| History of Louisiana |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of the area that is now the U.S. state of Louisiana, can be traced back thousands of years to when it was occupied by indigenous peoples. The first indications of permanent settlement, ushering in the Archaic period, appear about 5,500 years ago. The area that is now Louisiana formed part of the Eastern Agricultural Complex. The Marksville culture emerged about 2,000 years ago out of the earlier Tchefuncte culture. It is considered ancestral to the Natchez and Taensa peoples. Around the year 800 CE, the Mississippian culture emerged from the Woodland period. The emergence of the Southeastern Ceremonial Complex coincides with the adoption of maize agriculture and chiefdom-level complex social organization beginning in circa 1200 CE. The Mississippian culture mostly disappeared around the 16th century, with the exception of some Natchez communities that maintained Mississippian cultural practices into the 1700s.

European influence began in the 1500s, and La Louisiane (named after Louis XIV of France) became a colony of the Kingdom of France in 1682, before passing to Spain in 1763. Louisiana became part of the Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803. The U.S. would divide that area into two territories, the Territory of Orleans, which formed what would become the boundaries of Louisiana, and the District of Louisiana. Louisiana was admitted as the 18th state of the United States on April 30, 1812. The final major battle in the War of 1812, the Battle of New Orleans, was fought in Louisiana and resulted in a U.S. victory.

Antebellum Louisiana was a leading slave state, where by 1860, 47% of the population was enslaved. Louisiana seceded from the Union on January 26, 1861, joining the Confederate States of America. New Orleans, the largest city in the entire South at the time, and strategically important port city, was taken by Union troops on April 25, 1862. After the defeat of the Confederate Army in 1865, Louisiana would enter the Reconstruction era (1865–1877). During Reconstruction, Louisiana was subject to U.S. Army occupation, as part of the Fifth Military District.

Following Reconstruction in the 1870s, white Democrats had regained political control in the state. In 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Plessy v. Ferguson case ruled that "separate but equal" facilities were constitutional. The lawsuit stemmed from 1892 when Homer Plessy, a mixed-race resident of New Orleans, violated Louisiana's Separate Car Act of 1890, which required "equal, but separate" railroad accommodations for white and non-white passengers. This court decision upheld Jim Crow laws that had started to form in the 1870s. In 1898, white Democrats in the Louisiana state legislature passed a new disfranchising constitution, whose effects were immediate and long-lasting. The disfranchisement of African Americans in the state did not end until national legislation passed during the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s.

In the early-to-mid 20th century, many African Americans would leave the state in the Great Migration. They moved to mainly urban areas in the North and Midwest. The Great Depression of the 1930s would hit the states economy hard, as mostly agricultural state at the time, farm prices had dropped to all-time lows. In the states urban areas such as New Orleans, many warehouses and businesses had closed, leaving many unemployed. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration would help flow money into the state, providing employment opportunities for Louisiana projects. World War II would help accelerate the industrialization of Louisiana's economy and provide further economic growth.[1][2] In the 1950s and 1960s, the Civil Rights movement had started to gain national attention, and with the passing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, disfranchisement of African Americans in the state had ended.

In the late 20th Century, Louisiana saw rapid industrialization and rise of economic markets such as oil refineries, petrochemical plants, foundries, along with industries of produce foods, fishing, transportation equipment, and electronic equipment. Tourism also became important to the Louisiana economy, with Mardi Gras becoming a known major celebration held annually since 1838.[3] In 2005, Hurricane Katrina struck Louisiana and surrounding areas in the Gulf of Mexico, resulting in major damages. A $15 billion new levee system built in New Orleans would take place from 2006 to 2011.

Prehistory

Lithic stage

The Dalton tradition is a Late Paleo-Indian and Early Archaic projectile point tradition, appearing in much of Southeast North America around 8500–7900 BC.

Archaic period

During the Archaic period, Louisiana was home to the earliest mound complex in North America and one of the earliest dated complex constructions in the Americas. The Watson Brake site is an arrangement of human-made mounds located in the floodplain of the Ouachita River near Monroe in northern Louisiana. It has been dated to about 3400 BC. The site appears to have been abandoned about 2800.[4]

By 2200 BC, during the Late Archaic period the Poverty Point culture occupied much of Louisiana and was spread into several surrounding states. Evidence of this culture has been found at more than 100 sites, including the Jaketown Site near Belzoni, Mississippi. The largest and best-known site is near modern-day Epps, Louisiana at Poverty Point. The Poverty Point culture may have hit its peak around 1500, making it the first complex culture, and possibly the first tribal culture, not only in the Mississippi Delta but in the present-day United States. Its people were in villages that extended for nearly 100 miles across the Mississippi River.[5] It lasted until approximately 700 BC.

Woodland period

The Poverty Point culture was followed by the Tchefuncte and Lake Cormorant cultures of the Tchula period, local manifestations of Early Woodland period. These descendant cultures differed from Poverty Point culture in trading over shorter distances, creating less massive public projects, completely adopting ceramics for storage and cooking. The Tchefuncte culture were the first people in Louisiana to make large amounts of pottery. Ceramics from the Tchefuncte culture have been found in sites from eastern Texas to eastern Florida, and from coastal Louisiana to southern Arkansas.[6] These cultures lasted until 200 AD.

The Middle Woodland period started in Louisiana with the Marksville culture in the southern and eastern part of the state[7] and the Fourche Maline culture in the northwestern part of the state. The Marksville culture takes its name from the Marksville Prehistoric Indian Site in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. These cultures were contemporaneous with the Hopewell cultures of Ohio and Illinois, and participated in the Hopewell Exchange Network.

At this time populations became more sedentary and began to establish semi-permanent villages and to practice agriculture,[8] planting various cultigens of the Eastern Agricultural Complex. The populations began to expand, and trade with various non-local peoples also began to increase. Trade with peoples to the southwest brought the bow and arrow[9] An increase in the hierarchical structuring of their societies began during this period, although it is not clear whether it was internally developed or borrowed from the Hopewell. The dead were treated in increasingly elaborate ways, as the first burial mounds are built at this time.[8] Political power begins to be consolidated; the first platform mounds and ritual centers were constructed as part of the development of a hereditary political and religious leadership.[8]

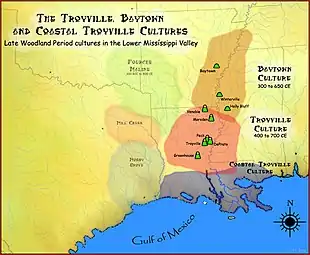

By 400 AD in the eastern part of the state, the Late Woodland period had begun with the Baytown and Troyville cultures (named for the Troyville Earthworks in Jonesville, Louisiana), and later the Coles Creek culture. Archaeologists have traditionally viewed the Late Woodland as a time of cultural decline after the florescence of the Hopewell peoples. Late Woodland sites, with the exception of sites along the Florida Gulf Coast, tend to be small when compared with Middle Woodland sites. Although settlement size was small, there was an increase in the number of Late Woodland sites over Middle Woodland sites, indicating a population increase. These factors tend to mark the Late Woodland period as an expansive period, not one of a cultural collapse.[10] Where the Baytown peoples began to build more dispersed settlements, the Troyville people instead continued building major earthwork centers.[11] The type site for the culture, the Troyville Earthworks, once had the second tallest precolumbian mound in North America and the tallest in Louisiana at 82 feet (25 m) in height.[12]

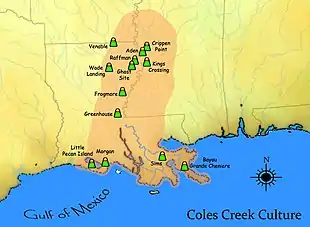

The Coles Creek culture from 700 to 1200 AD marks a significant change in the cultural history of the area. Population increased dramatically, and there is strong evidence of a growing cultural and political complexity, especially by the end of the Coles Creek sequence. Although many of the classic traits of chiefdom societies are not yet manifested, by 1000 CE the formation of simple elite polities had begun. Coles Creek sites are found in present-day Arkansas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Mississippi, and Texas. Many Coles Creek sites were erected over earlier Woodland period mortuary mounds, leading researchers to speculate that emerging elites were symbolically and physically appropriating dead ancestors to emphasize and project their own authority.[13]

Mississippian period

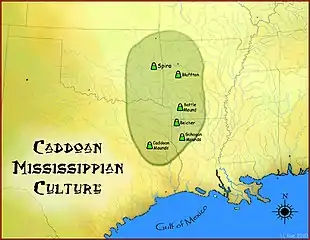

The Mississippian period in Louisiana saw the emergence of the Plaquemine and Caddoan Mississippian cultures. This was the period when extensive maize agriculture was adopted. The Plaquemine culture in the lower Mississippi River Valley in western Mississippi and eastern Louisiana began in 1200 AD and continued until about 1600 AD. Good examples of this culture are the Medora site (the type site for the culture and period), Fitzhugh Mounds, Transylvania Mounds, and Scott Place Mounds in Louisiana and the Anna, Emerald, Winterville and Holly Bluff sites located in Mississippi.[14] Plaquemine culture was contemporaneous with the Middle Mississippian culture at the Cahokia site near St. Louis, Missouri. By 1000 AD in the northwestern part of the state the Fourche Maline culture had evolved into the Caddoan Mississippian culture. By 1400 AD Plaquemine had started to hybridize through contact with Middle Mississippian cultures to the north and became what archaeologist term Plaquemine Mississippian. These peoples are considered ancestral to historic groups encountered by the first Europeans in the area, the Natchez and Taensa peoples.[15] The Caddoan Mississippians covered a large territory, including what is now eastern Oklahoma, western Arkansas, northeast Texas, and northwest Louisiana. Archaeological evidence that the cultural continuity is unbroken from prehistory to the present, and that the direct ancestors of the Caddo and related Caddo language speakers in prehistoric times and at first European contact and the modern Caddo Nation of Oklahoma is unquestioned today.[16] Significant Caddoan Mississippian archaeological sites in Louisiana include Belcher Mound Site in Caddo Parish[17] and Gahagan Mounds Site in Red River Parish.[18]

Native groups at time of European settlement

The following groups are known to have inhabited the state's territory when the Europeans began colonization:[19]

- The Choctaw nation (Muskogean):

- The Bayougoula, in areas directly north of the Chitimachas in the parishes of St. Helena, Tangipahoa, Washington, East Baton Rouge, West Baton Rouge, Livingston, and St. Tammany. They were allied with the Quinipissa-Mougoulacha in St. Tammany parish.

- The Houma in the East and West Feliciana and Pointe Coupee parishes (about 100 miles (160 km) north of the town named for them).

- The Okelousa in Pointe Coupee parish.

- The Acolapissa in St. Tammany parish. They were allied with the Tangipahoa in Tangipahoa parish.

- The Natchez nation:

- The Caddo Confederacy:

- The Adai in Natchitoches parish

- The Natchitoches confederacy consisting of the Natchitoches in Natchitoches parish

- The Yatasi and Nakasa in the Caddo and Bossier parishes,

- The Doustioni in Natchitoches parish, and Ouachita in the Caldwell parish.

- The Atakapa in southwestern Louisiana in Vermilion, Cameron, Lafayette, Acadia, Jefferson Davis, and Calcasieu parishes. They were allied with the Appalousa in St. Landry parish.

- The Chitimacha in the southeastern parishes of Iberia, Assumption, St. Mary, lower St. Martin, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. James, St. John the Baptist, St. Charles, Jefferson, Orleans, St. Bernard, and Plaquemines. They were allied with the Washa in Assumption parish, the Chawasha in Terrebonne parish, and the Yagenechito to the east.

- The Tunica in northeastern parishes of Tensas, Madison, East Carroll and West Carroll, and the related Koroa in East Carroll parish.

Many current place names in the state, including Atchafalaya, Natchitouches (now spelled Natchitoches), Caddo, Houma, Tangipahoa, and Avoyel (as Avoyelles), are transliterations of those used in various Native American languages.

European contact

The first European explorers to visit Louisiana came in 1528 when a Spanish expedition led by Panfilo de Narváez located the mouth of the Mississippi River. In 1542, Hernando de Soto's expedition skirted to the north and west of the state (encountering Caddo and Tunica groups) and then followed the Mississippi River down to the Gulf of Mexico in 1543. The expedition encountered hostile tribes all along river. Natives followed the boats in large canoes, shooting arrows at the soldiers for days on end as they drifted through their territory. The Spanish, whose crossbows had long ceased working, had no effective offensive weapons on the water and were forced to rely on their remaining armor and sleeping mats to block the arrows. About 11 Spaniards were killed along this stretch and many more wounded. Neither of the explorations made any claims to the territory for Spain.

French exploration and colonization (1682–1763)

European interest in Louisiana was dormant until the late 17th century, when French expeditions, which had imperial, religious and commercial aims, established a foothold on the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast. With its first settlements, France lay claim to a vast region of North America and set out to establish a commercial empire and French nation stretching from the Gulf of Mexico through Canada. It was also establishing settlements in Canada, from the Maritimes westward along the St. Lawrence River and into the region surrounding the Great Lakes.

The French explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle named the region Louisiana in 1682 to honor France's King Louis XIV. The first permanent settlement, Fort Maurepas (at what is now Ocean Springs, Mississippi, near Biloxi), was founded in 1699 by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, a French military officer from Canada.

French leaders encouraged French men to marry French women while in Louisiana, and specifically not Native Americans, for "the purpose of a more respectable and successful colony." However, clergy members encouraged French men to marry their Indian sexual partners to avoid sin, as well as convert to Christianity. Some French men would also purchase women as slaves for a brief period for "domestic chores in the woods."[20][21]

The French colony of Louisiana originally claimed all the land on both sides of the Mississippi River and north to French territory in Canada around the Great Lakes. A royal ordinance of 1722—following the transfer of the Illinois Country's governance from Canada to Louisiana—may have featured the broadest definition of the region: all land claimed by France south of the Great Lakes between the Rocky Mountains and the Alleghenies[22]

A generation later, trade conflicts between Canada and Louisiana led to a more defined boundary between the French colonies; in 1745, Louisiana governor general Vaudreuil set the northern and eastern bounds of his domain as the Wabash valley up to the mouth of the Vermilion River (near present-day Danville, Illinois); from there, northwest to le Rocher on the Illinois River, and from there west to the mouth of the Rock River (at present day Rock Island, Illinois).[22] Thus, Vincennes and Peoria were the limit of Louisiana's reach; the outposts at Ouiatenon (on the upper Wabash near present-day Lafayette, Indiana), Chicago, Fort Miamis (near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana) and Prairie du Chien operated as dependencies of Canada.[22]

This boundary between Canada and Louisiana remained in effect until the Treaty of Paris in 1763, after which France ceded its remaining claims east of the Mississippi—except for New Orleans—to Great Britain. (Although British forces had established control over the "Canadian" posts in the Illinois and Wabash countries in 1761, they did not have control over Vincennes or the Mississippi River settlements at Cahokia and Kaskaskia until 1764, after the ratification of the peace treaty.[23]) As part of a general report on conditions in the newly conquered lands, Gen. Thomas Gage, then commandant at Montreal, explained in 1762 that, although the boundary between Louisiana and Canada wasn't exact, it was understood the upper Mississippi above the mouth of the Illinois was in Canadian trading territory.[24] The French established an important and lucrative fur trade in the northern areas, which became increasingly important. It competed with Dutch, and later English merchants, across the northern tier for fur trade with the Native Americans. The fur trade also helped cement alliances between Europeans and Native American tribes.

The settlement of Natchitoches (along the Red River in present-day northwest Louisiana) was established in 1714 by Louis Juchereau de St. Denis, making it the oldest permanent settlement in the territory that then composed the Louisiana colony. The French settlement had two purposes: to establish trade with the Spanish in Texas via the Old San Antonio Road (sometimes called El Camino Real, or Kings Highway)—which ended at Nachitoches—and to deter Spanish advances into Louisiana. The settlement soon became a flourishing river port and crossroads. Sugar cane plantations were developed first. In the nineteenth century, cotton plantations were developed along the river. Over time, planters developed large plantations but also lived in fine homes in a growing town, a pattern repeated in New Orleans and other places.

Louisiana's French settlements contributed to further exploration and outposts. They were concentrated along the banks of the Mississippi and its major tributaries, from Louisiana to as far north as the region called the Illinois Country, in modern-day Indiana, Illinois and Missouri.

Initially Mobile, and (briefly) Biloxi served the capital of the colony. In 1722, recognizing the importance of the Mississippi River to trade and military interests, France made New Orleans the seat of civilian and military authority. The Illinois Country exported its grain surpluses down the Mississippi to New Orleans, which climate could not support their cultivation. The lower country of Louisiana (modern-day Arkansas, Mississippi and Louisiana) depended on the Illinois French for survival through much of the eighteenth century.

European settlement in the Louisiana colony was not exclusively French; in the 1720s, German immigrants settled along the Mississippi River in a region referred to as the German Coast.

Africans and early slavery

In 1719, two French ships arrived in New Orleans, the Duc du Maine and the Aurore, carrying the first African slaves to Louisiana for labor.[25][26] From 1718 to 1750, traders transported thousands of captive Africans to Louisiana from the Senegambian coast, the west African region of the interior of modern Benin, and from the coast of modern Democratic Republic of the Congo-Angola border. French shipping records, in contrast to those of other European nations, contained extensive details of the origins of enslaved Africans taken onboard slave ships. Researchers have found that approximately 2,000 persons originated from the upper West African slave ports from Saint-Louis, Senegal to Cap Appolonia (present-day Ébrié Lagoon, Côte d'Ivoire) several hundred kilometers to the south; an additional 2,000 were exported from the port of Whydah (modern Ouidah, Benin); and roughly 300 departed from Cabinda.[27]

Gwendolyn Midlo Hall has argued that, due to historical and administrative ties between France and Senegal, "Two-thirds of the slaves brought to Louisiana by the French slave trade came from Senegambia."[28] This assertion is not universally accepted. This region between the Senegal and Gambia rivers had peoples who were closely related through history: three of the principal languages, Sereer, Wolof and Pulaar were related, and Malinke, spoken by the Mande people to the east, was "mutually intelligible" with them. Hall thinks that this concentration of peoples from one region of Africa helped shape the Creole culture in Louisiana.[28]

Peter Caron says that the geographic and perhaps linguistic connection among many African captives did not necessarily imply developing a common culture in Louisiana. They likely differed in religions. Some slaves from Senegambia were Muslims while most followed their traditional spiritual practices. Many were likely captives taken in the Islamic jihads that engulfed the region from Futa Djallon to Futa Toro and Futa Bundu (modern Upper Niger River) in the early 18th century.[27] The inland territories of the African continent from which slaves were captured, were enormous. Commentators may have attributed more similarities to slaves taken from among these areas than the Africans recognized among themselves at the time.[29]

Spanish interregnum (1763–1803)

.png.webp)

France ceded most of its territory east of the Mississippi to the Kingdom of Great Britain after its defeat in the Seven Years' War. The area around New Orleans and the parishes around Lake Pontchartrain, along with the rest of Louisiana, became a possession of Spain after the Seven Years' War by the Treaty of Paris of 1763.

Spanish rule did not affect the pace of francophone immigration to the territory, which increased due to the expulsion of the Acadians. Several thousand French-speaking refugees from Acadia (now Nova Scotia, Canada) migrated to colonial Louisiana. The first group of around 200 arrived in 1765, led by Joseph Broussard (also referrerd to as "Beausoleil").[30] They settled chiefly in the southwestern Louisiana region now called Acadiana. The Acadian refugees were welcomed by the Spanish as additions of Catholic population. Their white descendants came to be called Cajuns and their black descendants, mixed with African ancestry came to be called Creole. Additionally, many Cajun and Creole Louisianians share Native American and/or Spanish ancestry.

In 1779 during the American Revolutionary War, New Orleans Governor Bernardo de Galvez successfully led Spanish, New Orleans French, and Acadian/Cajun troops against the English in several victorious battles, including Baton Rouge.

During this time, Spanish-speaking immigrants arrived such as the Canary Islanders of Spain, which are known as the Isleños and Andalusians from the south of Spain called Malagueños. The Isleños and Malagueños immigrated to Louisiana between 1778 and 1783. The Isleños settled in southeast Louisiana mainly in St. Bernard Parish, just outside of New Orleans, as well as near the area just below Baton Rouge. The Malagueños settled mainly around New Iberia, but some spread to other parts of southern Louisiana.

Both free and enslaved populations increased rapidly during the years of Spanish rule, as new settlers and Creoles imported large numbers of slaves to work on plantations. Although some American settlers brought slaves with them who were native to Virginia or North Carolina, the Pointe Coupee inventories of the late eighteenth century showed that most slaves brought by traders came directly from Africa. In 1763 settlements from New Orleans to Pointe Coupee (north of Baton Rouge) included 3,654 free persons and 4,598 slaves. By the 1800 census, which included West Florida, there were 19,852 free persons and 24,264 slaves in Lower Louisiana. Although the censuses do not always cover the same territory, the slaves became the majority of the population during these years. Records during Spanish rule were not as well documented as with the French slave trade, making it difficult to trace African origins. The volume of slaves imported from Africa resulted in what historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall called "the re-Africanization" of Lower Louisiana, which strongly influenced the culture.[31]

In 1800, France's Napoleon Bonaparte reacquired Louisiana from Spain in the Treaty of San Ildefonso, an arrangement kept secret for some two years. Documents have revealed that he harbored secret ambitions to reconstruct a large colonial empire in the Americas. This notion faltered, however, after the French attempt to reconquer Saint-Domingue after its revolution ended in failure, with the loss of two-thirds of the more than 20,000 troops sent to the island to suppress the revolution. After French withdrawal in 1803, Haiti declared its independence in 1804 as the second republic in the Western Hemisphere.

Incorporation into the United States and antebellum years (1803–1860)

As a result of his setbacks, Napoleon gave up his dreams of American empire and sold Louisiana (New France) to the United States. The U.S. divided the land into two territories: the Territory of Orleans, which became the state of Louisiana in 1812, and the District of Louisiana, which consisted of the vast lands not included in the Orleans Territory, extending west of the Mississippi River north to Canada. The Florida Parishes were annexed from the short-lived and strategically important Republic of West Florida, by proclamation of President James Madison in 1810.

The Haitian Revolution (1791–1804) resulted in a major emigration of refugees to Louisiana, where they settled chiefly in New Orleans. Thousands of Saint Dominican refugees arrived to Louisiana, which included Creoles of color, white Creoles, and slaves. Some refugees had earlier gone to Cuba, and were expelled from Cuba in another wave of immigration in 1809. The Saint Dominicans increased the Creole community of New Orleans substantionally, enlarging the French-speaking community.[32]

In 1811, the largest slave revolt in American history, the German Coast Uprising, took place in the Orleans Territory. Between 64 and 500 slaves rose up on the "German Coast," forty miles upriver of New Orleans, and marched to within 20 miles (32 km) of the city gates. All of the limited number of U.S. troops were gathered to suppress the revolt, as well as citizen militias.

U.S. statehood

Louisiana became a U.S. state on April 30, 1812. The western boundary of Louisiana with Spanish Texas remained in dispute until the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, which was formally ratified in 1821,[33] The area referred to as the Sabine Free State served as a neutral buffer zone.

With the growth of settlement in the Midwest (formerly the Northwest Territory) and Deep South during the early decades of the 19th century, trade and shipping increased markedly in New Orleans. Produce and products moved out of the Midwest down the Mississippi River for shipment overseas, and international ships docked at New Orleans with imports to send into the interior. The port was crowded with steamboats, flatboats, and sailing ships, and workers speaking languages from many nations. New Orleans was the major port for the export of cotton and sugar. The city's population grew and the region became quite wealthy. More than the rest of the Deep South, it attracted immigrants for the many jobs in the city. The richest citizens imported fine goods of wine, furnishings, and fabrics.

By 1840 New Orleans had the biggest slave market in the United States, which contributed greatly to the economy. It had become one of the wealthiest cities and the third-largest city in the nation.[34] The ban on importation of slaves had increased demand in the domestic market. During these decades after the American Revolutionary War, more than one million enslaved African Americans underwent forced migration from the Upper South to the Deep South, two thirds of them in the slave trade. Others were transported by slaveholders as they moved west for new lands.[35][36]

With changing agriculture in the Upper South as planters shifted from tobacco to less labor-intensive mixed agriculture, planters had excess laborers. Many sold slaves to traders to take to the Deep South. Slaves were driven by traders overland from the Upper South or transported to New Orleans and other coastal markets by ship in the coastwise slave trade. After sales in New Orleans, steamboats operating on the Mississippi transported slaves upstream to markets or plantation destinations at Natchez and Memphis.

Secession and the American Civil War (1860–1865)

.svg.png.webp)

With its plantation economy, Louisiana was a state that generated wealth from the labor of and trade in enslaved Africans. It also had one of the largest free black populations in the United States, totaling 18,647 people in 1860. Most of the free blacks (or free people of color, as they were called in the French tradition) lived in the New Orleans region and southern part of the state. More than in other areas of the South, most of the free people of color were of mixed race. Many gens de couleur libre in New Orleans were middle class and educated; many were also property owners. In contrast, according to the 1860 census, 331,726 people were enslaved, nearly 47% of the state's total population of 708,002.[37]

Construction and elaboration of the levee system was critical to the state's ability to cultivate its commodity crops of cotton and sugar cane. Enslaved Africans built the first levees under planter direction. Later levees were expanded, heightened and added to mostly by Irish immigrant laborers, whom contractors hired when doing work for the state. As the 19th century progressed, the state had an interest in ensuring levee construction. By 1860, Louisiana had built 740 miles (1,190 km) of levees on the Mississippi River and another 450 miles (720 km) of levees on its outlets. These immense earthworks were built mostly by hand. They averaged six feet in height, and up to twenty feet in some areas.[38]

Enfranchised elite whites' strong economic interest in maintaining the slave system contributed to Louisiana's decision to secede from the Union in 1861. It followed other Southern states in seceding after the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States. Louisiana's secession was announced on January 26, 1861, and it became part of the Confederate States of America.

The state was quickly overtaken by Union troops in the American Civil War, a result of Union strategy to cut the Confederacy in two by seizing the Mississippi. Federal troops captured New Orleans on April 25, 1862. Due to a large enough portion of Louisiana's population being Southern Unionist and having Unionist leanings, (or compatible commercial interests), the Federal government took the unusual step of designating the areas of Louisiana under Federal control as a state within the Union, with its own elected representatives to the U.S. Congress.

Late 19th to early 20th century

Reconstruction, disenfranchisement, and segregation (1865–1929)

In the immediate aftermath of the American Civil War, many Confederates regained public office. Legislature across the South passed Black Codes that restricted the rights of freedmen, such as the right to travel, and forced them to sign year-long contracts with planters. Anyone without proof of a contract by the start of the year was considered a vagrant and could be arrested, imprisoned, and leased out to work through the convict leasing system that discriminated against Blacks. With the passage of the Reconstruction Acts, Congress took control of Reconstruction and the South, excluding Tennessee, was placed under the supervision of military governors under congressional control. Louisiana was grouped with Texas in what was administered as the Fifth Military District. Congress dictated that for reentry into the Union, the late rebel state would have to ratify the 14th Amendment and pass new constitutions that enfranchised the freedmen. Louisiana's 1868 Constitution abolished the Black Codes, granted full civil and political equality to freedmen, disenfranchised several classes of ex-Confederates, and included the state's first formal bill of rights. African Americans began to live as citizens with some measure of equality before the law. Both freedmen and people of color who had been free before the war began to make more advances in education, family stability and jobs. At the same time, there was tremendous social volatility in the aftermath of war, with many whites actively resisting defeat. White insurgents mobilized to enforce white supremacy, first in Ku Klux Klan chapters.

According to Barry Crouch, George Ruby, a mulatto from New England was a leader in black education in Louisiana from 1863 to 1866. The Army assigned Ruby to the Freedmen's Bureau. His roles encompassed that of a teacher, a school administrator, and a mobile inspector for the Bureau. His responsibilities included assessing local conditions, assisting in the establishment of black schools, and evaluating the performance of Bureau field officers. Ruby's endeavors were met with a positive response from the black population, who eagerly embraced education, but they also faced vehement opposition, including physical violence, from numerous planters and other white individuals. Ruby's career exemplifies the role played by the Black carpetbagger during the Civil War and Reconstruction era in Louisiana.[39]

In the 1870s, whites accelerated their insurgency to regain control of political power in the state. The Red River area, where new parishes had been created by the Reconstruction legislature, was an area of conflict. On Easter Sunday 1873, an estimated 85 to more than 100 blacks were killed in the Colfax massacre, as white militias had gathered to challenge Republican officeholders after the disputed gubernatorial election of 1872.

Paramilitary groups such as the White League, formed in 1874, used violence and outright assassination to turn Republicans out of office, and intimidate African Americans and suppress black voting, control their work, and limit geographic movement in an effort to control labor. Among violent acts attributed to the White League in 1874 was the Coushatta massacre, where they killed six Republican officeholders, including four family members of the local state senator, and twenty freedmen as witnesses.[40]

Later, 5,000 White Leaguers battled 3,500 members of the Metropolitan Police and state militia in New Orleans after demanding the resignation of Governor William Pitt Kellogg. They hoped to replace him with the Democratic candidate of the disputed 1872 elections, John McEnery. The White League briefly took over the statehouse and city hall before Federal troops arrived.[41] In 1876, the white Democrats regained control of Louisiana.

Through the 1880s, white Democrats began to reduce voter registration of blacks and poor whites by making registration and elections more complicated. They imposed institutionalized forms of racial discrimination and also conducted voter intimidation and violence against black Republicans. The rate of lynchings of blacks increased through the century, reaching a peak in the late 1800s, but with lynchings continuing well into the 20th century. Blacks came out in force in the April 1896 elections, in areas where they could freely vote, to support a Republican-Populist fusion ticket that might overturn the conservative Democrats. Blacks were threatened by increasing talk about restricting their vote, and Mississippi had already passed a new constitution in 1890 that disenfranchised most blacks. Racial tensions and violence were high, and there were 21 lynchings of blacks in Louisiana that year, surpassing the total for any state. Returns from Democratic-controlled plantation parishes were doctored, and the Democrats won the race. The legislature "refused to investigate what everyone knew was a stolen election."[42]

In 1898, the white Democratic, planter-dominated legislature passed a new disenfranchising constitution, with provisions for voter registration, such as poll taxes, residency requirements and literacy tests, to raise barriers to black voter registration, as Mississippi had successfully done. The effect was immediate and long lasting. In 1896, there were 130,334 black voters on the rolls and about the same number of white voters, in proportion to the state population, which was evenly divided.[43]

The state population in 1900 was 47% African-American: 652,013 citizens, of whom many in New Orleans were descendants of Creoles of color, the sizable population of blacks free before the American Civil War.[44] By 1900, two years after the new constitution, only 5,320 black voters were registered in the state. Because of disenfranchisement, by 1910 there were only 730 black voters (less than 0.5 percent of eligible African-American men), despite advances in education and literacy among blacks and people of color.[45] White Democrats had established one-party rule, which they maintained in the state for decades deep into the 20th century until after the 1965 Voting Rights Act provided federal enforcement of the constitutional right to vote.

In the notable 19th-century U.S. Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities were constitutional. The lawsuit, based on restricted seating in interstate passenger trains, was brought from Louisiana with strong support from the Creoles of color community in New Orleans: Plessy was one. Separation through segregation, however, resulted everywhere in lesser services and facilities for blacks.

From July 24–27, 1900, New Orleans erupted in a white race riot after Robert Charles, an African-American laborer, fatally shot a white police officer during an altercation. He escaped and during and after the manhunt for him, whites rampaged through the city attacking other blacks and burning down two black schools. A total of 28 people died, including Charles, and more than 50 were wounded. Most of the casualties were black. The riot received national attention and ended only with intervention by state militia.[46]

As a result of disfranchisement, African Americans in Louisiana essentially had no representation; as they could not vote, they could not participate in juries or in local, state or federal offices. As a result, they suffered inadequate funding for schools and services, and lack of attention to their interests and worse in the segregated state. They continued to build their own lives and institutions.

In 1915, the Supreme Court struck down the grandfather clause in its ruling in Guinn v. United States. Although the case originated in Oklahoma, Louisiana and other Southern states had used similar clauses to exempt white voters from literacy tests. State legislators quickly passed new requirements for potential voters to demonstrate "understanding," or reading comprehension, to official registrars. Administered subjectively by whites, in practice the understanding test was used to keep most black voters off the rolls. By 1923, Louisiana established the all-white primary, which effectively shut out the few black voters from the Democratic Party, the only competitive part of elections in the one-party state.[47]

In the middle decades of the 20th century, thousands of African Americans left Louisiana in the Great Migration north to industrial cities. The boll weevil infestation and agricultural problems had cost sharecroppers and farmers their jobs, and continuing violence drove out many families. The mechanization of agriculture had reduced the need for many farm laborers. They sought skilled jobs in the burgeoning defense industry in California in the 1940s, better education for their children, and living opportunities in communities where they could vote, as well as an escape from southern violence.[48]

Orphan trains

During some of this period, Louisiana accepted Catholic orphans in an urban resettlement program organized in New York City. Opelousas was a destination for at least three of the Orphan Trains which carried orphan children out of New York from 1854 to 1929. It was the heart of a traditional Catholic region of French, Spanish, Acadian, African and French West Indian heritage and traditions. Families in Louisiana took in more than 2,000 mostly Catholic orphans to live in rural farming communities. The city of Opelousas is constructing an Orphan Train Museum (second in the nation) in an old train depot located in Le Vieux Village in Opelousas. The first museum dedicated to the Orphan Train children is located in Kansas.

Mid-to-late 20th century

Great Depression and World War II (1929–1940s)

During some of the Great Depression, Louisiana was led by Governor Huey Long. He was elected to office on populist appeal. Though popular for his public works projects, which provided thousands of jobs to people in need, and for his programs in education and increased suffrage for poor whites, Long was criticized for his allegedly demagogic and autocratic style. He extended patronage control through every branch of Louisiana's state government. Especially controversial were his plans for wealth redistribution in the state. Long's rule ended abruptly with his assassination in the state capitol in 1935.

Mobilization for World War II created defense industry jobs in the state, attracting thousands of rural black and white farmers into the cities to obtain such employment. However, tens of thousands of black workers left the state in the Second Great Migration for the North and West Coast to seek skilled jobs and better pay in the defense industry outside the South, better education for themselves and their children, and living opportunities in communities where they could vote.[49]

Although Long removed the poll tax associated with voting, the all-white primaries were maintained through 1944, until the Supreme Court struck them down in Smith v. Allwright. Through 1948 black people in Louisiana continued to be essentially disfranchised, with only 1% of those eligible managing to vote.[50] Schools and public facilities continued to be segregated.

Civil Rights movement (1950–1970)

State legislators created other ways to suppress black voting, but from 1948 to 1952, it crept up to 5% of those eligible. Civil rights organizations in New Orleans and southern parishes, where there had been a long tradition of free people of color before the American Civil War, worked hard to register black voters.

In the 1950s the state created new requirements for a citizenship test for voter registration. Despite opposition by the States' Rights Party, downstate black voters began to increase their rate of registration, which also reflected the growth of their middle classes. Gradually black voter registration and turnout increased to 20% and more, but it was still only 32% by 1964, when the first civil rights legislation of the era was passed.[51] The percentage of black voters ranged widely in the state during these years, from 93.8% in Evangeline Parish to only 1.7% in Tensas Parish, for instance.[52]

Patterns of Jim Crow segregation against African Americans still ruled in Louisiana in the 1960s. Because of the Great Migration of blacks to the north and west, and growth of other groups in the state, by 1960 the proportion of African Americans in Louisiana had dropped to 32%. The 1,039,207 black citizens were adversely affected by segregation and efforts at disfranchisement.[53] African Americans continued to suffer disproportionate discriminatory application of the state's voter registration rules. Because of better opportunities elsewhere, from 1965 to 1970, blacks continued to migrate from Louisiana, for a net loss of more than 37,000 people. During the latter period, some people began to migrate to cities of the New South for opportunities.[54]

The disfranchisement of African Americans did not end until their leadership and activism throughout the South during the Civil Rights movement gained national attention and Congressional action. This led to securing passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, with President Lyndon Johnson's leadership as well. By 1968 almost 59% of eligible-age African Americans had registered to vote in Louisiana. Contemporary rates for African-American voter registration and turnout in the state are above 70%, demonstrating the value they give it, a higher rate of participation than for African-American voters outside the South.[52]

21st century

Since colonization, the American Civil War, and the Civil Rights movement, Louisiana during the 21st century began transitioning to a more racially and ethnically diverse state; the state also became a center for the film industry and growing technology firms from North Louisiana to Acadiana.[55][56][57][58] As Southern Louisiana grew in population during the beginning of the 21st century, more significant concern was expressed for climate change and sea level rise.[59][60]

Hurricane Katrina

In August 2005, New Orleans and many other low-lying parts of the state along the Gulf of Mexico were hit by the catastrophic Hurricane Katrina. It caused widespread damage due to the breaching of levees and large-scale flooding of more than 80% of the city. Officials issued warnings to evacuate the city and nearby areas, but tens of thousands of people, mostly African Americans, had stayed behind, some stranded, and suffered through the damage of the widespread flood waters.

Cut off in many cases from healthy food, medicine, or water, or assembled in public spaces without functioning emergency services, more than 1,500 people in New Orleans died in the aftermath. Government at all levels had failed to prepare adequately despite severe hurricane warnings, and emergency responses were slow. The state faced a humanitarian crisis stemming from conditions in many locations and the large tide of evacuating citizens, especially the city of New Orleans.

Early 2010s

In 2010, Baton Rouge started a market push to become a test city for Google's new super high speed fiber optic line known as GeauxFiBR.[61]

Mid to late 2010s

In 2015, the city of Lafayette gained international attention for a mass shooting and murder-suicide at Grand 16 Theater;[62][63] this mass shooting spurred further discussion and debate on gun control in the United States.[64] During 2015, the Lafayette metropolitan area also overtook the Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area by population, becoming Louisiana's third largest metropolitan region.[65]

In July 2016 the shooting of Alton Sterling sparked protests throughout the state capital of Baton Rouge.[66][67] In August 2016, an unnamed storm dumped trillions of gallons of rain on southern Louisiana, including the cities of Denham Springs, Baton Rouge, Gonzales, St. Amant and Lafayette, causing catastrophic flooding.[68] An estimated 110,000 homes were damaged and thousands of residents were displaced.[69][70]

In 2016, the Greater Baton Rouge metropolitan area was heavily affected by the shooting of police officers in July and flooding in August.

In 2019, three Louisiana black churches were set on fire.[71] The suspect used gasoline, destroying each church completely. Holden Matthews, 21 years old, was charged with the destruction of the churches.[72][73]

Early 2020s

The first presumptive case relating to the COVID-19 pandemic in Louisiana was announced on March 9, 2020. Since the first confirmed case, the outbreak grew particularly fast relative to other states and countries. Confirmed cases have appeared in all 64 parishes, though the New Orleans metro area alone has seen the majority of positive tests and deaths. Governor John Bel Edwards closed schools statewide on March 16, 2020, restricted most businesses to takeout and delivery only, postponed presidential primaries, and placed limitations on large gatherings.[74][75] On March 23, Edwards enacted a statewide stay-at-home order to encourage social distancing, and President Donald Trump issued a major disaster declaration, the fourth state to receive one.[74][76]

The rapid spread of COVID-19 in Louisiana likely originated in late February 2020 when the virus was introduced into the state via domestic travel, originating from a single source.[77] The virus was already present in New Orleans before Mardi Gras; however, it is likely that the festival accelerated the spread.[77]

Numerous "clusters" of confirmed cases have appeared at nursing homes across southern Louisiana, including an outbreak at Lambeth House in New Orleans that has infected over fifty and killed thirteen elderly residents as of March 30.[78][79] As the state has increased its capacity for testing, a University of Louisiana at Lafayette study estimated the growth rate in Louisiana was among the highest in the world, prompting serious concerns about the state's healthcare capacity to care for sick patients. On March 24, only 29% of ICU beds were vacant statewide, and Edwards announced coronavirus patients would likely overwhelm hospitals in New Orleans by April 4.[80]

As of May 28, 2021, Louisiana has administered 3,058,019 COVID-19 vaccine doses, and has fully vaccinated 1,337,323 people, equivalent to 28.67 percent of the population.[81] As of November 19, 2021, the number of doses administered has reached 5,096,864, and the number of fully vaccinated individuals is 2,253,496, representing 48.31 percent of the population.[82]

On August 29, 2021, Hurricane Ida made landfall in Louisiana, passing through New Orleans on the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina. A citywide power outage and significant damage was reported.[83] The post-Katrina levee system successfully defended the city, but some suburbs without levees or where levees were still under construction flooded.[84]

See also

References

- ↑ Reonas, Matthew. Great Depression in Louisiana. 64parishes.org. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ↑ Sanson, P. Jerry. World War II – 64 Parishes. 64parishes.org. Retrieved January 27, 2022.

- ↑ Louisiana: | Infoplease. Retrieved March 17, 2022.

- ↑ Amélie A. Walker, "Earliest Mound Site", Archaeology Magazine, Volume 51 Number 1,

- ↑ Jon L. Gibson, PhD, "Poverty Point: The First Complex Mississippi Culture" Archived December 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, 2001, Delta Blues, accessed October 26, 2009

- ↑ "The Tchefuncte Site Summary" (PDF). Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ↑ "Louisiana Prehistory-Marksville, Troyville-Coles Creek, and Caddo". Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Tejas-Caddo Ancestors-Woodland Cultures". Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ↑ "OAS-Oklahomas Past". Archived from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved February 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Southeastern Prehistory-Late Woodland Period". Retrieved September 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Southeastern Prehistory : Late Woodland Period". NPS.GOV. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Indian Mounds of Northeast Louisiana: Transylvania Mounds". Archived from the original on March 20, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ↑ Kidder, Tristram (1998). R. Barry Lewis; Charles Stout (eds.). Mississippian Towns and Sacred Spaces. University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-0947-0.

- ↑ "Mississippian and Late Prehistoric Period". Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ↑ "The Plaquemine Culture, A.D 1000". Retrieved September 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Tejas-Caddo Fundamentals-Caddoan Languages and Peoples". Retrieved February 4, 2010.

- ↑ "Historical-Belcher". Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Notice of Inventory Completion for Native American Human Remains and Associated Funerary Objects in the Possession of the Louisiana State University Museum". Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ↑ Sturdevent, William C. (1967): Early Indian Tribes, Cultures, and Linguistic Stocks, Smithsonian Institution Map (Eastern United States).

- ↑ Reis, Elizabeth, ed. (2012). American sexual histories. Blackwell readers in American social and cultural history (2nd ed.). Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-3929-1.

- ↑ Spear, Jennifer M. (2009). Race, sex, and social order in early New Orleans. Early America. Baltimore (Md.): The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-8680-5.

- 1 2 3 Ekberg, Carl (2000). French Roots in the Illinois Country: The Mississippi Frontier in Colonial Times. Urbana and Chicago, Ill.: University of Illinois Press. pp. 32–33. ISBN 9780252069246. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ↑ Hamelle, W.H. (1915). A Standard History of White County, Indiana. Chicago and New York: Lewis Publishing Co. p. 12. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ↑ Shortt, Adam; Doughty, Arthur G., eds. (1907). Documents Relating to the Constitutional History of Canada, 1759–1791. Ottawa: Public Archives Canada. p. 72. Retrieved November 29, 2014.

- ↑ Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (1995). Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8071-1999-0.

- ↑ "theusgenweb.org "Immigrants to Colonial Louisiana"". Archived from the original on January 31, 2009.

- 1 2 Caron, Peter (April 1997). "'Of a nation the others do not understand': Bambara Slaves and African Ethnicity in Colonial Louisiana, 1718–60". Slavery & Abolition. 18 (1): 98–121. doi:10.1080/01440399708575205. 0144-039X.

- 1 2 Hall 1995, p. 29.

- ↑ For a general discussion of these topics see, Eltis, David; Richardson, David, eds. (1997). Routes to Slavery: Directions, Ethnicity and Mortality in the Atlantic Slave Trade. London: Frank Cass & Co Ltd. ISBN 0-7146-4820-5.

- ↑ "www.carencrohighschool.org "Broussard named for early settler Valsin Broussard"". Archived from the original on May 21, 2009.

- ↑ Hall 1995, p. 279.

- ↑ "Haitian Immigration: 18th & 19th Centuries, The Black Republic and Louisiana", In Motion: African American Migration Experience, New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Study of Black Culture, 2002, accessed May 7, 2008

- ↑ "Adams-Onís Treaty Map". thomaslegioncherokee.tripod.com.

- ↑ Walter Johnson, Soul by Soul: Life Inside the Antebellum Slave Market, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999, p.2

- ↑ In Motion: The African-American Migration Experience- The Domestic Slave Trade, New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Study of Black Culture, 2002 Archived November 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 27, 2008

- ↑ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619–1877, New York: Hill and Wang, 1994, pp.96–98

- ↑ Historical Census Browser, 1860 US Census, University of Virginia, accessed October 31, 2007

- ↑ "Louisiana: The Levee System of the State", The New York Times, October 8, 1874, accessed November 13, 2007

- ↑ Barry A. Crouch, "Black Education in Civil War and Reconstruction Louisiana: George T. Ruby, the Army, and the Freedmen's Bureau." Louisiana History 38.3 (1997): 287–308. online

- ↑ Danielle Alexander, "Forty Acres and a Mule: The Ruined Hope of Reconstruction", Humanities, January/February 2004, Vol.25/No.1. Archived September 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 14, 2008

- ↑ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006, p.76-77.

- ↑ William Ivy Hair, Carnival of Fury: Robert Charles and the New Orleans Race Riot of 1900, LSU Press, 2008, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Pildes, Richard H. (July 13, 2000). "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon". Constitutional Commentary. doi:10.2139/ssrn.224731. hdl:11299/168068. SSRN 224731. Retrieved October 7, 2023 – via Social Science Research Network.

- ↑ Historical Census Browser, 1900 US Census, University of Virginia Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 15, 2008

- ↑ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol. 17, p.12, accessed March 10, 2008

- ↑ William Ivy Hair. Carnival of Fury: Robert Charles and the New Orleans Race Riot of 1900, Louisiana State University Press (1976) ISBN 0-8071-0178-8

- ↑ Debo P. Adegbile, "Voting Rights in Louisiana: 1982–2006", March 2006, pp. 6–7, accessed March 19, 2008 Archived June 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "African American Migration Experience: The Great Migration", In Motion, New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Archived November 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 24, 2008

- ↑ "African American Migration Experience: The Second Great Migration", In Motion, New York Public Library, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture Archived November 4, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, accessed April 24, 2008

- ↑ Debo P. Adegbile, "Voting Rights in Louisiana: 1982–2006", March 2006, p. 7, accessed March 19, 2008 Archived June 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Debo P. Adegbile, Voting Rights in Louisiana: 1982–2006, March 2006, p. 7, accessed March 19, 2008 Archived June 26, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Edward Blum and Abigail Thernstrom, "Executive Summary" Archived April 17, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, Bullock-Gaddie Expert Report on Louisiana, February 10, 2006, p.1, American Enterprise Institute, accessed March 19, 2008

- ↑ Historical Census Browser, 1960 US Census, University of Virginia Archived August 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 15, 2008

- ↑ William H. Frey, "The New Great Migration: Black Americans' Return to the South, 1965–2000"; May 2004, p. 3, The Brookings Institution Archived January 18, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, accessed March 19, 2008

- ↑ Masson, Rob (April 21, 2022). "New Orleans film industry expected to exceed $1 billion in 2022". Fox 8. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ↑ Johnson, Charles (June 2, 2021). "New software developer to bring jobs to Shreveport area". KOKA The Heart of Gospel. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ↑ Daigle, Adam (February 3, 2019). "As the tech industry grows in Acadiana, the race is on both locally and nationally for talent". The Advocate. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ↑ "Louisiana wants more tech jobs. Here's what it can learn from Alabama's tech success". WWNO. January 13, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ↑ Schleifstein, Mark (February 16, 2022). "Seas could rise 2 feet on Louisiana coast by 2050, 4 feet by 2100, federal officials say". NOLA.com. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ↑ "How rising sea levels threaten the lives of Louisiana's coastal residents". PBS NewsHour. April 5, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- ↑ "Groups plan to make push for Google Fiber experiment" Archived July 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine, WAFB, April 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Louisiana cinema shooting: Lafayette gunman 'had violent past'". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. July 24, 2015. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ↑ Shapiro, Emily; Liddy, Tom (July 24, 2015). "Lafayette, Louisiana, Movie Theater Gunman Was 'Intent on Shooting and Escaping'". ABC News. American Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ↑ Crilly, Rob (July 24, 2015). "Two dead in cinema shooting as Obama says he was stymied on gun control". The Telegraph. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ↑ Goff, Jessica. "Lafayette now third largest metro area in the state". The Daily Advertiser. Gannett. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

- ↑ "Alton Sterling protesters treated 'like animals' in Baton Rouge prison, advocacy group claims". The Advocate. July 8, 2017. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ "BRPD officer injured in Alton Sterling protest can pursue negligence claim against organizer". The Advocate. December 17, 2019. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Jason Samenow (August 19, 2016). "No-name storm dumped three times as much rain in Louisiana as Hurricane Katrina". Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

- ↑ Baton Rouge Area Chamber (August 18, 2016). "BRAC's preliminary analysis of potential magnitude of flooding's impact on the Baton Rouge region" (PDF). Baton Rouge Area Chamber. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 16, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2016.

- ↑ Cusick, Ashley (August 16, 2016). "This man bought 108 pounds of brisket to cook for the displaced Baton Rouge victims". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2016.

- ↑ Szekely, Peter (April 11, 2019). "Son of sheriff's deputy charged with burning three Louisiana black churches". Reuters. Archived from the original on September 27, 2020. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Blinder, Alan; Fausset, Richard; Eligon, John (April 11, 2019). "A Charred Gas Can, a Receipt and an Arrest in Fires of 3 Black Churches". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- ↑ Eliott C. McLaughlin (April 15, 2019). "Prosecutor adds hate crimes to charges against Louisiana church fire suspect". CNN. Archived from the original on April 17, 2019. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- 1 2 "Gov. Edwards Issues Statewide Stay at Home Order to Further Fight the Spread of COVID-19 in Louisiana". Louisiana Office of the Governor. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ↑ Corasaniti, Nick; Mazzei, Patricia (March 13, 2020). "Louisiana Postpones April Primary as 4 More States Prepare to Vote on Tuesday". The New York Times. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ↑ Coleman, Justine (March 25, 2020). "Trump approves major disaster declaration in Louisiana for coronavirus pandemic". The Hill. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- 1 2 Zeller, Mark; Gangavarapu, Karthik; Anderson, Catelyn; Smither, Allison R.; Vanchiere, John A.; Rose, Rebecca; Dudas, Gytis; Snyder, Daniel J.; Watts, Alexander; Matteson, Nathaniel L.; Robles-Sikisaka, Refugio (February 8, 2021). "Emergence of an early SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the United States". medRxiv 10.1101/2021.02.05.21251235v1.

- ↑ Umholtz, Katelyn (March 29, 2020). "Coronavirus death toll at Lambeth House in New Orleans at 13; more cases reported". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ↑ Simerman, John (March 29, 2020). "At coronavirus-stricken Lambeth House, halls 'feel like they're full of ghosts' as death toll rises". NOLA.com. Archived from the original on March 29, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ↑ GALLO, ANDREA; SLEDGE, MATT; WOODRUFF, EMILY; KARLIN, SAM (March 24, 2020). "'It's like a war zone': Fighting coronavirus, limited ICU beds, bracing for chaos in New Orleans". NOLA.com. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- ↑ "Louisiana – COVID-19 Overview – Johns Hopkins". Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- ↑ "Louisiana – COVID-19 Overview – Johns Hopkins". Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ↑ Elbaum, Rachel; Ortiz, Erik (August 30, 2021). "Ida weakens to tropical storm after delivering 'catastrophic' damage". NBC News. Retrieved August 30, 2021.

- ↑ New Orleans Levees Passed Hurricane Ida's Test, But Some Suburbs Flooded

Further reading

Surveys

- Allain, Mathe. Louisiana Literature and Literary Figures (2004)

- Baker, Vaughan B. Visions and Revisions: Perspectives on Louisiana Society and Culture (2000)

- Becnel, Thomas A. Agriculture And Economic Development (1997)

- Brasseaux, Carl A. A Refuge for All Ages: Immigration in Louisiana History (1996)

- Gentry, Judith F., and Janet Allured, eds. Louisiana Women: Their Lives and Times. (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009) 354 pp. ISBN 978-0-8203-2947-5

- Kniffen, Fred B.; Hiram F. Gregory; George A. Stokes (1987). The Historic Indian Tribes of Louisiana: From 1542 to the Present. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Louisiana Writers' Project. Louisiana: A Guide to the State. New York: Hastings House, 1941. American Guide Series of the Works Project Administration. Online edition

- Neuman, Robert W.; Lanier A. Simmons (1969). A Bibliography Relative to the Indians of the State of Louisiana. Anthropological Study. Department of Conservation, Louisiana Geological Survey.

- Nolan, Charles. Religion in Louisiana (2004)

- Schafer, Judith K., Warren M. Billings, and Glenn R. Conrad. ''An Uncommon Experience : Law and Judicial Institutions in Louisiana 1803–2003 (1997)

- Wade, Michael G. Education in Louisiana (1999)

- Wall, Bennett H.; Rodrigue, John C., eds. (2014). Louisiana: A History (6th ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-118-61929-2. Standard contemporary survey text.

Colonial to 1900

- Conrad, Glenn R. The French Experience in Louisiana (1995)

- Delatte, Carolyn. Antebellum Louisiana, 1830-1860: Life And Labor(2004)

- Din, Gilbert C. The Spanish Presence in Louisiana, 1763–1803 (1996)

- Labbe, Dolores Egger. The Louisiana Purchase and its Aftermath, 1800–1830 (1998)

- Schott Matthew J. Louisiana Politics and the Paradoxes of Reaction and Reform, 1877–1928, (2000)

- Smith, F. Todd. Louisiana and the Gulf South Frontier, 1500–1821 (LSU Press, 2014) 278 pp.

- Vidal, Cecile, ed. Louisiana: Crossroads of the Atlantic World (University of Pennsylvania Press; 2013) 278 pages; essays by scholars on Louisiana in Atlantic history from the late-17th to the mid-19th centuries.

Civil War and reconstruction

- Arnesen, Eric. Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: race, class, and politics, 1863–1923. (Oxford UP, 1991).

- Bergeron, Arthur. The Civil War in Louisiana: Military Activity (2004)

- Blassingame, John W. Black New Orleans 1860–1880 (U of Chicago Press, 1973).

- Capers, Gerald M. Occupied City, New Orleans Under the Federals 1862–1865. (U of Kentucky Press, 1965).

- Crouch, Barry A. "Black Education in Civil War and Reconstruction Louisiana: George T. Ruby, the Army, and the Freedmen’s Bureau." Louisiana History 38#3 (1997), pp. 287–308. online

- Fischer, Roger. The Segregation Struggle in Louisiana, 1862–1877. (University of Illinois Press: 1974) Study of free persons of color in New Orleans who provided leadership in the unsuccessful fight against segregation of schools and public accommodations.

- Hogue, James Keith. Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battles and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction (LSU Press, 2006)

- Hollandsworth Jr, James G. The Louisiana Native Guards: The Black Military Experience During the Civil War (LSU Press, 1995).

- Hollandsworth, James G. An Absolute Massacre: The New Orleans Race Riot of July 30, 1866 (LSU Press, 2001).

- Long, Alecia P. The Great Southern Babylon: Sex, Race, and Respectability in New Orleans, 1865—1920 (LSU Press, 2005).

- McCrary, Peyton. Abraham Lincoln and Reconstruction: The Louisiana Experiment (1978).

- Powell, Lawrence N. Reconstructing Louisiana(2001)

- Rabinowitz, Howard N. Race Relations in the Urban South 1865–1890 (Oxford UP, 1978).

- Rousey, Dennis Charles. Policing the Southern City: New Orleans 1805–1889 (LSU Press, 1996).

- Stout IV, Arthur Wendel. "A Return to Civilian Leadership: New Orleans, 1865–1866" (MA thesis, LSU, 2007). online bibliography pp. 58–62.

- Taylor, Joe Gray. Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863–1877 (LSU Press, 1974).

- Vincent, Charles. "Negro Leadership and Programs in the Louisiana Constitutional Convention of 1868." Louisiana History (1969): 339–351. in JSTOR

- Wetta, Frank J. The Louisiana Scalawags: Politics, Race, and Terrorism During the Civil War and Reconstruction (Louisiana State University Press; 2012) 256 pages

- White, Howard A. The Freedmen's Bureau in Louisiana (LSU Press, 1970).

Since 1900

- Allured, Janet. Remapping Second-Wave Feminism: The Long Women's Rights Movement in Louisiana, 1950–1997 (U of Georgia Press, 2016). xvi, 348 pp.

- Becnel, Thomas. Senator Allen Ellender of Louisiana: A Biography (1996)

- Bridges, Tyler. Bad Bet on the Bayou: The Rise of Gambling in Louisiana and the Fall of Governor Edwin Edwards (2002) excerpt and text search

- Fairclough, Adam. Race & Democracy: The Civil Rights Struggle in Louisiana, 1915–1972 (1999) excerpt and text search

- Haas, Edward F. The Age of the Longs, Louisiana, 1928–1960 (2001)

- Kurtz, Michael L. Louisiana Since the Longs, 1960 to Century's End (1998)

- Moore, John Robert. "The New Deal in Louisiana," in John Braeman et al. eds. The New Deal: Volume Two – the State and Local Levels (1975) pp. 137–65.

- Sanson, Jerry Purvis. Louisiana During World War II: Politics and Society, 1939–1945 (1999) excerpt and text search

- Schott Matthew J. Louisiana Politics and the Paradoxes of Reaction and Reform, 1877–1928 (2000)

- Schott, Matthew J. "Class conflict in Louisiana voting since 1877: some new perspectives." Louisiana History 12.2 (1971): 149–165. online

- Williams, T. Harry. Huey Long (1970), Pulitzer Prize

Local and regional

- Ancelet, Barry Jean, Jay D. Edwards, and Glen Pitre, eds. Cajun Country (1991)

- Clark, John G. New Orleans, 1718–1812: An Economic History (1970)

- Jeansonne, Glen. Leander Perez: Boss of the Delta (2006) excerpt and text search

Race and ethnicity

- Broussard, Sherry T. African Americans in Lafayette and Southwest Louisiana (Arcadia, 2012) online.

- Crouch, Barry A. "Black Education in Civil War and Reconstruction Louisiana: George T. Ruby, the Army, and the Freedmen’s Bureau." Louisiana History 38#3 (1997), pp. 287–308. online

- De Jong, Greta. A different day: African American struggles for justice in rural Louisiana, 1900–1970 (U of North Carolina Press, 2002) online.

- Gauthreaux, Alan G. Italian Louisiana: History, Heritage, & Tradition. (2019). online

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo. Africans in colonial Louisiana: the development of Afro-Creole culture in the eighteenth-century (LSU Press, 1995) online.

- Keele, Luke, William Cubbison, and Ismail White. "Suppressing black votes: a historical case study of voting restrictions in Louisiana." American Political Science Review 115.2 (2021): 694–700. online

- Scarpaci, Vincenza. "Walking the color line: Italian immigrants in rural Louisiana, 1880–1910." in Are Italians White? (Routledge, 2012) pp. 60–76.

- Vincent, Charles, ed. The African American Experience in Louisiana: From the Civil War to Jim Crow (Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana, 1999).

- Vincent, Charles. " 'Of Such Historical Importance...': The African American Experience in Louisiana." Louisiana History 50.2 (2009): 133–158 online.

19th century studies online

- Barbé-Marbois, François (1830). History of Louisiana: Particularly Of The Cession Of That Colony To The United States of America. Philadelphia: Carey & Lea. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Brackenridge, H.M. (1817). View of Louisiana; Containing Geographical, Statistical And Historical Notices Of That Vast And Important Portion Of America. Baltimore: Schaeffer & Maund. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Bunner, E. (1855). History of Louisiana, From Its First Discovery and Settlement To The Present Time. New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- French, Benjamin Franklin (1846). Historical Collections of Louisiana: Embracing Translations Of Rare And Valuable Documents Relating To The Natural, Civic And Political History Of That State. New York: Wiley and Putnam. Parts I, and II

- French, Benjamin Franklin (1853). Historical Memoirs of Louisiana, From The First Settlement Of The Colony To The Departure Of Governor O'Reilly In 1770. New York: Lamport, Blakeman & Law. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Fortier, Alcée (1894). Louisiana Studies. Literature, Customs and Dialects, History and Education. New Orleans: L. Graham & Son. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Fortier, Alcée (1904). A History of Louisiana. New York: Manzi, Joyant & Co. Volumes I, II, III, and IV

- Gayarré, Charles (1848). Romance of the History of Louisiana: A Series of Lectures. New York: D. Appleton & Company. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Gayarré, Charles (1852). Louisiana: Its History As A French Colony. New York: John Wiley. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Gayarré, Charles (1854). History of Louisiana. New York: Redfield. Volumes I, II, and III

- King, Grace; John R. Ficklen (1900). A History of Louisiana (4th ed.). New York: University Publishing Company. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Le Page Du Pratz, Antoine-Simon (1774). The History of Louisiana Or Of The Western Parts Of Virginia And Carolina. London: T. Becket. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- Martin, Francois Xavier (1829). The History of Louisiana From The Earliest Period. New Orleans: A. T. Penniman, & Co. Retrieved July 14, 2009.

- de Mézières, Athanase. Athanase de Mézières and the Louisiana-Texas Frontier, 1768–1780, (as translated and annotated by Herbert Eugene Bolton for publication in 1914). Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company. Volumes I and II

- Robertson, James Alexander (1911). Louisiana Under The Rule of Spain, France, and the United States 1785–1807. Cleveland: The Arthur H. Clark Company. Volumes I. and II.

External links

- History of Louisiana (includes complete text of Gayarré, and several other books)

- Boston Public Library, Map Center. Maps of Louisiana Archived November 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, various dates.

- Local History & Genealogy Reference Services, "Louisiana", Resources for Local History and Genealogy by State, Bibliographies & Guides, Washington DC: Library of Congress