Many steamboats operated on the Columbia River and its tributaries, in the Pacific Northwest region of North America, from about 1850 to 1981. Major tributaries of the Columbia that formed steamboat routes included the Willamette and Snake rivers. Navigation was impractical between the Snake River and the Canada–US border, due to several rapids, but steamboats also operated along the Wenatchee Reach of the Columbia, in northern Washington, and on the Arrow Lakes of southern British Columbia.

Types of craft

The paddle-wheel steamboat has been described as an economic "invasion craft" which allowed the rapid exploitation of the Oregon Country, a huge area of the North American continent eventually divided between the United States and Canada, and of Alaska and the Yukon.[1] Three basic types of steamboat were used on inland waterways: propeller, side-wheeler, and sternwheeler. Propellers required deeper draft than was commonly available on inland rivers, and side-wheelers required expensive docking facilities. Stern-wheelers were more maneuverable than side-wheelers and could make a landing just about anywhere. For these reasons, the stern-wheeler type was dominant over the propeller and the side-wheeler in almost all inland water routes.[1][2]

Economics of operations

Steamboats earned money by charging passengers fares and shippers for carrying cargo. Some vessels managed to carry as many as 500 people together with 500 tons of cargo. Passenger fares varied over time. In the early 1850s, fares for the Eagle, running from Oregon City and Portland, were $5 a trip for passengers and $15 per ton of freight.[3] During a gold rush, passenger fares were $23 for passage from Portland to Wallula, with various other charges, such as meals, in addition. Cargo was charged by the ton and by the distance carried. Sample rates in the early 1860s, following the establishment of a near monopoly on river transit, showed cargo rates running from $15 per ton for the haul from Portland to The Dalles (121 miles (195 km)), and $90 per ton for Portland to Lewiston (501) miles. A ton was not a unit of weight but a unit of volume, with cargo charges based on 40 cubic feet equalling one ton. Various chicaneries were practiced by the steamboat companies to increase the tonnage charges for items shipped.[2] One authority states that gross tonnage was measured at 100 cubic feet to the ton, which would still permit the steamboat companies to fix the "ton" for customer charges at 40 cubic feet.[1]

Steamboat capacity was measured by tonnage. Gross tonnage was the total volume capacity of the boat, while registered tonnage was the total theoretical volume that could be used to carry cargo or passengers once mechanical, fuel and similar areas had been deducted. For example, the sternwheeler Hassalo, built in 1880, was 160 feet (49 m) long, and rated at 462 gross tons and 351 registered tons.[1] Steamboat captains often became wealthy men. In 1858, the owners of the Colonel Wright paid her captain, Leonard Wright, $500 per month, an enormous amount of money for the time.[2]

Fuel and fuel consumption

Most steamboats burned wood, at an average rate of 4 cords an hour. Areas without much wood, such as the Columbia River east of Hood River, required wood to be hauled in and accumulated at wood lots along the river; eventually provision of fuel wood for steamboats itself became an important economic activity.[2]

Commodities shipped

Timmen reports that in 1867, Portland's exports totaled $6,463,793, of which about $4 million was gold dust and ingots mined from Idaho and Montana mines to be taken to the San Francisco mint. In 1870, the situation was similar. Other commodities hauled included lumber, agricultural products, salted salmon, and livestock. Once gold mines started winding down, the steamboats on the upper Columbia and Snake rivers carried wheat.[2]

Areas of operation

Lower, middle, and upper Columbia

Originally, the Columbia River was not considered navigable beyond its confluence with the Snake River just north of the Wallula Gap. This led to the somewhat misleading designations of stretch of the Columbia River from Wallula to its mouth as the lower, middle and upper river, generally defined as:

- The "lower river," meaning the routes from Astoria upriver to where the Willamette flows into the Columbia, and then up the Willamette to Portland or Oregon City. The lower river also included the run up the Columbia River Gorge from the mouth of the Willamette to the portage (and, later, locks) at the Cascades Rapids.

- The "middle river," meaning the route from the top of the Cascades to The Dalles, where another set of rapids began, called Celilo Falls, which required another and longer portage.

- The "upper river" meaning the route from Celilo Village, at the top of Celilo Falls, to Wallula Gap, near the mouth of the Snake River.[1]

Willamette River

The Willamette River flows northwards down the Willamette Valley until it meets the Columbia River at a point 101 miles (163 km)[2] from the mouth of the Columbia. In the natural condition of the river, Portland was the farthest point on the river where the water was deep enough to allow ocean-going ships. Rapids further upstream at Clackamas were a hazard to navigation, and all river traffic had to portage around Willamette Falls, where Oregon City had been established as the first major town inland from Astoria.

Snake River

The Snake River was navigable by steamboat from Wallula up to Lewiston, Idaho. Boats on this run included Lewiston, Spokane, and J.M. Hannaford. Imnaha and Mountain Gem were able to proceed 55 miles (89 km) upriver from Lewiston, through the Snake River Canyon, to the Eureka Bar, to haul ore from a mine that had been established there.[2]

Discontinuous inland routes on the Columbia

Far inland, the Columbia river was interrupted by rapids and falls, so much that it was never made freely navigable once Priest Rapids was reached above Pasco, Washington. There were important steamboat operations on many lakes that ultimately were tributary to the Columbia River, both in the United States and in Canada. These routes included Okanagan Lake, Arrow Lakes, Kootenay Lake and Kootenay River, and lakes Coeur d'Alene and Pend Oreille.

Early operations

Lower Columbia

Early operations on the Columbia were almost exclusively confined to the lower river. The first steamboat to arrive in Oregon was the Beaver, which was built in England and arrived at Oregon City on May 17, 1836.[4]

In the 1840s and 1850s, ocean-going ships equipped with auxiliary steam engines were able to and did come up the lower river as far as Portland, Oregon and Fort Vancouver. However, no other riverine steamboat worked in the region until the side-wheeler Columbia was launched in early June 1850, at Astoria. Columbia was a basic vessel, built with no frills of any kind, not even a passenger cabin or a galley. Her dimensions were 90 feet (27 m) in length, 16-foot (4.9 m) beam, 4-foot (1.2 m) of draft and 75 gross tons. On July 3, 1850, Columbia began her first run from Astoria to Portland and Oregon City. Columbia's first captain was Jim Frost, who had been a pilot on the Mississippi river. It took two days to get to Portland, largely because of the captain's lack of familiarity with the river channel and his resulting caution. After that, Columbia made the Oregon City-Portland-Astoria run twice a month at four miles per hour, charging $25 per passenger and $25 per ton of freight.[1][5]

Columbia held a monopoly on the river until December 25, 1850, when the side-wheeler Lot Whitcomb was launched at Milwaukie, Oregon. Lot Whitcomb was much larger than the Columbia (160 feet (49 m) long, 24-foot (7.3 m) beam, 5 feet (1.5 m) of draft, and 600 gross tons). and far more comfortable. Her engines were designed by Jacob Kamm, built in the eastern United States, then shipped in pieces to Oregon. Her first captain was John C. Ainsworth, and her top speed was 12 miles per hour (19 km/h). Lot Whitcomb charged the same rates as the Columbia and readily picked up most of her business. Lot Whitcomb was able to run upriver 120 miles (190 km) from Astoria to Oregon City in ten hours, compared to the Columbia's two days. She served on the lower river routes until 1854, when she was transferred to the Sacramento River in California, and renamed the Annie Abernathy.[1][5]

.jpg.webp)

The side-wheeler Multnomah made her first run in August 1851, above Willamette Falls. She had been built in New Jersey, taken apart into numbered pieces, shipped to Oregon, and reassembled at Canemah, just above Willamette Falls. She operated above the falls for a little less than a year, but her deep draft barred her from reaching points on the upper Willamette, so she was returned to the lower river in May 1852, where for the time she had a reputation as a fast boat, making for example the 18-mile (29 km) run from Portland to Vancouver in one hour and twenty minutes.[3]

Another sidewheeler on the Willamette at this time was the Mississippi-style Wallamet, which did not prosper, and was sold to California interests.[4] In 1853, the side-wheeler Belle of Oregon City, an iron-hulled boat built entirely in Oregon, was launched at Oregon City. Belle (as generally known) was notable because everything, including her machinery, was of iron that had been worked in Oregon at a foundry owned by Thomas V. Smith. Belle lasted until 1869, and was a good boat, but was not considered a substitute for the speed and comfort (as the standard was then) of the departed Lot Whitcomb. Also operating on the river at this time were James P. Flint, Allen, Washington, and the small steam vessels Eagle, Black Hawk, and Hoosier, the first two being iron-hulled and driven by propellers.[3][4]

Jennie Clark, built by Jacob Kamm with John C. Ainsworth as her first captain, was placed in service in February 1855. She was the first sternwheeler on the Columbia River system. Her hull and upper works were built at Milwaukie, while her engines were built in Baltimore to Kamm's specifications, for a price of $1,663.16, and shipped around to the West Coast, which cost another $1,030.02. Kamm and Ainsworth had settled on the sternwheeler as superior to propeller-driven and side-wheel boats. Propellers were too vulnerable to expensive-to-fix damage to propellers and shafts from rocks and other obstructions in the river. Sidewheelers were too difficult to steer and needed expensive dock facilities.[4]

Middle Columbia

.jpg.webp)

Operations on the middle Columbia were hampered by the existence of the Cascades Rapids, which blocked all upriver traffic and substantially impeded everything going downriver. In 1850, Francis A. Chenowith built a mule-drawn portage railway around the rapids on the north side of the river. In 1851, he sold out to Daniel F. and Putnam Bradford, who, together with J.O. Van Bergen built the James P. Flint at the lower end of the Cascades, then winched her along the bank to operate on the middle river up to The Dalles. Business wasn't enough on this run, as overland emigration had fallen off, so in 1852, her owners winched her back down along the bank of the Cascades to the lower river. In September, 1852, the Flint struck a rock and sank, but was raised, equipped with the engines out of the Columbia, and renamed the Fashion. The next steamboat on the middle river was the propeller Allan, which was hauled up over the Cascades from the lower river in 1853. Business increased, so by 1854, Allan's owners were able to put a second boat on the middle river run, the side-wheeler Mary. By 1858, the Bradfords, who had the portage railway on the north side of the Cascades, faced competition on the south side from the Oregon Portage Railroad, also mule-hauled.[2][4]

In 1868, the United States Army Corps of Engineers made the first of what would be many permanent alterations to the river, blasting out rocks at the mouth of the John Day River. In 1877, work began on a canal around the Cascades Rapids, which was completed in 1896. The Dalles-Celilo Canal was completed in 1915.[6]

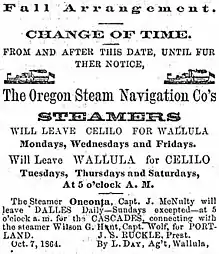

Upper Columbia

The first steamboat intended for operation above Celilo Falls was the Venture, built near the Cascades, with the objective of hauling her around Celilo and putting her to run on the upper river. This never happened, as upon launch, the Venture was swept over the Cascades, and damaged by hitting a rock on the way down. The Colonel Wright, launched October 24, 1858, at the mouth of the Deschutes River, was the first steamboat to operate on the upper Columbia. In 1860, the owners of Wright built another boat, the Tenino, at Celilo Falls, which proved to be immensely profitable.[2] Eventually the Oregon Steam Navigation Company built a portage railroad on the south side of the river that ran between The Dalles and Celilo.

Snake River

The Snake River wound through wheat-producing regions of eastern Washington. Farmers in these areas wanted to ship their products out as cheaply as possible, and looked to riverine transport as a way to do it. The problem was there were too many rapids and other obstructions to allow economic use of the river in its natural state. O.S.N. pressured the government to do something about this, and so in 1867, the Corps of Engineers launched a two year survey of the upper Columbia and the Snake River, targeting rapids and other areas for work to improve navigability. During the next few years, rapids and obstructions at various points in both these rivers were removed or meliorated, largely at government expense.[2]

Rise of monopoly power over the river

In about 1860, the Bradford brothers, R.R. Thompson, Harrison Olmstead, Jacob Kamm, and steamboat captains John C. Ainsworth and L.W. Coe formed the Oregon Steam Navigation Company which quickly gained monopoly power over the most of the boats on the Columbia and Snake rivers, as well as the portages at the Cascades and from The Dalles to Celilo. The O.S.N. monopoly lasted from about 1860 to 1879, when its owners sold out to the Oregon Railroad and Navigation Company ("OR&N") and realized an enormous profit.

O.R. & N was an enterprise of Henry Villard and ten partners who raised $6 million in an effort to expand the O.S.N. monopoly to control all rail and steamboat transport in Oregon and the Inland Empire. Purchase of O.S.N. gave Villard and his allies control over just about every steamboat then operating on the Columbia, including all the OSN boats already mentioned, plus Emma Hayward, S.G. Reed, Fannie Patton, S.T.Church, McMinnville, Ocklahama, E.N. Cook, Governor Grover, Alice, Bonita, Dixie Thompson, Welcome, Spokane, New Tenino, Almota, Willamette Chief, Orient, Occident, Bonanza, Champion, and D.S.Baker.

Railway completion forces steamboats off routes

In April, 1881, O.R.& N. completed railways on the south side of the river from Celilo to Wallula, and, in October 1882, from Portland to The Dalles. This left the middle Columbia expensive to navigate because of the need to surmount two portages on the way upriver. O.R.& N. started bringing its boats down to the lower river from the middle and upper stages, with the strategy of forcing patrons to use its railroads rather than its steamboats. Harvest Queen was taken over Celilo Falls in 1881 from the upper to the middle river under the command of captain Troup. Troup brought D.S. Baker over Celilo in 1888. and in 1893, over the Cascades.[2]

Villard, in control of O.R. & N then made one of his biggest mistakes when he brought from the east coast two enormous iron-hulled vessels, Olympian and Alaskan, and placed them on routes on the Columbia and Puget Sound. The huge size and expense of these vessels precluded them from ever making a profit.

Opposition to O.R.& N. began to arise in 1881 on the lower and middle Columbia. Captain U.B. Scott formed a concern with L.B. Seely and E.W. Creighton to put Fleetwood, a propeller boat, on the run up to the Cascades. Gold Dust was hauled over the Cascades to compete on the middle river. This competition lowered fares down to 50 cents from Portland to The Dalles.[2] Another competitor which arose in about 1880 was the Shaver Transportation Company.

.jpg.webp)

As the railroads were building on the south bank of the Columbia neared competition, O.R.& N. withdrew its boats from the middle and upper river. This was done by running the boats over the Cascades and Celilo Falls, generally at high water. In 1881, Captain James W. Troup took Harvest Queen from the upper river over Celilo Falls into the middle river. In 1890 Captain Troup took her over the Cascades into the lower river. Troup brought D.S. Baker over Celilo Falls in 1888, and then over the Cascades in 1893.[2]

In one famous incident, on May 26, 1888, Troup brought Hassalo over the Cascades at close to 60 miles (97 km) an hour as 3,000 people watched. By 1893, the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company had completed a route all along the south side of the river. As a result, steamboating virtually ended on the Columbia and Snake Rivers above the Dalles, at least until November 1896, when the Cascade Locks and Canal were completed, allowing open river navigation all the way from Portland to The Dalles.[7]

Lock and canal improvements to the river

As rail competition grew, and forced steamboats off their old routes, shippers and steamboat lines began agitating Congress to allocate funds for improvements to the river, in the form of canals and locks, that would restore their competitive position relative to the railroads. The two main improvements on the Columbia were the Cascade Locks and Canal, completed in 1896, and the Celilo Canal and Locks, completed in 1915. While these projects did open the river first to The Dalles, and then all the way to Wallula, there was no long-term improvement for the steamboats' position in their losing competition against the railroads.

Late steamboat operations

_1901.jpg.webp)

By 1899, although rail competition had become severe, new steamboats continued to be built, including some of the fastest and most well-designed vessels. In that year, Altona was rebuilt for the Yellow Stack line, and a brand new Hassalo was launched for the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company. The new Hassalo reached 26 miles (42 km) an hour during trials, supposedly the fastest in the world, although this was disputed by her rivals. Regulator was rebuilt, and way upstream, at Potlatch, Idaho, the J.M. Hannaford was launched, unusual as she was built in the Mississippi style, with two stacks forward of her pilot house, instead of the single stack aft, as was the design for the vast majority of other Columbia River boats ever since the Jennie Clark. Several boats were rebuilt in 1900, and in 1901, newly constructed vessels included the Charles R. Spencer, an elegant passenger vessel intended for the Portland-The Dalles run, whose whistle was reportedly so powerful it could "make rotten piles totter." The Charles R. Spencer had to have been built prior to May 28, 1896. The Library of Congress has a stereograph copyrighted on that date of the Charles R. Spencer and the Bailey Gatzert. Inquire to the Library of Congress for reproduction number LC-USZ62-54736, Sternheelers in Cascade Locks 1896. Other new vessels included the freighter/towboats F.B. Jones, and M.F. Henderson. As with other years, several vessels were reconstructed.[8]

Last years

By 1915, steamboat operations had dropped sharply, and the only boats regularly running on the Columbia above Vancouver were few, mainly the Bailey Gatzert and the Dalles City, with the Bailey running excursions and passenger traffic from Portland to The Dalles, and Dalles City running freight and passengers along the same route, but making more stops. Downriver to Astoria, the T.J. Potter had been condemned in 1916, and, with some exceptions, the boats of Harkins Transportation Company, including the new steam propeller Georgiana (built 1914), were the only major boats on the river.

Final decline

The Bailey Gatzert excursion runs up the Columbia came to an end in 1917 when the Bailey was transferred to Seattle, Washington, to serve the Seattle-Bremerton route, then much in demand because of wartime marine construction at the Bremerton Navy Yard.[9] Railroad and highway construction in the early 1920s finished off the steamboat trade. By 1923, major passenger and freight steamboat operations on the lower and middle Columbia had ceased, except for towboats, and until 1937, the passenger and freight boats of the Harkins Transportation Company on the lower Columbia, such as Georgiana. For a brief time, in 1942, the now-famous Puget Sound propeller steamer Virginia V was brought down to the Columbia river, thus becoming (although it was not known at the time) the last survivor of the wooden steamboat fleets of both Puget Sound and of the Columbia River.[10]

Last runs

The Georgie Burton was one of the last surviving steamboats on the Columbia River. She had been launched in 1906, on the same day as the San Francisco earthquake. Her last commercial run came on March 20, 1947. The trip was described in McCurdy as follows:

[She]pulled away from her Portland dock ... her whistle being the traditional three blast farewell to sentimental Portlanders who waited on the riverbank to see her pass. At Vancouver, Washington, she tied up to take on a special crew of old-time river men. Capt. George M. Shaver, who had run the upper river to Big Eddy in the early days when the Shaver boats were on The Dalles run, was senior pilot. Veteran river masters took their turns at the wheel ... all great names on the river in the days of tall smokestacks and thundering paddle-buckets. ... All along the river, groups of school children, and grownups too, came out to watch the Georgie Burton pass.[11]

Mills, an English professor when he was not writing books on history, used his full talent with the language to capture the occasion:

On up the Columbia the Georgie Burton sloshed along while the fog thinned and the sky brightened. She passed familiar places, the sights passengers watched for and remembered, like Cape Horn and Multnomah Falls. She reached the lower Cascades and entered the tall lock of Bonneville Dam. Slowly the lock filled and the Georgie Burton slid out into the slack water beyond, riding over what had been the awesome Cascades, now nothing more than a quiet pool. ... A captain pointed out where the Regulator had hanged herself on a rock, and another one remembered the Fashion. Here was where Hassalo went nearly a mile a minute through the rapids. ... Near Hood River, where the gorge widens, the Spencer had broken her back in the gale, and the big twin-stackers Oneonta and Iris had brought a touch of Upper Mississippi to the Columbia.[12]

Georgie Burton was moored up at The Dalles, with the objective of turning her into a museum boat. Unfortunately the great Columbia River flood of 1948 broke her loose from her mooring and wrecked her.

The last steamboat race on the Columbia was held in 1952, between Henderson and the new steel-hulled Portland, both towboats. This was actually more of an exhibition than a race. The famous actor James Stewart and other members of the cast of the recently filmed movie Bend of the River were on board the Henderson. The race was witnessed by Capt. Homer T. Shaver, who stated that as both were running fast for their design, as towboats, the speeds were not much compared to what he'd seen as a young man on the river. Again, the results were summed up by McCurdy:

It was, however, a stirring sight as the two paddlers, smoke pouring from their stacks and stately waterfalls at their sterns, re-enacted the glory days of steamboating on the Columbia. And this time the sentimental favorite, the old wooden Henderson, beat the new steel Portland.[13]

In 1995, there was a "race" (again, more of an exhibition) between the steam-powered sternwheeler Portland and the diesel-powered excursion sternwheeler Columbia Gorge. The vessels picked up their passengers at the seawall in Portland, ran north about to the Fremont Bridge, then "raced" south down the Willamette. The images above show the boats passing under the lifting spans of the Burnside Bridge.

Wrecks

Boats were lost for many reasons, including striking rocks or logs ("snags"), fire, boiler explosion, or puncture or crushing by ice. Sometimes boats could be salvaged, and sometimes not.

Surviving vessels

Moyie and Sicamous are the only surviving sternwheelers from before 1915. (No sidewheelers survive.) Neither is operational, and both are kept permanently out of water. They are preserved as museums. These are unique as they are both from the time of passenger-carrying steamboats in the Pacific Northwest. Moyie is said to be the oldest surviving vessel of her kind, and this is probably true.

Only one operational sternwheel steamboat survives on the entire Columbia River system, north or south of the border, and that is the Portland, moored at Portland, Oregon. Unlike Sicamous and Moyie, Portland never carried passengers on a regular basis, but was built as a towboat. The steel-built steam tug Jean is also in Portland, but has been stripped of her paddle wheel and is lying in a semi-derelict state in North Portland Harbor (Oregon Slough).

Another boat, W.T. Preston, a Corps of Engineers snagboat, survives as a museum at Anacortes and is reported to be operational. Unlike Portland however, W.T. Preston is not kept in the water. The propeller steamer Virginia V which technically may have been the last wooden steamboat in regular commercial passenger service on the Columbia (in 1942) has been restored and is operational in Seattle, Washington.

Replica steamboats

Much later, starting in the early 1980s, a number of replica steamboats have been built, for use as tour boats in river cruise service on the Columbia and Willamette Rivers. Although still configured as sternwheelers, they are non-steam-driven boats or ships, also called motor vessels, powered instead by diesel engines. These tourism-focussed vessels range in size from the 65-foot (20 m) Rose to the 360-foot (110 m) American Empress (formerly Empress of the North). Others include the M.V. Columbia Gorge, the Willamette Queen, and the Queen of the West.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Affleck, Edward L., A Century of Paddlewheelers in the Pacific Northwest, the Yukon, and Alaska, Alexander Nicholls Press, Vancouver, B.C. 2000 ISBN 0-920034-08-X

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Timmen, Fritz, Blow for the Landing, Caxton Printers, Caldwell, ID 1972 ISBN 0-87004-221-1

- 1 2 3 Corning, Howard McKinley, Willamette Landings, Oregon Historical Society, Portland, OR (2nd Ed. 1973) ISBN 0-87595-042-6

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mills, Randall V., Sternwheelers up Columbia, University of Nebraska, 1947. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7

- 1 2 Gulick, Bill, Steamboats on Northwest Rivers, Caxton Press, at 15-21, Caldwell, Idaho (2004) ISBN 0-87004-438-9

- ↑ Ulrich, Roberta (2007). Empty Nets: Indians, dams, and the Columbia River. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-87071-469-4.

- ↑ Newell, Gordon R., Ed., H.W.Curdy Marine History of the Pacific Northwest, at 5, Superior Publishing, Seattle, WA 1966 ("McCurdy")

- ↑ McCurdy, at 48 and 70

- ↑ McCurdy, at 291

- ↑ Kline, M.S., Steamboat Virginia V, at page 56, Documentary Books Publishers, Bellevue, WA 1985 ISBN 0-935503-00-5

- ↑ McCurdy, at 545

- ↑ Mills, at 183

- ↑ McCurdy, at 583

External links

Photograph links

Typical craft and uses

- Norma This image shows use of sternwheeler as a tug on the Columbia river, pushing a barge loaded with railcars, combining two transportation modes.

- Harvest Queen acting as tug for sailing vessel, Astoria 1906 As with the image of Norma acting as a tug for a rail car barge upriver, this image shows the versatility of sternwheelers in being able to assist oceangoing ships as well.

- Service, Cowlitz, and Nestor tied up at a dock, sometime in 1920s This shows three typical everyday working steamboats, one, Service, with three decks, and the remaining smaller boats with only two.

- Hattie Bell, at Rooster Rock, lower Columbia River Shows the deep water of the Columbia close to shore by Rooster Rock at the west end of the Columbia Gorge and how close steamboats could run by the shore in this area.

- Northwestern, probably on the Willamette River This photograph shows the narrowness of the Willamette River compared to the Columbia and also the wooden awning over the foredeck common on many Willamette river steamboats.