| Population tables of U.S. cities |

|---|

|

| Cities |

| Urban areas |

| Populous cities and metropolitan areas |

| Metropolitan areas |

| Megaregions |

|

This is a list of capital cities of the United States, including places that serve or have served as federal, state, insular area, territorial, colonial and Native American capitals.

Washington has been the federal capital of the United States since 1800. Each U.S. state has its own capital city, as do many of its insular areas. Most states have not changed their capital city since becoming a state, but the capital cities of their respective preceding colonies, territories, kingdoms, and republics typically changed multiple times. There have also been other governments within the current borders of the United States with their own capitals, such as the Republic of Texas, Native American nations, and other unrecognized governments.

National capitals

.jpg.webp)

The buildings in cities identified in below chart served either as official capitals of the United States under the United States Constitution, or, prior to its ratification, sites where the Second Continental Congress or Congress of the Confederation met. The United States did not have a permanent capital under the Articles of Confederation.

The U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1787, and gave the Congress the power to exercise "exclusive legislation" over a district that "may, by Cession of particular States, and the acceptance of Congress, become the Seat of the Government of the United States."[1] The 1st Congress met at Federal Hall in New York.[2] In 1790, it passed the Residence Act, which established the national capital at a site along the Potomac River that would become Washington, D.C.[3] For the next ten years, Philadelphia served as the temporary capital.[4] There, Congress met at Congress Hall.[5] On November 17, 1800, the 6th United States Congress formally convened in Washington, D.C.[4] Congress has met outside of Washington only twice since: on July 16, 1987, at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of ratification of the Constitution;[6] and at Federal Hall National Memorial in New York on September 6, 2002, to mark the first anniversary of the September 11 attacks.[7] Both meetings were ceremonial.

| City | Building | Start date | End date | Duration | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second Continental Congress | |||||

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Independence Hall | July 4, 1776 (convened May 10, 1775, prior to independence) | December 12, 1776 | 5 months and 8 days | [8] |

| Baltimore, Maryland | Henry Fite House | December 20, 1776 | February 27, 1777 | 2 months and 7 days | [9] |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Independence Hall | March 5, 1777 | September 18, 1777 | 6 months and 13 days | [10] |

| Lancaster, Pennsylvania | Court House | September 27, 1777 | September 27, 1777 | 1 day | [10] |

| York, Pennsylvania | Court House (now Colonial Court House) | September 30, 1777 | June 27, 1778 | 8 months and 28 days | [10] |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | College Hall of the University of Pennsylvania

(Extensive damage to Independence Hall during the British Occupation of Philadelphia, necessitated this temporary meeting place) |

July 2, 1778 | July 13, 1778 | 11 days | [11][12][13] |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Independence Hall | July 14, 1778 | March 1, 1781 | 2 years, 7 months and 15 days | [14] |

| Congress of the Confederation | |||||

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Independence Hall | March 2, 1781 | June 21, 1783 | 2 years, 3 months and 19 days | [15] |

| Princeton, New Jersey[lower-alpha 1] | Nassau Hall | June 30, 1783 | November 4, 1783 | 4 months and 5 days | [15] |

| Annapolis, Maryland | Maryland State House | November 26, 1783 | August 19, 1784 | 8 months and 24 days | [15] |

| Trenton, New Jersey | French Arms Tavern | November 1, 1784 | December 24, 1784 | 1 month and 23 days | [15] |

| New York, New York | Federal Hall | January 11, 1785 | October 6, 1788 | 3 years, 11 months and 5 days | [15] |

| New York, New York | Walter Livingston House | October 6, 1788 | March 3, 1789 | 4 months and 25 days | [15] |

| United States Congress | |||||

| New York, New York | Federal Hall | March 4, 1789 | December 5, 1790 | 1 year, 9 months and 1 day | [15] |

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Congress Hall | December 6, 1790 | May 14, 1800 | 9 years, 5 months and 8 days[lower-alpha 2] | [15] |

| Washington, D.C. | United States Capitol | November 17, 1800[lower-alpha 3] | August 24, 1814[lower-alpha 4] | 13 years, 9 months and 7 days | [15] |

| Washington, D.C. | Blodgett's Hotel | September 19, 1814 | December 7, 1815 | 1 year, 2 months and 18 days | [18] |

| Washington, D.C. | Old Brick Capitol | December 4, 1815 | March 3, 1819 | 3 years, 2 months and 27 days | [19] |

| Washington, D.C. | United States Capitol | March 4, 1819 | Present | 204 years, 10 months and 10 days | [20] |

State capitals

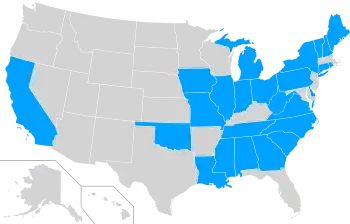

Each state has a capital that serves as the seat of its government. Ten of the thirteen original states and 15 other states have changed their capital city at least once; the last state to move its capital city was Oklahoma in 1910.

In the following table, the "Since" column shows the year that the city began serving as the state's capital (or the capital of the entities that preceded it). The MSA/µSA and CSA columns display the population of the metro area the city is a part of, and should not be construed to mean the population of the city's sphere of influence or that the city is an anchor for the metro area. Fields colored light yellow denote that the population is a micropolitan statistical area.

| State | Capital | Since | Area | Population (2020 US Census) | City rank in state | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City | MSA/µSA | CSA | |||||

| Alabama | Montgomery | 1846 | 159.8 sq mi (414 km2) | 200,603 | 386,047 | 476,207 | 3 |

| Alaska | Juneau | 1906 | 2,716.7 sq mi (7,036 km2) | 32,255 | 32,255 | 3 | |

| Arizona | Phoenix | 1912 | 517.6 sq mi (1,341 km2) | 1,608,139 | 4,845,832 | 4,899,104 | 1 |

| Arkansas | Little Rock | 1821 | 116.2 sq mi (301 km2) | 202,591 | 748,031 | 912,604 | 1 |

| California | Sacramento | 1854 | 97.9 sq mi (254 km2) | 524,943 | 2,397,382 | 2,680,831 | 6 |

| Colorado | Denver | 1867 | 153.3 sq mi (397 km2) | 715,522 | 2,963,821 | 3,623,560 | 1 |

| Connecticut | Hartford | 1875 | 17.3 sq mi (45 km2) | 121,054 | 1,213,531 | 1,482,086 | 4 |

| Delaware | Dover | 1777 | 22.4 sq mi (58 km2) | 39,403 | 181,851 | 7,379,700 | 2 |

| Florida | Tallahassee | 1824 | 95.7 sq mi (248 km2) | 196,169 | 384,298 | 8 | |

| Georgia | Atlanta | 1868 | 133.5 sq mi (346 km2) | 498,715 | 6,089,815 | 6,930,423 | 1 |

| Hawaii | Honolulu | 1845 | 68.4 sq mi (177 km2) | 350,964 | 1,016,508 | 1 | |

| Idaho | Boise | 1865 | 63.8 sq mi (165 km2) | 235,684 | 764,718 | 850,341 | 1 |

| Illinois | Springfield | 1837 | 54.0 sq mi (140 km2) | 114,394 | 208,640 | 308,523 | 7 |

| Indiana | Indianapolis | 1825 | 361.5 sq mi (936 km2) | 887,642 | 2,111,040 | 2,492,514 | 1 |

| Iowa | Des Moines | 1857 | 75.8 sq mi (196 km2) | 214,133 | 709,466 | 890,322 | 1 |

| Kansas | Topeka | 1856 | 56.0 sq mi (145 km2) | 126,587 | 233,152 | 5 | |

| Kentucky | Frankfort | 1792 | 14.7 sq mi (38 km2) | 28,602 | 75,393 | 746,045 | 15 |

| Louisiana | Baton Rouge | 1880 | 76.8 sq mi (199 km2) | 227,470 | 870,569 | 2 | |

| Maine | Augusta | 1832 | 55.4 sq mi (143 km2) | 18,899 | 123,642 | 10 | |

| Maryland | Annapolis | 1694 | 6.73 sq mi (17 km2) | 40,812 | 2,844,510 | 9,973,383 | 7 |

| Massachusetts | Boston | 1630 | 89.6 sq mi (232 km2) | 675,647 | 4,941,632 | 8,466,186 | 1 |

| Michigan | Lansing | 1847 | 35.0 sq mi (91 km2) | 112,644 | 541,297 | 5 | |

| Minnesota | Saint Paul | 1849 | 52.8 sq mi (137 km2) | 311,527 | 3,690,261 | 4,078,788 | 2 |

| Mississippi | Jackson | 1821 | 104.9 sq mi (272 km2) | 153,701 | 591,978 | 671,607 | 1 |

| Missouri | Jefferson City | 1826 | 27.3 sq mi (71 km2) | 43,228 | 150,309 | 15 | |

| Montana | Helena | 1875 | 14.0 sq mi (36 km2) | 32,091 | 83,058 | 6 | |

| Nebraska | Lincoln | 1867 | 74.6 sq mi (193 km2) | 291,082 | 340,217 | 361,921 | 2 |

| Nevada | Carson City | 1861 | 143.4 sq mi (371 km2) | 58,639 | 58,639 | 657,958 | 6 |

| New Hampshire | Concord | 1808 | 64.3 sq mi (167 km2) | 43,976 | 153,808 | 8,466,186 | 3 |

| New Jersey | Trenton | 1784 | 7.66 sq mi (20 km2) | 90,871 | 387,340 | 23,582,649 | 10 |

| New Mexico | Santa Fe | 1610 | 37.3 sq mi (97 km2) | 87,505 | 154,823 | 1,162,523 | 4 |

| New York | Albany | 1797 | 21.4 sq mi (55 km2) | 99,224 | 899,262 | 1,190,727 | 6 |

| North Carolina | Raleigh | 1792 | 114.6 sq mi (297 km2) | 467,665 | 1,413,982 | 2,106,463 | 2 |

| North Dakota | Bismarck | 1883 | 26.9 sq mi (70 km2) | 73,622 | 133,626 | 2 | |

| Ohio | Columbus | 1816 | 210.3 sq mi (545 km2) | 905,748 | 2,138,926 | 2,544,048 | 1 |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma City | 1910 | 620.3 sq mi (1,607 km2) | 681,054 | 1,425,695 | 1,498,149 | 1 |

| Oregon | Salem | 1855 | 45.7 sq mi (118 km2) | 175,535 | 433,353 | 3,280,736 | 3 |

| Pennsylvania | Harrisburg | 1812 | 8.11 sq mi (21 km2) | 50,099 | 591,712 | 1,295,259 | 9 |

| Rhode Island | Providence | 1900 | 18.5 sq mi (48 km2) | 190,934 | 1,676,579 | 8,466,186 | 1 |

| South Carolina | Columbia | 1786 | 125.2 sq mi (324 km2) | 136,632 | 829,470 | 951,412 | 2 |

| South Dakota | Pierre | 1889 | 13.0 sq mi (34 km2) | 14,091 | 20,745 | 9 | |

| Tennessee | Nashville | 1826 | 525.9 sq mi (1,362 km2) | 689,447 | 1,989,519 | 2,118,233 | 1 |

| Texas | Austin | 1839 | 305.1 sq mi (790 km2) | 961,855 | 2,283,371 | 4 | |

| Utah | Salt Lake City | 1858 | 109.1 sq mi (283 km2) | 199,723 | 1,257,936 | 2,701,129 | 1 |

| Vermont | Montpelier | 1805 | 10.2 sq mi (26 km2) | 8,074 | 59,807 | 285,369 | 6 |

| Virginia | Richmond | 1780 | 60.1 sq mi (156 km2) | 226,610 | 1,314,434 | 4 | |

| Washington | Olympia | 1853 | 16.7 sq mi (43 km2) | 55,605 | 294,793 | 4,953,421 | 23 |

| West Virginia | Charleston | 1885 | 31.6 sq mi (82 km2) | 48,864 | 258,859 | 779,969 | 1 |

| Wisconsin | Madison | 1838 | 68.7 sq mi (178 km2) | 269,840 | 680,796 | 910,246 | 2 |

| Wyoming | Cheyenne | 1869 | 21.1 sq mi (55 km2) | 65,132 | 100,512 | 1 | |

| [21][22][23] | |||||||

Insular area capitals

An insular area is a United States territory that is neither a part of one of the fifty states nor a part of the District of Columbia, the nation's federal district. Those insular areas with territorial capitals are listed below.

| Insular area | Capital | Since | Pop. (2010) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| American Samoa | Pago Pago | 1899 | 3,656 | Pago Pago refers to both a village and a group of villages, one of which is Fagatogo, the official seat of government stated in the territory's constitution. |

| Guam | Hagåtña | 1898 | 1,051 | Dededo is the area's largest village. |

| Northern Mariana Islands | Saipan | 1947 | 48,220 | Since the entire island, of 46 sq mi (120 km2), is organized as a single municipality, most publications designate the whole of Saipan as the Commonwealth's capital. Most government functions are based in the Capitol Hill village, except for the judicial branch which is located in Susupe. |

| Puerto Rico | San Juan | 1898 | 395,326 | The oldest continuously inhabited U.S. state or territorial capital, San Juan was originally called Puerto Rico while the island was called San Juan Bautista. |

| U.S. Virgin Islands | Charlotte Amalie | 1917 | 18,481 | Like the rest of the U.S. Virgin Islands, Charlotte Amalie (located on the island of Saint Thomas) has no local government and is directly administered by the territorial government. However, it has boundaries defined by the Virgin Islands Code and is recognized as a town by the U.S. Census Bureau. |

Former national capitals

Two of the 50 U.S. states, Hawaii and Texas, were once de jure sovereign states with diplomatic recognition from the international community.

Hawaii

During its history as a sovereign nation (Kingdom of Hawaii, 1795–1893; Republic of Hawaii, 1894–1898), five sites served as the capital of Hawaii:

- Waikīkī, 1795–1796

- Hilo, 1796–1803

- Honolulu, 1803–1812

- Kailua-Kona, 1812–1820

- Lahaina, 1820–1845

- Honolulu, 1845–1898

Annexed by the United States in 1898, Honolulu remained the capital, first of the Territory of Hawaii (1900–1959), and then of the state (since 1959).

Texas

During its history as a sovereign nation (Republic of Texas, 1836–1845), seven sites served as the capital of Texas:

- Washington (now Washington-on-the-Brazos), 1836

- Harrisburg (now part of Houston), 1836

- Galveston, 1836

- Velasco, 1836

- West Columbia, 1836

- Houston, 1837–1839

- Austin, 1839–1845

Annexed by the United States in 1845, Austin remains the capital of the state of Texas.

Native American capitals

Some Native American tribes, in particular the Five Civilized Tribes, organized their states with constitutions and capitals in Western style. Others, like the Iroquois, had long-standing, pre-Columbian traditions of a 'capitol' longhouse where wampum and council fires were maintained with special status. Since they did business with the U.S. Federal Government, these capitals can be seen as officially recognized in some sense.

Cherokee Nation

- New Echota 1825–1832

New Echota, now near Calhoun, Georgia, was founded in 1825, realizing the dream and plans of Cherokee Chief Major Ridge. Major Ridge chose the site because of its centrality in the historic Cherokee Nation which spanned parts of Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee and Alabama, and because it was near the confluence of the Conasauga and Coosawattee rivers. The town's layout was partly inspired by Ridge's many visits to Washington D.C. and to Baltimore, but also invoked traditional themes of the Southeastern ceremonial complex. Complete with the Council House, Supreme Court, Cherokee syllabary printing press, and the houses of several of the Nation's constitutional officers, New Echota served as the capital until 1832 when the state of Georgia outlawed Native American assembly in an attempt to undermine the Nation. Thousands of Cherokee would gather in New Echota for the annual National Councils, camping along the nearby rivers and holding long stomp dances in the park-like woods that were typical of many Southeastern Native American settlements.[24]

- Red Clay 1832–1838

The Cherokee National council grounds were moved to Red Clay, Tennessee, on the Georgia state line, in order to evade the Georgia state militia. The log cabins, limestone springs, and park-like woods of Red Clay served as the capital until the Cherokee Nation was removed to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) on the Trail of Tears.[24]

- Tahlequah 1839–1907, 1938–present

Tahlequah, in present-day Oklahoma, served as the capital of the original Cherokee Nation after Removal. After the Civil War, a turbulent period for the Nation which was involved in its own civil war resulting from pervasive anger and disagreements over removal from Georgia, the Cherokee Nation built a new National Capitol in Tahlequah out of brick. The building served as the capitol until 1907, when the Dawes Act finally dissolved the Cherokee Nation and Tahlequah became the county seat of Cherokee County, Oklahoma. The Cherokee National government was re-established in 1938 and Tahlequah remains the capital of the modern Cherokee Nation; it is also the capital of the United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians.

- Cherokee 20th century–present (Eastern Band of Cherokee)

Approximately four to eight hundred Cherokees escaped removal because they lived on a separated tract, purchased later with the help of Confederate Colonel William Holland Thomas, along the Oconaluftee River deep in the Smoky Mountains of North Carolina. Some Cherokees fleeing the Federal Army, sent for the "round up", fled to the remote settlements separated from the rest of the Cherokee Territory in Georgia and North Carolina, in order to remain in their homeland.[25] In the 20th century, their descendants organized as the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians; its capital is at Cherokee, North Carolina, in the tribally-controlled Qualla Boundary.

Muscogee Creek Nation

- Hot Springs, Arkansas c. 1837–1866

After Removal from their Alabama-Georgia homeland, the Creek national government met near Hot Springs which was then part of their new territory as prescribed in the Treaty of Cusseta. Because some Creeks fought with the Confederacy in the American Civil War, the Union forced the Creeks to cede over 3,000,000-acre (1,200,000 ha) - half of their land in what is now Arkansas.[26]

- Okmulgee 1867–1906

Served as the National capital after the American Civil War. It was probably named after Ocmulgee, on the Ocmulgee river in Macon, a principle Coosa and later Creek town built with mounds and functioning as part of the Southeastern ceremonial complex. However, there were other traditional Creek "mother-towns" before removal. The Ocmulgee mounds were ceded illegally in 1821 with the Treaty of Indian Springs.

Iroquois Confederacy

- Onondaga (Onondaga privilege c. 1450–present)

The Iroquois Confederacy or Haudenosaunee, which means "People of the Longhouse", was an alliance between the Five and later Six-Nations of Iroquoian language and culture of upstate New York.[27] These include the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Mohawk, and, after 1722, the Tuscarora Nations. Since the Confederacy's formation around 1450, the Onondaga Nation has held privilege of hosting the Iroquois Grand Council and the status of Keepers of the Fire and the Wampum —which they still do at the official Longhouse on the Onondaga Reservation.[28] Now spread over reservations in New York and Ontario, the Six Nations of the Haudenosaunee preserve this arrangement to this day in what they claim to be the "world's oldest representative democracy."[29]

Seneca Nation of Indians

The Seneca Nation republic was founded in 1848 and has two capitals that rotate responsibilities every two years. Jimerson Town was founded in the 1960s following the formation of the Allegheny Reservoir. The Senecas also have an administrative longhouse in Steamburg but do not consider that location to be a capital.

Navajo Nation

Window Rock (Navajo: Tségháhoodzání), Arizona, is a small city that serves as the seat of government and capital of the Navajo Nation (1936–present), the largest territory of a sovereign Native American nation in North America. It lies within the boundaries of the St. Michaels Chapter, adjacent to the Arizona and New Mexico state line. Window Rock hosts the Navajo Nation governmental campus which contains the Navajo Nation Council, Navajo Nation Supreme Court, the offices of the Navajo Nation President and Vice President, and many Navajo government buildings.

Unrecognized national capitals

There have been a handful of self-declared or undeclared nations within the current borders of the United States which were never officially recognized as legally independent sovereign entities; however, these nations did have de facto control over their respective regions during their existence.

Colonies of British America

Prior to the independence of the United States from Great Britain, declared July 4, 1776 in the Declaration of Independence and ultimately secured in the American Revolutionary War, several congresses were convened on behalf of some of the colonies of British America. However, these bodies did not address the question of independence from England, and therefore did not designate a national capital. The Second Continental Congress encompassed the period during which the United States declared independence, but had not yet established a permanent national capital.

| City | Building | Start date | End date | Duration | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albany Congress | |||||

| Albany, New York | Stadt Huys | June 19, 1754 | July 11, 1754 | 22 days | [30] |

| Stamp Act Congress | |||||

| New York, New York | City Hall | October 7, 1765 | October 25, 1765 | 23 days | [31] |

| First Continental Congress | |||||

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Carpenters' Hall | September 5, 1774 | October 26, 1774 | 1 month and 21 days | [32] |

| Second Continental Congress | |||||

| Philadelphia, Pennsylvania | Independence Hall | May 10, 1775 | July 4, 1776 (continuing after independence until December 12, 1776) | 1 year, 1 month and 24 days | [8] |

Vermont Republic

Before joining the United States as the fourteenth state, Vermont was an independent republic known as the Vermont Republic (1777–1791). Three cities served as the capital of the Republic:

- Westminster, 1777

- Windsor, 1777–?

- Castleton, ?–1791

The current capital of the State of Vermont is Montpelier.

State of Franklin

The State of Franklin was an autonomous, secessionist United States territory created not long after the end of the American Revolution from territory that later was ceded by North Carolina to the federal government. Franklin's territory later became part of the state of Tennessee. Franklin was never officially admitted into the Union of the United States and existed for only four years.

- Jonesborough, Tennessee, 1784–1785

- Greeneville, Tennessee, 1785–1788

State of Muskogee

The State of Muskogee was a Native American state in Spanish Florida created by the Englishman William Augustus Bowles, who was its "Director General", author of its Constitution, and designer of its flag.[33] It consisted of several tribes of Creeks and Seminoles. It existed from 1799 to 1803. It had one capital:

- Miccosukee,[34] 1799–1803

Republic of West Florida

The Republic of West Florida was a short-lived nation that broke away from the territory of Spanish West Florida in 1810. It comprised the Florida Parishes of the modern state of Louisiana and the Mobile District of the modern states of Mississippi and Alabama. (The Republic of West Florida did not include any part of the modern state of Florida.) Ownership of the area had been in dispute between Spain and the United States, which claimed that it had been included in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803. Within two months of the settlers' rebellion and the declaration of an independent nation, President James Madison sent American forces to peaceably occupy the new republic. It was formally annexed by the United States in 1812 over the objections of Spain and the land was divided between the Territory of Orleans and Territory of Mississippi. During its brief existence, the capital of the Republic of West Florida was:

Republic of Indian Stream

The Republic of Indian Stream was an unrecognized independent nation within the present state of New Hampshire.

- The area that would become Pittsburg, New Hampshire, 1832–1835

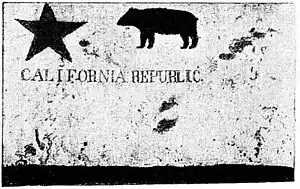

California Republic

Before being annexed by the United States in 1848 (following the Mexican–American War), a small portion of north-central California declared itself the California Republic, in an act of independence from Mexico, in 1846 (see Bear Flag Revolt). The republic only existed a month before it disbanded itself to join the advancing American army; its claimed territory later became part of the United States as a result of the Mexican Cession.

The very short-lived California Republic was never recognized by the United States, Mexico or any other nation. The flag, featuring a silhouette of a California grizzly bear, a star, and the words "California Republic", became known as the Bear Flag and was later the basis for the official state flag of California.

There was one de facto capital of the California Republic:

- Sonoma, 1846

Confederate States

The Confederate States of America (C.S.A.) had two capitals during its existence. The first capital was established February 4, 1861, in Montgomery, Alabama, and remained there until it was moved to Richmond, Virginia, on May 29, 1861, after Virginia seceded on May 23.

The individual state capitals remained the same in the Confederacy as they had been in the Union (U.S.A.), although as the advancing Union Army used those cities for military districts, some of the Confederate governments were relocated or moved out of state, traveling along with secessionist armies.

- Montgomery, Alabama, February 4, 1861 – May 29, 1861

- Richmond, Virginia, May 29, 1861 – April 3, 1865

Free State of Jones

In 1863 and 1864, Jones County, Mississippi revolted against Confederate rule and became practically independent under the name Free State of Jones. The Free State fought a number of skirmishes with Confederate troops. By the spring of 1864 the Jones County rebels had taken effective control of the county from the Confederate government, raised an American flag over the courthouse in Ellisville, and sent a letter to Union General William T. Sherman declaring Jones County's independence from the Confederacy.[35]

Scholars have disputed whether the county truly seceded, with some concluding it did not fully secede. Lack of documentation makes the situation difficult to assess. The rebellion in Jones County has been variously characterized as consisting of local skirmishes to being a full-fledged war of independence.[35]

Historical state, colonial, and territorial capitals

Most of the original Thirteen Colonies had their capitals occupied or attacked by the British during the American Revolutionary War. State governments operated where and as they could. The City of New York was occupied by British troops from 1776 to 1783. A similar situation occurred during the War of 1812, during the American Civil War in many Confederate states, and during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680–1692 in New Mexico.

Twenty-two state capitals have been a capital longer than their state has been a state, since they served as the capital of a predecessor territory, colony, or republic. Boston, Massachusetts, has been a capital city since 1630; it is the oldest continuously running capital in the United States. Santa Fe, New Mexico, is the oldest capital city, having become capital in 1610 and interrupted only by the aforementioned Pueblo Revolt. An even older Spanish city, St. Augustine, Florida, served as a colonial capital from 1565 until about 1820, more than 250 years.

The table below includes the following information:

- The state, the year in which statehood was granted, and the state's capital are shown in bold type. NOTE: For the first thirteen states, formerly the Thirteen Colonies of Great Britain on the Atlantic seaboard, the year of statehood is shown as 1776 (United States Declaration of Independence) rather than the subsequent year each state ratified the 1787 United States Constitution. (See List of U.S. states by date of admission to the Union.)

- The year listed for each capital is the starting date; the ending date is the starting date for the successor unless otherwise indicated.

- In many cases, capital cities of historical jurisdictions were outside of a state's present borders. (Those cities are generally indicated with the two-letter abbreviation for the U.S. state in which the former administrative capital is now located.)

See also

- History of the United States

- List of largest cities of U.S. states and territories by population

- List of state and territorial capitols in the United States

- List of states and territories of the United States

- Lists of capitals

- Outline of United States history

- Relocation of the United States Government to Trenton (1799)

- Territorial evolution of the United States

- Territories of the United States

- Timeline of geopolitical changes

Explanatory notes

- ↑ Congress was forced to move from Philadelphia due to a riot of angry soldiers. See: Pennsylvania Mutiny of 1783

- ↑ Government offices were evacuated to Trenton, New Jersey, from August to November 1799 following an outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia.

- ↑ The District of Columbia was formed February 27, 1801, with the District of Columbia Organic Act of 1801. The city of Washington was founded in 1791 and construction of the new capital began while it was still part of Maryland. President John Adams moved to the White House on November 1, 1800 and the 6th United States Congress held its first session in Washington on November 17, 1800.[16]

- ↑ President James Madison fled to the home of Caleb Bentley in Brookeville, Maryland following the burning of Washington on August 24–25, 1814. As such, the town claims to have been the "U.S. Capital for a Day" despite the fact that Congress never met there.[17]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The Spanish name La Florida originally referred to all of the American continent north of Mexico. As other European nations colonized North America, the extent of La Florida shrank to encompass only the Spanish territorial claims in the southeastern portion of the present United States.

- 1 2 3 The name Arkansas has been pronounced and spelled in a variety of fashions. The region was organized as the Territory of Arkansaw on July 4, 1819, but the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Arkansas on June 15, 1836. The name was historically pronounced /ˈɑːrkənsɔː/, /ɑːrˈkænzəs/, and several other variants. In 1881, the Arkansas General Assembly passed the following concurrent resolution (Arkansas Statutes, Title 1, Chapter 4, Section 105):

Whereas, confusion of practice has arisen in the pronunciation of the name of our state and it is deemed important that the true pronunciation should be determined for use in oral official proceedings.

And, whereas, the matter has been thoroughly investigated by the State Historical Society and the Eclectic Society of Little Rock, which have agreed upon the correct pronunciation as derived from history, and the early usage of the American immigrants.

Be it therefore resolved by both houses of the General Assembly, that the only true pronunciation of the name of the state, in the opinion of this body, is that received by the French from the Native Americans and committed to writing in the French word representing the sound. It should be pronounced in three (3) syllables, with the final "s" silent, the "a" in each syllable with the Italian sound, and the accent on the first and last syllables. The pronunciation with the accent on the second syllable with the sound of "a" in "man" and the sounding of the terminal "s" is an innovation to be discouraged.

Citizens of the State of Kansas often pronounce the Arkansas River /ɑːrˈkænzəs/ in a manner similar to the common pronunciation of the name of their state. - ↑ Due to flooding in Sacramento, San Francisco served as a temporary capital from January 24, 1862 to May 15, 1862. See "California's State Capitols 1850–present" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2013.

- ↑ From December 3, 1859, to December 3, 1861, Denver City was formally the City of Denver, Auraria, and Highland.

- ↑ On November 15, 1902, the City of Denver became the City and County of Denver.

- ↑ Note: The Louisiana Capitals information may be incorrect or incomplete. See "Louisiana History". Archived from the original on June 15, 2006. Retrieved June 28, 2006. and elsewhere.

References

- ↑ "Article 1 Section 8 Clause 17". Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "Farewell to New York". U.S. Senate. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ Drexler, Ken (April 21, 2020). "Residence Act: Primary Documents in American History: Introduction". Library of Congress Research Guides. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- 1 2 González, Jennifer (November 17, 2015). "On This Day: Congress Moves to Washington, D.C. | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress". Library of Congress Blogs. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "Congress Hall - Independence National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". National Park Service. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "Ceremonial Meeting of Congress in Philadelphia for Bicentennial of Constitution". US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "A Special Session at Federal Hall in New York City". US House of Representatives: History, Art & Archives. September 6, 2002. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- 1 2 Riley, Edward M. (1953). "The Independence Hall Group". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 43 (1): 7–42. doi:10.2307/1005661. ISSN 0065-9746. JSTOR 1005661.

- ↑ "Buildings of the Department of State Henry Fite's House, Baltimore Dec. 20, 1776—Feb. 27, 1777". Office of the Historian. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Klein, Christopher. "8 Forgotten Capitals of the United States". HISTORY. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "Meeting Places for the Continental Congresses and the Confederation Congress, 1774–1789". Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- ↑ "College Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: July 2, 1778 to July 20, 1778". unitedstatescapitals.org.

- ↑ see also Ford, Worthington C.; Hunt, Gaillard; Fitzpatrick, John C.; Hill, Roscoe R. (eds.). "Journals of the Continental Congress (JCC) 1774–1789". A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Databases, 1774–1875. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. 1: 13, 104, 114 – via Library of Congress.

- ↑ "Meeting Places for the Continental Congresses and the Confederation Congress, 1774–1789". Retrieved January 30, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "The Nine Capitals of the United States". U.S. Senate. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ Carter II, Edward C. (1971–1972), "Benjamin Henry Latrobe and the Growth and Development of Washington, 1798-1818", Records of the Columbia Historical Society: 139

- ↑ "A Brief History". Town of Brookeville, Maryland. 2006. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved October 7, 2008.

- ↑ "The Senate Convenes in Emergency Quarters". U.S. Senate. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "On This Day: December 4, 1815". U.S. Senate. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "Meeting Places and Quarters". U.S. Senate. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ Bureau, US Census. "City and Town Population Totals: 2020". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ↑ Bureau, US Census. "Metropolitan and Micropolitan Population Totals: 2020". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- ↑ Bureau, US Census. "Combined Statistical Area Population Totals and city rankings: 2020". The United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

- 1 2 Ehle, John (1988). Trail of Tears: The Rise and Fall of the Cherokee Nation. New York: Anchor Books Doubleday. ISBN 0385239548.

- ↑ "Qualla Boundary | NCpedia". www.ncpedia.org. Retrieved September 18, 2017.

- ↑ "Muscogee Creek Nation -Culture/history". Muscogee Creek Nation.

- ↑ nysmuseum (September 30, 2014), Haudenosaunee or Iroquois?, archived from the original on December 12, 2021, retrieved January 24, 2017

- ↑ "Haudenosaunee Confederacy". www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Haudenosaunee Confederacy". www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ↑ "Albany Congress | United States history [1754]". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "History & Culture - Federal Hall National Memorial". National Park Service. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ "Buildings of the Department of State - Carpenters' Hall, Philadelphia Sept. 5, 1774—Oct. 26, 1774". Office of the Historian. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ↑ Landers, Jane (2010). Atlantic Creoles in the Age of Revolutions. London: Harvard University Press. pp. 102–103.

- ↑ The State of Muskogee, State Flags of Florida, Cultural, Historical and Information Programs, Office of Cultural and Historical Programs website, Florida Department of State, Government of Florida, retrieved October 31, 2007.

- 1 2 Kelly, James R. Jr. (April 2009). "Newton Knight and the Legend of the Free State of Jones". mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov. Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ↑ "Florida Timeline: Florida Senate Kids". archive.flsenate.gov. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ↑ Capitals of Alabama. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Updated October 29, 2001. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ Frequently Asked Questions About Alaska Archived June 13, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Statewide Library Electronic Doorway. Updated September 21, 2004. Accessed June 9, 2005; based on Alaska Blue Book 1993–94, 11th ed., Juneau, Department of Education, Division of State Libraries, Archives & Museums. ExploreNorth: The History of Sitka Archived February 18, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Department of Community and Economic Development, Alaska Community Database Online. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ Capitals before the Capitol Archived March 7, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ Educational Materials: Facts Archived June 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Arkansas Secretary of State. Accessed June 9, 2005. Washington State Park 19th century village in SW Arkansas Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism, Confederate Capital Old Division of State Parks. 2003. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ E. Dotson Wilson (2006). Ebbert, Brian S. (ed.). California's Legislature (PDF). Sacramento, California: State of California. pp. 157–165. Retrieved October 3, 2006.

- ↑ Early Capitol and Legislative Assembly Locations Colorado State Archives, Colorado State Capitol Virtual Tour. Updated June 20, 2003. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ Florida State History. Florida Division of Historical Resources.

- ↑ Jackson, Edwin L. Story of Georgia's Capitols and Capital Cities Archived October 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Carl Vinson Institute of Government. University of Georgia. 1988

- ↑ Chronological History of Idaho Archived August 7, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Idaho Office of the Governor. Created 2000. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- 1 2 3 Clarke, S.A. (1905). Pioneer Days of Oregon History. J.K. Gill Company.

- ↑ Past Capitols; based on Illinois Bluebook, 1975–1976. Created March 5, 2005. Accessed June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Sabin, Henry. Making of Iowa, chapter 24: Locating a Capital. Originally published 1900 by A. Flanagan Co. of Chicago and New York; published online by Iowa History Project, posted August 25, 2004. Accessed June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Harding, Eldon. Stories from the Kansas State Capital: Choosing a Capital City--Why Topeka? Archived March 12, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Kansas State Historical Society. April 2001. Accessed June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, Daniel (1988). Ghost Towns of Kansas. University Press of Kansas. pp. 61–65. ISBN 0700603689.

- ↑ Kentucky's State Capitols Archived August 13, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives. Accessed July 24, 2006.

- ↑ Students Questions Frequently Ask Archived March 13, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Maine State Senate. Accessed June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Historical Chronology. Maryland State Archives. Accessed July 24, 2006.

- ↑ Michigan in Brief State of Michigan. Updated March 7, 2005. Accessed June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Saint Paul's 150th birthday Archived April 11, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. City of Saint Paul, Minnesota. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ Bunn, Mike and Clay Williams, Capitals and Capitols: The Places and Spaces of Mississippi's Seat of Government Archived May 11, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society Online. Posted September 2003. Accessed June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Lambert, Kirby. Montana's crown jewel of architecture: The Montana state capitol Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Montana: The Magazine of Western History, Montana Historical Society. Summer 2002. Accessed June 10, 2005.

- ↑ Rocha, Guy Nevada State Archives Historical Myth a Month: Myth #28, Las Vegas: Nevada's Next State Capital Archived August 22, 2003, at the Wayback Machine. Updated July 14, 2003. Accessed June 9, 2005; originally published as Sierra Sage, Carson City/Carson Valley, Nevada. May 1998 edition.

- ↑ New Hampshire Senate Page For Kids. New Hampshire General Court. Accessed June 9, 2005. New Hampshire History in Brief. New Hampshire Division of Historical Resources. Created 1989. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ Oregon Legislative Assembly History. Oregon State Archives. Accessed February 17, 2012.

- ↑ The History of Pennsylvania's Capital. Pennsylvania Department of Education. Accessed July 24, 2006.

- ↑ Capital Cities. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. 2002. Accessed March 12, 2006.

- ↑ Early History of Montpelier, Vermont Archived February 12, 2005, at the Wayback Machine. Vermont Historical Society. Accessed June 9, 2005; adapted from Esther Munroe Swift, Vermont Place-Names: Footprints of History, 1977, 1996, and Montpelier Heritage Group, Three Walking Tours of Montpelier, Vt., 1991.

- ↑ About Our Capital Archived June 25, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Virginia General Assembly. Accessed July 20, 2006.

- ↑ The History of Olympia. City of Olympia. Accessed June 9, 2005.

- ↑ Cravens, Stanley H."Capitals and Capitols in Early Wisconsin" Archived June 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine. Wisconsin Blue Book Archived February 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, 1983–1984 edition.

- ↑ Saban, Mary Thompson, Wyoming Sage: Brief History of Wyoming. Updated January 17, 2004. Accessed June 10, 2005.

Further reading

- Christian Montes. American Capitals: A Historical Geography (University of Chicago Press; 2014) 394 pages; scholarly study of geographic and other factors that have shaped the designation of capitals in all 50 states