the Historic District. The street is lined with shops and restaurants housed in 19th century buildings.

Background

Saint Michaels is a small nautical-themed town located on Maryland's Eastern Shore.[1] It is situated along the Miles River, which leads to Chesapeake Bay.[Note 1] Boaters can get to the town's St. Michaels Harbor from nearby rivers or the Chesapeake Bay.[1] Traveling by automobile from major cities such as Annapolis or Baltimore, the most direct route to the Eastern Shore involves crossing the bay using the Chesapeake Bay Bridge.[3] Saint Michaels is part of Talbot County, and accessible by automobile via Maryland Route 33. In town, the road is known as Talbot Street and is the only road that passes through town. The town's Historic District is lined with shops and restaurants usually housed in well-preserved 19th century architecture.[4] The Saint Michaels Historic District is located in the center of town, and was added to the National Register on September 11, 1986.[5]

Beginning

The community that became Saint Michaels began in the mid-1600s as a trading post for tobacco farmers and trappers who took advantage of the deep–water port's access to the Chesapeake Bay.[6] The Christ Episcopal Church of St Michael Archangel parish was founded during the 1600s, and built a church near the Saint Michaels River (later named Miles River) and Broad Creek. This was the first building erected in the area.[6] The church's location meant that it could easily be reached by boat, which was convenient for the early settlers who typically lived along the banks of area creeks and coves.[7] The exact date the first church building was constructed is unknown. There is evidence it was built by at least 1672, and the structure had decayed enough that it was replaced in 1736.[7] A list of baptisms dating from 1672 to 1704 includes family names such as Arnett, Auld, Banning, Benson, Blades, Dawson, Harrison, Kemp, Merchant, and others.[8]

A small village grew near the church and harbor, inhabited mostly by craftsman involved in building or refitting ships plus shopkeepers who catered to the needs of the craftsman and sailors.[9] The village of about 100 people had no government other than the general laws of the province.[10] As the place where people congregated, the church took on the additional role of a place to meet for business. The community's name, Saint Michaels, came from the church name. The harbor of Saint Michaels became a place large English vessels brought goods for trade.[11]

Town of Saint Michaels

In 1778, British land agent James Braddock, working for Gildart and Gawith and Company of Liverpool (James Gildart and John Gawith), acquired much of the land near what became the town of Saint Michaels.[10] He had a surveyor measure a portion of his land into lots that were sold, including what became the town's public square. After his death in 1783, John Thompson gained control of Braddock's land and more plots were sold. Another prominent member of the community was Thomas Harrison, who was involved with importing goods from England and exporting tobacco and other goods from the area.[12] Upon his death in 1802, his son Samuel continued the business.[13]

Between 1804 and 1806, the village was re-surveyed and platted as three squares (or wards) plus the public square: Harrison's square at the north end, Thompson's square to the southwest, Braddock's square to the southeast end, and the public square known as Saint Mary's square.[14] In 1804, community members petitioned the General Assembly of the state for a charter for a corporate town named Saint Michaels. The petition was ratified on January 19, 1805, and became law.[15] Robert Dodson, John Dorgan, James Boid, and Thomas S. Haddaway were the town's original commissioners.[15] The new town's commissioners did not begin to execute their duties until 1807, and William Merchant replaced James Boid. Jason Dodson was added to the group of commissioners.[14] Town boundaries were marked and streets were named. Among the names used were Cherry, Chestnut, Locust, Mill, Mulberry, Talbot, Water, and Willow.[14]

Clippers and war

The Chesapeake Bay, with its access to Baltimore and Washington (via the Potomac River), was a major commercial waterway in the early 1800s—making it an obvious target for the British in their fight against the United States in the War of 1812.[16][17] Clipper ships, which were fast but could not carry large amounts of cargo, were used for fighting and evading the British.[18] It is thought that the design for Baltimore clippers had its beginning in Saint Michaels.[19][20] Master builder Thomas Kemp left Saint Michaels in 1803 to start his own shipbuilding business in Baltimore.[21] He purchased property at Baltimore's Fells Point two years later, and worked in shipbuilding and repair. His most famous clipper was the Chasseur, which was launched in December 1812 and one of the fastest ships of its time.[21] When an economic recession happened after the war, Kemp moved back to his Wade's Point farm near Saint Michaels.[21]

The town of Easton, county seat of Talbot County, was the largest town on Maryland's Eastern Shore and contained one of Maryland's four armories, making it a target for the British during the war. Boats and small vessels could use the Saint Michaels River to get within three miles (4.8 km) of Easton.[22] Saint Michaels, located on the mouth of the same river, was also a target because it was an outport for Easton and because of its shipbuilding.[18] The British conducted raids on St. Michaels twice in 1813.[23] Local militia successfully defended the town in both cases.[24][25]

Ship building

Ship building has been conducted in what became the town of St. Michaels since about 1670.[19] Shipbuilding in Saint Michaels prospered from 1780 to 1820, peaking around 1810.[26] The Harrisons, Haddaways, and Spencers, are all known to have had shipyards at or near St. Michaels in 1792.[27] At the 1810 shipbuilding peak, John Davis, Impey Dawson, Thomas L. Haddaway, Skinner Harris, Joseph Kemp, and John Wrightson all had shipyards within St. Michaels.[28] Colonel Perry Spencer, his brother Richard Spencer, William Harrison, and Thomas Hambleton had shipyards near the town with access to the St. Michaels River or Broad Creek (south of St. Michaels).[28]

Prosperity declined sharply after 1820, and some of the shipbuilding moved to Baltimore.[29] The end of the war with Great Britain and the depletion of lumber were the major reasons for the decline. Shipbuilding by that time was mostly for smaller craft, and was no longer the leading industry of Talbot County.[30] Shipbuilding enjoyed a revival around 1840, and typically there were two shipyards in St. Michaels.[31] At that time, steamships began to provide regular service between St. Michaels and Baltimore. Some of those packet boats were captained by members of the Dodson and Dawson families.[28] By 1882, St. Michaels had three active shipyards, which were run by Robert Lambdin and Sons, Thomas H. Kirby and Company, and Thomas L. Dawson. These shipyards constructed smaller crafts such as coasting schooners, pungies, and bugeyes.[32]

Seafood

After the 1820 decline of shipbuilding, the town's economy became more dependent on fishing and oystering. The construction of the Chesapeake & Delaware Canal at the northern end of the Chesapeake Bay opened new markets for oysters and seafood, causing a new prosperity for Saint Michaels starting around 1830.[33] The town's population increased from 499 in 1840 to 1,471 by 1880.[34] During that time, the oyster business grew beyond simply harvesting oysters. Businesses were now shucking (removing the oyster from its shell), packing and canning oysters.[31] In 1901, the town had the J.E. Watkins Oyster House that conducted shucking, packing, and canning of oysters at Navy Point Pier. It also had George Caulk's Oyster House on the St. Michaels River.[35] Near the river and Mulberry Street was C.W. Willey's Oyster House.[36]

In 1902, African Americans William Coulbourne and Frederick Jewett began a seafood packing house on Navy Point that operated until 1962.[37] Originally, the company processed fish, but eventually it focused on crab and crab meat. Jewett's method of grading crab meat is still used in the industry today.[37] In 1955, St. Michaels had three seafood companies: Bivalve Oyster Company, Coulborne and Jewett, and Harrison and Jarboe. All three produced shucked oysters, and two produced fresh-cooked crab meat.[38]

Today

Beginning in the 1970s, the community transformed itself to a focus on tourism.[39] Its Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum has approximately 95,000 visitors each year.[3] The town is walkable and has numerous restaurants, bed and breakfasts, and shops. It has about 1,000 permanent residents.[4] The Historic District has no traffic lights, no malls, and no major restaurant chains.[3] The small Saint Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square is located within the Historic District at Saint Mary's Square. Open on weekends, it focuses on 19th century Saint Michaels, and conducts walking tours of the Historic District every Saturday.[40]

List of structures

In the original 1986 nomination form, the St. Michaels Historic District consisted of 362 buildings, sites, and structures.[41] Sixty of the buildings were noncontributing. The district is described as "...a cohesive group of residential, commercial, and ecclesiastical buildings dating from the late 18th through early 20th centuries located within St. Michaels, a small town fronting the Miles River in western Talbot County, Maryland."[41]

The sortable table of the structures that are part of the historic district follows. If the year built is a range of years, the middle of the range is used. Since there are over 300 contributing structures, the list is incomplete. However, any structure mentioned in the original application to the National Register is in the list.[41] Some additional structures, mentioned in walking tours, have been added.[42] Three of the structures, by themselves, are listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The Old Inn was listed in 1980, the St. Michaels Mill in 1982, and the Cannonball House in 1983.[43][44][45]

| Name | MHT Code | Street | Coordinates | Image | Built | Notes and Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old Parsonage (a.k.a. Dr. Seth's House) | T-300 | Talbot Street, 210 N. (SW corner with Dodson Ave) | 38°47′18″N 76°13′31″W / 38.7882713°N 76.2252544°W |  |

1883 | The only Queen Anne style brick house in St. Michaels.[42] Built by Henry Clay Dodson. Donated in 1924 to the Union Methodist Church by Sarah Dodson Seth. The church sold the building in 1985.[46] |

| Thomas Dyott House (a.k.a. Captain Dodson House) | T-268 | Mill Street (St. Michaels Maritime Museum, faces harbor) | 38°47′14″N 76°13′14″W / 38.7872013°N 76.2205621°W |  |

1855 | Only three-story gallery in St. Michaels. Thomas Dyott built the house at Navy Point. Richard S. Dodson purchased the house in 1885, and it remained in the Dodson family until the early 1960s.[47] |

| Union United Methodist Church | T-571 | Railroad Avenue, 201 (corner with Fremont St) | 38°47′12″N 76°13′31″W / 38.7866117°N 76.2252831°W |  |

1895 | Goth Revival structure with three-story bell tower and a broach spire. Has a Victorian interior. Largest black church in town.[48] Designed by master craftsman Horace Turner.[49] |

| Gingerbread House | T-271 | Talbot Street, 103 S. (near Cherry St.) | 38°47′11″N 76°13′27″W / 38.7864028°N 76.2242879°W |  |

1879 | Victorian exterior with "Tee- and ell-plan".[50] |

| Town Hall Mall | T-555 | Talbot Street, 202 S. (West side) | 38°47′08″N 76°13′27″W / 38.7854849°N 76.2242038°W |  |

1875 | The two-story gable-front frame building is one of the town's largest. Originally intended to contain a Masonic Lodge Room and a town Hall[51] |

| Dorris House (a.k.a. Mount Pleasant) | T-258 | Talbot Street, 305 S. (corner with Mulberry St.) | 38°47′03″N 76°13′26″W / 38.7840325°N 76.2237989°W |  |

1806 | Built by merchant James Dooris. Molded watertable and jack arches.[52] |

| Christ Episcopal Church | T-260 | Talbot Street, 213 S. | 38°47′04″N 76°13′27″W / 38.7845325°N 76.2241011°W |  |

1878 | One of architectural centerpieces of town.[53] Full name of church is Christ Protestant Episcopal Church of St. Michael's Parish.[54] The Parish was established in 1672.[55] John Hollingsworth patented 50 acres (20 ha) around the shore of the river in 1664, and named it The Beach. Current church, built in 1878, is the fourth church building to occupy the site—part of land that was Hollingsworth's.[54] |

| Captain's Cabin | T-576 | Talbot Street, 214 S. (across from church) | 38°47′03″N 76°13′27″W / 38.7841195°N 76.2241444°W |  |

1865 | Large two-story commercial building with twisting chimney built by real estate agent James Benson.[56] |

| St. Luke's Methodist Church (Sardis Chapel) | T-259 | Talbot Street, 302-304 S. | 38°47′03″N 76°13′26″W / 38.7842077°N 76.2239011°W |  |

1871 | Italianate building.[57] |

| Leonard Funeral Home (a.k.a. Thomas Bruff House) | T-243 | Talbot Street, 312 S. (corner with Grace St.) | 38°47′01″N 76°13′25″W / 38.7837292°N 76.2236752°W |  |

1837 | Rare St. Michaels "telescope" house. Originally owned by ship's carpenter Thomas Bruff.[58][42] |

| Old Inn | T-257 | Talbot Street, 401 S. (corner with Mulberry St.) | 38°47′01″N 76°13′25″W / 38.7837292°N 76.2236752°W |  |

1816 | Listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[43] Earliest two-story engaged gallery in town. Wrightson Jones, believed to be a shipwright, built the inn shortly after he purchased some lots in 1816. In 1853, his son (also named Wrightson Jones) acquired property from other heirs.[59] |

| Clifton Hope House | T-560 | Talbot Street, 400 S. (corner with Grace St.) | 38°47′01″N 76°13′25″W / 38.7835148°N 76.2235463°W |  |

1888 | Queen Anne style with rare eyebrow windows that light the attic. Clifton Hope built house in 1888, and it remained in the family until 1968.[60] |

| Dr. Miller's Farmhouse (a.k.a. Spencer House or Berkeley's Hall) | T-255 | Talbot Street, 417 S. (corner with Chestnut St.) | 38°46′58″N 76°13′23″W / 38.782679°N 76.2230412°W |  |

1840 | Spencer family built the house and sold it to Dr. John Miller in 1847. House remained in Miller family until 1936. House was one of few built during recession period of late 1830s through 1840s. Brick house with small brick dairy or smokehouse.[61] |

| Colonel Kemp House | T-279 | Talbot Street, 412 S. (NW corner with Chestnut St.) | 38°46′57″N 76°13′23″W / 38.7825882°N 76.2229898°W |  |

1807 | Federal period brick structure. Colonel Joseph Kemp had this house built, and lived in it until his death around 1828. After his death, the house was purchased by the wife of William Kemp, and the house remained in that family until the early 20th century. Some of the woodwork in the interior may have been conducted by St. Michaels craftsman John Bruff.[62] |

| Arianna Sears House (a.k.a. Hotel Storey) | T-723 | Cherry Street, 104 | 38°47′12″N 76°13′25″W / 38.7866656°N 76.2235925°W |  |

1866 | House originally owned by Arianna Sears. In 1874, ownership transferred to her daughters, Mary True Storey and Anna Catherine Storey. Used as a hotel around 1900. Property sold out of the family in 1907.[63] |

| Alexander H. Seth House | T-570 | Cherry Street, 105 (corner with Cedar Street) | 38°47′12″N 76°13′25″W / 38.7866404°N 76.2237261°W |  |

1859 | House is covered by an atypical hip roof which survives with its seamed tin sheathing.[64] |

| The Snuggery | T-266 | Cherry Street, 203 (near Locust Street on north side) | 38°47′12″N 76°13′23″W / 38.7867436°N 76.2231102°W |  |

1700 | Log construction on front (now covered with siding) with Victorian interior including two marble mantle pieces.[65] |

| Kepner House | T-561 | Cherry Street, 204 (south side of street fronting harbor) | 38°47′12″N 76°13′22″W / 38.7867845°N 76.2228815°W |  |

1850 | Two-story on harbor.[66] |

| Henry Clay Dodson House (a.k.a. Shannahan House) | T-270 | Cherry Street (205, end of street) | 38°47′13″N 76°13′22″W / 38.7868237°N 76.2226671°W |  |

1873 | Built by Dodson. Bought by Norman M. Shannahan in 1911 and remained in family until 1987. Contrasts with other domestic architecture in town. Elaborate mansard roof and Colonial Revival porches.[67] |

| Dr. Dodson House | T-265 | Locust Street, 101 (corner with 200 Cherry St.) | 38°47′12″N 76°13′24″W / 38.7867036°N 76.2233108°W |  |

1800 | Originally a tavern built by Joseph or Samuel Harrison. Enlarged by Judge William H. Bruff. Also owned by Thomas Auld. Dr. Robert A. Dodson bought in 1878. Two-story brick built around 1800 with addition around later.[68] |

| Haddaway House | T-569 | Locust Street, 103 (east side near Carpenter Street) | 38°47′10″N 76°13′23″W / 38.7861595°N 76.2230333°W |  |

1808 | Shipbuilder Thomas L. Haddaway lived in this house before and during the War of 1812. A single-story double-pile house that dates to the early 19th century.[69] |

| Marshall House | T-563 | Locust Street (104, and Carpenter Street, NW corner) | 38°47′10″N 76°13′23″W / 38.7860968°N 76.2229553°W |  |

1803 | Originally owned by John Harrison. One of the better surviving interiors from the Federal period.[70] |

| Wrightson Jones House | T-598 | Locust Street, 201 (SE corner with Carpenter St.) | 38°47′10″N 76°13′23″W / 38.7860479°N 76.2229597°W |  |

1850 | Chamfered posts on porch, sawn brackets and balusters.[71] |

| Wickersham | T-56 | Locust Street, 203 | 38°47′09″N 76°13′22″W / 38.7857416°N 76.2227752°W |  |

1750 | Originally built by Robert Harwood, Dawson Baker Farm moved from Easton to St. Michaels in 2004.[72] |

| Franklin L. Tinker House (a.k.a. Thomas Harrison House) | T-591 | Green Street, 201 | 38°47′08″N 76°13′21″W / 38.7854227°N 76.2224973°W |  |

1798 | Oldest two-story frame structure still standing in town. Carpenter Thomas Harrison constructed house before 1798.[73] |

| Bruff-Mansfield House | T-262 | Green Street, 111 (NW corner with Locust Street) | 38°47′07″N 76°13′21″W / 38.7853589°N 76.222566°W |  |

1808 | Wheelwright John Bruff Sr. and later John F. Mansfield were among the early owners of this house. Bruff bought the lot from James Braddock in 1778. John Bruff Jr., a carpenter, inherited the house.[74] |

| Tarr House | T-261 | Green Street, 109 | 38°47′07″N 76°13′22″W / 38.7851417°N 76.2228317°W |  |

1805 | One and a half story with gabled dormers.[75] |

| Cannonball House | T-61 | Mulberry Street, 200 (near St. Mary's Square) | 38°47′03″N 76°13′21″W / 38.7842705°N 76.2225617°W |  |

1808 | Listed in the National Register of Historic Places. House hit by cannonball in British naval attack in 1813 during the War of 1812.[76] |

| Amelia Welby House (a.k.a. Captain Wetheral House) | T-254 | Mulberry Street, 209 (near Water Street) | 38°47′04″N 76°13′18″W / 38.7845645°N 76.2217381°W |  |

1783 | Wetheral operated shipyard and died in 1774. His property was bought by James Braddock in 1778. The house is possibly the oldest house remaining in St. Michaels. Amelia Coppuck Welby is thought to have born in this house, which was rented by her parents in 1819.[77] |

| Robert Lambdin House (a.k.a. The Cottage) | T-253 | Water Street 401, (corner with Mulberry Street, front entrance is on Mulberry) | 38°47′05″N 76°13′17″W / 38.784649°N 76.2214707°W |  |

1832 | Modest early 19th century house. Shipbuilder Robert Lambdin lived here, which is close to the water.[78] |

| St. Mary's Square Museum | T-252 | St. Mary's Square and Chestnut Street | 38°46′59″N 76°13′17″W / 38.7830176°N 76.2214675°W |  |

1850 | Built from reused timers from a steam mill.[79] |

| Granite Lodge | T-274 | St. Mary's Square, 403 | 38°47′01″N 76°13′20″W / 38.7834933°N 76.2221534°W |  |

1839 | Brick Greek Revival style originally a Methodist church.[80] |

| J. Harrison Kemp House | T-273 | Chestnut Street, 110 E. | 38°46′58″N 76°13′19″W / 38.7828498°N 76.2219151°W |  |

1857 | Largest and most architecturally distinctive dwelling along street consisting of late 19th century homes. Also known as the John W. Blades house for the oysterman who built it around 1857.[81] |

| John H. Blades House | T-630 | Chestnut Street, 112 E. | 38°46′59″N 76°13′17″W / 38.7830176°N 76.2214675°W |  |

1870 | Part of a group of well-preserved late 19th century dwellings.[82] |

| St. Michaels Mill | T-437 | Chew Avenue, 100 | 38°46′55″N 76°13′19″W / 38.7819101°N 76.2218608°W |  |

1890 | Listed in the National Register of Historic Places.[44] Center of commerce for 50 years. Eventually owned by James E. Watkins and Robert S. Dodson. Sold to Samuel Quillen and sons in 1920.[83] Built by Arthur K. Easter. Mill operated until 1972, and sold Just Right Flour.[42] |

| Rogers House (a.k.a. Crepe Myrtle Cottage) | T-272 | Chestnut Street, 112 W. | 38°46′55″N 76°13′29″W / 38.7818653°N 76.2246153°W |  |

1835 | Story-and-a-half frame house. John Dorgin, one of the original commissioners of the town, owned the property at one time.[84] |

| James Caulk House | T-742 | Chestnut Street, 119 W. | 38°46′54″N 76°13′29″W / 38.7817887°N 76.2248274°W |  |

1850 | Chamfered posts on porch, sawn brackets and balusters.[85] |

| Bruff House | T-241 | Thompson Street, 101 (north side) | 38°46′58″N 76°13′25″W / 38.7827103°N 76.2237132°W |  |

1790 | One of the oldest standing structures in town.[86] |

People

- Auld–Hugh Auld Sr. fought with the Talbot County Militia during the Revolutionary War.[87] His son, Hugh Auld Jr. was a lieutenant colonel with the 26th Maryland Militia during the War of 1812. His son, Thomas Auld (1795-1880) became a ship captain living in Talbot County, and had a brother named Hugh that was a shipbuilder living in Baltimore. Slave (and future prominent activist) Frederick Douglass spent time at both brothers' households, but was legally owned by Thomas.[88]

- Banning–Captain Robert Banning commanded a St. Michaels company of cavalry during the War of 1812.[89]

- Benson—Samuel Perry Benson (1757-1827), known as Perry Benson, was a captain in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, and a Major General in the Maryland state militia during the War of 1812.[90][91] He lived between St. Michaels and Easton near Oak Creek and the St. Michaels (now known as Miles) River.[91]

- Chaney– The Chaney brothers were free African Americans who were builders and owners of a house in St. Michaels around 1851.[92]

- Blades–Thomas W. Blades was postmaster of St. Michaels in 1856 and 1857.[93] Levin Blades was foreman of William Harrison's shipyard around 1810. This shipyard built large sea-going vessels, and was one of the biggest in Talbot County.[28]

- Braddock–James Braddock, was an agent for James Gildart and John Gawith and Company, of Liverpool.[94] James Braddock purchased Philip Wetheral's property in 1778, and began developing the area.[42]

- Bruff–Craftsman John Bruff Sr. (1740-1819) is listed as a wheelwright with a log shop in a 1783 tax assessment for St. Michaels.[41] He was also a joiner.[42] John Bruff Jr. (1774-1857), Thomas Bruff (1780-1857) was a ship's carpenter.[42] William H. Bruff was a judge in 1872.[42]

- Coulborne–African-American William Coulbourne was a partner in the Coulbourne and Jewett Seafood Packing Company in St. Michaels. The company was one of Maryland's most successful minority-owned businesses, and at one time during the 20th century was the largest employer in St. Michaels.[95]

- Davis—John Davis ran a shipyard in St. Michaels around 1810.[28]

- Dawson–Impey Dawson owned Dawson's wharf, a shipyard in St. Michaels during the War of 1812.[96]

- Dodson—Robert Dodson (1762-1824) was a farmer and businessman that owned several vessels that had routes between Baltimore and St. Michaels. He was one of the first commissioners of St. Michaels, active in the War of 1812, and is buried in the Methodist Cemetery at St. Michaels.[97] His eldest son is Captain William Dodson (1786-1833), who was in charge of his father's packet schooners.[97] During the War of 1812, Captain Dodson, holding the rank of lieutenant, was the artillerist in command of a fortification (Parrott's Point Battery) at St. Michaels that was attacked by the British.[89] During 1814 he fought the British while part of the United States Navy, and returned to St. Michaels after the war where he continued his old occupation.[98] His son, Captain Robert Auld Dodson (1808-1883) was also a sailor. He returned to St. Michaels after his father's death and continued the packet boat business. He was present at the Baltimore riot of 1861, where he denounced the attack on Massachusetts troops and had his life threatened by the rioters.[98] He was appointed postmaster of St. Michaels in 1878.[93] His brother, Edward Napoleon Dodson (1829-1899), was a steamboat captain.[99] Robert A. Dodson's son, Richard Stearns Dodson (1838-1897), was also a sailor and captained his father's schooner William K. Dodson. He gave up sailing for the hotel business in Baltimore, Pennsylvania, and then Norfolk. He also had property and businesses in St. Michaels, including the Saint Michaels and Miles River Steamboat Company.[100] At one time, the Dodson family owned Navy Point along the harbor in St. Michaels. This section is now (2021) occupied by the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum and a waterside restaurant.[47][101] Another son of Robert Auld Dodson was Henry Clay Dodson (1840-1914), who was a businessman and politician. He served as St. Michaels town commissioner and postmaster. He also served in the Maryland House of Delegates and Maryland Senate.[102] The son of Richard Stearns Dodson, Richard Slicer Dodson, was a banker and served in the Maryland General Assembly.[99]

- Dorris–James Dooris (Dorris) was a St. Michaels merchant from Ireland. He was a member of the Democratic-Republican Party, and served in the Maryland Legislature.[103]

- Dorgan–Craftsman John Dorgan is listed as a blacksmith in a 1783 tax assessment for St. Michaels.[41] He was one of the original commissioners of the town of St. Michaels.[104] Dorgan was involved in building as a ship-smith instead of a shipwright, and used others to construct his boats.[28]

- Douglass–Prominent activist Frederick Douglass (1818-1895) was a slave in St. Michaels from 1833 to 1836, returned to visit as a free man in 1877.[92][105]

- Dyott–Thomas Dyott was a storekeeper that lived by the water at Navy Point in 1861.[99]

- Easter–Arthur K. Easter built the St. Michaels Flour Mill around 1890.[42]

- Elliot—Edward Elliot is thought to have been the donor of the land used for the original Episcopal Church in St. Michaels.[7]

- Graham–Lieutenant John Graham (1778-1837) commanded at battery at Dawson's Wharf when the British attacked St. Michaels in 1813. The battery played an important role in preventing the British from entering the town.[106]

- Haddaway–Thomas S. Haddaway was one of the original commissioners of the town of St. Michaels.[104] Thomas L. Haddaway operated a shipyard near Locust Street in St. Michaels in the late 1700s.[42]

- Hambleton—One of the earliest settlers in the St. Michaels area was William Hambleton, who emigrated from Scotland around 1659.[107] Thomas Hambleton had a shipyard near St. Michaels around 1810, located near Hambleton's Island in Church Neck.[28] Samuel N. Hambleton was awarded a medal for his service in the 1813 Battle of Lake Erie under the command of Master commandant Oliver Perry, and named his farm Perry Cabin in honor of his leader.[107]

- Harris—Skinner Harris ran a shipyard in St. Michaels around 1810.[28]

- Harrison—Thomas Harrison was a house carpenter who constructed his house on Green Street around 1798.[42] His son, Samuel Harrison, moved a store to St. Michaels around 1810. He was also involved with making advances to ship builders of both money and supplies, owned a large mill.[30] William Harrison of Mount Pleasant, Church Neck, built large sea-going vessels in his shipyard near St. Michaels.[28]

- Hope—Clifton Hope was president of the St. Michaels Bank during the early 20th century.[108] He died in 1935.[60]

- Jewett—Frederick S. Jewett ran the Coulbourne and Jewett Seafood Packing Company, which was a successful African American business in the early 20th century. He established the packinghouse in 1902, and devised a crabmeat grading system still used today (2021).[109] Although the firm originally packed oysters, it eventually specialized in crabmeat.[99] Frederick Jewett's son, Elwood S. Jewett (1904-1977), took over the business in the 1940s. The company was sold during the 1960s when overharvesting caused may Chesapeake seafood packers to close.[95]

- Jones—Wrightson Jones was a shipbuilder at the time of the War of 1812, and had a shipyard on the southwest side of St. Michaels at Beverly on San Domingo Creek.[42] When the British attacked St. Michaels in 1813, he manned an artillery piece that was part of a two-gun battery at a wharf in town.[24] This battery, in combination with another, held off the British attackers.[106] Jones died in 1834.[110]

- Kemp–Thomas Kemp (1779-1824) was a master shipbuilder who made most of his famous ships in Baltimore.[111] It is thought that he learned his shipbuilding skills from Impey Dawson at his shipyard in St. Michaels.[111] In 1816, he moved back to the St. Michaels area at Wades Point (Bay Hundred) in Talbot County.[112] His sons were named Thomas H. Kemp and John W. Kemp.[113] His brother, Joseph, was also a shipbuilder.[114] Joseph Kemp had a shipyard in St. Michaels.[28] Captain Joseph Kemp, later Colonel Kemp, commanded a company of infantry from St. Michaels during the War of 1812. His company was named the Saint Michaels Patriotic Blues.[115] Joseph Kemp died in 1828.[62]

- Kirby—Shipbuilder Thomas H. Kirby (1824-1915) apprenticed at Robert Lambdin's shipyard in St. Michaels.[116] After working with George W. Lambdin in Baltimore during the Civil War, he returned to St. Michaels and began his own yard. In 1870 he moved his yard across the harbor to the former yard of Edward Willey, and purchased the site five years later after forming a partnership with vessel owner Frederick Lang. For 15 years, the yard was called Kirby & Lang. In 1890, Kirby bought out Lang and formed a partnership with two of his sons. The firm was called Thomas H. Kirby and Sons, and it was the last St. Michaels yard to build large wooden ships. The firm transitioned to maintenance and repair work, and produced smaller boats such as those used for gathering oysters.[116]

- Lambdin—Robert Lambdin (1799-1885) was a fourth-generation St. Michaels shipbuilder. Although his father died young, he apprenticed for his step-father shipbuilder John Graham.[116] After working about 20 years in Baltimore, he returned to St. Michaels and operated a small yard near Mulberry Street for 45 years. He taught all five of his sons the shipbuilding trade.[116] His eldest son, George Washington Lambdin (1832-1890) worked in Baltimore during the Civil War. He, along with brother William Adolphus Lambdin (1836-1903) became partners with their father in 1865. Another son, Robert Dawson Lambdin (1849-1938) began his apprenticeship in 1865. He left to work in the Washington Navy yard in 1869, and eventually returned to St. Michaels to build log canoes. The Lambdin yard closed in 1886.[116]

- Merchant—William Merchant owned the "Cannonball House" that was hit by a cannonball shot by the British during 1813.[42] He was a ship–smith.[117]

- Miller—Physician John Miller developed E. Chew Avenue and Marengo Street before that area became part of the town of St. Michaels.[42]

- Sears—Arianna Amanda Auld Sears (1826-1878) was a friend of Frederick Douglass.[118] She knew Douglass while he was a slave belonging to her father, Thomas Auld. She married a coal merchant named John L. Sears in 1843. Arianna became an opponent of slavery, and became friends with Douglass after an 1857 reunion.[118] William Sears

- Seth—Alexander H. Seth was a Justice of the Peace for the state of Maryland representing Talbot County in 1874.[119]

- Sewell—Jeremiah Sewell was a waterman in St. Michaels around 1865.[92]

- Spencer—James S. Spencer (1667-1714) had a farm close to St. Michaels around 1670.[120][121] Colonel Perry Spencer (1750-1822) had a shipyard in St. Michaels around 1810 that was one of the largest in town, and he also had a second yard on Broad Creek.[121][122] His brother Richard Spencer was also a shipbuilder.[122]

- Thompson—John Thompson took control of James Braddock's land in 1783 after Mr. Braddock's death, and continued dividing the area that became St. Michaels into lots for sale.[15]

- Turner—Horace Turner was the black builder involved with building the Union United Methodist Church, and built his own house on Dodson Avenue around 1904.[42]

- Welby—Poet laureate of Maryland Amelia B. Coppuck Welby (1819-1852), was born in a house in St. Michaels.[123] After she moved away, she became a poet who was praised by Edgar Allan Poe.[124][77]

- Wetheral—Captain Philip Wetheral operated a blacksmith shop and shipyard in St. Michaels. He died in 1774, and his property was later purchased by James Braddock who began developing what became the town of Saint Michaels.[42]

- Willey—Edward Willey (1814-1891) was a St. Michaels shipbuilder in the middle of the 19th century, and is credited with the 1840 revival of the industry in town.[30]

- Wrightson—John Wrightson had a shipyard in St. Michaels during the War of 1812.[18]

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

- 1 2 Seymour, Corey (July 16, 2021). "St. Michaels, a Sleepy Town off the Chesapeake Bay, Is the Perfect Stealth Weekend Escape". Vogue. New York, New York: Condé Nast. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 376–377

- 1 2 3 Owens, Donna M. (June 5, 2003). "St. Michaels is Awash in Charm". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 2, 2021.

- 1 2 Blades, Jay; Lay, Josh (August 26, 2018). "St. Michaels Is The East Coast Weekend Getaway You've Been Missing". Forbes. Jersey City, New Jersey: Integrated Whale Media Investments. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places - Digital Archive on NPGallery". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 375

- 1 2 3 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 376

- ↑ Leach 1905, pp. 427–438

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 380

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 381

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 377

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 378

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 379

- 1 2 3 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 384

- 1 2 3 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 382

- ↑ Atkins 2014, p. 179

- ↑ Atkins 2014, p. 181

- 1 2 3 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 162

- 1 2 Scharf 1879, p. 63

- ↑ Mashaw & MacClintock 2003, p. 43

- 1 2 3 Griffith, Jean (May 18, 2012). "Baltimore Clippers and Thomas Kemp of St. Michaels". Star Democrat (Easton, Maryland). Retrieved October 9, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 161

- ↑ Atkins 2014, p. 182

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 163–164

- ↑ "The Town that Fooled the British?". National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 386–387

- ↑ Ingraham 1898, p. 251

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 388

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 392

- 1 2 3 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 389

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 394

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 389–390

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 393

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 414

- ↑ Sanborn Map Company (1901). Image 15 of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Easton, Talbot County, Maryland (St. Michaels) (Map). New York, New York: Sanborn - Perris Map Company, Limited. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ↑ Sanborn Map Company (1901). Image 16 of Sanborn Fire Insurance Map from Easton, Talbot County, Maryland (St. Michaels) (Map). New York, New York: Sanborn - Perris Map Company, Limited. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- 1 2 "Watermen and the Seafood Industry". Talbot Historical Society. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ↑ United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service 1955, p. 10

- ↑ Pressley, Sue Anne (June 26, 1988). "Tourism's Wave of Change Hits St. Michaels". Washington Post. Retrieved October 27, 2021.

- ↑ "St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square". St. Michaels Museum. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - St. Michaels Historic District" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "A Walking Tour of Historic St. Michaels (2018)" (PDF). St. Michaels Museum at St. Mary's Square. Retrieved October 24, 2021.

- 1 2 "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - The Old Inn" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- 1 2 "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - St. Michaels Mill, Quillens Mill" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ↑ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form - Cannonball House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved October 23, 2021.

- ↑ "T-300 Henry Clay Dodson House (The Parsonage Inn)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- 1 2 "T-268 Captain Dodson House (Dyott House)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ "T-571 Union United Methodist Church" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ Vitabile 2007, p. 50

- ↑ "T-271 Gingerbread House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-555 Town Hall Mall (Commercial Building)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-258 Dorris House (Maryland National Bank)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-260 Christ Episcopal Church" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- 1 2 Vitabile 2007, p. 48

- ↑ "Christ Church St. Michaels breaks ground on Talbot Street Project". The Star Democrat (Easton, Maryland). December 17, 2021. p. 1.

In 1672, the Anglican Church of England established the Parish of St. Michaels on Shipping Creek, which is now St. Michaels Harbor.

- ↑ "T-576 Captain's Cabin" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ "T-259 St. Luke's Methodist Church (Sardis Chapel)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-243 Leonard or Harrison Funeral Home (Ortt House)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-257 The Old Inn" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- 1 2 "T-560 Clifton Hope House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-255 Berkeley Hall (Spencer House, Dr. Miller House)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- 1 2 "T-269 Kemp House Inn (Colonel Kemp House)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-723 Arianna Sears House (Hotel Storey)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 16, 2021.

- ↑ "T-570 Galt House (Alexander H. Seth House)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ "T-266 The Snuggery" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-561 Kepner House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ "T-270 H.C. Dodson House (Shannahan House)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ↑ "T-265 Dr. Dodson House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-569 Haddaway House (Butler House)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-563 Marshall" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ "T-598 Wrightson Jones House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ "T-56 Wickersham (Dawson Baker Farm)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 21, 2021.

- ↑ "T-591 Franklin L. Tinker House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ "T-62 Bruff-Mansfield House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-261 Tarr House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-61 Cannonball House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- 1 2 "T-254 Amelia Welby House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-253 Lambdin House (The Cottage)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ "T-252 St. Mary's Square Museum" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-274 Granite Lodge" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-273 J. Harrison Kemp House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ↑ "T-630 John H. Blades House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 1, 2021.

- ↑ "T-437 St. Michaels Mill (Quillens Mill)" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ "T-272 Rodgers House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ↑ "T-742 James Caulk House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- ↑ "T-241 Bruff House" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved September 28, 2021.

- ↑ Finkelman 2006, p. 104

- ↑ Finkelman 2006, pp. 104–105

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 157

- ↑ Ingraham 1898, pp. 265–266

- 1 2 Ingraham 1898, pp. 109–111

- 1 2 3 "St. Michaels Museum debuts a new look and new addition". Star–Democrat (Easton, Maryland). October 17, 2021. p. C6.

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 396

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 381–382

- 1 2 "Elwood small Jewett". University of Maryland Eastern Shore. Retrieved November 4, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 163

- 1 2 Hall 1912, p. 660

- 1 2 Hall 1912, p. 661

- ↑ Hall 1912, p. 662

- ↑ "History of the Parsonage Inn". The Parsonage Inn. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ↑ "Archives of Maryland Henry Clay Dodson". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 406

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 382–383

- ↑ "Archives of Maryland Frederick Douglass". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 167–168

- 1 2 Ingraham 1898, p. 275

- ↑ Maryland Bank Commissioner 1918, p. 67

- ↑ Vitabile 2007, p. 36

- ↑ "T-240 Beverly" (PDF). Maryland Historical Trust, State of Maryland. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- 1 2 Bourne 1954, p. 271

- ↑ Bourne 1954, p. 284

- ↑ Bourne 1954, pp. 287–288

- ↑ Bourne 1954, p. 287

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, p. 158

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Shipbuilding on the Chesapeake: Apprenticeships, Financing, and Changes in Technology for Builders of Wooden Vessels". Historic Naval Ships Association. Retrieved November 1, 2021.

- ↑ Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 388–389

- 1 2 Finkelman 2006, p. 70

- ↑ Maryland 1874, p. 808

- ↑ Ingraham 1898, p. 293

- 1 2 Earle & Skirven 1916, p. 34

- 1 2 Tilghman & Harrison 1915, pp. 387–388

- ↑ Vitabile 2007, p. 35

- ↑ Rutherford 1907, p. 147

References

- Atkins, Leslie (2014). Backroads & Byways of Chesapeake Bay: Drives, Daytrips and Weekend Excursions. Woodstock, Vermont: The Countryman Press. ISBN 978-1-58157-706-8. OCLC 918305276.

- Bourne, M. Florence (1954). "Thomas Kemp, Shipbuilder, and His Home, Wades Point". In Maryland Historical Society (ed.). Maryland Historical Magazine Vol. XLIX, No. 4 (December 1954) (PDF). Baltimore, Maryland: Maryland Historical Society. pp. 271–289. Retrieved October 22, 2021.

- Earle, Swepson; Skirven, Percy G., eds. (1916). Maryland's Colonial Eastern Shore; Historical Sketches of Counties and of Some Notable Structures. Baltimore, Maryland: Munder-Thomsen Press. OCLC 2004881. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of African American history, 1619-1895: From the Colonial Period to the Age of Frederick Douglass. Vol. 1, A-E. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19516-777-1. OCLC 1043702199.

- Hall, Clayton Colman, ed. (1912). Baltimore Its History and its People – Volume III—Biography. New York, New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company. OCLC 1178422. Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- Historic District Commission (St. Michaels), ed. (2021). Historic District Design Review Guidelines Town of St. Michaels (PDF). Saint Michaels, Maryland: Corporation of St. Michaels Talbot Co. MD. Retrieved October 15, 2021.

- Ingraham, Prentiss (1898). Land of Legendary Lore Sketches of Romance and Reality on the Eastern Shore of the Chesapeake. Easton, Maryland: The Gazette Publishing House. OCLC 1031797805. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- Leach, M. Atherton (1905). "Register of St. Michael's Parish, Talbot County, Maryland, 1672-1704". In Historical Society of Pennsylvania (ed.). The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography Vol. XXIX. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania. pp. 427–438. OCLC 1762062. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- Marine, William Matthew (1913). Dielman, Louis Henry (ed.). The British Invasion of Maryland, 1812-1815. Baltimore, Maryland: Society of the War of 1812 in Maryland. ISBN 978-0-80630-760-2. OCLC 3120839.

- Maryland (1874). Laws of the State of Maryland. Annapolis, Maryland: S.F. Mills and L.F. Colton. OCLC 42336599. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- Maryland Bank Commissioner (1918). Eighth Annual Report of the Bank Commissioner of the State of Maryland. Baltimore, Maryland: Baltimore City Printing and Binding Company. OCLC 2377528. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- Mashaw, Jerry L.; MacClintock, Anne U. (2003). Seasoned by Salt: A Voyage in Search of the Caribbean. Dobbs Ferry, New York: Sheridan House. OCLC 1225861717.

- Rutherford, Mildred Lewis (1907). The South in History and Literature; a Hand-book of Southern Authors, from the Settlement of Jamestown, 1607, to Living Writers. Atlanta, Georgia: Franklin-Turner Company. OCLC 7982315. Retrieved October 10, 2021.

- Scharf, J. Thomas (1879). History of Maryland from the Earliest Period to the Present Day - Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: John B. Piet. OCLC 4663774. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- Tilghman, Oswald; Harrison, Samuel A. (1915). History of Talbot county, Maryland, 1661-1861, Volume II. Baltimore, Maryland: Williams and Wilkins Company. OCLC 1541072. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service (1955). Around St. Michaels. Washington, District of Columbia: Bureau of Commercial Fisheries. OCLC 1690727. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- Vitabile, Christina (2007). Around St. Michaels. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-73854-258-4. OCLC 173176475.

External links

- St. Michaels Architectural Guidelines 1987

- St. Michaels tourism - Town of St. Michaels

- St. Michaels Attractions - Maryland Office of Tourism