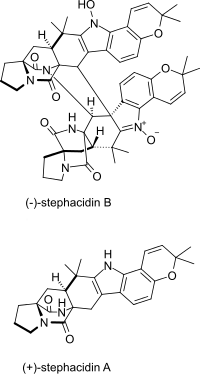

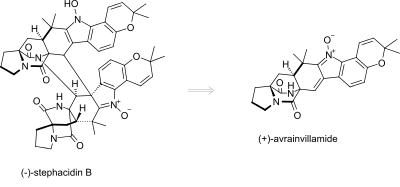

Stephacidin A and B are antitumor alkaloids isolated from the fungus Aspergillus ochraceus [1] that belong to a class of naturally occurring 2,5-diketopiperazines.[2] This unusual family of fungal metabolites are complex bridged 2,5-diketopiperazine alkaloids that possess a unique bicyclo[2.2.2]diazaoctane core ring system and are constituted mainly from tryptophan, proline, and substituted proline derivatives where the olefinic unit of the isoprene moiety has been formally oxidatively cyclized across the α-carbon atoms of a 2,5-diketopiperazine ring. The molecular architecture of stephacidin B, formally a dimer [3] of avrainvillamide, reveals a complex dimeric prenylated N-hydroxyindole alkaloid that contains 15 rings and 9 stereogenic centers and is one of the most complex indole alkaloids isolated from fungi. Stephacidin B rapidly converts into the electrophilic monomer avrainvillamide in cell culture, and there is evidence that the monomer avrainvillamide interacts with intracellular thiol-containing proteins, most likely by covalent modification.[4]

Avrainvillamide, which contains a 3-alkylidene-3H-indole 1-oxide function, was identified in culture media from various strains of Aspergillus and is reported to exhibit antimicrobial activity against multidrug-resistant bacteria.[5] The avrainvillamide and stephacidins family of structurally complex anticancer natural products are active against the human colon HCT 116 cell line.[6] The signature bicyclo[2.2.2]diazaoctane ring system common to these alkaloids has inspired numerous synthetic approaches.[7]

References

- ↑ Qian-Cutrone J, Huang S, Shu YZ, Vyas D, Fairchild C, Menendez A, Krampitz K, Dalterio R, Klohr SE, Gao Q (December 2002). "Stephacidin A and B: two structurally novel, selective inhibitors of the testosterone-dependent prostate LNCaP cells". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (49): 14556–14557. doi:10.1021/ja028538n. PMID 12465964.

- ↑ Borthwick AD (2012). "2,5-Diketopiperazines: Synthesis, Reactions, Medicinal Chemistry, and Bioactive Natural Products". Chemical Reviews. 112 (7): 3641–3716. doi:10.1021/cr200398y. PMID 22575049.

- ↑ von Nussbaum F (2003). "Stephacidin B-A new stage of complexity within prenylated indole alkaloids from fungi". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 42 (27): 3068–3071. doi:10.1002/anie.200301646. PMID 12866092.

- ↑ Wulff JE, Herzon SB, Siegrist R, Myers AG (April 2007). "Evidence for the rapid conversion of stephacidin B into the electrophilic monomer avrainvillamide in cell culture". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 129 (16): 4898–4899. doi:10.1021/ja0690971. PMC 3175819. PMID 17397160.

- ↑ Sugie Y, Hirai H, Inagaki T, Ishiguro M, Kim YJ, Kojima Y, Sakakibara T, Sakemi S, Sugiura A, Suzuki Y, Brennan L (2001). "A new antibiotic CJ-17,665 from Aspergillus ochraceus". The Journal of Antibiotics. 54 (11): 911–916. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.54.911. PMID 11827033.

- ↑ Baran PS, Hafensteiner BD, Ambhaikar NB, Guerrero CA, Gallagher JD (July 2006). "Enantioselective total synthesis of avrainvillamide and the stephacidins". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (26): 8678–8693. doi:10.1021/ja061660s. PMID 16802835.

- ↑ Escolano C (December 2005). "Stephacidin B, the avrainvillamide dimer: A formidable synthetic challenge". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 44 (47): 7670–7673. doi:10.1002/anie.200502383. PMID 16252300.