Stilts are poles, posts or pillars used to allow a structure or building to stand at a distance above the ground or water. In flood plains, and on beaches or unstable ground, buildings are often constructed on stilts to protect them from damage by water, waves or shifting soil or sand. As these issues were commonly faced by many societies around the world, stilts have become synonymous with various places and cultures, particularly in South East Asia and Venice.

Stilt house

Stilts are a common architectural element in tropical architecture, especially in Southeast Asia and South America, but can be found worldwide. Stilts also have a large prominence in Oceania and Europe as well as the Arctic, where the stilts elevate houses above the permafrost. The length of stilts may vary widely; stilts of traditional houses can be measured from half a meter to 5 or 6 meters. Stilt houses have been used for millennia, with evidence in the European Alps that stilt houses were constructed on a lake over 6000 years ago[1] and Herodotus making reference to stilt housing on lakes in Paeonia.[2] Settlements primarily composed of stilt housing are common in Micronesia and in Oceania.

Stilt homes in South America date back to Pre-Columbian times, with early explorers such as Vespucci noting the houses built on stilts by the local people whilst exploring, consequently giving the area the name Venezuela, or “Little Venice”. In the 18th Century, Jesuit João Daniel noted “Many nations live on lakes, or among them, where they have, over the water, their houses made of the same sort, only with the amend of being out of hay, that they erect with poles, and palm tree branches, and in them they live joyfully, like fish in the water” whilst travelling in the Brazilian Amazon Rainforest.[3] On the island of Chiloé, modern dwellers have incorporated stilts into house design due to local seismic activity causing tides up to 7 metres in height.[4]

Stilts were utilised by Inuit inhabiting the Bering Strait and Western Alaska, with stilts used to create level terraces for the community inhabiting Ugiuvak, also known as King Island. These stilt homes had a platform and a walrus skin roof and were built on up to 45 degree inclines, with the stilts largely constructed out of driftwood, due to the islands lack of forest cover. Many storehouses in the Bering Strait and nearby areas inhabited by the Yup’ik people on the mainland were constructed with driftwood stilts, a concept found in many regions around the world, usually to prevent pests from damaging food.[5]

There are many types and names of stilt housing, including:

- Diaojiaolou: Stilt houses built in Southern China

- Kelong: Fisherman homes in South East Asia

- Bahay Kubo: An integration of traditional Filipino stilt house with Colonial Spanish Architecture

- Sang Ghar: A style of stilt house built in the flood prone regions in the Assam state of India

- Palafito: A traditional South American stilt house style pre-dating Columbus

- Queenslander: A common building style in the flood-prone Queensland and northern New South Wales

Advantages

Many regions that utilise stilts in housing and architecture globally often face similar challenges to each other. Communities in tropical regions, wetlands, or other environments prone to high levels of moisture often utilise stilts to solve a particular issue facing an area.

One of the largest reasons stilts are used in vernacular architecture is to provide thermal comfort for inhabitants. For example, a study surveying the traditional stilt housing utilised by the Dong minority in Southern China, discovered that the airflow from elevating a house significantly cooled the house down.[6] Furthermore, the majority of people surveyed were satisfied with the natural cooling of their stilt homes in the hot, humid summer months as compared to people living in modern housing. Stilt housing also provides a large area to store commodities during non-flooding events, with many people using the bottom area to store livestock or items, or as entertainment areas.

Stilts are often used in buildings where there is a regular risk of flooding. Tropical regions can experience large quantities of rainfall in a small amount of time, often causing long and devastating floods for local people. The force of floodwaters often destroys buildings, meaning many people in flood communities build their houses on stilts such that they are well protected from high flood levels. Modelling of floodwaters acting on stilts and pillars in traditional and modern Thai stilts show that by using suitable simple construction methods, stilt houses can withstand large flooding events, protecting people and their possessions from being destroyed.[7]

Disadvantages

.jpg.webp)

Whilst the short term durability of stilt housing prevents consistent destruction,[7] the materials often used to make stilts can be damaged. This is due to materials becoming overstressed by flash flooding, where a large enough load is applied to the stilt that is large enough to cause deformation or damage, potentially causing structural failure or other serious damage to the building. Stilt homes which have been built using wooden pillars can rot due to general humidity or after being wet by flooding, compromising structural integrity.[8]

Despite providing cooling due to elevating, stilts can adversely affect the thermal efficiency of building, making it more expensive to heat/cool using technologies such as air-conditioning. A study on stilt houses in Chile found that traditional construction methods resulted in an average of 30.25% of heat losses in stilt houses came from the open floor, increasing the energy consumption of each home.[9]

A large social disadvantage of stilt housing is the difficulties faced by people with mobility issues.[7] The stairs leading up to the main floor may often be inaccessible to people with disabilities such as people who are in a wheelchair. While an elevator may be added, this is often an expensive investment and cannot be afforded by people in remote communities, or feasible with local issues such as regular flooding.

Construction materials and methods

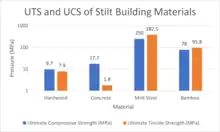

In traditional stilt houses, wood is a prevalent structural material used to manufacture the stilts. This is usually from a local lumber source, with many traditional stilt houses in Asia using bamboo for structural support.[8] In modern homes, concrete and steel are often used as construction material for the structural stilts in houses.

In the Avieiras stilt houses along the Tagus River in Portugal, canes growing by the riverbank and trunks of large trees were used as stilts to support the homes of local fisherman.[10] Over time, concrete slabs have been added to support the wood and extend the pillars foundation into the ground, making buildings more stable in the case of flooding.[11]

Over the years many cultures have modified aspects of their construction method to improve the stability and strength of buildings on stilts. In Sumatra, severe damage from flooding and other natural disasters has modernised many aspects of stilt house construction, with concrete being added to foundations of some buildings more prone to such events such as flooding, earthquakes, and large storms. By using concrete slabs in construction as well as by using concrete pillars, the stilts supporting the main building on top have been less damaged by recent events as compared to previous years. The improvement of technologies such as the durability of nails and screws has also made the connections between the pillar and various beams stronger.

Often the materials used in stilt housing reflect the challenges of its location. For example, a building with foundations underwater for most of the time often uses wood or reinforced concrete as the main material for stilts. A building that is sat on ground that is only flood-prone however can have brick and mortar as the primary structural element. Another type of stilts involves wooden stilts with ballasts to allow for a building to float freely in water. This can allow for a large amount of water to enter an area with the buildings safely afloat, reducing damage to a building during flooding events or from waves, winds, or tides. These stilts must be designed to provide the floating building with stability and buoyancy. This construction technique of developing a floating village is seen globally, from Peru to Hong Kong. Some floating villages in Vietnam are composed of a raft fixed to wooden stilts that are driven into the shallow sea floor. These stilts are periodically replaced every 30 years.[12]

In Indonesia, there are a variety of construction methods used in stilt houses. Foundations used for stilts include concrete pedestals or piles, with joints being fixed using screws/nails or being detachable interlocking wooden joints. A mix of continued pillars, where two pillars are connected directly vertically, or discontinued pillars, where a plate is placed in between the two pillars are used depending on local constraints. This durable building style has allowed some silt dwellings to surpass 100 years in age.[13]

Whilst fleeing the barbarians pillaging the Italian Peninsula in the 6th Century,[14] Roman farmers built elevated huts on wooden stilts on and surrounding the islands in the Venetian Lagoon. Over time as Venetian power and the local population grew, the city expanded, and the foundations of the city were required to be stronger and more durable. As such, the Venetians utilised approximately 18 metre long (60 feet) wooden poles manufactured from oak, larch or pine from local forests driven to use as the foundations of the city.[15] These stilts were driven deep into the ground through the unstable silt and dirt and into the hard clay beneath, allowing for a strong and stable structure. While wood is susceptible to rot and decay, the lack of dissolved oxygen in the mud protects the wood from significant rot, with some wooden Venetian foundations being over 500 years old. The disadvantage of using this system is that industrial action in the city often causes the city to sink at an increased rate.[16] For example, artisan wells constructed in the 1960s were originally drilled to get the city a reliable supply of fresh drinking water, as the water in the lagoon is entirely salt water. However, as water was pumped from the wells, Venice began to sink faster, leading to a ban on wells in the city due to the sensitivity of the foundations to surrounding construction.

Cultural aspects

Architecture and housing play an integral role in a culture, allowing for artistic expression in day-to-day life.

Dong culture

The Dong minority in the Guangxi province of China decorate all aspects of their homes, including the pillars that support the house.[6] With modern construction using concrete instead of wood, many locals create a façade to ensure the style of housing remains consistent with the traditional style that defines the local culture. The area between the first floor and ground is often used to store livestock.

Thai culture

Stilts have been embedded into Thai architectural culture, with stilt housing making up a significant proportion of the country's housing in agricultural regions such as the Uttaradit and Phetchabun region.[7] Many buildings, even away from areas prone to flooding often incorporate stilts into their design, such as temples. Due to the prominence of such buildings in Thailand, the architecture there is often associated with stilts.

Indonesian culture

In Indonesia, the construction of the house symbolizes the division of the macrocosm into three regions: the upper world; the seat of deities and ancestors, the middle world; the realm of human, and lower world; the realm of demon and malevolent spirit. The typical way of buildings in Southeast Asia is to build on stilts, an architectural form usually combined with a saddle roof.[17]

The usage of stilts in homes in Indonesia has been dated back hundreds of years.[11] Many styles of vernacular buildings have been developed depending on the needs of the people and dynamics of the environment. Recent disasters such as tsunamis and flooding in the Teunom region of Sumatra have forced the modernisation of building materials and methods, with concrete replacing the wooden foundations of many houses. The area at the bottom of the building, referred to as the stage area, is often used aesthetically with fruits and flowers being commonplace in the space.

Stilts can be found in Indonesian vernacular architecture such as Dayak long houses,[17] Torajan Tongkonan, Minangkabau Rumah Gadang, and Malay houses. The construction is known locally as Rumah Panggung (lit: "stage house") houses built on stilts. This was to avoid wild animals and floods, to deter thieves, and for added ventilation. In Sumatra, traditionally stilted houses are designed in order to avoid dangerous wild animals, such as snakes and tigers. While in areas located close to big rivers of Sumatra and Borneo, the stilts help to elevated house above flood surface.

Portuguese culture

The development of the Avieira architecture along the Tagus River in Portugal[10] occurred from seasonal migration. Cold winters meant fishermen would fish in rivers instead of the ocean, developing communities along the shoreline. Painting the exterior, including the stilts, usually green, red, blue, or orange gave individual expression to the fisherman who usually made the houses themselves.

See also

References

- ↑ "7000-year-old grain reveals the origin of the Swiss stilt houses". archaeology-world.com. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ↑ Herodotus (1987). The History. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 5.16. ISBN 0226327701.

- ↑ Navarro, Alexandre Guida (2019). "Pile Dwellings or Stilt Houses in Prehistory of Brazil". Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology: 1–12. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3202-1. ISBN 978-3-319-51726-1.

- ↑ Pareti, Stefania; Flores, David; Rudolph, Loreto; Valdebenito, Vicente (April 2022). "Wooden Vernacular Architecture as a Sustainable Development and Security Mechanism. The case of the Palafitos of Chiloé, Chile". Proceedings of the 7th World Congress on Civil, Structural, and Environmental Engineering. doi:10.11159/icgre22.223. ISBN 978-1-927877-99-9. S2CID 248466760.

- ↑ Alix, Claire (23 May 2013). "Using wood on King Island, Alaska". Études/Inuit/Studies. 36 (1): 89–112. doi:10.7202/1015955ar.

- 1 2 Jin, Yue; Zhang, Ning (January 2021). "Comprehensive Assessment of Thermal Comfort and Indoor Environment of Traditional Historic Stilt House, a Case of Dong Minority Dwelling, China". Sustainability. 13 (17): 9966. doi:10.3390/su13179966.

- 1 2 3 4 Charoenchai, Olarn; Bhaktikul, Kampanad (1 January 2020). "Structural Durability Assessment of Stilt Houses to Flash Flooding: Case Study of Flash Flood-Affected Sites in Thailand". Environment and Natural Resources Journal. 18 (1): 85–100. doi:10.32526/ennrj.18.1.2020.09. S2CID 213987429.

- 1 2 Liu, Z. (2019). New Possibilities for Stilt Building (M.Arch). Rochester Institute of Technology, Golisano Institute for Sustainability. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ↑ Manriquez, Carla; Sills, Pablo (26 August 2019). "Evaluation of the energy performance of stilt houses (palafitos) of the Chiloé Island. The role of dynamic thermal simulation on heritage architecture". Simulation - VIRTUAL AND AUGMENTED REALITY. 3 (2). Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- 1 2 Virtudes, Ana; Almeida, Filipa. "THE TERRITORY OF "AVIEIRAS" STILT-HOUSE VILLAGES IN THE SURVEY ON VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE: WHAT DOES THE FUTURE HOLD?" (PDF). Comum. Cooperativa de Ensino Superior Artístico do Porto. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- 1 2 Nursaniah, C., Machdar, I., Azmeri, Munir, A., Irwansyah, M., & Sawab, H. (2019). "Transformation of stilt houses: a way to respond to the environment to be sustainable". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. IOP Publishing Ltd. 365 (1): 012017. Bibcode:2019E&ES..365a2017N. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/365/1/012017. S2CID 210607461.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Susanto, D; Lubis, M S (March 2018). "Floating houses "lanting" in Sintang: Assessment on sustainable building materials". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 126 (1): 012135. Bibcode:2018E&ES..126a2135S. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/126/1/012135. S2CID 169081828.

- ↑ Nyssa, A.; Susanto, D.; Panjaitan, T. (2022). Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering (201 ed.). Virtual, Online: Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH. pp. 625–632. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-6932-3_54. ISBN 9789811669316. S2CID 246458642. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ↑ Howard, Deborah (2002). The architectural history of Venice (Unspecified ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 1–9. ISBN 0300090293.

- ↑ "VENICE FOUNDATIONS: HOW VENICE WAS BUILT?". Venice by Venetians. 7 April 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- ↑ Tate, Bria; Olivares, Jose; Vogt, Alfred. "Engineering Venice". sites.google.com. Retrieved 26 May 2022.

- 1 2 "Traditional Houses". Art Asia. Retrieved 17 May 2012.