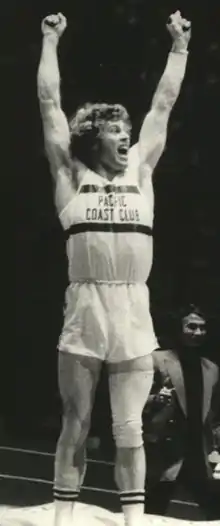

Smith in 1973 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Birth name | Stephen Norwood Smith |

| Nationality | American |

| Born | November 24, 1951 Long Beach, California, U.S.[1] |

| Died | September 23, 2020 (aged 68) |

| Height | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m)[1] |

| Weight | 181 lb (82 kg)[1] |

| Sport | |

| Sport | Track and Field |

| Event | Pole vault |

| Club | Pacific Coast Club |

| Achievements and titles | |

| Personal best | 5.61 m (18 ft 5 in) (1975)[1][2] |

Stephen Norwood Smith (November 24, 1951 – September 23, 2020) was an American Olympic pole vaulter.[3] He was the first person to clear the 18 foot barrier indoors.[1] He was the number one ranked pole vaulter in the world in 1973.

Athletic career

Smith was United States indoor pole vault champion in 1972–73.[4] He was also the first vaulter to break the 18-foot barrier indoors in 1973.[1]

Smith qualified for the 1972 Munich Olympics but failed to make the final.[1] In the Olympic trials, Smith finished second in a top-quality competition – Bob Seagren, the winner, broke the world record.[5] At the Olympics, Smith was one of the athletes affected by a ban by the world governing body the IAAF on the lighter poles they had been using all season. An initial ban in July had been reversed on August 27, but on the eve of the competition, August 30, the IAAF reimposed their ban claiming the poles were new equipment and therefore invalid. Smith finished 18th in qualifying and was so upset he threw his pole away in disgust at the end of the competition.[6][7]

Following his Olympic disaster, Smith rededicated himself to pole vaulting. His reward came on January 20, 1973 when he broke the world record indoors with 17 ft 11 in (5.46 m) (beating a record previously held by Kjell Isaksson at (17 ft 10.5 in (5.45 m)).[8] Six days later he raised the record to 18 ft 0.25 in (5.49 m).[9][10] Smith was to raise the record again over the next two seasons on the ITA tour culminating with 5.61 m (18 ft 5 in) on May 28, 1975 in New York City.[11][12]

He had a long-standing sporting rivalry with his fellow American pole vaulter Bob Seagren that famously developed into a personal and very public animosity.[13]

This rivalry was used as a promotional item for the new professional track and field tour of the International Track Association (ITA) that Smith and Seagren both joined – Seagren from the start of the ITA in 1973, Smith for the 1974 season.[14] After the ITA folded in 1976, Smith applied to regain his amateur status having it restored eventually in 1979. He pursued legal action to enable him to take part in the Olympic Trials for the 1980 Moscow Olympics from which he was initially banned. Smith finished fourth at the trials making him the alternate if one of top three finishers could not compete. However, this status was made meaningless with the United States boycott of the Moscow Olympics.[5]

Smith retired from athletics in 1983 after suffering an ankle injury in a car accident.[15]

Smith, a natural showman, was always popular with the crowds, for his muscular physique, love of surfing and his eye-catching dress sense – he famously competed in cranberry-colored, psychedelic ski pants.[9]

Early life

Smith attended South Torrance High School. He was the CIF California State Meet champion in the event in 1968, defeating the namesake son of double Olympic pole vault champion Bob Richards on fewer misses.[16]

His first college was the University of Southern California. He started the year his nemesis, Bob Seagren, graduated. After one year he left for Long Beach State. At Long Beach State he was refused permission to work with his coach, Dick Tomlinson, who was not on the college staff, so he ended up training with the Pacific Coast Club instead.[9][17]

Later life

Smith became a real-estate agent in southern California after retiring.[18]

World rankings

Smith was voted by the experts at Track and Field News to be ranked among the best in the USA and the world at the pole vault during his career. He was ranked during his early career and again when he returned to amateur competition. He would also have ranked during his professional career in the intervening years if the rankings had allowed this.[19][20]

| Year | World rank | US rank |

|---|---|---|

| 1969 | – | 8th |

| 1971 | – | 4th |

| 1972 | 6th | 4th |

| 1973 | 1st | 1st |

| 1980 | – | 8th |

Accolades

In 2012, Smith was inducted into the United States National Pole Vault Hall of Fame.[21]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Steve Smith. sportsreference.com

- ↑ Steve Smith. trackfield.brinkster.net

- ↑ "Steve Smith". Olympedia. Retrieved September 24, 2020.

- ↑ USA Indoor Track & Field Champions, Men's Pole Vault, USA Track & Field.

- 1 2 R. Hymans (2008) The History of the United States Olympic Trials – Track & Field. USA Track & Field.

- ↑ Steve Breazeale (August 2, 2012) "Not Your Typical Olympic Story", San Clemente Times.

- ↑ Mike Rosenbaum. "Americans Pole-Axed: Olympic Pole Vault Controversy", trackandfield.about.com. Retrieved March 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Steve Smith Sets Pole Vault Record", Associated Press, Reading Eagle, January 21, 1973.

- 1 2 3 Ron Reid (February 12, 1973) "He's Raising The Roof A week after setting the world record, Steve Smith wins coast to coast and it seems the sky is his limit", Sports Illustrated.

- ↑ "Long Beach's Steve Smith Sets New Mark For Indoor Pole Vaulting At 18 Feet", Associated Press, Gettysburg Times, (January 27, 1973).

- ↑ Joe Marshall (June 4, 1979) "He Gets Up By Being Down On Himself", Sports Illustrated.

- ↑ "Record Night in Pokey", The Spokesman-Review, February 25, 1974.

- ↑ "Pole-vaulters Seagren and Smith: Champions and Competitors, Yes—but Chums? No Way", People, Vol. 3 No. 21, June 2, 1975.

- ↑ Joseph M. Turrini (2010). The End of Amateurism in American Track and Field. University of Illinois Press. pp. 123–. ISBN 978-0-252-07707-4.

- ↑ Jeff Pearlman (June 29, 1998). "Steve Smith, Olympic Pole Vaulter", Sports Illustrated.

- ↑ California State Meet Results – 1915 to present. prepcaltrack.com

- ↑ Olympians By Year, Traditions, Official Site of Long Beach State Athletics, longbeachstate.com. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ↑ "Steve Smith", Altera Real Estate. Retrieved March 16, 2013.

- ↑ "World Rankings Index—Men's Pole Vault" (PDF). Track and Field News.

- ↑ "U.S. Rankings Index—Men's Pole Vault" (PDF). Track and Field News. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2007.

- ↑ Inductees, National Pole Vault Hall of Fame, usapolevaulting.org.