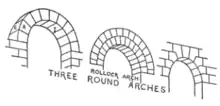

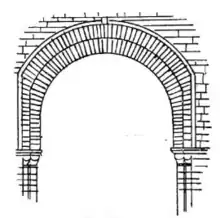

Semicircular arch is an arch with intrados (inner surface) shaped like a semicircle.[1][2] This type of arch was adopted and very widely used by the Romans, thus becoming permanently associated with the Roman architecture.[3] When the arch construction involves the Roman techniques (either wedge-like stone voussoirs or thin Roman bricks), it is known as a Roman arch.[4] The semicircular arch is also known as a round arch.[5][6]

The rise (height) of a round arch is limited to 1⁄2 of its span,[7] so it looks more "grounded" than a parabolic arch[3] or a pointed arch.[7] Whenever a higher semicircular arch was required (for example, for a narrow arch to match the height of a nearby broad one), either stilting or horseshoe shape were used, thus creating a stilted arch (also surmounted[8]) and horseshoe arch respectively.[9] These "shifts and dodges" were immediately dropped once the pointed arch with its malleable proportions was adopted.[7] Still, "the Romanesque arch is beautiful as an abstract line. Its type is always before us in that of the apparent vault of heaven, and horizon of the earth" (John Ruskin, "The Seven Lamps of Architecture").[10]

The popularity of the semicircular arch is based on simplicity of its layout and construction,[11] not superior structural properties. The sides of this arch swing wider than the perfect funicular shape and therefore experience a bending moment with the force directed outwards.[12] To prevent buckling, heavy surcharge (fill), so called spandrel, needs to be applied outside of the haunches.[11]

In addition to the Imperial Roman construction, round arches are also associated with Byzantine, Romanesque (and Neo-Romanesque), Renaissance[13] and Rundbogenstil styles. While the semicircular arch was known in the Greek architecture, it mostly played there a decorative, not structural, role.[14]

References

- ↑ Oxford University Press 2006a.

- ↑ Kurtz 2007, p. 34.

- 1 2 Sandaker, Eggen & Cruvellier 2019, p. 445.

- ↑ Oxford University Press 2006b.

- ↑ Oxford University Press 2006c.

- ↑ Sturgis & Davis 2013, p. 112.

- 1 2 3 Bond 1905, p. 265.

- ↑ "surmounted arch". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary.

- ↑ Bond 1905, p. 262.

- ↑ Bond 1905, p. 261.

- 1 2 Mark 1996, p. 387.

- ↑ Sandaker, Eggen & Cruvellier 2019, p. 464.

- ↑ Sturgis & Davis 2013, p. 115.

- ↑ DeLaine 1990, p. 412.

Sources

- "semicircular arch". A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2006a. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198606789.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- "Roman arch". A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2006b. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198606789.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- "round". A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture. Oxford University Press. 2006c. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198606789.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-860678-9.

- Sandaker, B.N.; Eggen, A.P.; Cruvellier, M.R. (2019). The Structural Basis of Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-22918-6. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- Sturgis, Russell; Davis, Francis A. (2013). "Round Arch". Sturgis' Illustrated Dictionary of Architecture and Building: An Unabridged Reprint of the 1901-2 Edition. Dover Architecture. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-14840-3. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- Bond, Francis (1905). Gothic Architecture in England: An Analysis of the Origin & Development of English Church Architecture from the Norman Conquest to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. Collections spéciales. B. T. Batsford. Retrieved 2023-12-15.

- DeLaine, Janet (1990). "Structural experimentation: The lintel arch, corbel and tie in western Roman architecture". World Archaeology. 21 (3): 407–424. doi:10.1080/00438243.1990.9980116. ISSN 0043-8243.

- Mark, Robert (July–August 1996). "Architecture and Evolution" (PDF). American Scientist. Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society. 84 (4): 383–389. JSTOR 29775710.

- Kurtz, J.P. (2007). Dictionary of Civil Engineering: English-French. EngineeringPro collection. Springer US. ISBN 978-0-306-48474-2. Retrieved 2024-01-01.

.jpg.webp)

_Hall_east_entrance_-_University_of_Portland.jpg.webp)