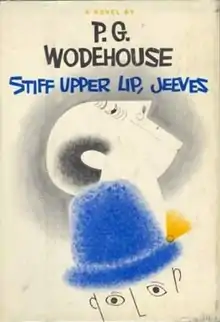

First edition (US) | |

| Author | P. G. Wodehouse |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Series | Jeeves |

| Genre | Comic novel |

| Publisher | Simon & Schuster (US) Herbert Jenkins (UK) |

Publication date | 22 March 1963 (US) 16 August 1963 (UK) |

| Media type | Print (Hardback) |

| Pages | 190 |

| OCLC | 3601985 |

| Preceded by | Jeeves in the Offing |

| Followed by | Much Obliged, Jeeves |

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves is a novel by P. G. Wodehouse, published in the United States on 22 March 1963 by Simon & Schuster, Inc., New York, and in the United Kingdom on 16 August 1963 by Herbert Jenkins, London.[1] It is the ninth of eleven novels featuring Bertie Wooster and his valet Jeeves.

Chronicling Bertie Wooster's return to Sir Watkyn Bassett's home, Totleigh Towers, the story involves a black amber statuette, an Alpine hat, and a dispute between the engaged Gussie Fink-Nottle and Madeline Bassett concerning vegetarianism.

Plot

Jeeves comes home after serving as a substitute butler at Brinkley Court, the country house of Bertie's Aunt Dahlia. She tells Bertie that Sir Watkyn Bassett was there and was impressed with Jeeves. Additionally, Sir Watkyn bragged about obtaining a black amber statuette to Aunt Dahlia's husband, Tom Travers, who is a rival collector.

Jeeves dislikes Bertie's new blue Alpine hat with a pink feather. Bertie continues to wear the hat, and has lunch with Emerald Stoker, the sister of his friend Pauline Stoker who is on her way to the Bassett household, Totleigh Towers. He then sees Reverend Harold "Stinker" Pinker, who is upset that Sir Watkyn has not given him the vicarage, which Stinker needs to be able to marry Stephanie "Stiffy" Byng, Watkyn Bassett's niece. Stinker tells Bertie that Stiffy wants Bertie to come to Totleigh Towers to do something for her, but knowing that Stiffy often starts trouble, Bertie refuses.

Gussie Fink-Nottle is upset with his fiancée Madeline Bassett, Sir Watkyn's daughter. Jeeves suggests that Bertie go to Totleigh Towers there to heal the rift between Gussie and Madeline, or else Madeline will decide to marry Bertie instead. Though Bertie does not want to marry Madeline, his personal code will not let him turn a girl down. Bertie reluctantly decides to go to Totleigh, saying, “Stiff upper lip, Jeeves, what?”.[2] Jeeves commends his spirit.

At Totleigh Towers, Madeline is touched to see Bertie, thinking he came to see her because he is hopelessly in love with her. Sir Watkyn's friend Roderick Spode, formally Lord Sidcup, loves Madeline but hides his feelings from her. At dinner, Madeline says that her father purchased the black amber statuette from someone named Plank who lives nearby at Hockley-cum-Meston. Stiffy says the statuette is worth one thousand pounds.

Jeeves tells Bertie that Gussie is unhappy with Madeline because she is making him follow a vegetarian diet. The cook has offered to secretly provide Gussie steak-and-kidney pie. The cook is in fact Emerald Stoker, who took the job after losing her allowance betting on a horse. She has fallen for Gussie.

After telling Bertie that Sir Watkyn cheated Plank by paying only five pounds for the statuette, Stiffy orders Bertie to sell it back to Plank for five pounds, or else she will tell Madeline that Gussie has been sneaking meat, and then Madeline would leave him for Bertie. Stiffy takes the statuette and gives it to Bertie. Bertie goes to Hockley-cum-Meston and meets the explorer Major Plank. Plank mentions that he is looking for a prop forward for his Hockley-cum-Meston rugby team.

"Nasty hangdog look the fellow's got. I suspected from the first he was wanted by the police. Had him under observation for a long time, have you?"

"For a very long time, sir. He is known to us at the Yard as Alpine Joe, because he always wears an Alpine hat."

"He's got it with him now."

"He never moves without it."

— Plank and Inspector Witherspoon discuss Alpine Joe[3]

When Bertie tries to sell the statuette back to him for five pounds, Plank assumes Bertie stole it from Sir Watkyn, and intends to call the police. Jeeves arrives, saying he is Chief Inspector Witherspoon of Scotland Yard. He tells Plank that he is there to arrest Bertie, claiming that Bertie is a criminal known as Alpine Joe. Leading Bertie safely away, Jeeves tells him that Sir Watkyn actually paid the full one thousand pounds for the statuette and had lied to spite Tom Travers. Jeeves returns the statuette to Totleigh Towers.

Spode sees Gussie kissing Emerald, and threatens to harm him for betraying Madeline. When Stinker moves to protect Gussie, Spode hits Stinker. Stinker retaliates, knocking out Spode. Spode regains consciousness, only to be knocked out again by Emerald. Seeing Spode on the ground, Madeline calls Gussie a brute. He defiantly eats a ham sandwich in front of her, and their engagement ends. Gussie and Emerald elope. Sir Watkyn offers Harold Pinker the vicarage, but changes his mind when he finds out that Stinker punched Spode. Meanwhile, Madeline resolves to marry Bertie.

Major Plank, after learning from a telephone call with Inspector Witherspoon that Harold Pinker is a skilled prop forward, comes to the house and gives him the vicarage at Hockley-cum-Meston. Because of this, Stiffy no longer needs the statuette, which she stole a second time to blackmail Sir Watkyn, so she gives it to Jeeves to return it.

Hiding from Plank behind a sofa, Bertie overhears Spode and Jeeves convince Madeline that Bertie did not come to Totleigh Towers for love of her but rather because he wanted to steal the statuette, which Jeeves says he found among Bertie's belongings. Madeline decides not to marry Bertie. Spode proposes to Madeline and she accepts. Bertie is discovered and Sir Watkyn, a justice of the peace, intends to make Bertie spend twenty-eight days in jail. After being arrested by Constable Oates, Bertie spends the night in jail. In the morning, Bertie is released. Sir Watkyn is dropping the charge because Jeeves agreed to work for him. Bertie is shocked, but Jeeves assures him it will only be temporary. After a week or so, he will find a reason to resign and return to Bertie. Moved, Bertie wishes there was something he could do to repay Jeeves. Jeeves asks Bertie to give up the Alpine hat. Bertie agrees.

Style

Jeeves's language is essentially static throughout the series, which is related to his role in maintaining stability and protecting Bertie from forces of change; on the other hand, Bertie works as the force for creating openness and conflict in the stories, and his language is similarly spontaneous. He often tries to work out the best way to express something while speaking to another character or narrating the story. Many times, he asks Jeeves for help finding the correct word or quotation to use, which also leads to the comic juxtaposition of Bertie's use of slang with Jeeves's formal speech. For example, in chapter 13:

"Hell's foundations are quivering. What do you call it when a couple of nations start off by being all palsy-walsy and then begin calling each other ticks and bounders?"

"Relations have deteriorated would be the customary phrase, sir."

"Well, relations have deteriorated between Miss Bassett and Gussie."[4]

In keeping with the dynamic nature of his language, Bertie learns words and phrases from Jeeves throughout the stories. One example of this is the word "contingency". First used by Jeeves in "The Inferiority Complex of Old Sippy", Bertie repeats the word in chapter 18 of Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves: "I was thankful that there was no danger of this contingency, as Jeeves would have called it, arising".[5]

Wodehouse uses many allusions and makes comical changes to quotations, sometimes by stating the quotation without changing the citation itself but adding something in the context to make the quote relevant to the situation in an absurd way. An instance of this can be seen in an allusion to Longfellow's poem "Excelsior" in chapter 8: "However much an Aberdeen terrier may bear 'mid snow and ice a banner with the strange device Excelsior, he nearly always has to be content with dirty looks and the sharp, passionate bark".[6]

In chapter 5, Bertie reacts strongly when he hears that Sir Watkyn Bassett wants to hire Jeeves: "I reeled, and might have fallen, had I not been sitting at the time". This is a variation on a quote from Bram Stoker's Dracula, describing Arthur after he stakes Lucy in her grave: "The hammer fell from Arthur's hand. He reeled and would have fallen had we not caught him".[7]

Wodehouse often has Bertie referring to words with abbreviations, particularly by their initial letters alone, with the meaning of these words being obvious from the context. This can be seen in the last line of chapter 3 and the first of chapter 4:

"Paddington!" he shouted to the charioteer, and was gone with the wind, leaving me gaping after him, all of a twitter.

And I'll tell you why I was all of a t.[8]

Bertie frequently draws imagery from musical theatre, emphasizing the degree to which the narrative resembles a comedic stage production. Gestures or statements made by characters are sometimes likened to theatrical conventions. For instance, Bertie describes Madeline's reaction when she thinks Gussie has knocked Spode out in chapter 15: "'I hate you! I hate you!' cried Madeline, a thing I didn't know anyone ever said except in the second act of a musical comedy".[9]

Background

The fictional Hockley-cum-Meston rugby team, the rugby team managed by Plank in the novel, appeared in the earlier Jeeves story "The Ordeal of Young Tuppy", published in 1930.

Wodehouse had determined much of the novel's plot by the end of September 1961, as shown by a letter he wrote to his step-grandson, a lawyer, on 29 September 1961 for advice concerning Bertie's arrest in the novel. In the letter, Wodehouse explains that Sir Watkyn Bassett, as a Justice of the Peace, has Bertie arrested for stealing something valuable of his and intends to give Bertie a sentence, but agrees not to press charges if Jeeves leaves Bertie's employ and comes to work for him. Wodehouse asked if a Justice of the Peace can try a man for stealing something from him, and whether or not a criminal is released if a complainant withdraws a charge after an arrest has been made.[10]

Publication history

Before being published as a novel, Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves was printed in the February and March 1963 issues of the magazine Playboy, illustrated by Bill Charmatz.[11]

Wodehouse dedicated the US edition of the novel: "To David Jasen".[1]

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves was included in the 1976 three novel collection Jeeves, Jeeves, Jeeves, along with Jeeves and the Tie That Binds and How Right You Are, Jeeves, published by Avon.[12]

Reception

- Richard Armour, The Los Angeles Times (7 April 1963): "What can one say about a new P. G. Wodehouse novel? Wodehouse fans need know only that it is in the bookstores, or, at most, that it is not quite so good, about the same, or better than the average Wodehouse. Those who have never read a Wodehouse novel, if there are any such, wouldn't understand, no matter how much they were told. Anyhow, this one is genuine Wodehouse, from the marmaladed slice of toast on the first page to the 'Thank you very much, sir' and the 'Not at all, Jeeves,' on the last. The plot revolves around (and around) Sir Watkyn's daughter Madeline, who has designs on Bertie Wooster, and Bertie Wooster, who has designs on remaining single. As usual again, it is Jeeves who rescues his master from a fate worse than death. Good old Bertie. Good old Jeeves".[13]

- The Times (22 August 1963): "Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves is Mr. P. G. Wodehouse's umpteenth book but, as he is impervious to those vacillations which are sometimes labelled as 'development' in other writers, it might as well be his first. Bertie Wooster continues to live in the timeless world of clubs and country houses and to avoid matrimony by the skin of his teeth. Jeeves is as unflappable as ever and the assorted bunch of squires and viscounts are suitably grotesque. Those who like Mr. Wodehouse's work will not be disappointed but it is unlikely to make him any new converts".[14]

Adaptations

Television

The story was adapted into the Jeeves and Wooster episode "Trouble at Totleigh Towers" which first aired on 13 June 1993.[15] There are some differences in plot, including:

- In the episode, the black amber statuette is widely believed to be cursed. There was no mention of a curse in the original story.

- In the episode, Bertie takes the statuette at night, and when he is caught by Sir Watkyn and Spode, Jeeves surreptitiously takes it from where Bertie is holding it behind his back. In the original story, Stiffy took the statuette and gave it to Bertie.

- Jeeves says the statuette originates from a group called the "Umgali" people in the episode, and that the Umgali chief has the right to reclaim the statue. The chief is busy watching racing at Ascot, however, so Bertie wears blackface and a tribal costume to pretend to be the chief to get rid of the statuette for Stiffy. He is thwarted when the real chief, Chief "Buffy" Toto, appears, though Toto purchases the statuette. None of this occurs in the original story.

- The local school treat, which Bertie does not attend in the original story, features more prominently in the episode. Many of the story's events, including Gussie and Emerald's engagement and Stinker gaining a vicarage, occur at the school treat in the episode.

- In the episode, Bertie doesn't go to jail, and in addition to giving up the Alpine hat, Bertie agrees to bring Jeeves to Havana for a month.

Radio

Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves was adapted for radio in 1980–1981 as part of the BBC series What Ho! Jeeves starring Michael Hordern as Jeeves and Richard Briers as Bertie Wooster.[16]

It was adapted as a two-part radio drama in 2018, with Martin Jarvis as Jeeves, James Callis as Bertie Wooster, Joanna Lumley as Aunt Dahlia, Adam Godley as Roderick Spode, Michael York as Major Plank, Ian Ogilvy as Sir Watkyn Bassett, Julian Sands as the Rev. Harold Pinker, Moira Quirk as Stiffy Byng, Elizabeth Knowelden as Madeline Bassett, Matthew Wolf as Gussie Fink-Nottle, Tara Lynne Barr as Emerald Stoker, and Kenneth Danziger as Cyril and Butterfield.[17]

References

- Notes

- 1 2 McIlvaine (1990), p. 97, A86.

- ↑ Wodehouse (2008) [1963], chapter 4, p. 36.

- ↑ Wodehouse (2008) [1963], chapter 11, p. 94.

- ↑ Thompson (1992), pp. 279–280.

- ↑ Thompson (!992), p. 291.

- ↑ Hall (1974), p. 112.

- ↑ Thompson (1992), pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Hall (1974), pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Thompson (!992), p. 103.

- ↑ Thompson (1992), p. 64, 359.

- ↑ Cawthorne (2013), p. 138.

- ↑ McIlvaine (1990), pp. 123-124, B18a.

- ↑ Armour, Richard (7 April 1963). "Fun With Wodehouse and Alexander King". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved 4 April 2008.

- ↑ "New Fiction". The Times. London. 22 August 1963. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ↑ "Jeeves and Wooster Series 4, Episode 5". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ "What Ho! Jeeves (Part 5)". BBC Genome Project. BBC. 2019. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- ↑ "Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves". BBC Radio 4. BBC. Retrieved 4 October 2019.

- Bibliography

- Cawthorne, Nigel (2013). A Brief Guide to Jeeves and Wooster. London: Constable & Robinson. ISBN 978-1-78033-824-8.

- Hall, Robert A. Jr. (1974). The Comic Style of P. G. Wodehouse. Hamden: Archon Books. ISBN 0-208-01409-8.

- McIlvaine, Eileen; Sherby, Louise S.; Heineman, James H. (1990). P. G. Wodehouse: A Comprehensive Bibliography and Checklist. New York: James H. Heineman Inc. ISBN 978-0-87008-125-5.

- Thompson, Kristin (1992). Wooster Proposes, Jeeves Disposes or Le Mot Juste. New York: James H. Heineman, Inc. ISBN 0-87008-139-X.

- Wodehouse, P. G. (2008) [1963]. Stiff Upper Lip, Jeeves (Reprinted ed.). London: Arrow Books. ISBN 978-0099513957.

External links

- The Russian Wodehouse Society's page, with a list of characters